The Digest of Justinian, Volume 1 Alan Watson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book I. Title XXVII. Concerning the Office of the Praetor Prefect Of

Book I. Title XXVII. Concerning the office of the Praetor Prefect of Africa and concerning the whole organization of that diocese. (De officio praefecti praetorio Africae et de omni eiusdem dioeceseos statu.) Headnote. Preliminary. For a better understanding of the following chapters in the Code, a brief outline of the organization of the Roman Empire may be given, but historical works will have to be consulted for greater details. The organization as contemplated in the Code was the one initiated by Diocletian and Constantine the Great in the latter part of the third and the beginning of the fourth century of the Christian era, and little need be said about the time previous to that. During the Republican period, Rome was governed mainly by two consuls, tow or more praetors (C. 1.39 and note), quaestors (financial officers and not to be confused with the imperial quaestor of the later period, mentioned at C. 1.30), aediles and a prefect of food supply. The provinces were governed by ex-consuls and ex- praetors sent to them by the Senate, and these governors, so sent, had their retinue of course. After the empire was established, the provinces were, for a time, divided into senatorial and imperial, the later consisting mainly of those in which an army was required. The senate continued to send out ex-consuls and ex-praetors, all called proconsuls, into the senatorial provinces. The proconsul was accompanied by a quaestor, who was a financial officer, and looked after the collection of the revenue, but who seems to have been largely subservient to the proconsul. -

RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian's “Great

ABSTRACT RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy. (Under the direction of Prof. S. Thomas Parker) In the year 303, the Roman Emperor Diocletian and the other members of the Tetrarchy launched a series of persecutions against Christians that is remembered as the most severe, widespread, and systematic persecution in the Church’s history. Around that time, the Tetrarchy also issued a rescript to the Pronconsul of Africa ordering similar persecutory actions against a religious group known as the Manichaeans. At first glance, the Tetrarchy’s actions appear to be the result of tensions between traditional classical paganism and religious groups that were not part of that system. However, when the status of Jewish populations in the Empire is examined, it becomes apparent that the Tetrarchy only persecuted Christians and Manichaeans. This thesis explores the relationship between the Tetrarchy and each of these three minority groups as it attempts to understand the Tetrarchy’s policies towards minority religions. In doing so, this thesis will discuss the relationship between the Roman state and minority religious groups in the era just before the Empire’s formal conversion to Christianity. It is only around certain moments in the various religions’ relationships with the state that the Tetrarchs order violence. Consequently, I argue that violence towards minority religions was a means by which the Roman state policed boundaries around its conceptions of Roman identity. © Copyright 2016 Carl Ross Rice All Rights Reserved Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy by Carl Ross Rice A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2016 APPROVED BY: ______________________________ _______________________________ S. -

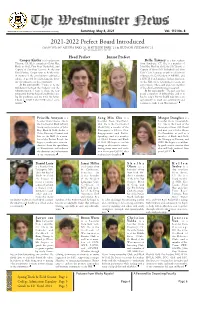

2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced - - - Times

Westminster School Simsbury, CT 06070 www.westminster-school.org Saturday, May 8, 2021 Vol. 110 No. 8 2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced COMPILED BY ALEYNA BAKI ‘21, MATTHEW PARK ‘21 & HUDSON STEDMAN ‘21 CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF, 2020-2021 Head Prefect Junior Prefect Cooper Kistler is a boarder from Bella Tawney is a day student Tiburon, CA. He is a member of John Hay, from Simsbury, CT. She is a member of Black & Gold, First Boys’ Basketball, and John Hay, Black & Gold, the SAC Board, a Captain of First Boys’ lacrosse. As the new Captain of First Girls’ Basketball and First Head Prefect, Cooper aims to be the voice Girls’ Cross Country, as well as a Horizons of everyone in the community to cultivate a volunteer, the Co-President of AWARE, and culture of growth by celebrating the diver- a HOTH board member. In her final year sity of perspectives in the community. on the Hill, she is determined to create an In his own words: “I want to be the environment, where each and every member middleman between the Students and the of the school community feels accepted. Administration. I want to share the new In her own words: “The past year has perspective that we have all established dur- posed a number of difficulties, and it is ing the pandemic, and use it for the better. hard to adapt, but we should take this as an I want to UNITE the NEW school com- opportunity to teach our community and munity." continue to make it our Westminster." Priscilla Ameyaw is a Sung Min Cho is a Margot Douglass is a boarder from Ghana. -

