An Approach to Phrase Rhythm in Jazz1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ronnie Scott's Jazz C

GIVE SOMEONE THE GIFT OF JAZZ THIS CHRISTMAS b u l C 6 z 1 0 z 2 a r J e MEMBERSHIP TO b s ’ m t t e c o e c D / S r e e i GO TO: WWW.RONNIESCOTTS.CO.UK b n m e OR CALL: 020 74390747 n v o Europe’s Premier Jazz Club in the heart of Soho, London ‘Hugh Masekela Returns...‘ o N R Cover artist: Hugh Masekela Page 36 Page 01 Artists at a Glance Tues 1st - Thurs 3rd: Steve Cropper Band N Fri 4th: Randy Brecker & Balaio play Randy In Brasil o v Sat 5th: Terence Blanchard E-Collective e Sun 6th Lunch Jazz: Atila - ‘King For A Day’ m b Sun 6th: Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Orchestra e Mon 7th - Sat 12th: Kurt Elling Quintet “The Beautiful Day” r Thurs 10th: Late Late Show Special: Brandee Younger: A Tribute To Alice Coltrane & Dorothy Ashby Sun 13th Lunch Jazz: Salena Jones & The Geoff Eales Quartet Sun 13th: Dean Brown - Rolajafufu The Home Secretary Amber Rudd came up with Mon 14th - Tues 15th : Bettye LaVette Wed 16th - Thurs 17th : Marcus Strickland Twi-Life a wheeze the other day that all companies should Fri 18th - Sat 19th : Charlie Hunter: An Evening With publish how many overseas workers they employ. Sun 20th Lunch Jazz: Charlie Parker On Dial: Presented By Alex Webb I, in my naivety, assumed this was to show how Sun 20th: Oz Noy Mon 21st: Ronnie Scott’s Blues Explosion much we relied upon them in the UK and that a UT Tues 22nd - Wed 23rd: Hugh Masekela SOLD O dumb-ass ban or regulated immigration system An additional side effect of Brexit is that we now Thurs 24th - Sat 26th: Alice Russell would be highly harmful to the economy as a have a low strength pound against the dollar, Sun 27th Lunch Jazz: Pete Horsfall Quartet whole. -

CHARLIE PARKER Di Leonard Feather

CHARLIE PARKER di Leonard Feather E stato come un ciclone che ha attraversato la storia del jazz, un'esplosione solitaria e geniale, che ha cambiato il corso della musica afroamericana, come era accaduto in precedenza soltanto con Armstrong. Da ogni punto di vista tonale, melodico, armonico la sua musica ha aperto una strada nuova non solo per i sassofonisti, ma anche per tutti i jazz men moderni, qualunque fosse il loro strumento. Ha detto Lennie Tristano, dopo la sua morte: "Se Parker avesse voluto invocare le leggi che puniscono il plagio, avrebbe potuto accusare praticamente tutti coloro che hanno inciso un disco negli ultimi dieci anni". La sua parabola artistica e la sua tormentata biografia, indissolubilmente legate, sono diventate ben presto leggenda, una leggenda tragica, quella dell'arte che raggiunge le vette del sublime attraverso la dannazione, come è accaduto per Poe, Van Gogh, Verlaine e tanti altri artisti "maledetti".Sui muri delle stazioni della metropolitana newyorkese, su quelli delle case del Village, sulle pareti dei jazz club, i suoi ammiratori scrissero "Bird lives!", Parker è ancora vivo. E quel mistico messaggio è ancora oggi attuale. Perché il jazz non avrebbe compiuto i suoi passi da gigante senza il gesto visionario e disperato di Charlie "Bird" Parker. Charlie Parker nacque il 29 agosto del 1920 nella città sobborgo di Kansas City, nel Kansas. La madre Addie a cui "Bird" fu sempre mollo legato, aveva fatto la cameriera per molti anni, finché era riuscita a diventare infermiera in un ospedale. Il padre, che aveva lavorato con delle mediocri compagnie di vaudeville, era un fallito che amava rifugiarsi nella bottiglia. -

