The Second Tetrarchy and the Great Persecution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book I. Title XXVII. Concerning the Office of the Praetor Prefect Of

Book I. Title XXVII. Concerning the office of the Praetor Prefect of Africa and concerning the whole organization of that diocese. (De officio praefecti praetorio Africae et de omni eiusdem dioeceseos statu.) Headnote. Preliminary. For a better understanding of the following chapters in the Code, a brief outline of the organization of the Roman Empire may be given, but historical works will have to be consulted for greater details. The organization as contemplated in the Code was the one initiated by Diocletian and Constantine the Great in the latter part of the third and the beginning of the fourth century of the Christian era, and little need be said about the time previous to that. During the Republican period, Rome was governed mainly by two consuls, tow or more praetors (C. 1.39 and note), quaestors (financial officers and not to be confused with the imperial quaestor of the later period, mentioned at C. 1.30), aediles and a prefect of food supply. The provinces were governed by ex-consuls and ex- praetors sent to them by the Senate, and these governors, so sent, had their retinue of course. After the empire was established, the provinces were, for a time, divided into senatorial and imperial, the later consisting mainly of those in which an army was required. The senate continued to send out ex-consuls and ex-praetors, all called proconsuls, into the senatorial provinces. The proconsul was accompanied by a quaestor, who was a financial officer, and looked after the collection of the revenue, but who seems to have been largely subservient to the proconsul. -

RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian's “Great

ABSTRACT RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy. (Under the direction of Prof. S. Thomas Parker) In the year 303, the Roman Emperor Diocletian and the other members of the Tetrarchy launched a series of persecutions against Christians that is remembered as the most severe, widespread, and systematic persecution in the Church’s history. Around that time, the Tetrarchy also issued a rescript to the Pronconsul of Africa ordering similar persecutory actions against a religious group known as the Manichaeans. At first glance, the Tetrarchy’s actions appear to be the result of tensions between traditional classical paganism and religious groups that were not part of that system. However, when the status of Jewish populations in the Empire is examined, it becomes apparent that the Tetrarchy only persecuted Christians and Manichaeans. This thesis explores the relationship between the Tetrarchy and each of these three minority groups as it attempts to understand the Tetrarchy’s policies towards minority religions. In doing so, this thesis will discuss the relationship between the Roman state and minority religious groups in the era just before the Empire’s formal conversion to Christianity. It is only around certain moments in the various religions’ relationships with the state that the Tetrarchs order violence. Consequently, I argue that violence towards minority religions was a means by which the Roman state policed boundaries around its conceptions of Roman identity. © Copyright 2016 Carl Ross Rice All Rights Reserved Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy by Carl Ross Rice A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2016 APPROVED BY: ______________________________ _______________________________ S. -

Eunuchs in the East, Men in the West? 147

Eunuchs in the East, Men in the West? 147 Chapter 8 Eunuchs in the East, Men in the West? Dis/unity, Gender and Orientalism in the Fourth Century Shaun Tougher Introduction In the narrative of relations between East and West in the Roman Empire in the fourth century AD, the tensions between the eastern and western imperial courts at the end of the century loom large. The decision of Theodosius I to “split” the empire between his young sons Arcadius and Honorius (the teenage Arcadius in the east and the ten-year-old Honorius in the west) ushered in a period of intense hostility and competition between the courts, famously fo- cused on the figure of Stilicho.1 Stilicho, half-Vandal general and son-in-law of Theodosius I (Stilicho was married to Serena, Theodosius’ niece and adopted daughter), had been left as guardian of Honorius, but claimed guardianship of Arcadius too and concomitant authority over the east. In the political manoeu- vrings which followed the death of Theodosius I in 395, Stilicho was branded a public enemy by the eastern court. In the war of words between east and west a key figure was the (probably Alexandrian) poet Claudian, who acted as a ‘pro- pagandist’ (through panegyric and invective) for the western court, or rather Stilicho. Famously, Claudian wrote invectives on leading officials at the eastern court, namely Rufinus the praetorian prefect and Eutropius, the grand cham- berlain (praepositus sacri cubiculi), who was a eunuch. It is Claudian’s two at- tacks on Eutropius that are the inspiration and central focus of this paper which will examine the significance of the figure of the eunuch for the topic of the end of unity between east and west in the Roman Empire. -

