" the Strange Birth Of'cbs Reports'" Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHCA): Videotapes of Public Affairs, News, and Other Television Broadcasts, 1973-77

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library White House Communications Agency (WHCA): Videotapes of Public Affairs, News, and Other Television Broadcasts, 1973-77 WHCA selectively created, or acquired, videorecordings of news and public affairs broadcasts from the national networks CBS, NBC, and ABC; the public broadcast station WETA in Washington, DC; and various local station affiliates. Program examples include: news special reports, national presidential addresses and press conferences, local presidential events, guest interviews of administration officials, appearances of Ford family members, and the 1976 Republican Convention and Ford-Carter debates. In addition, WHCA created weekly compilation tapes of selected stories from network evening news programs. Click here for more details about the contents of the "Weekly News Summary" tapes All WHCA videorecordings are listed in the table below according to approximate original broadcast date. The last entries, however, are for compilation tapes of selected television appearances by Mrs. Ford, 1974-76. The tables are based on WHCA’s daily logs. “Tape Length” refers to the total recording time available, not actual broadcast duration. Copyright Notice: Although presidential addresses and very comparable public events are in the public domain, the broadcaster holds the rights to all of its own original content. This would include, for example, reporter commentaries and any supplemental information or images. Researchers may acquire copies of the videorecordings, but use of the copyrighted portions is restricted to private study and “fair use” in scholarship and research under copyright law (Title 17 U.S. Code). Use the search capabilities of your PDF reader to locate specific names or keywords in the table below. -

Downs, Maria” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 128, folder “Downs, Maria” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 128 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford- Presidential Library THE WHITE: HOUSE WASHINGTON December 22, 1975 MEMORANDUM FOR :MARIA DOWNS FROM: Connie Gerrard ( ~- '-./I..-" These are 'the press people Ron Nessen would like to have invited to the din...'ler in honor of Prime Minister Rabin in late January: Mr. and Mrs. Loyd Shearer Parade Magazine 140 North Hamilton Street Beverly Hills, California 90211 Phone: 213-472-1011 Mr. and Mrs. Herb Kaplow ABC Office: 1124 Connecticut Avenue, NW Washington, D. C. Phone: 393-7700 Home: 211 Van Buren Street Falls Church, Virginia 22046 Phone: 532-2690 Mr. and Mr,~. Saul Kohler Newhouse Newspapers Office: 1750 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20006 Phone: 298-7080 Hoxne: 714 Kerwin Road Silver Spring, Maryland 20901 Phone: 593-7464 -2- - Mr. -

CBS NEWS 2020 M Street N.W

CBS NEWS 2020 M Street N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 FACE THE NATION as broadcast over the CBS Television ~et*k and the -.. CBS Radio Network Sunday, August 6, 1967 -- 12:30-1:00 PM EDT NEWS CORREIS PONDENTS : Martin Agronsky CBS News Peter Lisagor Chicago Daily News John Bart CBS News DIRECTOR: Robert Vitarelli PRODUCEBS : Prentiss Childs and Sylvia Westerman CBS NEWS 2020 M Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEFSE HIGHLIGHTS FROM REMARKS OF HONORABLE EVERETT DIREEN, ,- U.S. SENATOR, REPUBLICAN OF ILLINOIS, ON "FACE THE NATI(3N" ON THE CBS TELEVISION AND THE CBS RADIO NETWORKS, SUNDAY, AUGUST 6, 1967 - 12:30-1:00 PM EST: -PAGE Riots and Urban problems Presented Republican Party statement blaming Pres. Johnson for riots, but would personally be cautious about allegations 1 and 13 In a good many communities there is evidence of outside in£luences triggering riots If conditions not ameliorated--will be "one of the monumental in '68" 3 issues -- - . -- - Congress has -not been "niggardly"--will kead figures to _Mayor Jerome Cavanagh before the Committee 8 Cincinnati police chief told Committee city was in good shape 9 Stokley Carmichael--treason is a sinister charge--must be proven 17 Vietnam Supports President ' s policy--he has most expert advice 4 and 5 7 Gun control bill Can better be handled at state level Would go along with moderate bill 4R. AGRONSKX: Senator Dirksen, a recent Republican Party ;tatement read by you blamed President Johnson for the racial riots. Your Republican colleague, Senator Thrus ton rIorton, denounced this as irresponsible. -

