Identifying and Developing the Personal Voice in Improvised Music Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ronnie Scott's Jazz C

GIVE SOMEONE THE GIFT OF JAZZ THIS CHRISTMAS b u l C 6 z 1 0 z 2 a r J e MEMBERSHIP TO b s ’ m t t e c o e c D / S r e e i GO TO: WWW.RONNIESCOTTS.CO.UK b n m e OR CALL: 020 74390747 n v o Europe’s Premier Jazz Club in the heart of Soho, London ‘Hugh Masekela Returns...‘ o N R Cover artist: Hugh Masekela Page 36 Page 01 Artists at a Glance Tues 1st - Thurs 3rd: Steve Cropper Band N Fri 4th: Randy Brecker & Balaio play Randy In Brasil o v Sat 5th: Terence Blanchard E-Collective e Sun 6th Lunch Jazz: Atila - ‘King For A Day’ m b Sun 6th: Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Orchestra e Mon 7th - Sat 12th: Kurt Elling Quintet “The Beautiful Day” r Thurs 10th: Late Late Show Special: Brandee Younger: A Tribute To Alice Coltrane & Dorothy Ashby Sun 13th Lunch Jazz: Salena Jones & The Geoff Eales Quartet Sun 13th: Dean Brown - Rolajafufu The Home Secretary Amber Rudd came up with Mon 14th - Tues 15th : Bettye LaVette Wed 16th - Thurs 17th : Marcus Strickland Twi-Life a wheeze the other day that all companies should Fri 18th - Sat 19th : Charlie Hunter: An Evening With publish how many overseas workers they employ. Sun 20th Lunch Jazz: Charlie Parker On Dial: Presented By Alex Webb I, in my naivety, assumed this was to show how Sun 20th: Oz Noy Mon 21st: Ronnie Scott’s Blues Explosion much we relied upon them in the UK and that a UT Tues 22nd - Wed 23rd: Hugh Masekela SOLD O dumb-ass ban or regulated immigration system An additional side effect of Brexit is that we now Thurs 24th - Sat 26th: Alice Russell would be highly harmful to the economy as a have a low strength pound against the dollar, Sun 27th Lunch Jazz: Pete Horsfall Quartet whole. -

CHARLIE PARKER Di Leonard Feather

CHARLIE PARKER di Leonard Feather E stato come un ciclone che ha attraversato la storia del jazz, un'esplosione solitaria e geniale, che ha cambiato il corso della musica afroamericana, come era accaduto in precedenza soltanto con Armstrong. Da ogni punto di vista tonale, melodico, armonico la sua musica ha aperto una strada nuova non solo per i sassofonisti, ma anche per tutti i jazz men moderni, qualunque fosse il loro strumento. Ha detto Lennie Tristano, dopo la sua morte: "Se Parker avesse voluto invocare le leggi che puniscono il plagio, avrebbe potuto accusare praticamente tutti coloro che hanno inciso un disco negli ultimi dieci anni". La sua parabola artistica e la sua tormentata biografia, indissolubilmente legate, sono diventate ben presto leggenda, una leggenda tragica, quella dell'arte che raggiunge le vette del sublime attraverso la dannazione, come è accaduto per Poe, Van Gogh, Verlaine e tanti altri artisti "maledetti".Sui muri delle stazioni della metropolitana newyorkese, su quelli delle case del Village, sulle pareti dei jazz club, i suoi ammiratori scrissero "Bird lives!", Parker è ancora vivo. E quel mistico messaggio è ancora oggi attuale. Perché il jazz non avrebbe compiuto i suoi passi da gigante senza il gesto visionario e disperato di Charlie "Bird" Parker. Charlie Parker nacque il 29 agosto del 1920 nella città sobborgo di Kansas City, nel Kansas. La madre Addie a cui "Bird" fu sempre mollo legato, aveva fatto la cameriera per molti anni, finché era riuscita a diventare infermiera in un ospedale. Il padre, che aveva lavorato con delle mediocri compagnie di vaudeville, era un fallito che amava rifugiarsi nella bottiglia. -

