Muzio Clementi and the British Musical Scene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

Keyboard Sonatas Nos. 87–92 Levon Avagyan, Piano Antonio Soler (1729–1783) Sonatas Included in Op

Antonio SOLER Keyboard Sonatas Nos. 87–92 Levon Avagyan, Piano Antonio Soler (1729–1783) sonatas included in Op. 4 bear the date 1779. These Sonata No. 92 in D major, numbered Op. 4, No. 2, is Keyboard Sonatas Nos. 87–92 sonatas follow classical procedure and are in several again in four movements and in a style that reflects its movements, although some of the movements had prior date, 1779, and contemporary styles and forms of Born in 1729 at Olot, Girona, Antonio Soler, like many Llave de la Modulación, a treatise explaining the art of existence as single-movement works. Sonata No. 91 in C composition, as well as newer developments in keyboard other Catalan musicians of his and later generations, had rapid modulation (‘modulación agitada’), which brought major starts with a movement that has no tempo marking, instruments. The Presto suggests similar influences – the his early musical training as a chorister at the great correspondence with Padre Martini in Bologna, the leading to a second movement, marked Allegro di molto, world of Haydn, Soler’s near contemporary. The third Benedictine monastery of Montserrat, where his teachers leading Italian composer and theorist, who vainly sought in which the bass makes considerable use of divided movement brings two minuets, the first Andante largo included the maestro di capilla Benito Esteve and the a portrait of Soler to add to his gallery of leading octaves. There is contrast in a short Andante maestoso, a and the second, which it frames, a sparer Allegro. The organist Benito Valls. Soler studied the work of earlier composers. -

CLEMENTI: Piano Concerto • Two Symphonies, Op

NAXOS NAXOS These four works are among the few surviving examples of Muzio Clementi’s early orchestral music. The two Symphonies, Op. 18 follow Classical models but are full of the surprise modulations and dynamic contrasts to be found in his piano sonatas. The Piano Concerto has a dazzling solo part and some delightful orchestral touches. Clementi’s Symphonies Nos. 1-4 can be heard on Naxos 8.573071 and 8.573112. CLEMENTI: DDD CLEMENTI: Muzio 8.573273 CLEMENTI Playing Time (1752-1832) 58:19 Piano Concerto in C major, Op. 33, No. 3 21:19 7 1 Allegro con spirito 9:30 Piano Concerto • Two Symphonies, Op. 18 Two Piano Concerto • Symphonies, Op. 18 Two Piano Concerto • 2 Adagio cantabile, con grande espressione 5:27 4 7 3 Presto 6:22 3 1 3 4 Minuetto pastorale in D major, WO 36 3:57 3 2 7 Symphony in B fl at major, Op. 18, No. 1 (1787) 16:27 3 5 Allegro assai 4:57 7 6 Un poco adagio 4:37 7 Minuetto (Allegretto) and Trio 4:05 9 www.naxos.com ൿ 8 Allegro assai 2:48 Made in Germany Commento in italiano all’interno Booklet Notes in English & Symphony in D major, Op. 18, No. 2 (1787) 16:36 Ꭿ 9 Grave – Allegro assai 5:49 2014 Naxos Rights US, Inc. 0 Andante 3:12 ! Minuetto (Un poco allegro) and Trio 3:19 @ Allegro assai 4:15 Bruno Canino, Piano Orchestra Sinfonica di Roma Francesco La Vecchia Recorded at the Auditorium di Via Conciliazione, Rome, 28th-29th October 2012 (tracks 1-3) and at the OSR 8.573273 Studios, Rome, 27th-30th December 2012 (tracks 4-12) • Producer: Fondazione Arts Academy 8.573273 Engineer and Editor: Giuseppe Silvi • Music Assistant: Desirée Scuccuglia • Booklet notes: Tommaso Manera Release editor: Peter Bromley • Cover: Paolo Zeccara • Publishers / Editions: Editori s.r.l., Albano Laziale, Rome (tracks 1-3, edited by Pietro Spada); Suvini Zerboni, Milan (track 4); Johann André, Offenbach am Main / Public Domain (tracks 5-8); Jean-Jérôme Imbault, Paris / Public Domain (tracks 9-12) 88.573273.573273 rrrr CClementilementi • 3_EU.indd3_EU.indd 1 119/05/149/05/14 112:022:02. -

