The Syntax and Phonetics of Hiberno-English Dialects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Language: Did You Know?

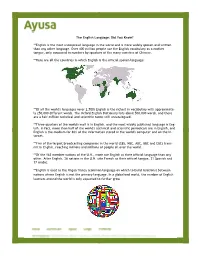

The English Language: Did You Know? **English is the most widespread language in the world and is more widely spoken and written than any other language. Over 400 million people use the English vocabulary as a mother tongue, only surpassed in numbers by speakers of the many varieties of Chinese. **Here are all the countries in which English is the official spoken language: **Of all the world's languages (over 2,700) English is the richest in vocabulary with approximate- ly 250,000 different words. The Oxford English Dictionary lists about 500,000 words, and there are a half-million technical and scientific terms still uncatalogued. **Three-quarters of the world's mail is in English, and the most widely published language is Eng- lish. In fact, more than half of the world's technical and scientific periodicals are in English, and English is the medium for 80% of the information stored in the world's computer and on the In- ternet. **Five of the largest broadcasting companies in the world (CBS, NBC, ABC, BBC and CBC) trans- mit in English, reaching millions and millions of people all over the world. **Of the 163 member nations of the U.N., more use English as their official language than any other. After English, 26 nations in the U.N. cite French as their official tongue, 21 Spanish and 17 Arabic. **English is used as the lingua franca (common language on which to build relations) between nations where English is not the primary language. In a globalized world, the number of English learners around the world is only expected to further grow. -

Old English: 450 - 1150 18 August 2013

Chapter 4 Old English: 450 - 1150 18 August 2013 As discussed in Chapter 1, the English language had its start around 449, when Germanic tribes came to England and settled there. Initially, the native Celtic inhabitants and newcomers presumably lived side-by-side and the Germanic speakers adopted some linguistic features from the original inhabitants. During this period, there is Latin influence as well, mainly through missionaries from Rome and Ireland. The existing evidence about the nature of Old English comes from a collection of texts from a variety of regions: some are preserved on stone and wood monuments, others in manuscript form. The current chapter focusses on the characteristics of Old English. In section 1, we examine some of the written sources in Old English, look at some special spelling symbols, and try to read the runic alphabet that was sometimes used. In section 2, we consider (and listen to) the sounds of Old English. In sections 3, 4, and 5, we discuss some Old English grammar. Its most salient feature is the system of endings on nouns and verbs, i.e. its synthetic nature. Old English vocabulary is very interesting and creative, as section 6 shows. Dialects are discussed briefly in section 7 and the chapter will conclude with several well-known Old English texts to be read and analyzed. 1 Sources and spelling We can learn a great deal about Old English culture by reading Old English recipes, charms, riddles, descriptions of saints’ lives, and epics such as Beowulf. Most remaining texts in Old English are religious, legal, medical, or literary in nature. -

Answering Particles: Findings and Perspectives

ANSWERING PARTICLES: FINDINGS AND PERSPECTIVES Emilio Servidio ([email protected]) 1. ANSWERING SYSTEMS 1.1. Historical introduction It is not uncommon for descriptive or prescriptive grammars to observe that a given language follows certain regularities when answering a polar question. Linguistics, on the other hand, has seldom paid much attention to the topic until recent years. The forerunner, in this respect, is Pope (1973), who sketched a typology of polar answering systems that followed in the steps of recent typological efforts on related topics (Ultan 1969, Moravcsik 1971 on polar questions). In the last decade, on the other hand, contributions have appeared from two different strands of theoretical research, namely, the syntactic approach to ellipsis as deletion (Kramer & Rawlins 2010; Holmberg 2013, 2016) and the study of conversation dynamics (Farkas & Bruce 2010; Krifka 2013, 2015; Roelofsen & Farkas 2015). This contribution aims at offering a critical overview of the state of the art on the topic1. In the remainder of this section, a typological sketch of answering systems will be drawn, before moving on to the extant analyses in section 2. In section 3, recent experimental work will be discussed. Section 4 summarizes and concludes. 1.2. Basic typology This survey will mainly deal with polar answers, defined as responding moves that address and fully satisfy the discourse requirements of a polar question. A different but closely related topic is the one of replies, i.e., moves that respond to a statement. Together, these moves go under the name of responses2. One first piece of terminology is the distinction between short and long responses. -