Agorapicbk-15.Pdf

Excavations of the Athenian Agora Picture Book No. 1s Prepared by Fred S. Kleiner Photographs by Eugene Vanderpool, Jr. Produced by The Meriden Gravure Company, Meriden, Connecticut Cover design: Coins of Gela, L. Farsuleius Mensor, and Probus Title page: Athena on a coin of Roman Athens Greek and Roman Coins in the Athenian Agora AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 1975 1. The Agora in the 5th century B.C. HAMMER - PUNCH ~ u= REVERSE DIE FLAN - - OBVERSE - DIE ANVIL - 2. Ancient method of minting coins. Designs were cut into two dies and hammered into a flan to produce a coin. THEATHENIAN AGORA has been more or less continuously inhabited from prehistoric times until the present day. During the American excava- tions over 75,000 coins have been found, dating from the 6th century B.c., when coins were first used in Attica, to the 20th century after Christ. These coins provide a record of the kind of money used in the Athenian market place throughout the ages. Much of this money is Athenian, but the far-flung commercial and political contacts of Athens brought all kinds of foreign currency into the area. Other Greek cities as well as the Romans, Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Turks have left their coins behind for the modern excavators to discover. Most of the coins found in the excavations were lost and never recovered-stamped into the earth floor of the Agora, or dropped in wells, drains, or cisterns. Consequently, almost all the Agora coins are small change bronze or copper pieces. -

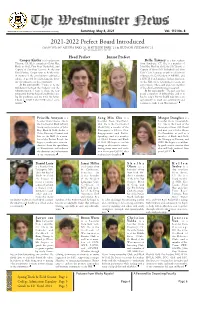

2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced - - - Times

Westminster School Simsbury, CT 06070 www.westminster-school.org Saturday, May 8, 2021 Vol. 110 No. 8 2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced COMPILED BY ALEYNA BAKI ‘21, MATTHEW PARK ‘21 & HUDSON STEDMAN ‘21 CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF, 2020-2021 Head Prefect Junior Prefect Cooper Kistler is a boarder from Bella Tawney is a day student Tiburon, CA. He is a member of John Hay, from Simsbury, CT. She is a member of Black & Gold, First Boys’ Basketball, and John Hay, Black & Gold, the SAC Board, a Captain of First Boys’ lacrosse. As the new Captain of First Girls’ Basketball and First Head Prefect, Cooper aims to be the voice Girls’ Cross Country, as well as a Horizons of everyone in the community to cultivate a volunteer, the Co-President of AWARE, and culture of growth by celebrating the diver- a HOTH board member. In her final year sity of perspectives in the community. on the Hill, she is determined to create an In his own words: “I want to be the environment, where each and every member middleman between the Students and the of the school community feels accepted. Administration. I want to share the new In her own words: “The past year has perspective that we have all established dur- posed a number of difficulties, and it is ing the pandemic, and use it for the better. hard to adapt, but we should take this as an I want to UNITE the NEW school com- opportunity to teach our community and munity." continue to make it our Westminster." Priscilla Ameyaw is a Sung Min Cho is a Margot Douglass is a boarder from Ghana. -