Tetrarch Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TETRARCH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ian Irvine | 704 pages | 05 Feb 2004 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9781841491998 | English | London, United Kingdom Tetrarch PDF Book Chapter Master Aetheon of the 19th Chapter of the Ultramarines Legion was rumoured to be Guilliman's choice to take up the role of the newest Prince of Ultramar. Eleventh Captain of the Ultramarines Chapter. After linking up with the 8th Parachute Battalion in Bois de Bavent, they proceeded to assist with the British advance on Normandy, providing reconnaissance for the troops. Maxentius rival Caesar , 28 October ; Augustus , c. Year of the 6 Emperors Gordian dynasty — Illyrian emperors — Gallic emperors — Britannic emperors — Cookie Policy. Keep scrolling for more. Luke Now in the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Cesar, Pontius Pilate being governor of Judea, and Herod being tetrarch of Galilee, and his brother In the summer of , Tetrarch got their first taste at extensive touring by doing a day east coast tour in support of the EP. D, Projector and Managing Editor. See idem. Galerius and Maxentius as Augusti of East and West. The four tetrarchs based themselves not at Rome but in other cities closer to the frontiers, mainly intended as headquarters for the defence of the empire against bordering rivals notably Sassanian Persia and barbarians mainly Germanic, and an unending sequence of nomadic or displaced tribes from the eastern steppes at the Rhine and Danube. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. Primarch of the Ultramarines Legion. The armor thickness was increased to a maximum of 16mm using riveted plating, and the Henry Meadows Ltd. -

Fall' of Rome

APOCALYPSE, TRANSFORMATION OR MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING? WESTERN SCHOLARSHIP AND THE ‘FALL’ OF ROME (1776-2008)1 Jeroen Wijnendaele In many ways the fifth century CE was one of the most remarkable centuries in European and Mediterranean History.2 An glance at a map of this region around 400 CE shows an empire stretching all the way from the Caucasus to the strait of Gibraltar and from the highlands in Scotland to the Red Sea. A Roman citizen living during the reign of Nero (54-68 CE) would still have recognised those borders as the same as those of his Empire. Yet looking further, around 500 CE, this empire has vanished in the West and been replaced by nearly a dozen barbarian kingdoms. The speed and magnitude of this geopolitical revolution is only comparable with twentieth century, when three empires that for centuries had dominated half of Europe were replaced with nearly twenty nation states. Despite its momentous impact on the shape of history, the fifth century has always been a bit of a black sheep in terms of scholarly attention. For most classicists it is too late, while for most medievalists too early. Furthermore, a lot of classicists feel hesitant to deal with this era. Only in the past few decades has there been a serious revaluation of this period. The old attitude is demonstrated by the original Cambridge Ancient History, the last volume of which stopped with the ascendancy of Constantine I in 324. In French, the period of the Later Roman Empire is usually called Le Bas-Empire—‘The Low Empire’. -

JUS- ONLINE ISSN 1827-7942 RIVISTA DI SCIENZE GIURIDICHE a Cura Della Facoltà Di Giurisprudenza Dell’Università Cattolica Di Milano