56. Pragmatic Failure and Referential Ambiguity When Attorneys Ask Child Witnesses “Do You Know/Remember” Questions

University of Southern California Law From the SelectedWorks of Thomas D. Lyon December 19, 2016 56. Pragmatic Failure and Referential Ambiguity when Attorneys Ask Child Witnesses “Do You Know/Remember” Questions. Angela D. Evans, Brock University Stacia N. Stolzenberg, Arizona State University Thomas D. Lyon Available at: https://works.bepress.com/thomaslyon/139/ Psychology, Public Policy, and Law © 2017 American Psychological Association 2017, Vol. 23, No. 2, 191–199 1076-8971/17/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/law0000116 Pragmatic Failure and Referential Ambiguity When Attorneys Ask Child Witnesses “Do You Know/Remember” Questions Angela D. Evans Stacia N. Stolzenberg Brock University Arizona State University, Tempe Thomas D. Lyon University of Southern California “Do you know” and “Do you remember” (DYK/R) questions explicitly ask whether one knows or remembers some information while implicitly asking for that information. This study examined how 4- to 9-year-old (N ϭ 104) children testifying in child sexual abuse cases responded to DYK/R wh- (who, what, where, why, how, and which) and yes/no questions. When asked DYK/R questions containing an implicit wh- question requesting information, children often provided unelaborated “yes” responses. Attorneys’ follow-up questions suggested that children usually misunderstood the pragmatics of the questions. When DYK/R questions contained an implicit yes/no question, unelaborated “yes” or “no” responses could be responding to the explicit or the implicit questions resulting in referentially ambig- uous responses. Children often provided referentially ambiguous responses and attorneys usually failed to disambiguate children’s answers. Although pragmatic failure following DYK/R wh- questions de- creased with age, the likelihood of referential ambiguity following DYK/R yes/no questions did not. -

The Past, Present, and Future of English Dialects: Quantifying Convergence, Divergence, and Dynamic Equilibrium

Language Variation and Change, 22 (2010), 69–104. © Cambridge University Press, 2010 0954-3945/10 $16.00 doi:10.1017/S0954394510000013 The past, present, and future of English dialects: Quantifying convergence, divergence, and dynamic equilibrium WARREN M AGUIRE AND A PRIL M C M AHON University of Edinburgh P AUL H EGGARTY University of Cambridge D AN D EDIU Max-Planck-Institute for Psycholinguistics ABSTRACT This article reports on research which seeks to compare and measure the similarities between phonetic transcriptions in the analysis of relationships between varieties of English. It addresses the question of whether these varieties have been converging, diverging, or maintaining equilibrium as a result of endogenous and exogenous phonetic and phonological changes. We argue that it is only possible to identify such patterns of change by the simultaneous comparison of a wide range of varieties of a language across a data set that has not been specifically selected to highlight those changes that are believed to be important. Our analysis suggests that although there has been an obvious reduction in regional variation with the loss of traditional dialects of English and Scots, there has not been any significant convergence (or divergence) of regional accents of English in recent decades, despite the rapid spread of a number of features such as TH-fronting. THE PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE OF ENGLISH DIALECTS Trudgill (1990) made a distinction between Traditional and Mainstream dialects of English. Of the Traditional dialects, he stated (p. 5) that: They are most easily found, as far as England is concerned, in the more remote and peripheral rural areas of the country, although some urban areas of northern and western England still have many Traditional Dialect speakers. -