Johann Nepomuk Hummel's Transcriptions

JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL´S TRANSCRIPTIONS OF BEETHOVEN´S SYMPHONY NO. 2, OP. 36: A COMPARISON OF THE SOLO PIANO AND THE PIANO QUARTET VERSIONS Aram Kim, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2012 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor Gustavo Romero, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Chair, Division of Keyboard Studies John Murphy, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kim, Aram. Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s Transcriptions of Beethoven´s Symphony No. 2, Op. 36: A Comparison of the Solo Piano and the Piano Quartet Versions. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2012, 30 pp., 2 figures, 13 musical examples, references, 19 titles. Johann Nepomuk Hummel was a noted Austrian composer and piano virtuoso who not only wrote substantially for the instrument, but also transcribed a series of important orchestral pieces. Among them are two transcriptions of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 36- the first a version for piano solo and the second a work for piano quartet, with flute substituting for the traditional viola part. This study will examine Hummel’s treatment of the symphony in both transcriptions, looking at a variety of pianistic devices in the solo piano version and his particular instrumentation choices in the quartet version. Each of these transcriptions can serve a particular purpose for performers. The solo piano version is an obvious virtuoso vehicle, whereas the quartet version can be a refreshing program alternative in a piano quartet concert. -

Composers and Publishers in Clementi's London

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Composers and publishers in Clementi’s London Book Section How to cite: Rowland, David (2018). Composers and publishers in Clementi’s London. In: Golding, Rosemary ed. The Music Profession in Britain, 1780-1920: New Perspectives on Status and Identity. Music in Nineteenth-Century Britain. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 32–52. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2018 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9781351965750/chapters/10.4324%2F9781315265001-3 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk 1 Composers and publishers in Clementi’s London David Rowland (The Open University) Clementi was in London by April 1775 and from then until shortly before his death in March 1832 he was involved with the capital’s music publishing industry, first as a composer, but also from 1798 as a partner in one of Europe’s largest and most important music-publishing firms.1 During the course of his career London’s music-publishing industry boomed and composers responded by producing regular streams of works tailored to the needs of a growing musical market. At the same time copyright law began to be clarified as it related music, a circumstance which significantly affected the relationship between composers and publishers. -

June 29 to July 5.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES June 29 - July 5, 2020 PLAY DATE : Mon, 06/29/2020 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto 6:11 AM Johann Nepomuk Hummel Serenade for Winds 6:31 AM Johan Helmich Roman Concerto for Violin and Strings 6:46 AM Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Symphony 7:02 AM Johann Georg Pisendel Concerto forViolin,Oboes,Horns & Strings 7:16 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Sonata No. 32 7:30 AM Jean-Marie Leclair Violin Concerto 7:48 AM Antonio Salieri La Veneziana (Chamber Symphony) 8:02 AM Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber Mensa sonora, Part III 8:12 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 34 8:36 AM Johannes Brahms Violin Sonata No. 3 9:05 AM Leroy Anderson Concerto for piano and orchestra 9:25 AM Arthur Foote Piano Quartet 9:54 AM Leroy Anderson Syncopated Clock 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem: Communio: Lux aeterna 10:06 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Violin Sonata No. 21, K 304/300c 10:23 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart DON GIOVANNI Selections 10:37 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Sonata for 2 pianos 10:59 AM Felix Mendelssohn String Quartet No. 3 11:36 AM Mauro Giuliani Guitar Concerto No. 1 12:00 PM Danny Elfman A Brass Thing 12:10 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Schwärmereien Concert Waltz 12:23 PM Franz Liszt Un Sospiro (A Sigh) 12:32 PM George Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue 12:48 PM John Philip Sousa Our Flirtations 1:00 PM Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony No. 6 1:43 PM Michael Kurek Sonata for Viola and Harp 2:01 PM Paul Dukas La plainte, au loin, du faune...(The 2:07 PM Leos Janacek Sinfonietta 2:33 PM Johannes Brahms Violin Sonata No. -