JUS- ONLINE ISSN 1827-7942 RIVISTA DI SCIENZE GIURIDICHE a cura della Facoltà di Giurisprudenza dell’Università Cattolica di Milano INDICE N. 3/2018 LUIGI BENVENUTI 2 Principio di sussidiarietà, diritti Sociali e welfare responsabile. Un confronto tra cultura sociologica e cultura giuridica MARCELLO CLARICH – BARBARA BOSCHETTI 28 Il Codice Terzo Settore: un nuovo paradigma ERNESTO BIANCHI 44 Evandro, Augusto. Auctoritas, potestas, imperium. Brevi annotazioni storiche e semantiche ANNAMARIA MANZO 57 Quinto Elio Tuberone e il suo tempo ANNA BELLODI ANSALONI 77 Il processo di Gesù: dalla flagellazione alla crocifissione ROSA GERACI 120 At the Borders of Religious Freedom: Proselytism between Law and Crime LEONARDO CAPRARA 143 Epikeia e legge naturale in Francisco Suárez PAWEŁ MALECHA 173 La riduzione di una chiesa a uso profano non sordido alla luce della normativa canonica vigente e delle sfide della Chiesa di oggi JusOnline n. 3/2018 ISSN 1827-7942 VP VITA E PENSIERO Luigi Benvenuti Professore ordinario di Diritto amministrativo, Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia Principio di sussidiarietà, diritti sociali e welfare responsabile. Un confronto tra cultura sociologica e cultura giuridica* SOMMARIO - 1. Premessa. - 2. Brevi riflessioni intorno ai concetti di sussidiarietà orizzontale e amministrazione condivisa. - 3. La giustiziabilità dei diritti sociali tra prassi e teoria. - 4. Segue: Il mondo dei diritti e il ruolo della giurisdizione. - 5. Il paradigma dello sperimentalismo democratico. - 6. L’Unione Europea come ordinamento composito. - 7. La prospettiva globale. - 8. Per un Welfare responsabile. - 9. Soggetto e persona nel dispositivo biopolitico. - 10. Welfare responsabile e cultura giuridica. - 11. Una appendice in tema di sanità. - 12. Conclusioni. 1. -

Julius Caesar

Working Paper CEsA CSG 168/2018 ANCIENT ROMAN POLITICS – JULIUS CAESAR Maria SOUSA GALITO Abstract Julius Caesar (JC) survived two civil wars: first, leaded by Cornelius Sulla and Gaius Marius; and second by himself and Pompeius Magnus. Until he was stabbed to death, at a senate session, in the Ides of March of 44 BC. JC has always been loved or hated, since he was alive and throughout History. He was a war hero, as many others. He was a patrician, among many. He was a roman Dictator, but not the only one. So what did he do exactly to get all this attention? Why did he stand out so much from the crowd? What did he represent? JC was a front-runner of his time, not a modern leader of the XXI century; and there are things not accepted today that were considered courageous or even extraordinary achievements back then. This text tries to explain why it’s important to focus on the man; on his life achievements before becoming the most powerful man in Rome; and why he stood out from every other man. Keywords Caesar, Politics, Military, Religion, Assassination. Sumário Júlio César (JC) sobreviveu a duas guerras civis: primeiro, lideradas por Cornélio Sula e Caio Mário; e depois por ele e Pompeius Magnus. Até ser esfaqueado numa sessão do senado nos Idos de Março de 44 AC. JC foi sempre amado ou odiado, quando ainda era vivo e ao longo da História. Ele foi um herói de guerra, como outros. Ele era um patrício, entre muitos. Ele foi um ditador romano, mas não o único. -