Rome of the Pilgrims and Pilgrimage to Rome

58 CHAPTER 2 Rome of the pilgrims and pilgrimage to Rome 2.1 Introduction As noted, the sacred topography of early Christian Rome focused on different sites: the official Constantinian foundations and the more private intra-mural churches, the tituli, often developed and enlarged under the patronage of wealthy Roman families or popes. A third, essential category is that of the extra- mural places of worship, almost always associated with catacombs or sites of martyrdom. It is these that will be examined here, with a particular attention paid to the documented interaction with Anglo-Saxon pilgrims, providing insight to their visual experience of Rome. The phenomenon of pilgrims and pilgrimage to Rome was caused and constantly influenced by the attitude of the early-Christian faithful and the Church hierarchies towards the cult of saints and martyrs. Rome became the focal point of this tendency for a number of reasons, not least of which was the actual presence of so many shrines of the Apostles and martyrs of the early Church. Also important was the architectural manipulation of these tombs, sepulchres and relics by the early popes: obviously and in the first place this was a direct consequence of the increasing number of pilgrims interested in visiting the sites, but it seems also to have been an act of intentional propaganda to focus attention on certain shrines, at least from the time of Pope Damasus (366-84).1 The topographic and architectonic centre of the mass of early Christian Rome kept shifting and moving, shaped by the needs of visitors and ‒ at the same time ‒ directing these same needs towards specific monuments; the monuments themselves were often built or renovated following a programme rich in liturgical and political sub-text. -

Tetrarch Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TETRARCH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ian Irvine | 704 pages | 05 Feb 2004 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9781841491998 | English | London, United Kingdom Tetrarch PDF Book Chapter Master Aetheon of the 19th Chapter of the Ultramarines Legion was rumoured to be Guilliman's choice to take up the role of the newest Prince of Ultramar. Eleventh Captain of the Ultramarines Chapter. After linking up with the 8th Parachute Battalion in Bois de Bavent, they proceeded to assist with the British advance on Normandy, providing reconnaissance for the troops. Maxentius rival Caesar , 28 October ; Augustus , c. Year of the 6 Emperors Gordian dynasty — Illyrian emperors — Gallic emperors — Britannic emperors — Cookie Policy. Keep scrolling for more. Luke Now in the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Cesar, Pontius Pilate being governor of Judea, and Herod being tetrarch of Galilee, and his brother In the summer of , Tetrarch got their first taste at extensive touring by doing a day east coast tour in support of the EP. D, Projector and Managing Editor. See idem. Galerius and Maxentius as Augusti of East and West. The four tetrarchs based themselves not at Rome but in other cities closer to the frontiers, mainly intended as headquarters for the defence of the empire against bordering rivals notably Sassanian Persia and barbarians mainly Germanic, and an unending sequence of nomadic or displaced tribes from the eastern steppes at the Rhine and Danube. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. Primarch of the Ultramarines Legion. The armor thickness was increased to a maximum of 16mm using riveted plating, and the Henry Meadows Ltd. -

The Developmentof Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrachs to The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. The Development of Early Imperial Dress from the Tetrarchs to the Herakleian Dynasty General Introduction The emperor, as head of state, was the most important and powerful individual in the land; his official portraits and to a lesser extent those of the empress were depicted throughout the realm. His image occurred most frequently on small items issued by government officials such as coins, market weights, seals, imperial standards, medallions displayed beside new consuls, and even on the inkwells of public officials. As a sign of their loyalty, his portrait sometimes appeared on the patches sown on his supporters’ garments, embossed on their shields and armour or even embellishing their jewelry. Among more expensive forms of art, the emperor’s portrait appeared in illuminated manuscripts, mosaics, and wall paintings such as murals and donor portraits. Several types of statues bore his likeness, including those worshiped as part of the imperial cult, examples erected by public 1 officials, and individual or family groupings placed in buildings, gardens and even harbours at the emperor’s personal expense. -

A BRIEF HISTORY of ANCIENT ROME a Timeline from 753 BC to 337 AD, Looking at the Successive Kings, Politicians, and Emperors Who Ruled Rome’S Expanding Empire

