4 April 1956 INTERNATIONAL TRADE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Release of Ccm Equipments, 25 April 1955; Memorandum To

, ~60906 ; ' 24 USCIB: 29 .11/17 25 April 1955 'l'0F MleimT MEMORANDUM FOR THE MEMBERS OF USCIB: Subject: Release of CCM Equipments to the Turkish Government. References: (a) USCIB 2/21 of 18 July 1952 (Minutes of Item 9 of the 78th Meeting of USCIB). (b) USCIB 2/25 of 21 January 1953. (c) USCIB 2/28 of 14 April 1953. 1. Enclosures 1 and 2 and the information set forth below are circulated for information on action taken and impending in implementation of reference (a). 2. Attention is invited to references (b) and (c). The former includes as enclosure 1 LSIB views on the USCIB decision recorded in ref erence (a). The latter circulated to the members of USCIB a copy of the letter sent from the Chairman, USCIB to the Chainnan, LSIB conveying USCIB 1s comments in response to the above mentioned LSIB views. 3. In consideration of all this the NSA member has suggested, and this office has concurred, that I.BIB should be notified of the current status of the matter. Accordingly, notification, a copy of which is attached hereto as enclosure 2, has been sent on its wa:y by mail to SUSLO, London. 4. In addition to the above the Director, NSA has informed the United States Communications Security Board (on 16 March 1955) and is, as a matter of courtesy, informing the Director, London Communication Security Agency of his action. Enclosures 1. NSA Memo dtd 21 Apr 1955. 2. CIB # 00091 dtd 25 Apr 1955. USCIB: 2!J .11/17 'fOP SECRET Declassified and approved for release by NSA on 04-23-2014 pursuant to E. -

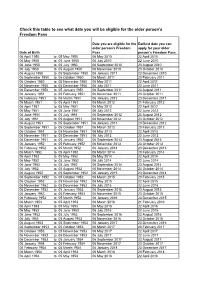

Copy of Age Eligibility from 6 April 10

Check this table to see what date you will be eligible for the older person's Freedom Pass Date you are eligible for the Earliest date you can older person's Freedom apply for your older Date of Birth Pass person's Freedom Pass 06 April 1950 to 05 May 1950 06 May 2010 22 April 2010 06 May 1950 to 05 June 1950 06 July 2010 22 June 2010 06 June 1950 to 05 July 1950 06 September 2010 23 August 2010 06 July 1950 to 05 August 1950 06 November 2010 23 October 2010 06 August 1950 to 05 September 1950 06 January 2011 23 December 2010 06 September 1950 to 05 October 1950 06 March 2011 20 February 2011 06 October 1950 to 05 November 1950 06 May 2011 22 April 2011 06 November 1950 to 05 December 1950 06 July 2011 22 June 2011 06 December 1950 to 05 January 1951 06 September 2011 23 August 2011 06 January 1951 to 05 February 1951 06 November 2011 23 October 2011 06 February 1951 to 05 March 1951 06 January 2012 23 December 2011 06 March 1951 to 05 April 1951 06 March 2012 21 February 2012 06 April 1951 to 05 May 1951 06 May 2012 22 April 2012 06 May 1951 to 05 June 1951 06 July 2012 22 June 2012 06 June 1951 to 05 July 1951 06 September 2012 23 August 2012 06 July 1951 to 05 August 1951 06 November 2012 23 October 2012 06 August 1951 to 05 September 1951 06 January 2013 23 December 2012 06 September 1951 to 05 October 1951 06 March 2013 20 February 2013 06 October 1951 to 05 November 1951 06 May 2013 22 April 2013 06 November 1951 to 05 December 1951 06 July 2013 22 June 2013 06 December 1951 to 05 January 1952 06 September 2013 23 August 2013 06 -