Hermann NAEHRING: Wlodzimierz NAHORNY: NAIMA: Mari

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ Hermann NAEHRING: "Großstadtkinder" Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; Stefan Dohanetz -d; Henry Osterloh -tymp; recorded 1985 in Berlin 24817 SCHLAGZEILEN 6.37 Amiga 856138 Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; Stefan Dohanetz -d; recorded 1985 in Berlin 24818 SOUJA 7.02 --- Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; Volker Schlott -fl; recorded 1985 in Berlin A) Orangenflip B) Pink-Punk Frosch ist krank C) Crash 24819 GROSSSTADTKINDER ((Orangenflip / Pink-Punk, Frosch ist krank / Crash)) 11.34 --- Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; recorded 1985 in Berlin 24820 PHRYGIA 7.35 --- 24821 RIMBANA 4.05 --- 24822 CLIFFORD 2.53 --- ------------------------------------------ Wlodzimierz NAHORNY: "Heart" Wlodzimierz Nahorny -as,p; Jacek Ostaszewski -b; Sergiusz Perkowski -d; recorded November 1967 in Warsaw 34847 BALLAD OF TWO HEARTS 2.45 Muza XL-0452 34848 A MONTH OF GOODWILL 7.03 --- 34849 MUNIAK'S HEART 5.48 --- 34850 LEAKS 4.30 --- 34851 AT THE CASHIER 4.55 --- 34852 IT DEPENDS FOR WHOM 4.57 --- 34853 A PEDANT'S LETTER 5.00 --- 34854 ON A HIGH PEAK -

Sydney Conservatorium of Music Postgraduate Handbook

2008 Postgraduate handbook Sydney Conservatorium of Music Postgraduate handbook Set a course for Handbooks online … visit www.usyd.edu.au/handbooks Acknowledgements Acknowledgements The Arms of the University Sidere mens eadem mutato Though the constellation may change the spirit remains the same Copyright Disclaimers This work is copyright. No material anywhere in this work may be 1. The material in this handbook may contain references to persons copied, reproduced or further disseminated ± unless for private use who are deceased. or study ± without the express and written permission of the legal 2. The information in this handbook was as accurate as possible at holder of that copyright. The information in this handbook is not to be the time of printing. The University reserves the right to make used for commercial purposes. changes to the information in this handbook, including prerequisites for units of study, as appropriate. Students should Official course information check with faculties for current, detailed information regarding Faculty handbooks and their respective online updates along with the units of study. University of Sydney Calendar form the official legal source of Price information relating to study at the University of Sydney. Please refer to the following websites: The price of this handbook can be found on the back cover and is in www.usyd.edu.au/handbooks Australian dollars. The price includes GST. www.usyd.edu.au/calendar Handbook purchases Amendments You can purchase handbooks at the Student Centre, or online at -

Trevor Tolley Jazz Recording Collection

TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to collection ii Note on organization of 78rpm records iii Listing of recordings Tolley Collection 10 inch 78 rpm records 1 Tolley Collection 10 inch 33 rpm records 43 Tolley Collection 12 inch 78 rpm records 50 Tolley Collection 12 inch 33rpm LP records 54 Tolley Collection 7 inch 45 and 33rpm records 107 Tolley Collection 16 inch Radio Transcriptions 118 Tolley Collection Jazz CDs 119 Tolley Collection Test Pressings 139 Tolley Collection Non-Jazz LPs 142 TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION Trevor Tolley was a former Carleton professor of English and Dean of the Faculty of Arts from 1969 to 1974. He was also a serious jazz enthusiast and collector. Tolley has graciously bequeathed his entire collection of jazz records to Carleton University for faculty and students to appreciate and enjoy. The recordings represent 75 years of collecting, spanning the earliest jazz recordings to albums released in the 1970s. Born in Birmingham, England in 1927, his love for jazz began at the age of fourteen and from the age of seventeen he was publishing in many leading periodicals on the subject, such as Discography, Pickup, Jazz Monthly, The IAJRC Journal and Canada’s popular jazz magazine Coda. As well as having written various books on British poetry, he has also written two books on jazz: Discographical Essays (2009) and Codas: To a Life with Jazz (2013). Tolley was also president of the Montreal Vintage Music Society which also included Jacques Emond, whose vinyl collection is also housed in the Audio-Visual Resource Centre. -

David Liebman Papers and Sound Recordings BCA-041 Finding Aid Prepared by Amanda Axel

David Liebman papers and sound recordings BCA-041 Finding aid prepared by Amanda Axel This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit November 30, 2018 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Berklee Archives Berklee College of Music 1140 Boylston St Boston, MA, 02215 617-747-8001 David Liebman papers and sound recordings BCA-041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement note...........................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 Scores and Charts................................................................................................................................... -

João Gilberto

SEPTEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 9 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

New World NW 271 Jazz Historians Explain the Coming of Bebop—The Radically New Jazz Style That Established Itself Toward

Bebop New World NW 271 Jazz historians explain the coming of bebop—the radically new jazz style that established itself toward the end of World War II—as a revolutionary phenomenon. The motives ascribed to the young pioneers in the style range from dissatisfaction with the restrictions on freedom of expression imposed by the then dominant big-band swing style to the deliberate invention of a subtle and mystifying manner of playing that could not be copied by uninitiated musicians. It has even been suggested that bebop was invented by black musicians to prevent whites from stealing their music, as had been the case with earlier jazz styles. Yet when Dizzy Gillespie, one of the two chief architects of the new style, was asked some thirty years after the fact if he had been a conscious revolutionary when bebop began, his answer was Not necessarily revolutionary, but evolutionary. We didn't know what it was going to evolve into, but we knew we had something that was a little different. We were aware of the fact that we had a new concept of the music, if by no other means than the enmity of the [older] musicians who didn't want to go through a change.... But it wasn't the idea of trying to revolutionize, but only trying to see yourself, to get within yourself. And if somebody copied it, okay! Were he able, the other great seminal figure of bebop, alto saxophonist Charlie Parker, would probably amplify Gillespie's opinion that the new music arose from inner needs rather than external factors. -

The Australian Music Centre Website

A select guide to Australian music theatre In Repertoire 2 I Dear Reader This guide takes you on a journey through contemporary Australian music theatre works that are currently available for touring. These and additional works in repertoire can all be found in the data base on pages 24 - 25 with contact addresses and other information. A few significant works no longer in repertoire are mentioned in the overview essay on pages 22-23. Many more are documented in Arias, Recent Australian Music Theatre (Red House Editions, 1997). A sample listing of works in progress is reported on page 26. On the same page a basic set of references can be found. A longer list is available on the Australian Music Centre website http://www.amcoz.com.au/amc The Editor Editor Keith Gallasch Assistant Editors Kirsten Krauth, Virginia Baxter Design i2i design, Sydney Cover photographs Left Arena Theatre Company, Eat Your Young, photo Jeff Busby Right Top Melbourne International Festival of the Arts, The Ghost Wife, photo Jeff Busby Right Bottom Queensland Theatre Company, The Sunshine Club, photo Rob MacColl All other photography credits page 27 Produced by RealTime for the Australia Council, the Federal Government’s arts funding and advisory body Australia Council PO Box 788 Strawberry Hills NSW Australia 2012 61 2 9215 9000 fax 61 2 9215 9111 [email protected] http://www.ozco.gov.au RealTime PO Box A2246 Sydney South NSW, Australia 1235 61 2 9283 2723 fax 61 2 9283 2724 [email protected] http://www.rtimearts.com.au/~opencity/ February 2000 ISBN 0 642 47222 X With the assistance of the Australian Music Centre 3 music theatre opera music+installation+performance Introduction The remarkable growth of Australian music theatre as we enter the new millennium appears to be exponential, manifesting itself in many different and surprising ways - as chamber opera, as the musical, as installation or site specific performance, and as pervasive musical scores and sound design in an increasing number of plays. -

CHARLIE PARKER Saxophonist, Composer

DESSINS ALAIN GARRIGUE, SCÉNARIO CHRISTIAN BONNET INSPIRÉ DE LA BIOGRAPHIE DE CHARLIE PARKER Du même auteur : – Séjour en Afrique (Scèn. J.L. Coudray - Ed. Rackham ) 1989 (Alf-Art Coup de Cœur 1990 Angoulème) ; – Le destin perdu d’Argentino Diaz (Ed. Delcourt) 1990 ; – Le cirque de Dieu (Ed. Delcourt) 1991 ; – Samizdat (Ed. Delcourt) 1992 ; – Le sacrifi ce Fong (Ed. Delcourt) 1994 ; – Le réveil des Nations (Ed. Autrement) Collectif - 1996 ; – Hitchcock présente : Pas de pitié pour le mouchard (Ed. Vents d’Ouest) Collectif - 1996 ; – Le montreur de Fantasmes (Ed. Paquet) 1999 ; – A Frounz (Ed. Le Studio) 1999 ; – Le Poulpe : Le saint des seins (Scèn. G. Nicloux - Ed. 6 Pieds Sous Terre) 2000 ; – Scott Joplin (Ed. BDMUSIC) 2005. 20 BIOGRAPHIE CHARLIE PARKER 24 BIOGRAPHY CHARLIE PARKER 27 DISCOGRAPHIE CD1 CHARLIE PARKER (1945–1951) 28 DISCOGRAPHIE CD2 CHARLIE PARKER (1947–1952) BDJAZZ EST UNE COLLECTION DES ÉDITIONS BDMUSIC / DIRECTEUR DE LA COLLECTION BRUNO THÉOL / SÉLECTION & TEXTES CHRISTIAN BONNET & CLAUDE CARRIÈRE / TRANSLATION MARTIN DAVIES / TRANSFERTS & MASTERING CHRISTOPHE HÉNAULT & ALEXIS FRENKEL / STUDIO ART & SON PARIS / DESIGN GRAPHIQUE RENAUD BARÈS BDJZ009 (P) & (C) 2011 BDJAZZ PARIS – www.bdmusic.fr ACHEVÉ D’IMPRIMER EN SEPTEMBRE 2011. TOUS DROITS DE TRADUCTION, DE REPRODUCTION ET D’ADAPTATION STRICTEMENT RÉSERVÉS POUR TOUT PAYS. TOUTE REPRODUCTION, MÊME PARTIELLE DE CET OUVRAGE EST INTERDITE. TOUTE COPIE OU REPRODUCTION EST UNE CONTREFAÇON PASSIBLE DES PEINES PRÉVUES PAR LA LOI DU 11 MARS 1957 SUR LA PROTECTION DES DROITS D’AUTEUR. DÉPÔT LÉGAL OCTOBRE 2011 / ISBN 2-84907-009-2. 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 BIOGRAPHIE CHARLIE PARKER saxophoniste, compositeur Charlie Christopher Parker naît le 29 août 1920 à Kansas City, Kansas, États-Unis. -