Rome: A Virtual Tour of the Ancient City A BRIEF HISTORY OF ANCIENT ROME A timeline from 753 BC to 337 AD, looking at the successive kings, politicians, and emperors who ruled Rome’s expanding empire. 21st April, Rome's Romulus and Remus featured in legends of Rome's foundation; 753 BC mythological surviving accounts, differing in details, were left by Dionysius of foundation Halicarnassus, Livy, and Plutarch. Romulus and Remus were twin sons of the war god Mars, suckled and looked-after by a she-wolf after being thrown in the river Tiber by their great-uncle Amulius, the usurping king of Alba Longa, and drifting ashore. Raised after that by the shepherd Faustulus and his wife, the boys grew strong and were leaders of many daring adventures. Together they rose against Amulius, killed him, and founded their own city. They quarrelled over its site: Romulus killed Remus (who had preferred the Aventine) and founded his city, Rome, on the Palatine Hill. 753 – Reign of Kings From the reign of Romulus there were six subsequent kings from the 509 BC 8th until the mid-6th century BC. These kings are almost certainly legendary, but accounts of their reigns might contain broad historical truths. Roman monarchs were served by an advisory senate, but held supreme judicial, military, executive, and priestly power. The last king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, was overthrown and a republican constitution installed in his place. Ever afterwards Romans were suspicious of kingly authority - a fact that the later emperors had to bear in mind. 509 BC Formation of Tarquinius Superbus, the last king was expelled in 509 BC. -

The Sanctoral Calendar of Wilhelm Loehe's Martyrologium Trans

The Sanctoral Calendar of Wilhelm Loehe's Martyrologium trans. with an introduction by Benjamin T. G. Mayes October 2001 Source: Wilhelm Loehe, Martyrologium. Zur Erklärung der herkömmlichen Kalendernamen. (Nürnberg: Verlag von Gottfr. Löhe, 1868). Introduction. Loehe's Martyrologium of 1868 was not his first attempt at a Lutheran sanctoral calendar. Already in 1859, he had his Haus-, Schul- und Kirchenbuch für Christen des lutherischen Bekenntnisses printed, in which he included a sanctoral calendar which was different in many ways from his later, corrected version. The earlier calendar contained many more names, normally at least two names per day. Major feasts were labelled with their Latin names. But the earlier calendar also had errors. Many dates were marked with a question mark. A comparison of the two calendars shows that in the earlier calendar, Loehe had mistaken Cyprian the Sorcerer (Sept. 26) with Cyprian of Carthage. On the old calendar's April 13th, Hermenegild was a princess. In the new one, he's a prince. In the earlier calendar, Hildegard the Abbess (Sept. 17) was dated in the 300's. In the new one, she is dated 1179. In fact, in the later calendar, I would suppose that half of the dates have been changed. Loehe was conscious of the limitations of his calendar. He realized especially how difficult the selection of names was. His calendar contains the names of many Bavarian saints. This is to be expected, considering the fact that his parish, Neuendettelsau, is located in Bavaria. Loehe gave other reasons for the selection of names in his Martyrologium: "The booklet follows the old calendar names. -

Roman Republic to Roman Empire

Roman Republic to Roman Empire Start of the Roman Revolution By the second century B.C., the Senate had become the real governing body of the Roman state. Members of the Senate were usually wealthy landowners, and they remained Senators for life. Rome’s government had started out as a Republic in which citizens elected people to represent them. But the Senate was filled with wealthy aristocrats who were not elected. Rome was slowly turning into an aristocracy, and the majority of middle and lower class citizens began to resent it. Land was usually at the center of class struggles in Rome. The wealthy owned most of the land while the farmers had found themselves unable to compete financially with the wealthy landowners and had lost most of their lands. As a result, many of these small farmers drifted to the cities, especially Rome, forming a large class of landless poor. Changes in the Roman army soon brought even worse problems. Starting around 100 B.C. the Roman Republic was struggling in several areas. The first was the area of expansion. The territory of Rome was expanding quickly and the republic form of government could not make decisions and create stability for the new territories. The second major struggle was that due to expansion, the Republic was also experiencing problems with collecting taxes from its citizens. The larger area of the growing Roman territory created difficulties with collecting taxes from a larger population. Government officials had to go to each town, this would take several months to reach the whole extent of Roman territory. -

![The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol. 3 [1776]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2938/the-history-of-the-decline-and-fall-of-the-roman-empire-vol-3-1776-1172938.webp)

The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol. 3 [1776]

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, vol. 3 [1776] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected].