John Field's Piano Concerto No. 1.Pdf (6.285Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

1 Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D Minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion

1 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion "Ebarme dich, mein Gott" 3 George Frideric Handel Messiah: Hallelujah Chorus 4 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 41 C, K.551 "Jupiter" 5 Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings Op.11 6 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto A, K.622 7 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto 5 E-Flat, Op.73 "Emperor" (3) 8 Antonin Dvorak Symphony No 9 (IV) 9 George Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue (1924) 10 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem in D minor K 626 (aeternam/kyrie/lacrimosa) 11 George Frideric Handel Xerxes - Largo 12 Johann Sebastian Bach Toccata And Fugue In D Minor, BWV 565 (arr Stokowski) 13 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No 5 in C minor Op 67 (I) 14 Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite #3 BWV 1068: Air on the G String 15 Antonio Vivaldi Concerto Grosso in E Op. 8/1 RV 269 "Spring" 16 Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor 17 Edvard Grieg Peer Gynt 1, Op.46 18 Sergei Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor Op 18 (I) 19 Ralph Vaughan Williams Lark Ascending 20 Gustav Mahler Symphony 5 C-Sharp Min (4) 21 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky 1812 Overture 22 Jean Sibelius Finlandia, Op.26 23 Johann Pachelbel Canon in D 24 Carl Orff Carmina Burana: O Fortuna, In taberna, Tanz 25 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Serenade G, K.525 "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" 26 Johann Sebastian Bach Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D BWV 1050 (I) 27 Johann Strauss II Blue Danube Waltz, Op.314 28 Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Trio 39 G, Hob.15-25 29 George Frideric Handel Water Music Suite #2 in D 30 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Ave Verum Corpus, K.618 31 Johannes Brahms Symphony 1 C Min, Op.68 32 Felix Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Concert Program

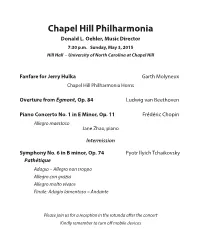

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Donald L. Oehler, Music Director 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 3, 2015 Hill Hall – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Garth Molyneux Chapel Hill Philharmonia Horns Overture from Egmont, Op. 84 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 11 Frédéric Chopin Allegro maestoso Jane Zhao, piano Intermission Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pathétique Adagio – Allegro non troppo Allegro con grazia Allegro molto vivace Finale: Adagio lamentoso – Andante Please join us for a reception in the rotunda after the concert Kindly remember to turn off mobile devices Pathétique The Romantic era idealized heroes. The works on tonight’s Chapel Hill Philharmonia program comprise three dis- tinct takes on heroism—the martyrdom of a leader to the cause of freedom, the creativity of an artist in the face of an incurable illness, and the passionate suffering of an individual descending into silence. Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Jaroslav Hulka, M.D., passed away on November 24, 2014, at age 84. A founding member of the CHP and long time principal French horn player, Jerry also served the orchestra as a board member and president. He is survived by his wife Barbara Sorenson Hulka, a UNC-Chapel Hill professor emerita and former CHP concertmaster. The couple met as undergraduates when both were section princi- pals in the Harvard/Radcliffe Orchestra. The Hulkas have donated generously to the CHP and to classical music programs at UNC- Chapel Hill and throughout the Triangle. In his “day job” Jerry was a well-respected academic and obstetrics/gynecology specialist, recognized as a wise physician, mentor, and innovator. -

A Senior Recital

Senior Recitals Recitals 4-7-2008 A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals Part of the Music Performance Commons Repository Citation Hansen, A. (2008). A Senior Recital. 1-1. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals/1 This Music Program is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Music Program in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Music Program has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Recitals by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. illi1YThe University Of Nevada Las Ve gas Co ll e~e of Fine Arts Ocparlmenl o f Music Pre:senls A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen, ptano ~Program~ ._a Conternplazione: Una Fantasia Piccola, Johann Nepomuk Hummel 1 Op. 107, No.3 (1778-1837) Deux Preludes Claude Achille Debussy Book 1, No.8: La fi/le aux cf7 eueux de /in (1862-1918) Book 2, No. 5: Bruyeres Ballades, Op. 10 Johannes Brahms No. 1 in D minor -Andante (1833-1897) No. 2 in D maj or -Andante No. 3 in B minor -Intermezzo No. 4 in B major - Andante con moto Papillons, Op. -

Rachmaninoff's Early Piano Works and the Traces of Chopin's Influence

Rachmaninoff’s Early Piano works and the Traces of Chopin’s Influence: The Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 & The Moments Musicaux, Op.16 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music by Sanghie Lee P.D., Indiana University, 2011 B.M., M.M., Yonsei University, Korea, 2007 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract This document examines two of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s early piano works, Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 (1892) and Moments Musicaux, Opus 16 (1896), as they relate to the piano works of Frédéric Chopin. The five short pieces that comprise Morceaux de Fantaisie and the six Moments Musicaux are reminiscent of many of Chopin’s piano works; even as the sets broadly build on his character genres such as the nocturne, barcarolle, etude, prelude, waltz, and berceuse, they also frequently are modeled on or reference specific Chopin pieces. This document identifies how Rachmaninoff’s sets specifically and generally show the influence of Chopin’s style and works, while exploring how Rachmaninoff used Chopin’s models to create and present his unique compositional identity. Through this investigation, performers can better understand Chopin’s influence on Rachmaninoff’s piano works, and therefore improve their interpretations of his music. ii Copyright © 2018 by Sanghie Lee All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements I cannot express my heartfelt gratitude enough to my dear teacher James Tocco, who gave me devoted guidance and inspirational teaching for years. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 THE COMPLETED SYMPHONIC COMPOSITIONS OF ALEXANDER ZEMLINSKY DISSERTATION Volume I Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert L. -