The History Department Newsletter

The HISTORY DEPARTMENT NEWSLETTER Fall 2016 Table of Contents Notes from the Department Chair …………………..... 2-3 Faculty News ……………………………………………… 4-15 Prizes and Awards …………………………………………. 15-17 2015 Fall Honors Day Recipients 2016 Spring Honors Day Recipients Phi Beta Kappa Cork Hardinge Award Justin DeWitt Research Fellowship 2016 The Lincoln Prize Events and Organizations …………………........................ 18-20 Alumni Lecture Fortenbaugh Lecture Phi Alpha Theta Internships ……………………………………………… 20-21 Pohanka Internships Study Abroad Students ……………………........................ 21-24 Department News …………………………………………. 25-30 Book Notes Department Journals ……………………………………… 31 Historical Journal Journal of Civil War Era Studies In Memoriam: George Fick ………………........................ 32-33 Alumni News ……………………………………………… 34-64 Alumni News Send us your news 2 From the History Department Chair by Timothy Shannon Another year has passed in Weidensall Hall, and change is evident in the History Department. This year we welcomed Clare Crone as our new office administrator, and she has done splendid work with our faculty and students. Those of you who might be missing Becca Barth, have no fear: you can visit her when you are on campus at her new position in Career Services. Weidensall lobby also got an upgrade this year with the arrival of new furniture (purple is out; autumnal oranges and brown are in). Highlights from the History Department’s calendar this year included our annual Alumni Lecture, which featured attorney Rachel Burg, ’08, who talked with our students about her experiences as a public defender in Miami, Florida. At Career Night in the spring semester, three History Department alumni returned to campus to share their post-graduate career paths with our students: Brent LaRosa, ’00, who works as a foreign service officer for the U.S. -

Edward R. Murrow

ABOUT AMERICA EDWARD R. MURROW JOURNALISM AT ITS BEST TABLE OF CONTENTS Edward R. Murrow: A Life.............................................................1 Freedom’s Watchdog: The Press in the U.S.....................................4 Murrow: Founder of American Broadcast Journalism....................7 Harnessing “New” Media for Quality Reporting .........................10 “See It Now”: Murrow vs. McCarthy ...........................................13 Murrow’s Legacy ..........................................................................16 Bibliography..................................................................................17 Photo Credits: University of Maryland; right, Digital Front cover: © CBS News Archive Collections and Archives, Tufts University. Page 1: CBS, Inc., AP/WWP. 12: Joe Barrentine, AP/WWP. 2: top left & right, Digital Collections and Archives, 13: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University; bottom, AP/WWP. Tufts University. 4: Louis Lanzano, AP/WWP. 14: top, Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; 5 : left, North Wind Picture Archives; bottom, AP/WWP. right, Tim Roske, AP/WWP. 7: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University. Executive Editor: George Clack 8: top left, U.S. Information Agency, AP/WWP; Managing Editor: Mildred Solá Neely right, AP/WWP; bottom left, Digital Collections Art Director/Design: Min-Chih Yao and Archives, Tufts University. Contributing editors: Chris Larson, 10: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts Chandley McDonald University. Photo Research: Ann Monroe Jacobs 11: left, Library of American Broadcasting, Reference Specialist: Anita N. Green 1 EDWARD R. MURROW: A LIFE By MARK BETKA n a cool September evening somewhere Oin America in 1940, a family gathers around a vacuum- tube radio. As someone adjusts the tuning knob, a distinct and serious voice cuts through the airwaves: “This … is London.” And so begins a riveting first- hand account of the infamous “London Blitz,” the wholesale bombing of that city by the German air force in World War II. -