Origins of NZ English

Origins of NZ English There are three basic theories about the origins of New Zealand English, each with minor variants. Although they are usually presented as alternative theories, they are not necessarily incompatible. The theories are: • New Zealand English is a version of 19th century Cockney (lower-class London) speech; • New Zealand English is a version of Australian English; • New Zealand English developed independently from all other varieties from the mixture of accents and dialects that the Anglophone settlers in New Zealand brought with them. New Zealand as Cockney The idea that New Zealand English is Cockney English derives from the perceptions of English people. People not themselves from London hear some of the same pronunciations in New Zealand that they hear from lower-class Londoners. In particular, some of the vowel sounds are similar. So the vowel sound in a word like pat in both lower-class London English and in New Zealand English makes that word sound like pet to other English people. There is a joke in England that sex is what Londoners get their coal in. That is, the London pronunciation of sacks sounds like sex to other English people. The same joke would work with New Zealanders (and also with South Africans and with Australians, until very recently). Similarly, English people from outside London perceive both the London and the New Zealand versions of the word tie to be like their toy. But while there are undoubted similarities between lower-class London English and New Zealand (and South African and Australian) varieties of English, they are by no means identical. -

When to Start Receiving Retirement Benefits

2021 When to Start Receiving Retirement Benefits At Social Security, we’re often asked, “What’s the The following chart shows an example of how your best age to start receiving retirement benefits?” The monthly benefit increases if you delay when you start answer is that there’s not a single “best age” for receiving benefits. everyone and, ultimately, it’s your choice. The most important thing is to make an informed decision. Base Monthly Benefit Amounts Differ Based on the your decision about when to apply for benefits on Age You Decide to Start Receiving Benefits your individual and family circumstances. We hope This example assumes a benefit of $1,000 the following information will help you understand at a full retirement age of 66 and 10 months 1300 $1,253 how Social Security fits into your retirement decision. $1,173 $1,093 nt 1100 $1,013 ou $1,000 $944 $877 Am 900 Your decision is a personal one $811 $758 fit $708 Would it be better for you to start getting benefits ne 700 early with a smaller monthly amount for more years, y Be 500 or wait for a larger monthly payment over a shorter hl timeframe? The answer is personal and depends on nt several factors, such as your current cash needs, Mo your current health, and family longevity. Also, 0 consider if you plan to work in retirement and if you 62 63 64 65 66 66 and 67 68 69 70 have other sources of retirement income. You must 10 months also study your future financial needs and obligations, Age You Choose to Start Receiving Benefits and calculate your future Social Security benefit. -

'Ja-Nee. No, I'm Fine': a Note on YES and NO in South Africa 69

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 48, 2017, 67-86 doi: 10.5774/48-0-281 ‘Ja-nee. No, I'm fine’: A note on YES and NO in South Africa Theresa Biberauer Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, and General Linguistics Department, Stellenbosch University, South Africa E-mail: [email protected] Marie-Louise van Heukelum General Linguistics Department, Stellenbosch University, South Africa Email: [email protected] Lalia Duke General Linguistics Department, Stellenbosch University, South Africa Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper considers some unusual uses of NO and YES observed in South African English (SAE) and other languages spoken in South Africa. Our objective is to highlight the fundamentally speaker-hearer-oriented nature of many of these elements, and to offer a formal perspective on their use. We also aim to highlight the value of pursuing more detailed investigations of these and other perspectival elements employed in SAE and other languages spoken in South Africa. Keywords: negation, affirmation, speaker-hearer perspective, clause structure, pragmaticalisation 1. Introduction1 Our point of departure in this note is the peculiarity of South African English (SAE) illustrated in (1): (1) A: How are you? 1 This paper had its origins in a lively discussion, in which Johan Oosthuizen also participated, during the first author's 2017 Honours Syntax seminar. We thank the participants in that class and also the audience at SAMWOP 6, held in Stellenbosch (30 November - 3 December 2017) for their comments and questions on a paper with partly similar content, in particular Alex Andrason, Robyn Berghoff, Kate Huddlestone, Bastian Persohn, Johan Oosthuizen, Erin Pretorius, Kristina Riedel, Andrew van der Spuy, Tarald Taraldsen and Jochen Zeller. -

