Transition Reports (1977) - Commerce Department: Consolidated Issues (5)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ohio, Ex-Seatrain Ohio

NATIONAL REGISTER ELIGIBILITY ASSESSMENT VESSEL: SS Ohio, ex-Seatrain Ohio Seatrain Puerto Rico, the first in a line of seven converted T2 tankers and sistership of the Ohio, underway circa late 1960s. Victory Ships and Tankers, L.A. Sawyer and W.H. Mitchell Vessel History The Seatrain Ohio was built in 1967 as a combination railway car/container‐carrying vessel for Seatrain Lines, Inc. of New York. It was constructed by recombining modified sections from three WWII T2 class tankers.1 The ship spent its active career on charter to the U.S. Military Sea Transportation Service (MSTS),2 which later became the Military Sealift Command (MSC). Engineer Graham M. Brush founded Seatrain Lines in 1928 to ferry railway cars loaded with goods between New Orleans, Louisiana and Havana, Cuba. The vessels were fitted with tracks and other special equipment so that railcars could move directly from the docks into the ships’ holds. The first vessel he adapted to carry railcars was a cargo ship. This vessel, the Seatrain New Orleans, carried loaded freight cars from New Orleans to Cuba for the first time in January of 1929. There were many advantages to this new service. It cut down on the amount of time 1 The T2 tanker, or T2, was an oil tanker constructed and produced in large quantities in the U.S. during World War II. The largest "navy oilers" at the time, nearly 500 of them, were built between 1940 and the end of 1945. 2 MSTS was a post-World War II combination of four predecessor government agencies that handled similar sealift functions. -

Study of U.S. Inland Containerized Cargo Moving Through Canadian and Mexican Seaports

Study of U.S. Inland Containerized Cargo Moving Through Canadian and Mexican Seaports July 2012 Committee for the Study of U.S. Inland Containerized Cargo Moving Through Canadian and Mexican Seaports Richard A. Lidinsky, Jr. - Chairman Lowry A. Crook - Former Chief of Staff Ronald Murphy - Managing Director Rebecca Fenneman - General Counsel Olubukola Akande-Elemoso - Office of the Chairman Lauren Engel - Office of the General Counsel Michael Gordon - Office of the Managing Director Jason Guthrie - Office of Consumer Affairs and Dispute Resolution Services Gary Kardian - Bureau of Trade Analysis Dr. Roy Pearson - Bureau of Trade Analysis Paul Schofield - Office of the General Counsel Matthew Drenan - Summer Law Clerk Jewel Jennings-Wright - Summer Law Clerk Foreword Thirty years ago, U.S. East Coast port officials watched in wonder as containerized cargo sitting on their piers was taken away by trucks to the Port of Montreal for export. At that time, I concluded in a law review article that this diversion of container cargo was legal under Federal Maritime Commission law and regulation, but would continue to be unresolved until a solution on this cross-border traffic was reached: “Contiguous nations that are engaged in international trade in the age of containerization can compete for cargo on equal footings and ensure that their national interests, laws, public policy and economic health keep pace with technological innovations.” [Emphasis Added] The mark of a successful port is competition. Sufficient berths, state-of-the-art cranes, efficient handling, adequate acreage, easy rail and road connections, and sophisticated logistical programs facilitating transportation to hinterland destinations are all tools in the daily cargo contest. -

03-March Page 1 to 22.Pdf

PORTOF HOUSTON OPENS 3 DOCKS, BI6 WAREHOUSE Striving always to improve and expedite service, the Harris County Hous- ton Ship Channel Navigation District in December, 1963, completed three new wharves, 23, 24, 25, and a huge warehouse, 25A. In the last seven years, the District, which governs and operates the Port of Houston, has spent around $31 million in capital improvements. we oeeee You: ¯ Always Specify, via ¯ Six Trunk-lineRailroads ¯ "~BC°’m°nC""rier"r°c’~’i"es¯ 120Steamship Services ¯ HeavyLift Equipment ¯" THE" PORT OF HfILISTON ¯ ¯ MarginalTracks at Shipside Executive Offices: 1519 Capitol Ave. ¯ 28Barge Lines; 90 TankerLines ¯ ¯ Promptand Efficient Service ¯ P.O. Box 2562 Houston, Texas 2 PORT OF HOUSTON MAGAZINE Expedite Your Shipments Via Manchester AmpleStorage Space Large concrete warehousesand gentle ~oandlinggonSUre the best of care for AmpleUnloading Space It’s easy for ships, trucks andrail cars to load and unloadcargo with no delay¯ ....... ........ , : Quick Hgndhng ¯ . ~ Experience, modern eqmpment and con- crete wharvesconveniently located to warehousesmean quicker service. Manchesters modern convenient facilities include: ¯ Concrete wharves ¯ Automatic sprinkler system ¯ Two-story transit sheds ¯ Large outdoor storage area ¯ High-density cotton compresses ¯ Rapid truck loading and unloading ¯ Modern handling methods and equipment For completecargo handling service, useManchester Terminal. Manchester Terminal Corporahon P. O. Box52278 GeneralOffice: CA7-3296 Houston,Texas, 77052 Wharf Office: WA6-9631 - ~hlll]l[lll[lll[I]l[IJl[lllllll[r,l[llll[illl[l!l!lll[lllllll[lllllilllI[lllll]lJlIIIIIIrJil[lll[I]rJ -

A Comparative Analysis of Roll-On-Roll-Off, Lift-On-Lift-Off Cargo Handling Operations

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 1965 A comparative analysis of roll-on-roll-off, lift-on-lift-off cargo handling operations. Heeley, Eric W. L. Monterey, California: U.S. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/11791 YKN° V: ffi ".^SCHOOL A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF ROLL-ON-ROLL-OFF LIFT -ON-LIFT -OFF CARGO HANDLING OPERATIONS ***##*# Eric ¥. L. Heeley A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF ROLL-ON -ROLL-OFF LIFT-ON-LIFT-OFF CARGO HANDLING OPERATIONS b7 Eric ¥. L.,|Heeley Lieutenant, UnitedyS^tes Navy Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MANAGEMENT United States Naval Postgraduate School Monterey, California 19 6 5 si A COMPARATIVE ANAUSIS OF ROLL-ON-ROLL-OFF LIFT-ON-LIFT-OFF CARGO HANDLING OPERATIONS by Eric W. L. Heeley This work is accepted as fulfilling the Research Paper requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MANAGEMENT from the United States Naval Postgraduate School ABSTRACT « The roll-on- roll-<fr£f and lift-on-lift-off cargo handling concepts have developed rapidly in the trans- portation field since the early 1950' s. The utilization of these two concepts has revolutionized the transportation industry. Based on the information available and the comparative analysis made it can be seen that the economical advantages of the lift-on-lift-off operation are more applicable to commercial transportation, whereas the fast turn-around features of the roll-on-roll-off operation are of particular importance in the logistics field for successful support of Military operations TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I, Introduction 1 II • Containerization 8 J III, Roll-on-Roll-off Concept 21 IV* Life-on-Lift-off Concept 37 V. -

History and Regulation of Trailer-On-Flatcar Movement

History and Regulation of Trailer-on-Flatcar Movement JOSEPHINE AYRE, Economist, Economics and Requirements Division, Office of Research and Development, U. S. Bureau of Public Roads "Piggyback," the popular name for trailer-on-flatcar (TOFC) movement, has been one of the greatest technological innova tions in land transportation of recent years, although the idea is not of recent origin. Piggyback development represents an attempt on the part of the railroads to bolster their declining revenues and to reclaim traffic lost over the last few years to the trucking industry. It represents an example of coordination of transport facilities, routes and rates. Each unfavorable ICC decisionhas arrested the development of piggyback for a temporary period thereafter. The Container Case in 1931 killed the incentive for use of containers because the Commission set an unprofitable rate for shippers. The rules laid down in Ex Parte 129 (19 39) were favorable to the development of piggyback service, but it was not until the New York, New Haven and Hartford decision in 1954 that certain principles were established which encouraged piggyback develop ment. Piggyback carloading surged forward thereafter in spite of subsequent ICC investigations. •TRAILER-ON-FLATCAR or "piggyback" as it is commonly called refers to the move ment of loaded or empty highway trailers on railroad flatcars. The term also embraces the tr ansportation of §teel container s on flatcars. Steel containers are a lso utilized on ships ("fishyback") and on planes ("birdyback"); however, only trailer -on-flatcar (TOFC) or piggyback will be discussed in this paper, although the general principles of economy and efficiency are the same. -

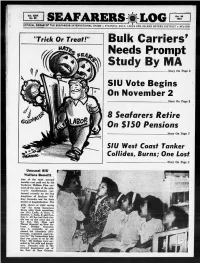

SEAFARERS LOG Oct. 30

t'' Oct. 30 SEAFARERS LOG 1964 OFFICIAL OROAW OF THl SEAFARERS INTERNATIONAL UNION • ATLANTIC, GULF, LAKES AND INLAND WATERS DISTRICT • AFL-CIO Trick Or Treat! Bulk Carriers' Needs Prompt Study By MA -Story On Page 3 SIU Vote Begins On November 2 -Story On Page 3 1; 8 Seafarers Retire ric.-i' r' On $150 Pensions '.:\K' -Story On Page 7 •i-; • •Ji- SIU VIest Coast Tanker Collides^ Burns; One Lost -Story On Page 2 Unusual SIU Welfare Benefit .. One of the most unusual benefits ever paid out by the Seafarers Welfare Plan cov ered all the costs of the quin- tuple tonsilectomies per formed recently on the five daughters of Seafarer Wil liam Gonzalez and for their I»F:li.: . m •' period of hospitalization. The Ir girls, shown at right saying "Ah" for nurse Genevieve Byers after their operations, are (1-r) Lydia, 8; Dora, 7; Darlene, 7; Anna, 6; and Cyn thia, 5. All five had their ton sils out on the same day at the Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat Hospital at^New Or It'1^'" Ir t leans. Brother Gonzalez, who is presently at sea aboard the Afoundria (Wa terman), expressed apprecia tion for "the tremendous help that was given to us by the Plan," His feelings were sec onded by his wife and daugh ters; Gonzalez sails in the steward department out of the Port of New Orleans. mm Pare Tw« SEAFARERS LOG October SO, lOM One SUP Crewmember Perishm§ 51UNA West Coast Tanlcer Burns In Alaska Collision For the past 20 years or so, there has been a gradual change in the ANCHORAGE, Alaska—A few hours after she was involved in a collision with another nature of U.S. -

Intermodal Logisticslogistics Unlockingunlocking Vvaluealue

IntermodalIntermodal LogisticsLogistics UnlockingUnlocking VValuealue Asian Institute of Transport Development E-5, Qutab Hotel, Shaheed Jeet Singh Marg, New Delhi 110 016, India Tel: (91-11) 26856117 Telefax: (91-11) 26856113 Email: [email protected] ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TRANSPORT DEVELOPMENT Intermodal Logistics: Unlocking Value © Asian Institute of Transport Development, New Delhi First published 2007 All rights reserved Published by Asian Institute of Transport Development E-5, Qutab Hotel Shaheed Jeet Singh Marg New Delhi-110 016 INDIA Phones: +91-11-26856117, 26856113 Fax: +91-11-26856113 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Intermodal Logistics Unlocking Value ASIAN INSTITUTE OF TRANSPORT DEVELOPMENT CONTENTS Preface i Abbreviations iii Contextual Information vii Chapter 1: Globalisation and Logistics: The Container Revolution 1 Section I : Maritime Transport Logistics Chapter 2: Maritime Transport Networks and Container Shipping Development 27 Chapter 3: A New Ports Structure: Asia Moves Ahead 45 Section II: Land Transport Logistics Chapter 4: Land Transport Networks: Regional and Subregional 85 Chapter 5: Dry Ports: Sharing Benefits 153 Section III: Facilitation of Multimodal Transport Logistics Chapter 6: Institutional Framework: Cross-border Impediments 167 Section IV: The Way Ahead 193 Annexures 199 References 205 Preface For about 25 years now, national barriers to trade and investment have been dismantled at an unprecedented pace, leading to a degree of integration of product and financial markets that is reminiscent of the pre- twentieth century global economic arrangements. One of the consequences of this has been the spread of production facilities across national borders. Thus, what was started by US multinational firms in the 1960s in Europe has now become a global trend. -

Master Mates and Pilots Febuary 1948

'. In This Issue * Shipping Labor, Management, Work As One * "Cycloid Propulsion": Something New * Planned Sale of Ships Menaees Industry * Days of 'Lakes Carferries Are Reealled Vol. XI FEBRUARY, 1948 No.2 l Partial List of Agreements Held by Masters, Mates and Pilots of America ---- East Coast Stockard Steamship Corporation Hnrt Wood Lumber Co. Agwilines, Inc. Smith & Johnson In~erocean ::)tcamllhip Corporation .<\:Icoll Steamship Co. Sound Transport Corporation Henry J. Kaiser Companies Aml.'l"ican Foreign Steamship Co. Sword Steamship Co. (Permanente :&Ietals Corp.) Americ:m Petroleum Trnnsport (orp. Tankers Oceanic Corporation (Kaiser Company, Inc.) American Republics Lines l'rI. & J. Tracy (Kaiser Cargo, Inc.) American Liberty Lines, Inc. Tugboat Owners & Operators of Port of Key System American~South African Line Philadelphia Kingdom of Thailand (Siam) American SUJ:"ar Co. Union Sulphur Co. Kitsap County Transportation Co, 4· Argonaut Line, Inc. United States Lines Louis Knutson Athmtic Coast Line Railroad Co. U. S. Navigation Co. Libby, McNeill & Libby Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Co. Virginia Ferry Corp. Los Angeles Steamship Co. Chas. T. Banks Towing Line Wellhart Steamship Co. Luckenbach Gulf Steamship Co., Inc Black Diamond Steamship Co. Wessel Duval & Co., Inc. Luckenbach Steamship Co., Inc. • Blidberg Rothchild Co., Inc. West India S.S. Co. Martin Siversten Steamship Co. Boland and Cornelius Wilmore S.S. Co. Martinez-Benicia Ferry & Trans. C Boston Tow BOBt Co. Wilkinson Steamship Co. Matson Navigation Co. o. Brooklyn Eastern District Wood Towing Co. ?tIatson Steamship Co. A. L. llurbank Co. 'Vorth Steamship Company McCormack Steamship Co. Bush Terminal Co. Warner Company lEast Coast-South American SerVice) Buxton Line Great Lakes (Pacific Coast-Puerto Rico-West Indies SI Calmar Steamship Corp. -

14Th Annual Report for Fiscal Year 1975

FOURTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT of the FEDERAL MARITIME COMMISSION Fiscal Year Ended June 30 1975 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE SCOPE OF AUTHORITY AND BASIC FUNCTIONS 1 HIGHLIGHTS OF THE YEAR 3 U S OCEANBORNE COMMERCE IN REVIEW 8 Intermodalism 8 Development of containerization 12 LASH Seabee and Roll On RollOff Services 14 Trends in Trade 15 Freight Rates and Surcharges in Foreign Commerce 24 SURVEILLANCE COMPLIANCE AND ENFORCEMENT 29 Agreements Review 29 Tariff Review 36 Dual Rate Contract Systems 40 Domestic Commerce 41 Terminals 48 Water Pollution Financial Responsibility 53 Ocean Freight Forwarders 58 Passenger Vessel Certification 61 Field Activities 64 Shippers Requests and Complaints 68 Informal Complaints 68 SPECIAL STUDIES AND PROJECTS 69 PROCEEDINGS BEFORE ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGES 77 FINAL DECISIONS OF THE COMMISSION 81 RULEMAKING 87 ACTION IN THE COURTS 89 LEGISLATIVE DEVELOPMENT 94 ADMINISTRATION 101 Statement of Appropriation and Obligation for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30 1974 102 APPENDIX A Statistical Abstract of Filings 103 APPENDIX B Organization Chart 104 FEDERAL MARITIME COMMISSION WASHINGTON DC June 30 1975 1 Helen Delich Bentley Chairman James V Day Vice Chairman Ashton C Barrett Member Clarence Morse Member 1 As of June 30 1975 one vacancy existed on the Commission due to the resignation of Commissioner George H Hearn SCOPE OF AUTHORITY AND BASIC FUNCTIONS The Federal Maritime Commission was established as an independent agency by Reorganization Plan No 7 effective August 12 1961 Its basic regulatory authorities are derived -

SEA TRAIN OHIO HAER TX-111 (Ohio) HAER TX-111 (Mission San Jose) Beaumont Reserve Fleet, Neches River Beaumont Vicinity Jefferson County Texas