Hermann NAEHRING: Wlodzimierz NAHORNY: NAIMA: Mari

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ Hermann NAEHRING: "Großstadtkinder" Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; Stefan Dohanetz -d; Henry Osterloh -tymp; recorded 1985 in Berlin 24817 SCHLAGZEILEN 6.37 Amiga 856138 Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; Stefan Dohanetz -d; recorded 1985 in Berlin 24818 SOUJA 7.02 --- Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; Volker Schlott -fl; recorded 1985 in Berlin A) Orangenflip B) Pink-Punk Frosch ist krank C) Crash 24819 GROSSSTADTKINDER ((Orangenflip / Pink-Punk, Frosch ist krank / Crash)) 11.34 --- Hermann Naehring -perc,marimba,vib; Dietrich Petzold -v; Jens Naumilkat -c; Wolfgang Musick -b; Jannis Sotos -g,bouzouki; recorded 1985 in Berlin 24820 PHRYGIA 7.35 --- 24821 RIMBANA 4.05 --- 24822 CLIFFORD 2.53 --- ------------------------------------------ Wlodzimierz NAHORNY: "Heart" Wlodzimierz Nahorny -as,p; Jacek Ostaszewski -b; Sergiusz Perkowski -d; recorded November 1967 in Warsaw 34847 BALLAD OF TWO HEARTS 2.45 Muza XL-0452 34848 A MONTH OF GOODWILL 7.03 --- 34849 MUNIAK'S HEART 5.48 --- 34850 LEAKS 4.30 --- 34851 AT THE CASHIER 4.55 --- 34852 IT DEPENDS FOR WHOM 4.57 --- 34853 A PEDANT'S LETTER 5.00 --- 34854 ON A HIGH PEAK -

Trevor Tolley Jazz Recording Collection

TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to collection ii Note on organization of 78rpm records iii Listing of recordings Tolley Collection 10 inch 78 rpm records 1 Tolley Collection 10 inch 33 rpm records 43 Tolley Collection 12 inch 78 rpm records 50 Tolley Collection 12 inch 33rpm LP records 54 Tolley Collection 7 inch 45 and 33rpm records 107 Tolley Collection 16 inch Radio Transcriptions 118 Tolley Collection Jazz CDs 119 Tolley Collection Test Pressings 139 Tolley Collection Non-Jazz LPs 142 TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION Trevor Tolley was a former Carleton professor of English and Dean of the Faculty of Arts from 1969 to 1974. He was also a serious jazz enthusiast and collector. Tolley has graciously bequeathed his entire collection of jazz records to Carleton University for faculty and students to appreciate and enjoy. The recordings represent 75 years of collecting, spanning the earliest jazz recordings to albums released in the 1970s. Born in Birmingham, England in 1927, his love for jazz began at the age of fourteen and from the age of seventeen he was publishing in many leading periodicals on the subject, such as Discography, Pickup, Jazz Monthly, The IAJRC Journal and Canada’s popular jazz magazine Coda. As well as having written various books on British poetry, he has also written two books on jazz: Discographical Essays (2009) and Codas: To a Life with Jazz (2013). Tolley was also president of the Montreal Vintage Music Society which also included Jacques Emond, whose vinyl collection is also housed in the Audio-Visual Resource Centre. -

New World NW 271 Jazz Historians Explain the Coming of Bebop—The Radically New Jazz Style That Established Itself Toward

Bebop New World NW 271 Jazz historians explain the coming of bebop—the radically new jazz style that established itself toward the end of World War II—as a revolutionary phenomenon. The motives ascribed to the young pioneers in the style range from dissatisfaction with the restrictions on freedom of expression imposed by the then dominant big-band swing style to the deliberate invention of a subtle and mystifying manner of playing that could not be copied by uninitiated musicians. It has even been suggested that bebop was invented by black musicians to prevent whites from stealing their music, as had been the case with earlier jazz styles. Yet when Dizzy Gillespie, one of the two chief architects of the new style, was asked some thirty years after the fact if he had been a conscious revolutionary when bebop began, his answer was Not necessarily revolutionary, but evolutionary. We didn't know what it was going to evolve into, but we knew we had something that was a little different. We were aware of the fact that we had a new concept of the music, if by no other means than the enmity of the [older] musicians who didn't want to go through a change.... But it wasn't the idea of trying to revolutionize, but only trying to see yourself, to get within yourself. And if somebody copied it, okay! Were he able, the other great seminal figure of bebop, alto saxophonist Charlie Parker, would probably amplify Gillespie's opinion that the new music arose from inner needs rather than external factors. -