Standard Southern British English As Referee Design in Irish Radio Advertising

Joan O’Sullivan Standard Southern British English as referee design in Irish radio advertising Abstract: The exploitation of external as opposed to local language varieties in advertising can be associated with a history of colonization, the external variety being viewed as superior to the local (Bell 1991: 145). Although “Standard English” in terms of accent was never an exonormative model for speakers in Ireland (Hickey 2012), nevertheless Ireland’s history of colonization by Britain, together with the geographical proximity and close socio-political and sociocultural connections of the two countries makes the Irish context an interesting one in which to examine this phenomenon. This study looks at how and to what extent standard British Received Pronunciation (RP), now termed Standard Southern British English (SSBE) (see Hughes et al. 2012) as opposed to Irish English varieties is exploited in radio advertising in Ireland. The study is based on a quantitative and qualitative analysis of a corpus of ads broadcast on an Irish radio station in the years 1977, 1987, 1997 and 2007. The use of SSBE in the ads is examined in terms of referee design (Bell 1984) which has been found to be a useful concept in explaining variety choice in the advertising context and in “taking the ideological temperature” of society (Vestergaard and Schroder 1985: 121). The analysis is based on Sussex’s (1989) advertisement components of Action and Comment, which relate to the genre of the discourse. Keywords: advertising, language variety, referee design, language ideology. 1 Introduction The use of language variety in the domain of advertising has received considerable attention during the past two decades (for example, Bell 1991; Lee 1992; Koslow et al. -

The Concept of Identity in the East Midlands of England NATALIE

The Concept of Identity in the East Midlands of England NATALIE BRABER Investigating feelings of identity in East Midlands adolescents Introduction When considering dialectal variation in the UK, linguists have frequently considered the North/South divide and the linguistic markers separating the two regions (see for example Trudgill, 1999; Wells, 1986). But it has been noted that this is not a straightforward division (e.g. Beal, 2008; Goodey, Gold, Duffett & Spencer, 1971; Montgomery, 2007; Wales, 2002). There are clear stereotypes for the North and South – but how do areas like the East Midlands fit into the picture? The boundaries between North and South are defined in different ways. Beal’s linguistic North does not include the East Midlands (Beal, 2008: 124- 5), neither does Wales’ (2002: 48). Trudgill states that in traditional dialectology the East Midlands area falls under ‘Central’ dialects, which come under the ‘Southern’ branch, but in modern dialectology it falls in the ‘North’. Hughes, Trudgill and Watt (2005: 70) contains a map which has the East Midlands in the North. Linguistically, the question has been raised whether there is a clear North/South boundary (see for example Upton (2012) where it is proposed that it is a transition zone). This paper revisits this question from the point of view of young people living in the East Midlands, to examine their sense of identity and whether this cultural divide is salient to them. The East Midlands is a problematic area in its definition geographically, and people may have difficulty in relating this to their own sense of identity. -

LANGUAGE VARIETY in ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England

LANGUAGE VARIETY IN ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England One thing that is important to very many English people is where they are from. For many of us, whatever happens to us in later life, and however much we move house or travel, the place where we grew up and spent our childhood and adolescence retains a special significance. Of course, this is not true of all of us. More often than in previous generations, families may move around the country, and there are increasing numbers of people who have had a nomadic childhood and are not really ‘from’ anywhere. But for a majority of English people, pride and interest in the area where they grew up is still a reality. The country is full of football supporters whose main concern is for the club of their childhood, even though they may now live hundreds of miles away. Local newspapers criss-cross the country in their thousands on their way to ‘exiles’ who have left their local areas. And at Christmas time the roads and railways are full of people returning to their native heath for the holiday period. Where we are from is thus an important part of our personal identity, and for many of us an important component of this local identity is the way we speak – our accent and dialect. Nearly all of us have regional features in the way we speak English, and are happy that this should be so, although of course there are upper-class people who have regionless accents, as well as people who for some reason wish to conceal their regional origins. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jana Krejčířová Australian English Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph. D. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph.D. for her patience and valuable advice. I would also like to thank my partner Martin Burian and my family for their support and understanding. Table of Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1. AUSTRALIA AND ITS HISTORY ................................................................. 10 1.1. Australia before the arrival of the British .................................................... 11 1.1.1. Aboriginal people .............................................................................. 11 1.1.2. First explorers .................................................................................... 14 1.2. Arrival of the British .................................................................................... 14 1.2.1. Convicts ............................................................................................. 15 1.3. Australia in the