Trusteeship Council

UNITED NATIONS Distr. TRUSTEESHIP LIMITED T/PET.5/L.420 COUNCIL 6 March 1957 ENGLISH ORIGINAL: FRENCH PETITION FROM THE LOCAL COMi,IITTEE .:o:f ±HE 11 tmioN DES POPULATIONS DU CAMIBOUN 11 OF THE NEW,;:BELL DOUALA PRISON y CONCERIIDJG THE CAMEROON$ FRENCH ADMINISTRATION ' • mmER', • < (Circulated in accordance with rule 85, paragraph 2 of the rules . of procedure. of t.he fyusteeship Council) . UNION DES POPUI.ATIONS DU CPJOOOUN .. (UPC) Local Committee, New-Bell Prison, Douala The Douala Local Committee of the UPC, holding its General Assembly in cell No. 18 on 25 Yiay 1956 in commemoration of the historic national week of 22 to 29 Nay 1955, having heard the statements of the following members: NDOOll Ic~sc, Chairman of the Local Committee, Hyacinthe MPAYE, Chairman of the JDC, Th. M. MATIP, an Officer of the Local Connnittee analysing the consequences of the killings and 'barbarous acts perpetrated against the Kamerunia.ns during the month of May 1955 under the orders of the French Government, which is losing its hold on KJIJ,1IBtm, unanimously adopted the following resolution: THE LOCAL COMMITTEE OF THE UPC, DOUAIJ\ PRISON CONSIDERI?-.U that after the Joint Proclamation of 22 April 1955 whereby the sovereign Kamerunian People repudiated the Administering Authorities, they adopted a national flag on 22 May, therc::.fter, Jj Note by the Secretariat: The petition is c·irculated in accordance with the decision taJ;:en by the Standing Committee on Petitions o.t its 403rd meeting held on 4 March 1957. 11his document replaces Section II, paragraph 3, of document T/PET.5/L.99. -

" the Strange Birth Of'cbs Reports'" Revisited

DOCUMENT RESUMEL ED 205 963 CS 206 427 AUTHOR Baughman, James L. TITLE "The Strange Birth of 'CBS Reports'" Revisited. .PUB DATE Aug 81 NOTE 24p.: Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism (64th, East Lansing, M/, August 8-11, 1981). EBBS PRICE MP01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Broadcast industry: *Broadcast TO.evision: Case Studies: *News Reporting: *Programing (Broadcast): Socioeconomic Influences \ IDENTIFIERS *Broadcast History: *CBS !rports ABSTRACT - Aired by the Columbia Broadcasting system (CBS) during the 1960s, "CBS Reports" proved to be one of that network's most honored efferts at television news coverage. CBSchairman, William S. Paley, based his decision to air the show on the presence of a sponsor and in response to the prospect of an open-endedFederal Communications Commission (FCC) Inquiry into network operations and a critics' tempest over the departure of another CBS News Program, ."See It Nov." The path of "CBS Reports" serves to illustrate twopoints: the economics of prograNing in the 1950s did mattergreatly to at least one network deciding for prime time news, andcritics and regulator) probably,did influence such determinations.(HOD) ** 4 *$ * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. a U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION EOVC.ITIONAL RESOURCES AtFORMATION CENTER IERtCt .9 the docutown tve been teprodk.cod es "coned Rom the tenon co oroamabon t*Newry 4 Move changes have been mete to ."Mont teorOducten gyably History Division P0,071.0lva, a opinions maid n the docv meni do not /*cemet', r*Preitat °He. -

Income of Persons in 1954 Equals 1953 Level (Advance Data)

U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE BUREAU OF THE CENSUS W. Bu-, Director aidair we&, isememry Robcrt CURRENT POPULATION REPORTS CONSUMER INCOME \ A~gLlst1955 Washington 25. D. C. Series E!-60, No. 17 - -- - INCCME OF PERSONS IN 1954 EQUALS 1953 LEVEL (Advance data, April 1955 sample survey) The average person's income in 1954 remained appear in more detailed reports to be issued later about the same as during the previous year. For all this year. Other data relating to the income re- persons 14 years old and over receiving any money ceived by the population are avail~blefrom the Per- income, 'the average (median) income was estimated at sonal Income Series of the Department of Conanerce, $2,300 in each year, according to estimates released the Federal Reserve Board Survey of Consumer Fi- today by Robert W. Burgess, Director, Bureau of the nances, Federal income tax data, and Old-Age and Census, Department or Commerce. Survivors Insurance wage record data. These data are collected for different purposes and. therefore, The avemge income of men, which had been ris- .differ in several important respects. A discussion ing steadily between 1945 and 1953, leveled off at or the comparability of these data may be found in $3.200 in 1953 and 1954. Between 1952 and 1953 a Current Population Reports, Series P-60, No. 16, gain or about $100 had been recorded. The propor- "Income of Persons in the United States: 1953." tion of men whose incomes were $5,000 or over rose from 16 percent in 1952 to about 20 percent in 1953 Information on incone was collected in the Bu- and 1954. -

NJDARM: Collection Guide

NJDARM: Collection Guide - NEW JERSEY STATE ARCHIVES COLLECTION GUIDE Record Group: Department of Institutions and Agencies Series: Welfare Reporter [incomplete], 1946-1957 Accession #: 1985.011, 1998.097 and unknown Series #: SIN00002 Guide Date: 4/1996 (JK); rev. 2/1999 (EC) Volume: 1.0 c.f. [2 boxes] Contents Content Note This series consists of an incomplete run of the Department of Institutions and Agencies' monthly publication, the Welfare Reporter. Articles in this publication discuss the various aspects of health, welfare and penology. Included are profiles of administrators and employees, stories on specific institutions, and discussions of trends in the care and treatment of those entrusted to the Department of Institutions and Agencies. NOTE: The New Jersey State Library holds a complete run of the Welfare Reporter from May 1946 to January 1972, when it ceased to be published. It is not clear why "interim" issues were published between 1952 and 1955. Interim Issue 27 (April 1955) includes a subject and name index for all of the interim issues (copy attached). Contents Box 1 Volume I, Number 2, June 1946 [1 copy]. Volume III, Number 2, June 1948 [1 copy]. Volume IV, Number 9, January 1950 [3 copies]. Volume IV, Number 10, February 1950 [3 copies]. Volume IV, Number 11, March 1950 [3 copies]. Volume IV, Number 12, April 1950 [3 copies]. Volume V, Number 1, May 1950 [3 copies]. Volume V, Number 2, June 1950 [3 copies]. Volume V, Number 9, January 1951 [3 copies]. Volume V, Number 10, February 1951 [3 copies]. Volume V, Number 11, March 1951 [3 copies]. -

Inquiries Concerning the California Cooperative

Inquiries concerning the California Cooperative Oce- anic Fisheries Investigations should be addressed to the State Fisheries Laboratory, California Department of Fish and Game, Terminal Island, California, or to University of California, Scripps Institution of Ocean- ography, La Jolla, California CALIFORNIA COOPERATIVE OCEANIC FISHERIES INVESTIGATIONS Progress Report, 1 April 1955 -30 June 1956 ERRATA Page 19, left-hand column, line 24, For "1955-56" read "1956-57tt, Page 25, left-hand column, line 47. For "Onchorhvnchus tshauvtscha" read "Oncorhynchus tshawtschqTt Page 28, left-hand column, line 38, Deletssentence beginning "All are small and substitute "These are small crustaoeans and pelagic mollusks found in the upper layers of the ocean". Page 29, table 11. Phrases "more thant1 and "less than" should appear in column headed 'lNumber of fish". Phmse"more than" should be deleted from entries from 1938 through 1950, Page 4.4, right-hand column, line 26, For "guttaral' read Itguttatall. PPtvm - 1/7/57 - 6000 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL 1 July 1956 HONORABLE GOODWIN J. KXIGHT Governor of the State of California Sacramento, California DEARSIR: We respectfully submit a report on the progress of the California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations for the period 1 April 1955 to 30 June 1956. For several years the agencies cooperating in this program have conducted research on other fishes than the sardine. This work has been only briefly reported on in the past. In this report, we have asked the research agencies, after quickly reviewing their activities during the reporting period, to present individual articles summarizing the status of their knowledge of three impor- tant marine fisheries : the anchovy, the jack mackerel, the Pacific mackerel. -

Gatt Bibliography: First Supplement 1954

GATT BIBLIOGRAPHY: FIRST SUPPLEMENT 1954 - June 1955 • GATT Secretariat Villa le Bocage Palais des Nations Geneva Switzerland August 1955 Spec(62)7 INTRODUCTION The GATT Bibliography which was published in March 195^ covered the period from 19^7 to the end of 1955. This First Supplement lists the books, pamphlets, articles and periodicals, newspaper reports and editorials and miscellaneous material including texts of lectures, which have been noted during the period from January 195^ to June 1955. A small number of items falling within the earlier period, but not recorded in the original Bibliography, has been added. It should be noted that the section of the Bibliography dealing with the Text of the General Agreement has not been brought up to date because this material, together with other GATT publications, is fully dealt with in the List of Material relating to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, obtainable free of charge from the secretariat. The seventh edition of this list was issued in August 1955. Spec(62)7 Page 2 1948 El Acuerdo general de Aranceles y Comercio. Comercio exterior (Lima) Noviembre 1948 122Q Bruno, C. La nuova tariffa doganale itallana e le trattative multilateral! del GATT. Tndustria italiana elettrotecnica (Milano) novembre-dicembre 1950. Eichhorn, Fritz. The international customs tariff discussion in Torquay and Germany. Uebersee-Post (Nurenberg) No. 4l, 1950. Die Liêberalisierung des Welthàndels. Eih Bericht iiber die Durchfubxûng des Allgemeinen Abkommens iiber Zolltariffe und Handel auf Grund der4. ; interna- tionalen Handelskonferenz in Genf vom 23. Pebruar bis 3« April 1950. Europa- Archiv (wien) No. 5, 20. Juli 1950. -

EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS, OFFICE OF: Printed Material, 1953-61

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS, OFFICE OF: Printed Material, 1953-61 Accession A75-26 Processed by: TB Date Completed: December 1991 This collection was received from the Office of Emergency Preparedness, via the National Archives, in March 1975. No restrictions were placed on the material. Linear feet of shelf space occupied: 5.2 Approximate number of pages: 10,400 Approximate number of items: 6,000 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE This collection consists of printed material that was collected for reference purposes by the staff of the Office of Defense Mobilization (ODM) and the Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization (OCDM). The material was inherited by the Office of Emergency Preparedness (OEP), a successor agency to ODM and OCDM. After the OEP was abolished in 1973 the material was turned over to the National Archives and was then sent to the Eisenhower Library. The printed material consists mostly of press releases and public reports that were issued by the White House during the Eisenhower administration. These items are arranged in chronological order by date of release. Additional sets of the press releases are in the Kevin McCann records and in the records of the White House Office, Office of the Press Secretary. Copies of the reports are also in the White House Central Files. The collection also contained several books, periodicals and Congressional committee prints. These items have been transferred to the Eisenhower Library book collection. CONTAINER LIST Box No. Contents 1 Items Transferred -

(Y:F~~{UA___-/Iff~F§1UA

187·187' RESOLUTION NO. NO. 43• 43 • A RESOLUTION RESOLUTION AUTHORIZING AUTHORIZING THE PUBLICNrIONTHE PUBLICA'rION OF AS ESTIMATE OF AS ESTIMATE OF EXOENSESEXOENSES FOR FOR ALL PURPOSESALL PURPOSES FOR THE VILLAGEFOR THE OF VILLAGE KUNA FOR THEOF KUNA FOR THE FISCAL YEAR YEAR BEGnmING BEGIN1HNG THE 1ST THE DAY OF1ST MAY DAY 1954, OF AND MAY ENDING 1954, THE AND ENDING THE • 30TH DAY DAY OF APRILOF APRIL 1954. 195 4 •. BE IT IT RESOLVED RESOLVED BY THE BY CHAIRMAN THE CHAIRMAN AND BOARD AMD OF TRUSTEES BOARD OF TRUSTEE:> OF THE VILLAGE VILLAGE OF KUNA:OF KUNA: Section 1. 1. The The fOllowing following classified classified estimate estimate of the probable of the probable amount of of money money necessary necessary to be raised to be for raised all purposes for all in thepurposes in the Village of of Kuna, Kuna, for thefor fiscal the yearfiscal beginning year beginning the 1st day of the 1st day of May 1954, 1954, and and ending ending the 30th the day 30th of April day 1955, of April be pUblished 1955, be published for two two sucoessive successive weeks weeks in the Kunain the Herald, Kuna a weeklyHerald, newspaper a weekly newspaper published in in the the Village Village of Kuna. of Kuna. Section 2. 2, That That a statement a statement of the entire of the revenue entire of therevenue Village of the Village \ for thethe previous previous fiscal fi~cal year isyear as follOWS: is as fo11ows: General receipts TaxGeneral receipts receipts---------------------------7~69~977269.97 TaxBalance receipts-------------------------------6183.19 on hand 6183.19 Balance on hand----------------------------4789.084~89.08 Section 3. -

SURVEY of CURRENT BUSINESS July 1955

JULY 1955 U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE OFFICE OF BUSINESS ECONOMICS NATIONAL INCOME N SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE FIELD SERVICE Albuquerque, N. Mex. Los Angeles 15, Calif. No. 7 321 Post Office BIdg. 1031 S. Broadway JULY 1955 Atlanta 5, Ga. Memphis 3, Tenn. 50 Seventh St. NE. 229 Federal BIdg, Miami 32 FIa Boston 9t Mass. > - U. S. Post Office and 300 NE- Fir8t Ave. Courthouse BIdg. Minneapolis 2, Minn. Buffalo 3, N. Y. 2d Ave. South and r lational Jsncome I lumber 117 Ellicott St. 3d St. New Orleans 12, La. Charleston 4, S. C. Area 2, 333 St. Charles Ave. PAGE Sergeant Jasper BIdg. THE BUSINESS SITUATION. 1 New York 17, N. Y. Cheyenne, Wyo, 110 E. 45th St. 307 Federal Office BIdg. Philadelphia 7, Pa. 1015 Chestnut St. Chicago 6, 111. 226 W. Jackson Blvd. Phoenix, Ariz. 137 N. Second Ave. Cincinnati 2, Ohio NATIONAL INCOME AND PRODUCT 442 U. S. Post Office Pittsburgh 22, Pa. OF THE UNITED STATES, 1954 4 and Courthouse 107 Sixth St. Cleveland 14, Ohio Portland 4, Oreg. List of Statistical Tables 5 1100 Chester Ave. 520 SW. Morrison St. National Income and Product Accounts 6 Dallas 2, Tex. Reno, Nev. 1114 Commerce St. 1479 Wells Ave. Denver 2, Colo. Richmond 20, Va. 142 New Customhouse 900 N. Lombardy St. Detroit 26, Mich. St. Louis 1, Mo. 230 W. Fort St. MONTHLY BUSINESS STATISTICS....S-1 to S-40 1114 Market St, El Paso, Tex. New or Revised Statistics • •. 28 Chamber of Commerce Salt Lake City 1, Utah BIdg. -

Women's Pension Pack, Part of the Pensions Education Campaign

Women’s Pension Pack, part of the pensions education campaign Front Back Reckoner (front) Reckoner (rear) Reckoner (transcription of copy, front) If you were born between 6 April 1950 and 5 November 1952, use this side. If not, please look on the other side. [Slide covers birthdays from 6.4.1950 to 5.11.1952] [Date of birth] [Pension age date] [Pension age (in years and months)] [coloured box] Pull the card up to find out your state pension date [coloured box ends] Change to the state pension age for women From 6 April 2020, state pension age for both men and women will be 65. The Government will introduce the change gradually from age 60 to 65 for women over a 10-year period from 2010 to 2020. When will you get your state pension? If you are a woman born before 6 April 1950, you can claim your state pension at 60. If you are a woman born on or after 6 April 1955, you can claim your state pension at 65. If you are a woman born between 6 April 1950 and 5 April 1955, your state pension age will be between 60 and 65, depending on your date of birth. This table shows your state pension age and the date you will reach state pension age. [Social Security logo] This leaflet is for guidance only. It is not a complete statement of the law. © Crown Copyright. Produced by the Department for Social Security. Produced in the UK. Printed December 2000. PM6i. www.pensionguide.gov.uk Reckoner (transcription of copy, back) If you were born between 6 November 1952 and 6 April 1955 use this side.