La Formació Musical Del Pare Antoni Soler · a Montserrat

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert LA FORMACIÓ MUSICAL DEL PARE ANTONI SOLER · A MONTSERRAT Gregori Estrada 85 El nom del pare Antoni Soler és ben conegut en el món musical d'avui. La difusió de la seva obra, difusió feta a través d'edicions, audicions i discos, presenta primordialment peces del repertori instrumental. No es pot dir encara que la figura d'Antoni Soler com a compositor sigui prou coneguda. la seva obra instrumental conservada i catalogada fins ara, és probablement inco11Jpleta. A més, Soler té una altra creació, la coral , que sobrepassa en el doble la quantitat de la instrumental. D'aquesta producció coral, avui només se n'han divulgat algunes peces, massa poques per poder-ne fer Un judici raonable. S'ha d'esperar que, amb els anys, el treball pacient dels investiga dors vagi posant en partitura intel·ligible les particel·les de cada una de les composicions corals sortides de la ploma d'Antoni Soler. El treball dels inves tigadors farà també possible una millor apreciació de l'obra de Soler a través de la interpretació viva de la seva música coral. Partitura i interpretació viva, dues condicions necessàries per poder aprofundir en el judici i la crítica dè l'obra de qualsevol compositor L'OBRA MUSICAL D'ANTONI SOLER L'obra musical del pare Soler és copiosa, cosa sorprenent si és té en compte que ell va morir prematurament als 54 anys. Com ja s'ha dit, la seva obra és coneguda sobretot en la part instrumental: més d'un centenar de Sonates per a instrument de tecla; algunes peces per a orgue; sis Concerts per a dos orgues; i sis Quintets per a corda i tecla. -

Grado Medio Prueba De Selección Piano 1º Curso

GRADO MEDIO PRUEBA DE SELECCIÓN PIANO 1º CURSO 1. EJERCICIOS TÉCNICOS. • 6 escalas y arpegios, en tonalidad mayor o/y menor 2. EJERCICIO DE LECTURA 1º VISTA. 3. OBRAS ORIENTATIVAS 1º CURSO. A) COMPOSITORES BARROCOS J. S. BACH Album Anna Magdalena Bach (Clavierbüchlein der Anna Magdalena Bach) Wiener Urtex Edition (editado por Naoyuki Taneda). Minueto en Sol BWV Anh.126 (Compositor desconocido) Marcha en Re BWV Anh. 122 (C. P. E. Bach) Polonesa en sol BWV Ahn. 125 (C. P. E. Bach) Marcha en Mi bemol BWV Ahn. 127 (C. P. E. Bach) Polonesa en Sol BWV Anh. 130 (J. A. Hasse) Apéndice: Suite de Clavecin en Sol (Christian Petzold) Pequeños Preludios: BWV 924, 926, 927, 930, 941, 942, 999, 933, 934. Invenciones: BWV 772 – 786, por ejemplo: No. 1 en Do, No. 4 en re. LOUIS CLAUDE DAQUIN Piezas para teclado Le Coucou (Rondeau) L ´Amusante (Rondeau) Mussette en Sol G. F. HÄNDEL Piezas para teclado. Aria en Sol HWV 441 Entrée en sol HWV 453.II (HHA IV/6) Lesson en la HWV 496 (HHA III/19) Minueto en sol HWV 434.IV (HHA II/1.4) Preludio en re HWV 564 (HHA IV/8) Toccata en sol HWV 586 (HHA IV/20) 1 1º CURSO HENRY PURCELL Piezas para teclado A Choice Collection of Lessons for the harpsichord or spinnet: Suites and Miscellaneuos : Una pieza que corresponda en extension mínima una página. JEAN PHILLIPE RAMEAU Pièces de Clavecin (1724) Tambourin (Rondeau) (de la Suite No. 2) La Villageoise (de la Suite No. 2) La Joyeuse (de la Suite No. -

Johann Nepomuk Hummel Piano Concerto Op

Johann Nepomuk Hummel (b. Bratislava, 14. November 1778 – d. Weimar, 17. Oktober 1837) Piano Concerto op.113 (1827) Beethoven’s VIP friend: Johann Nepomuk Hummel and his fifth Piano Concerto, op. 113 (1827) If there is one composer among Beethoven’s contemporaries that deserves to be better known and has – rightfully – received growing interest from performers and musicologists, then it is certainly Johann Nepomuk Hummel. Eight years Beethoven’s junior (born in 1778), Hummel was a child prodigy, he studied piano with Mozart and lived with the Mozart family for two years. He later succeeded Haydn as a Kapellmeister in Esterházy, and was the dedicatee of Schubert’s three last piano sonatas (D 958-960, 1828). He befriended Goethe and Beethoven, was a pall-bearer at the latter’s funeral, and played at his memorial concert. Indeed, there is no lack of celebrities and Very Important Composers in Hummel’s biography. More importantly, Hummel was a Very Important Pianist himself, boasting a reputation as one of the finest and most influential piano virtuosos of his generation. By the time he composed his Fifth Piano Concerto in 1827, the year of Beethoven’s death, Hummel was a firmly established authority as a piano virtuoso, teacher, and composer. Following Kapellmeister functions in Esterhazy (1804-11) and Stuttgart (1816-18), he was appointed at Weimar in 1819 and was to remain there until his death in 1837. His solid reputation was underpinned by his extensive touring career as a pianist and conductor, and by the publication of his own piano method, the Ausführlich theoretisch-practische Anweisung zum Piano-forte Spiel (Extensive theoretical and practical method of playing the pianoforte, 1828), an impressive tome of more than 450 pages dedicated to the Russian Emperor Nicolas I. -

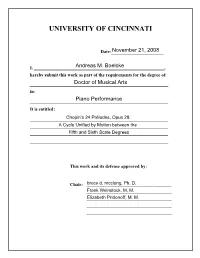

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Chopin’s 24 Préludes, Opus 28: A Cycle Unified by Motion between the Fifth and Sixth Scale Degrees A document submitted to the The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2008 by Andreas Boelcke B.A., Missouri Western State University in Saint Joseph, 2002 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2005 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, Ph.D. ii ABSTRACT Chopin’s twenty-four Préludes, Op. 28 stand out as revolutionary in history, for they are neither introductions to fugues, nor etude-like exercises as those preludes by other early nineteenth-century composers such as Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Johan Baptist Cramer, Friedrich Kalkbrenner, and Muzio Clementi. Instead they are the first instance of piano preludes as independent character pieces. This study shows, however, that Op. 28 is not just the beginning of the Romantic prelude tradition but forms a coherent large-scale composition unified by motion between the fifths and sixth scale degrees. After an overview of the compositional origins of Chopin’s Op. 28 and an outline of the history of keyboard preludes, the set will be compared to the contemporaneous ones by Hummel, Clementi, and Kalbrenner. The following chapter discusses previous theories of coherence in Chopin’s Préludes, including those by Jósef M. -

Program Notes | Friday, February 21, 2020

PROGRAM NOTES | FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 21, 2020 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN There is a transcription for piano and Born in Bonn, Germany, December 16, 1770 orchestra of the famous D Major Violin Died in Vienna, Austria, March 26, 1827 Concerto that Beethoven wrote out on a commission from Muzio Clementi’s The Five Beethoven Piano Concertos London publishing house, but this work is a at the Wichita Symphony Orchestra, curiosity done without much commitment February 21 and 23, 2020 from Beethoven. A couple of juvenilia By Don Reinhold, CEO, Wichita Symphony compositions exist mostly in fragments. There are even sketches from around 1816 The five piano concertos of Ludwig van of a first movement for what would have Beethoven are familiar works to regular been the sixth concerto, but Beethoven concertgoers. Even at a regional orchestra abandoned this work. such as Wichita’s, performances of all five as individual works would be typical over Following in Mozart’s footsteps, Beethoven a decade. Hearing them in chronological wrote his concertos as vehicles to display his sequence over a single weekend is rare keyboard virtuosity, which, as we’ll see, was and unusual, but appropriate this year accomplished up until his Fifth Concerto. It that marks the 250th anniversary of was only after “playing them around” a few Beethoven’s birth on December 16. While times for personal benefit that he sent them a few other orchestras will accomplish the off to publishers. feat this year with a single soloist or with five different soloists, Wichita is privileged Beethoven’s model and point of departure to enjoy performances by Stewart were the piano concertos of Mozart, Goodyear, regarded by many as one of especially those composed during Mozart’s today’s leading interpreters in the world of Viennese years, 1784 - 1791. -

Thomas Young and Eighteenth-Century Tempi Peter Pesic St

Performance Practice Review Volume 18 | Number 1 Article 2 Thomas Young and Eighteenth-Century Tempi Peter Pesic St. John's College, Santa Fe, New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Pesic, Peter (2013) "Thomas Young and Eighteenth-Century Tempi," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 18: No. 1, Article 2. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.201318.01.02 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol18/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Young and Eighteenth-Century Tempi Dedicated to the memory of Ralph Berkowitz (1910–2011), a great pianist, teacher, and master of tempo. The uthora would like to thank the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation for its support as well as Alexei Pesic for kindly photographing a rare copy of Crotch’s Specimens of Various Styles of Music. This article is available in Performance Practice Review: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol18/iss1/2 Thomas Young and Eighteenth-Century Tempi Peter Pesic In trying to determine musical tempi, we often lack exact and authoritative sources, especially from the eighteenth century, before composers began to indicate metronome markings. Accordingly, any independent accounts are of great value, such as were collected in Ralph Kirkpatrick’s pioneering article (1938) and most recently sur- veyed in this journal by Beverly Jerold (2012).1 This paper brings forward a new source in the writings of the English polymath Thomas Young (1773–1829), which has been overlooked by musicologists because its author’s best-known work was in other fields.