Establishing Roman Rule in Egypt: the Trilingual Stela of C

Originalveröffentlichung in: Katja Lembke, Martina Minas-Nerpel, Stefan Pfeiffer (Hg.), Tradition and Transformation: Egypt under Roman Rule; proceedings of the International Conference, Hildesheim, Roemer- and Plizaeus-Museum, 3–6 July 2008, Leiden ; Boston 2010, S. 265-298 ESTABLISHING ROMAN RULE IN EGYPT: THE TRILINGUAL STELA OF C. CORNELIUS GALLUS FROM PHILAE Martina Minas-Nerpel Stefan Pfeiffer Introduction When Octavian departed Egypt in 30 BC, he placed C. Cornelius Gallus, an eques by rank, in charge of the new Roman province Aegyptus. Gallus, who was responsible to Octavian himself, received the newly created title of praefectus Alexandreae et Aegypti, Prefect of Alexandria and Egypt. Soon enough, not even three years after his appointment, Gallus incurred the emperor ’s utter displeasure. The prefect was dismissed by Augustus, returned to Rome, was convicted by the Senate and fore stalled the impending banishment by committing suicide in 26 BC, as we are informed by Cassius Dio. 1 Gallus ’ alleged hubris and his assumed damnatio memoriae have much been discussed among ancient historians, papyrologists, and Egyptologists. In this respect, the most important and crucial Egyptian document is a trilingual inscription —hieroglyphic Egyptian, Latin, and Greek—dated to 16 April 29 BC (Fig. 1-5). It was carved on a stela re-discovered in 1896 in front of Augustus ’ temple at Philae (Fig. 6),2 which the prefect Rubius Barbarus had dedicated in Augustus ’ year 18 (13/12 BC).3 Cut into two parts, the stela had been reused in the foun dations, presumably of the temple ’s altar. The victory stela of pink Aswan granite, originally about 165 cm high, now 152 cm by 108 cm, is housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (CG 9295). -

ROMAN JURISTS and the CRISIS of the THIRD CENTURY A.D. in the ROMAN EMPIRE by LUKAS DE BLOIS

ROMAN JURISTS AND THE CRISIS OF THE THIRD CENTURY A.D. IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE By LUKAS DE BLOIS In this paper I would like to discuss the following questions: did the crisis of the third century A.D. in the Roman Empire finish the strong position of jurists and juridically skilled bureaucrats at the Roman imperial court? Did this crisis usher in the end oftheir scholarly production? The period ofthe Severan dynasty, which preceded the Third Century crisis, has always been regarded as the great age of juridically trained administrators, when Rome's most noted jurists of all time, all of them equites. were appointed to important posts and dominated the imperial council. At least three of them, Papinian, Messius, and Ulpian, became praefecti praetorio'. Even though most of the praetorian prefects during the early third century were not lawyers, the influence of jurists was out of all proportion to their numbers and to the length of time during which they were praetorian prefects2• After about A.D. 240, however, original scholarly work of learned jurists almost vanished from the earth and military men took the lead in the imperial council and in other key positions. Why did this happen? Severan emperors regularly appointed two praetorian prefects, a military man next to a jurist or an administrator. This was just a matter of practical expediency, not a fixed system3• The jurists among the men they appointed belonged to a kind of learned group, within which the younger ones borrowed ideas from their predecessors and which produced books and treatises that have become classics' in Roman law. -

The Historical Background

APPENDIX THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND All dates are B. C. I 06 Birth of Pompey and Cicero. 100 Sixth consulate of Marius. Birth of Julius Caesar. Ca. 100: publication of Meleager's Garland. ca. 97 Birth of Lucretius. 91-89 Social or Marsic War: Rome v. Italian Allies. 89-85 First Mithridatic War. 88 Sulla's march on Rome. Flight of Marius. 88-83 Sulla in the east. 86 Seventh consulate and death of Marius. Athens sacked by Sulla. Mithridates defeated. ca. 84 Birth of Catullus. 83-82 Civil War. 82-79 Dictatorship of Sulla. 73-71 Slave-revolt of Spartacus. Crushed by Crassus and Pompey. 70 First consulate of Pompey and Crassus. Birth of Virgil (Oct. 15) at Andes near Mantua. Ca. 70: arrival at Rome of the Callimachean Parthenius of Nicaea. ca. 69 Birth of Gallus. 67 Defeat of pirates by Pompey. 66 Lex Manilia confers on Pompey the command against Mithridates. 66-63 Pompey in the east. 65 Birth of Horace at Venusia. 63 Consulate of Cicero. Catilinarian conspiracy. Pompey's settlement of the east. Birth of Octavian, later Augustus (63 B.C.-A.D. 14). 60 Formation of first triumvirate: Caesar, Pompey, Crassus. 59 First consulate of Caesar. Birth of Livy at Padua. 58-49 Caesar in Gaul. 56 Conference at Luca: triumvirate renewed. 55 Second consulate of Pompey and Crassus. Ca. 55: birth of Tibullus. 54 Crassus sets out for Parthia. Death of Julia, Caesar's daughter and Pompey's wife. Ca. 54: deaths of Catullus and Lucretius; publication of De Rerum Natura. Birth of Livy. -

Rome and the Cottians in the Western Alps Carolynn Roncaglia Santa Clara University, [email protected]

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Classics College of Arts & Sciences Fall 2013 Client prefects?: Rome and the Cottians in the Western Alps Carolynn Roncaglia Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/classics Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Carolynn Roncaglia. 2013. “Client prefects?: Rome and the Cottians in the Western Alps”. Phoenix 67 (3/4). Classical Association of Canada: 353–72. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7834/phoenix.67.3-4.0353. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classics by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLIENT PREFECTS?: ROME AND THE COTTIANS IN THE WESTERN ALPS Carolynn Roncaglia introduction When Augustus and the Romans conquered the central and western Alps at the end of the first century b.c.e., most of the newly subjugated regions were brought under direct Roman control. The central portion of the western Alps, however, was left in the hands of a native dynasty, the Cottians, where it remained until the reign of Nero over a half-century later. The Cottians thus serve as one of many examples of a form of indirect Roman rule, its “two-level monarchy,” wherein the rulers of smaller kingdoms governed as friends and allies of the Roman state in an asymmetrical power relationship with Rome.1 This article explores how a native dynasty like the Cottians presented and legitimized their relationship with Rome to a domestic audience. -

The Beasts of Revelation Why Study Revelation 12?

Class 3 The Great Red Dragon vs The Woman Part 2 The Beasts of Revelation Why Study Revelation 12? • It outlines dramatic, earth-quaking events of extreme importance in the divine plan, that would forever re-shape the course of history • It contains practical exhortation and warning for disciples living during those events and for disciples today • It explains how the “Man of Sin” of 2 Thess. 2 would be revealed • It is the source of false beliefs in Christendom The Dragon The Key Players The Woman The Man-Child The Great Red Dragon – Pagan Roman Empire • The Dragon shares many similar feature to that of Daniel’s 4th Beast (Symbolizing the Roman Empire) • The language is also used by both Peter & Paul to describe pagan Roman Empire – Compare Rev. 12:4,9,10 with 1 Pet. 5:8 & Eph. 6:8-9 • Dragon – Ezek. 29:3 – used initially of Egypt, later conquered by Roman Empire & used as symbol of R.E. • Serpent – Gen 3:15 – Pagan R.E. bruised Christ’s heel • Red = fiery – pagan generals carried fire ahead of them into battle as offering to the gods • 7 heads – location identified as Rome (Rev. 17:9-10) • Heads Crowned – (rather than 10 horns) Symbol of kingly or imperial dignity The Woman of Revelation 12 Woman: Representative of the Christian Community (both true & False) The Woman in Glory (12:1): • Clothed with the sun • Clothed with imperial favour • Moon under her feet • Pagan religious system under her subjection • Crown of 12 stars on head • Awarded political ascendancy and honour through her military achievements The Woman of Revelation 12 Rev 12:2,5 “And she being with child cried, travailing in birth, and pained to be delivered… “And she brought forth a man child, who was to rule all nations with a rod of iron…” • Christian community pregnant with iniquity (2 Cor.