CHARLIE PARKER Saxophonist, Composer

DESSINS ALAIN GARRIGUE, SCÉNARIO CHRISTIAN BONNET INSPIRÉ DE LA BIOGRAPHIE DE CHARLIE PARKER Du même auteur : – Séjour en Afrique (Scèn. J.L. Coudray - Ed. Rackham ) 1989 (Alf-Art Coup de Cœur 1990 Angoulème) ; – Le destin perdu d’Argentino Diaz (Ed. Delcourt) 1990 ; – Le cirque de Dieu (Ed. Delcourt) 1991 ; – Samizdat (Ed. Delcourt) 1992 ; – Le sacrifi ce Fong (Ed. Delcourt) 1994 ; – Le réveil des Nations (Ed. Autrement) Collectif - 1996 ; – Hitchcock présente : Pas de pitié pour le mouchard (Ed. Vents d’Ouest) Collectif - 1996 ; – Le montreur de Fantasmes (Ed. Paquet) 1999 ; – A Frounz (Ed. Le Studio) 1999 ; – Le Poulpe : Le saint des seins (Scèn. G. Nicloux - Ed. 6 Pieds Sous Terre) 2000 ; – Scott Joplin (Ed. BDMUSIC) 2005. 20 BIOGRAPHIE CHARLIE PARKER 24 BIOGRAPHY CHARLIE PARKER 27 DISCOGRAPHIE CD1 CHARLIE PARKER (1945–1951) 28 DISCOGRAPHIE CD2 CHARLIE PARKER (1947–1952) BDJAZZ EST UNE COLLECTION DES ÉDITIONS BDMUSIC / DIRECTEUR DE LA COLLECTION BRUNO THÉOL / SÉLECTION & TEXTES CHRISTIAN BONNET & CLAUDE CARRIÈRE / TRANSLATION MARTIN DAVIES / TRANSFERTS & MASTERING CHRISTOPHE HÉNAULT & ALEXIS FRENKEL / STUDIO ART & SON PARIS / DESIGN GRAPHIQUE RENAUD BARÈS BDJZ009 (P) & (C) 2011 BDJAZZ PARIS – www.bdmusic.fr ACHEVÉ D’IMPRIMER EN SEPTEMBRE 2011. TOUS DROITS DE TRADUCTION, DE REPRODUCTION ET D’ADAPTATION STRICTEMENT RÉSERVÉS POUR TOUT PAYS. TOUTE REPRODUCTION, MÊME PARTIELLE DE CET OUVRAGE EST INTERDITE. TOUTE COPIE OU REPRODUCTION EST UNE CONTREFAÇON PASSIBLE DES PEINES PRÉVUES PAR LA LOI DU 11 MARS 1957 SUR LA PROTECTION DES DROITS D’AUTEUR. DÉPÔT LÉGAL OCTOBRE 2011 / ISBN 2-84907-009-2. 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 BIOGRAPHIE CHARLIE PARKER saxophoniste, compositeur Charlie Christopher Parker naît le 29 août 1920 à Kansas City, Kansas, États-Unis. -