SEA TRAIN OHIO HAER TX-111 (Ohio) HAER TX-111 (Mission San Jose) Beaumont Reserve Fleet, Neches River Beaumont vicinity Jefferson County Texas PHOTOGRAPHS PAPER COPIES OF COLOR TRANSPARENCIES WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA REDUCED COPIES OF MEASURED DRAWINGS HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD Seatrain Ohio (Ohio) (Mission San Jose) HAER No. TX-111 Location: Beaumont Reserve Fleet, Neches River, Beaumont vicinity, Jefferson County, Texas Type of Craft: Container, railcar, and vehicle carrier Trade: Military cargo transportation MARAD Design No.: Converted T2-SE-A2 Builder’s Hull No.: various Official Registry No.: 244610 IMO No.: 6621234 Principal Measurements: Length (bp): 539’-6” Length (oa): 559’-11” Beam (molded): 68’ Depth (molded): 39’-3” Draft: 27’ Displacement: 21,240 long tons Deadweight: 12,293 long tons Gross registered tonnage: 8,047 Net registered tonnage: 4,811 Normal continuous shaft horsepower: 10,000 Service speed: 16 knots (The listed dimensions are as-built, but it should be noted that draft, displacement, and tonnages are subject to alteration over time as well as variations in measurement.) Propulsion: Single-screw turbo-electric drive Dates of Construction: 1966–67 (conversion) Designer: Maryland Shipbuilding and Drydock Company, Baltimore, Maryland Builder: Marinship Corporation, Sausalito, California (original components); Maryland Shipbuilding and Drydock Company (conversion) -

Prospects and Problems of the Container Revolution

PROSPECTS AND PROBLEMS OF THE CONTAINER REVOLUTION EDWARD SCHMELTZER· AND ROBERT A. PEAVY·· "Container revolution" is a term which is often and increasingly heard today. Reduced to its simplest denominator, the term connotes no more and no less than a box of freight in motion-a concept as timeless as transportation itself. In the modern context, however, the revolutionized box-now called a containerl-has created a dramatic change in existing systems for the movement of cargo in international commerce by land, ocean, and air carriers.2 The prospects for further change are manifold. At the same time, containerization has raised a myriad of problems, many of which will require solutions before the prospects of change may be implemented an'd fully realized. I. INTRODUCTION The tremendous growth in the use of intermodal containers over the past several years is a matter of common knowledge. For example, in 1965, less than five per cent of the ocean liner cargo transported between Europe and the United States moved in containers; by 1975, it is variously estimated that from 50 per cent to as high as 80-85 per cent of that cargo • Member, Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, Washington, D.C. Mr. Schmeltzer was Managing Director of the Federal Maritime Commission from 1966 to 1969. A.B .• Hunter College, 1950; M.A .• Columbia University, 1951; LL.B .• George Washington University, 1954 . •• Associate, Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, Washington. D.C. B.A .• university of Colorado, 1961; LL.B .• University of Texas. 1966. I. "Container" is referred to in Article 4(5) of the Hague Rules of 1924 as an "article of transport." The United States Coast Guard, which is responsible for approving containers used for international transportation under Customs seal, proposes a definition of "container" as "an article of transport equipment (Iiftvan, portable tank. -

Annual Report for Fiscal Year 1933

Seventeenth Annual Deport OF THE UNITED STATES SHIPPING BOARD Fiscal Year Ended June 30 1933 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON 1933 UNITED STATES SHIPPING BOARD Rear Admiral H I CONE Chairman Capt DAVID W TODD Vice Chairman Capt GATEWOOD S LINCOLN Commissioner SAMUEL GOODACRE Secretary R 2394 TABLE OF CONTENTS I UNITED STATES SHIPPING BOARD Pagr Letter of transmittal Organization 3 General statement 5 Bureau of regulation and traffic 10 Bureau of marine development 20 Bureau of construction and finance 26 Bureau of research 39 Office of the general counsel 40 Secretary 43 II UNITED STATES SHIPPING BOARD MERCHANT FLEET CORPORATION Organization 51 Special features of the years activities Sales of vessels 52 Extent of vessel operations 54 Total results of operations during 1933 55 Cost of cargo services 55 Other operating results 55 Reduction of pay rolls and administrative expenses 56 Reduction of appropriations 56 Supply and operating activities Care of reserve fleet 57 Terminals 57 Fuel purchases and issues 60 Storekeeping activities 61 Traffic General conditions 61 Pooling agreements 61 Special cargo movements 62 Insurance 62 Finance Cash accounts 63 Collection of accounts 64 Securities 64 Collateral securities 64 Cash statement 84 Housing properties 64 Accounting and auditing 65 Special auditing and disbursing activities 65 cu av TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX TABLES Page I Vessels sold and vessels disposed of otherwise than by sale during the fiscal year ended June 30 1933 69 II Vessel property controlled by the United