The Edward R. Murrow of Docudramas and Documentary

Media History Monographs 12:1 (2010) ISSN 1940-8862 The Edward R. Murrow of Docudramas and Documentary By Lawrence N. Strout Mississippi State University Three major TV and film productions about Edward R. Murrow‟s life are the subject of this research: Murrow, HBO, 1986; Edward R. Murrow: This Reporter, PBS, 1990; and Good Night, and Good Luck, Warner Brothers, 2005. Murrow has frequently been referred to as the “father” of broadcast journalism. So, studying the “documentation” of his life in an attempt to ascertain its historical role in supporting, challenging, and/or adding to the collective memory and mythology surrounding him is important. Research on the docudramas and documentary suggests the depiction that provided the least amount of context regarding Murrow‟s life (Good Night) may be the most available for viewing (DVD). Therefore, Good Night might ultimately contribute to this generation (and the next) having a more narrow and skewed memory of Murrow. And, Good Night even seems to add (if that is possible) to Murrow‟s already “larger than life” mythological image. ©2010 Lawrence N. Strout Media History Monographs 12:1 Strout: Edward R. Murrow The Edward R. Murrow of Docudramas and Documentary Edward R. Murrow officially resigned from Life and Legacy of Edward R. Murrow” at CBS in January of 1961 and he died of cancer AEJMC‟s annual convention in August 2008, April 27, 1965.1 Unquestionably, Murrow journalists and academicians devoted a great contributed greatly to broadcast journalism‟s deal of time revisiting Edward R. Murrow‟s development; achieved unprecedented fame in contributions to broadcast journalism‟s the United States during his career at CBS;2 history. -

Release of Ccm Equipments, 25 April 1955; Memorandum To

, ~60906 ; ' 24 USCIB: 29 .11/17 25 April 1955 'l'0F MleimT MEMORANDUM FOR THE MEMBERS OF USCIB: Subject: Release of CCM Equipments to the Turkish Government. References: (a) USCIB 2/21 of 18 July 1952 (Minutes of Item 9 of the 78th Meeting of USCIB). (b) USCIB 2/25 of 21 January 1953. (c) USCIB 2/28 of 14 April 1953. 1. Enclosures 1 and 2 and the information set forth below are circulated for information on action taken and impending in implementation of reference (a). 2. Attention is invited to references (b) and (c). The former includes as enclosure 1 LSIB views on the USCIB decision recorded in ref erence (a). The latter circulated to the members of USCIB a copy of the letter sent from the Chairman, USCIB to the Chainnan, LSIB conveying USCIB 1s comments in response to the above mentioned LSIB views. 3. In consideration of all this the NSA member has suggested, and this office has concurred, that I.BIB should be notified of the current status of the matter. Accordingly, notification, a copy of which is attached hereto as enclosure 2, has been sent on its wa:y by mail to SUSLO, London. 4. In addition to the above the Director, NSA has informed the United States Communications Security Board (on 16 March 1955) and is, as a matter of courtesy, informing the Director, London Communication Security Agency of his action. Enclosures 1. NSA Memo dtd 21 Apr 1955. 2. CIB # 00091 dtd 25 Apr 1955. USCIB: 2!J .11/17 'fOP SECRET Declassified and approved for release by NSA on 04-23-2014 pursuant to E. -

Face the Nation: CBS (Nixon), October 27, 1968

I CBS NBPS 2020 M Stree t, N. W. Hasbinglo·: , D. C. 2003G as broadcast over the CBS Tc levis i. on Network and tlle CBS Radio Ne b·i'Or k Sunday, October 27 , 1968·- 6:30-7:00 P!'·J. EST GUES T:. RIGIARD M. NIXON Republican Candidate fo.1~ President NE\•;6 CORR"ES PONDENTS: Martin Agronsky CBS Ne'i·iS David Broder 'l'he v7ashington Post ,John Hart CBS News DIREC'J.'OTI: Robert Vi ta:re lli PRODUCE RS: Sylvia v7esterman an::'l Prentiss Childs ·.: NOTF: TO EDri'ORS: PJ_ease c recl:it any rruote s or excerpts from this CBS R::Jd:io and T~·d evis ion pro9ram to "Face t he Nation." P RESS CONTACT: Ethel Aaronson - ( 202) 29G-1234 , 1 .0 you .0 1 HR. AGROF:SKY: l"i:C. Nixon, President Johnson today accused ( '1 co N ,......0 2 of making ugly and unfair distortions of An:3r i can defense po.,. N 0 N 0 0 own pcace-rnak.ing efforts. Do you feel that, 3. 3 sitions and of his 0 c 0 .S!a. 4 despite your own moratorium against i t , tl1e peace negoti ations 5 };ave now been brought i nto the polj tical c ampaign? 6 MR. KIXON: I c ertainly do not , b ecause I made it very cle2r 7 that anything I said about the VLetnam negotiations , t hat I 8 would not discuss wh at the negotiators should agree to. I 9 believe that President Johnson should have absolute freedo:11 o f 10 action to negotiate what he finds i s t l!e proper ~~ ind o f settle- 11 ment. -

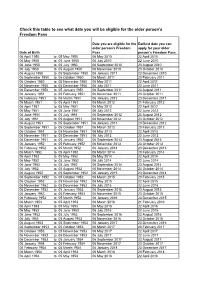

Copy of Age Eligibility from 6 April 10

Check this table to see what date you will be eligible for the older person's Freedom Pass Date you are eligible for the Earliest date you can older person's Freedom apply for your older Date of Birth Pass person's Freedom Pass 06 April 1950 to 05 May 1950 06 May 2010 22 April 2010 06 May 1950 to 05 June 1950 06 July 2010 22 June 2010 06 June 1950 to 05 July 1950 06 September 2010 23 August 2010 06 July 1950 to 05 August 1950 06 November 2010 23 October 2010 06 August 1950 to 05 September 1950 06 January 2011 23 December 2010 06 September 1950 to 05 October 1950 06 March 2011 20 February 2011 06 October 1950 to 05 November 1950 06 May 2011 22 April 2011 06 November 1950 to 05 December 1950 06 July 2011 22 June 2011 06 December 1950 to 05 January 1951 06 September 2011 23 August 2011 06 January 1951 to 05 February 1951 06 November 2011 23 October 2011 06 February 1951 to 05 March 1951 06 January 2012 23 December 2011 06 March 1951 to 05 April 1951 06 March 2012 21 February 2012 06 April 1951 to 05 May 1951 06 May 2012 22 April 2012 06 May 1951 to 05 June 1951 06 July 2012 22 June 2012 06 June 1951 to 05 July 1951 06 September 2012 23 August 2012 06 July 1951 to 05 August 1951 06 November 2012 23 October 2012 06 August 1951 to 05 September 1951 06 January 2013 23 December 2012 06 September 1951 to 05 October 1951 06 March 2013 20 February 2013 06 October 1951 to 05 November 1951 06 May 2013 22 April 2013 06 November 1951 to 05 December 1951 06 July 2013 22 June 2013 06 December 1951 to 05 January 1952 06 September 2013 23 August 2013 06 -

Introduction to the Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows

Broo_9780345497734_2p_fm_r1.qxp 7/31/07 10:32 AM Page ix INTRODUCTION In the following pages we present, in a sin- eral headings. For example, newscasts are gle volume, a lifetime (or several lifetimes) of summarized under News, movie series under television series, from the brash new medium Movies and sports coverage under Football, of the 1940s to the explosion of choice in the Boxing, Wrestling, etc. All other series are 2000s. More than 6,500 series can be found arranged by title in alphabetical order. There here, from I Love Lucy to Everybody Loves is a comprehensive index at the back to every Raymond, The Arthur Murray [Dance] Party cast member, plus appendixes showing an- to Dancing with the Stars, E/R to ER (both nual network schedules at a glance, the top with George Clooney!), Lost in Space to Lost 30 rated series each season, Emmy Awards on Earth to Lost Civilizations to simply Lost. and other information. Since the listings are alphabetical, Milton Network series are defined as those fed out Berle and The Mind of Mencia are next-door by broadcast or cable networks and seen si- neighbors, as are Gilligan’s Island and The multaneously across most of the country. Gilmore Girls. There’s also proof that good Broadcast networks covered are ABC, CBS, ideas don’t fade away, they just keep coming NBC, Fox, CW, MyNetworkTV, ION (for- back in new duds. American Idol, meet merly PAX) and the dear, departed DuMont, Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts. UPN and WB. We both work, or have worked, in the TV Original cable series are listed in two dif- industry, care about its history, and have ferent ways. -

Edward R. Murrow: Journalism at Its Best

ABOUT AMERICA EDWARD R. MURROW JOURNALISM AT ITS BEST TABLE OF CONTENTS Edward R. Murrow: A Life .............................................................1 Freedom’s Watchdog: The Press in the U.S. ....................................4 Murrow: Founder of American Broadcast Journalism ....................7 Harnessing “New” Media for Quality Reporting .........................10 “See It Now”: Murrow vs. McCarthy ...........................................13 Murrow’s Legacy...........................................................................16 Bibliography ..................................................................................17 Photo Credits: 12: Joe Barrentine, AP/WWP. Front cover: © CBS News Archive 13: Digital Collections and Archives, Page 1: CBS, Inc., AP/WWP. Tufts University. 2: top left & right, Digital Collections and Archives, 14: top, Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; Tufts University; bottom, AP/WWP. bot tom, AP/ W WP. 4: Louis Lanzano, AP/WWP. Back cover: Edward Murrow © 1994 United States 5: left, North Wind Picture Archives; Postal Service. All Rights Reserved. right, Tim Roske, AP/WWP. Used with Permission. 7: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University. 8: top left, U.S. Information Agency, AP/WWP; right, AP/WWP; bottom left, Digital Collections Executive Editor: George Clack and Archives, Tufts University. Managing Editor: Mildred Solá Neely 10: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts Art Director/Design: Min-Chih Yao University. Contributing editors: Chris Larson, 11: left, Library of American -

Trusteeship Council

UNITED NATIONS Distr. TRUSTEESHIP LIMITED T/PET.5/L.420 COUNCIL 6 March 1957 ENGLISH ORIGINAL: FRENCH PETITION FROM THE LOCAL COMi,IITTEE .:o:f ±HE 11 tmioN DES POPULATIONS DU CAMIBOUN 11 OF THE NEW,;:BELL DOUALA PRISON y CONCERIIDJG THE CAMEROON$ FRENCH ADMINISTRATION ' • mmER', • < (Circulated in accordance with rule 85, paragraph 2 of the rules . of procedure. of t.he fyusteeship Council) . UNION DES POPUI.ATIONS DU CPJOOOUN .. (UPC) Local Committee, New-Bell Prison, Douala The Douala Local Committee of the UPC, holding its General Assembly in cell No. 18 on 25 Yiay 1956 in commemoration of the historic national week of 22 to 29 Nay 1955, having heard the statements of the following members: NDOOll Ic~sc, Chairman of the Local Committee, Hyacinthe MPAYE, Chairman of the JDC, Th. M. MATIP, an Officer of the Local Connnittee analysing the consequences of the killings and 'barbarous acts perpetrated against the Kamerunia.ns during the month of May 1955 under the orders of the French Government, which is losing its hold on KJIJ,1IBtm, unanimously adopted the following resolution: THE LOCAL COMMITTEE OF THE UPC, DOUAIJ\ PRISON CONSIDERI?-.U that after the Joint Proclamation of 22 April 1955 whereby the sovereign Kamerunian People repudiated the Administering Authorities, they adopted a national flag on 22 May, therc::.fter, Jj Note by the Secretariat: The petition is c·irculated in accordance with the decision taJ;:en by the Standing Committee on Petitions o.t its 403rd meeting held on 4 March 1957. 11his document replaces Section II, paragraph 3, of document T/PET.5/L.99.