Blues, Rhythm Changes, Coltrane Changes

LearnMusicTheory.net 4.4.1 Standard Changes: Blues, Rhythm, Coltrane • Changes = a standard chord progression that can be transposed to any key • Three of the most common progressions are blues changes, rhythm changes, and Coltrane changes. Blues changes • The blues is a 12-bar (12-measure) form, organized as 3 stanzas of 4 measures each. • In the most basic version, each measure uses only one chord. • The most basic form is: stanza 1= I - I - I - I, stanza 2= IV-IV-I-I, and stanza 3=V-IV-I-I • An example in C major would be: C-C-C-C, F-F-C-C, G-F-C-C (each chord symbol is 1 measure) • Substitutions and reharmonizations have resulted in a huge number of variant forms (ex: I7 - I7 - I7 etc.) Rhythm Changes • Rhythm changes are based on the chord progression from “I Got Rhythm” by George Gershwin. • Jazz musicians (especially Bebop musicians) created many new tunes (called contrafacts) with the chords. • Rhythm changes are 32 measures long, organized as 4 sections of 8 measures each, in the pattern AABA. • The chord progression for each A section is: I vi / ii V / I vi / ii V / I I7 / IV #iv°7 (or iv) / I V / I • The chord progression for the B section (called the “Bridge”) is: III7 / III7 / VI7 / VI7 / II7 / II7 / V7 / V7 • The chords in the B section could also be analyzed as a circle-of-fifths sequence of secondary dominants. • The most basic version has few 7th chords in the A section, but many variants include 7ths/9ths/11ths/13ths, etc. -

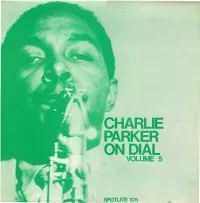

Charlie Parker on Dial Volume 5

ON KLACT-OVEESEDS-TENE VOlis one of Charlie Parker's most Bird turns these famous jazzmen around with his so TheCHARLIE reissue of Charlie Parker's historicalPARKER recording sessions for Dial Records continues on Spotlite Volume 5 with the fascinating and original compositions. The stirring, march-like reconstructionAH. complete chronological sequence of the November 4, 1947 introduction is a Parker creation, although some reviewers date at WOR Studios, Thirty-Ninth Street and Broadway, accused Bird of plagiarism when the record first appeared, The r.construction of the final Parker date for Dial Records New York City. This session took place early Tuesday because the same figure had been used as the theme on THE at WOR, Wednesday, December 17, 1947 will appear on evening and was supervised by Ross Russell, president and CHASE by Dexter Gordon and Wardell Gray, recorded for Spotlite 106. director of artists and repertoire for Dial Records. The Dial in Hollywood, June 12, 1947. Actually the tenor recording engineer, as with all Dial sessions in New York, was saxophonists had picked Bird's brains at a jam session on Doug Hawkins, who combined a license as an acoustical Central Avenue in Los Angeles earlier that year and, engineer with a music degree from Juilliard School of Music. remembering the strange and effective figure, and being stuck PERSONNEL for a theme for their saxophone duel, had fallen back on The personnel of the Charlie Parker Quintet—Parker, Miles Charlie s material. It was Charlie's all along and may have Davis, Duke Jordan, Tommy Potter and Max Roach—was the been first played by him much earlier than 1947.