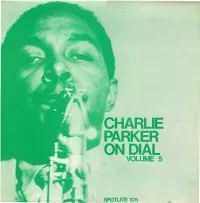

Charlie Parker on Dial Volume 5

ON KLACT-OVEESEDS-TENE VOlis one of Charlie Parker's most Bird turns these famous jazzmen around with his so TheCHARLIE reissue of Charlie Parker's historicalPARKER recording sessions for Dial Records continues on Spotlite Volume 5 with the fascinating and original compositions. The stirring, march-like reconstructionAH. complete chronological sequence of the November 4, 1947 introduction is a Parker creation, although some reviewers date at WOR Studios, Thirty-Ninth Street and Broadway, accused Bird of plagiarism when the record first appeared, The r.construction of the final Parker date for Dial Records New York City. This session took place early Tuesday because the same figure had been used as the theme on THE at WOR, Wednesday, December 17, 1947 will appear on evening and was supervised by Ross Russell, president and CHASE by Dexter Gordon and Wardell Gray, recorded for Spotlite 106. director of artists and repertoire for Dial Records. The Dial in Hollywood, June 12, 1947. Actually the tenor recording engineer, as with all Dial sessions in New York, was saxophonists had picked Bird's brains at a jam session on Doug Hawkins, who combined a license as an acoustical Central Avenue in Los Angeles earlier that year and, engineer with a music degree from Juilliard School of Music. remembering the strange and effective figure, and being stuck PERSONNEL for a theme for their saxophone duel, had fallen back on The personnel of the Charlie Parker Quintet—Parker, Miles Charlie s material. It was Charlie's all along and may have Davis, Duke Jordan, Tommy Potter and Max Roach—was the been first played by him much earlier than 1947. -

Charlie Parker Memorial Mp3, Flac, Wma

Charlie Parker Memorial mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Memorial Country: Japan Released: 2007 Style: Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1929 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1647 mb WMA version RAR size: 1937 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 834 Other Formats: MP1 VQF TTA AC3 WMA MPC MP4 Tracklist A1 Another Hair Do A2 Bluebird A3 Bird Gets The Worm A4 Barbados A5 Constellation A6 Parker's Mood B1 Ah-Leu-Cha B2 Perhaps B3 Perhaps B4 Marmaduke B5 Steeplechase B6 Merry Go Round B7 Buzzy Companies, etc. Record Company – Columbia Music Entertainment Credits Bass – Curley Russell* (tracks: A4 to B6), Tommy Potter (tracks: A1 to A3) Drums – Max Roach Edited By – Ozzie Cadena Piano – Bud Powell (tracks: B7), Duke Jordon* (tracks: A1 to A3), John Lewis (tracks: A4 to B6) Trumpet – Miles Davis Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Savoy MG 12000, Charlie Charlie Parker Records, MG 12000, US 1955 MG-12000 Parker Memorial (LP, Album) Savoy MG-12000 Records Charlie Parker Charlie Memorial Vol. 1 (CD, CY-78982 Savoy Jazz CY-78982 Japan 1995 Parker Album, Mono, RE, RM, Min) Charlie Parker Charlie Savoy COJY-9012 Memorial (LP, Album, COJY-9012 Japan 1992 Parker Records Mono, RE, RM) Charlie Memorial Vol. II (LP, 30 SA 6008 Musidisc 30 SA 6008 France 1966 Parker Comp) Charlie Parker Charlie Memorial Vol. 1 (CD, COCY-78261 Savoy Jazz COCY-78261 Japan 1994 Parker Album, Mono, Ltd, Promo, RE, RM, Pap) Related Music albums to Memorial by Charlie Parker Charlie Parker - Charlie Parker Savoy Days Vol 2. -

Charlie Parker on Dial Volume 4 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Charlie Parker Charlie Parker On Dial Volume 4 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Charlie Parker On Dial Volume 4 Country: Japan Released: 1976 Style: Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1303 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1660 mb WMA version RAR size: 1232 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 441 Other Formats: MP3 DXD MOD WMA XM VOC WAV Tracklist A1 Dexterity 2:56 A2 Dexterity 2:56 A3 Bongo Bop 2:42 A4 Bongo Bop 2:42 A5 Dewey Square 3:25 A6 Dewey Square 3:00 A7 Dewey Square 3:04 B1 The Hymn 2:29 B2 The Hymn 2:26 B3 Bird Of Paradise 3:05 B4 Bird Of Paradise 3:06 B5 Bird Of Paradise 3:09 B6 Embraceable You 3:41 B7 Embraceable You 3:17 Companies, etc. Recorded At – WOR Studios Credits Alto Saxophone – Charlie Parker Bass – Tommy Potter Drums – Max Roach Engineer – Doug Hawkins Piano – Duke Jordan Producer – Ross Russell Trumpet – Miles Davis Notes WOR Studios, Broadway at 38th. Street, New York City - Tuesday, October 28, 1947. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Charlie Charlie Parker On Dial Volume Spotlite 104 104 UK 1970 Parker 4 (LP, Comp, Mono) Records Charlie Charlie Parker On Dial Volume Spotlite 104 104 UK 1972 Parker 4 (LP, Comp, Mono, RP) Records Charlie Charlie Parker On Dial Volume Spotlite 104 104 UK 1972 Parker 4 (LP, Comp, Mono) Records Charlie Charlie Parker On Dial Volume Spotlite 104 104 UK 1972 Parker 4 (LP, Comp, Mono) Records Charlie Charlie Parker On Dial Volume Spotlite 104 104 UK 1975 Parker 4 (LP, Comp, Mono, RP) Records Related Music albums to Charlie Parker On Dial Volume 4 by Charlie Parker Charlie Parker - Charlie Parker On Dial Volume 2 Charlie Parker - Cool Blues Charlie Parker - L' Inoubliable Charlie Parker / Charlie Parker All Star Sextet Charlie Parker - Quartet, Quintet & Sextet Charlie Parker / Miles Davis - Bird & Miles Charlie Parker - The Bird Returns Charlie Parker - Alternate Masters Vol.2 Charlie Parker - Charlie Parker On Dial Volume 5 Charlie Parker - Charlie Parker On Dial Volume 1 Miles Davis - Miles To Go. -

Ladders of Thirds and Tonal Jazz Melody

Ladders of Thirds and Tonal Jazz Melody Example 1 is from Miles Davis's 1956 recording of "Bye Bye Blackbird."1 In both passages, over a II–V–I progression, Davis arpeggiates up from G and then down to F. Many melody notes lie beyond the triad, yet sound relatively stable, rather than ornamental. For instance, the F chord's seventh and ninth are departed by leap. And the cadential C7 chord finds no expression in Davis's melody. In the upper staff, m. 2, the A merely caps the arpeggio arising from G in the previous measure. In the lower staff in the same place, though the high F "resolves" by step to E, as is typical for Gm7–C7, the E's continuation into the next measure defines it as the major seventh of F: Davis presents Gm7–FM7 as two clean tetrachords, up then down—no C7. These two phenomena—stable, unresolved dissonances and apparent conflict between melody and harmony—are altogether typical of tonal jazz melody, and distinguish it from the common practice.2 In this paper, I explain these phenomena using two theoretical tools: "ladders of 1 All transcriptions are by the author and are notated at concert pitch. All of the recordings are fairly easy to locate on YouTube or other online resources. Chord symbols are simplified: "Bb"/"Bbm" indicates a triad plus some combination of major seventh, added sixth, and ninth (often functioning as local tonic); extensions beyond the seventh are not listed. 2 The term "tonal jazz melody" deliberately dodges the question of composition versus improvisation (cf. -

Herbie Hancock

kwiecień 2011 Internetowa gazeta poświęcona muzyce improwizowanej SPIS TREŚCI 2 Wydarzenia 3 Płyty RadioJAZZ.FM poleca Nowości płytowe 7 Koncerty i festiwale RadioJAZZ.FM POLECA 8 Lotos Jazz Festival – 13. Bielska Zadymka Jazzowa 15 Wywiad z Tomaszem Grochotem 18 Oleg Kireyev + Keith Javors Quartet 19 James Carter Organ Trio 21 Kanon Jazzu 29 Wspieram RadioJAZZ.FM 32 Sylwetki Stanley Jordan 35 Nowa audycja „Mój Patefon” Agnieszki Antoniewskiej 35 Kalendarium kwietnia Dołącz do nas na Facebooku http://www.facebook.com/radiojazz.fm Wydawca Fundacja Popularyzacji Muzyki Jazzowej fot. Bogdan Augustyniak fot. Redakcja Internetowa gazeta poświęcona muzyce improwizowanej kwiecień 2011 Wydarzenia Adam Pierończyk Quintet, Komeda – The In- 12 marca nocent Sorcerer, Jazzwerkstatt/ Muzeum PW Zmarł Joe Morello, perkusista m.in. Dave Bru- 4250079758715 beck Quartet, urodził się 17 czerwca 1928r. Warsaw Paris Jazz Quintet oraz orkiestra sym- foniczna Perfect Girls &Friends za płytę Cho- 3 marca pin Symphony Jazz Project, Blue Note Agencja Sonny Rollins i Quincy Jones zostali uhonorowa- Artystyczna 5907505870013 ni przez Prezydenta Baracka Obamę medalami Aga Zaryan, Looking Walking Being, Blue National Medal of Arts. Koncert artysty w na- Note Records 6313902 szym kraju zapowiadany jest na jesień tego roku. Fonograficzny Debiut Roku: 15 lutego Maciej Fortuna Quartet Zmarła Karin Stanek, pierwsza polska rock’n’rollowa wokalistka, urodziła się 18 sierp- Robert Kubiszyn New Trio ( Jan Smoczyński, nia 1946 lub 1943r. (wg różnych źródeł) Mateusz Smoczyński, Alex Zinger) W dniach 16-20 lutego Jazzowy Kompozytor Roku: Odbył się Lotos Jazz Festival 13 – Bielska Maciej Kocin Kociński, Robert Kubiszyn, Zadymka Jazzowa – ubiegłoroczna edycja zo- Adam Pierończyk, Jan Smoczyński, Michał stała uznana przez czytelników „Jazz Forum” za Tokaj najlepszy festiwal jazzowy w Polsce. -

Jazzlondonlive Jan 2018

JAZZLONDONLIVE JAN 2018 02/01/2018 ARCHDUKE, WATERLOO 19:30 FREE 04/01/2018 CLOCKTOWER CAFE, CROYDON 12:00 FREE BARRY GREEN 03/01/2018 PIZZAEXPRESS JAZZ CLUB, SOHO 19:00 DAVE LEWIS TRIO £20 02/01/2018 RONNIE SCOTT'S 19:30 £15 - £35 04/01/2018 LE QUECUMBAR, BATTERSEA 19:00 FREE 01/01/2018 BOATERS INN, KINGSTON 14:00 FREE SCOTT HAMILTON QUARTET BEATS & PIECES BIG BAND RESIDENCY - WITH BEFORE 8PM, £6 THEREAFTER MATT WATES QUARTET XMAS JAZZ SPECIAL Matt Wates - sax, Leon Greening, piano, Julian SPECIAL GUESTS! MAIN SHOW 03/01/2018 ARCHDUKE, WATERLOO 19:30 FREE ORIANA AND THE CHARMERS - FRENCH CHANSON Director: Ben Cottrell, Saxophones: Anthony Bury - double bass, Matt Fishwick - drums MARTIN BLACKWELL AND SWING Brown, Oliver Dover, Tom Ward, Trumpets: Owen Bryce, Aaron Diaz, Nick Walters,Trombones: Ed 01/01/2018 ROYAL FESTIVAL HALL, SOUTHBANK Horsey, Richard Foote, Rich McVeigh, Guitar: 03/01/2018 RONNIE SCOTT'S 19:30 £15 - £35 04/01/2018 PIZZAEXPRESS JAZZ CLUB, SOHO 19:00 CENTRE 15:00 FREE Anton Hunter, Keys: Richard Jones, Bass: Mick BEATS & PIECES BIG BAND RESIDENCY - WITH £20 Bardon, Drums: Finlay Panter, Sound engineer: NEW YEAR'S DAY CEILIDH CLORE BALLROOM Alex Fiennes SPECIAL GUESTS! MAIN SHOW SCOTT HAMILTON QUARTET Get ready to dance as the Ceilidh Liberation Director: Ben Cottrell, Saxophones: Anthony Front combines music, dance and a generous 02/01/2018 BULL'S HEAD, BARNES 20:00 £11 IN Brown, Oliver Dover, Tom Ward, Trumpets: Owen 04/01/2018 ARCHDUKE, WATERLOO 19:30 FREE sprinkling of theatrics to bring you Ceilidh music Bryce,