I Cannot Tell You More of This Arcadia Than That It Is at Present

This concert marked the the conclusion of our yearly Master class which offers to talented young musicians a week’s course performing on historic keyboard instruments in Tuscany, under the expert guidance of Professor Ella Sevskaya. The Master class began as a collaboration with the P. I. Tchaikovsky State Conservatory of Moscow, to facilitate the studies of Russian students who rarely have the opportunity of playing on historic instruments in their own country. In recent years we have extended the Masterclass to participants from other countries; this year we have one student from Japan, as well as five from Russia, who all have their origins in the Department of Historical and Contemporary Performance of the Moscow State Conservatory. Anastasia Akinfina, Sophia Gandilyan, Sergei Lukaschuk and Yulia Uspenskaya come to us directly from the Department, while Alexandra Nepomnyashchaya is a graduate ; she subsequently acquired a Master in harpsichord and in fortepiano at the Conservatory of Amsterdam, and is now undertaking a specialization in early keyboard at the Hochschule für Musik, Munich. Hanano Muratsubaki begins her study at the Music Department of the University of Augsburg this fall. The participants of our Masterclass worked this week in the Laboratorio di Restauro del Fortepiano of Florence, which kindly made available the fine fortepiano made in Vienna by Johann Schantz ca.1810-1815 which we hear in this evening’s recital. We are also grateful to the Accademia Bartolomeo Cristofori: amici del fortepiano, which kindly gave us access to their extraordinary collection of historic instruments. Ella Sevskaya was born in the Ukraine in 1961. -

Download Program Notes

Notes on the Program By James M. Keller, Program Annotator, The Leni and Peter May Chair Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun) Nocturnes Claude Debussy laude Debussy achieved his musical produced. This work is too exquisite, alas! It Cmaturity in the final decade of the 19th is too exquisite.” century, a magical moment in France when partisans of the visual arts fully embraced the gentle luster of Impressionism, poets navi- In Short gated the indirect locutions of Symbolism, Born: August 22, 1862, in Saint-Germain- composers struggled with the pluses and mi- en-Laye, just outside Paris, France nuses of Wagner, and the City of Light blazed Died: March 25, 1918, in Paris even more brightly than usual, enflamed with the pleasures of the Belle Époque. Works composed and premiered: Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune begun in 1892 — Several early Debussy masterpieces of perhaps as early as 1891 — and completed the 1890s have lodged in the repertoire, by October 23, 1894; premiered December 22, including, most strikingly, the Prélude à 1894, at a concert of the Société Nationale de l’après-midi d’un faune. Debussy was hardly Musique in Paris, Gustave Doret, conductor. a youngster when he composed it. He had Nocturnes composed 1897–99, drawing on begun studying at the Paris Conservatoire material sketched as early as 1892; dedicated to in 1872, when he was only ten; had served the music publisher Georges Hartmann; Nuages as resident pianist and musical pet for Na- and Fêtes premiered on December 9, 1900, dezhda von Meck, Tchaikovsky’s myste- at the Concerts Lamoureux in Paris, Camille rious patron, in Russia and on her travels Chevillard, conductor; the complete three- during the summers of 1880–82; had finally movement Noctunes was premiered on October 27, 1901, by the same orchestra and conductor. -

“Tragic” Mistake

UNDOING A “TRAGIC” MISTAKE DETERMINING THE INNER-MOVEMENT ORDER OF MAHLER’S SIXTH SYMPHONY A critical examination of the evidence by Jerry Bruck New York City October 19th, 2002 A publication of THE KAPLAN FOUNDATION 450 Park Avenue New York City © Jerry Bruck, 2002 I. OVERVIEW Nearly a century has passed since Gustav Mahler composed his Sixth Symphony, yet confusion still persists among conductors, scholars and biographers regarding the order of its inner movements. Mahler began work on the symphony in 1903, first composing a Scherzo and an Andante as the central pair of its eventual four-movement structure, framing them with the remaining movements the following year. He then reversed this “S-A” order of inner movements before the symphony’s premiere in 1906, and thereafter never reverted to their previous arrangement. It was not until 1919, almost a decade after Mahler’s death, that the conductor Willem Mengelberg queried Mahler’s widow about the order of these inner movements. Her response: “First Scherzo, then Andante” prompted him to alter the “A-S” order of his conductor’s score, igniting a controversy that has spanned the decades since. With the publication in 1963 of the first Critical Edition of the Sixth by the Internationale Gustav Mahler Gesellschaft (IGMG), the matter seemed settled at last. In his introduction, IGMG founder-editor Erwin Ratz stated that the thematic similarities between the symphony’s opening movement and its Scherzo, commented upon during rehearsals for its premiere, had prompted Mahler to succumb to the advice of “outside influences” to transpose the Sixth’s inner movements. -

Classic Choices April 6 - 12

CLASSIC CHOICES APRIL 6 - 12 PLAY DATE : Sun, 04/12/2020 6:07 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto No. 3 6:15 AM Georg Christoph Wagenseil Concerto for Harp, Two Violins and Cello 6:31 AM Guillaume de Machaut De toutes flours (Of all flowers) 6:39 AM Jean-Philippe Rameau Gavotte and 6 Doubles 6:47 AM Ludwig Van Beethoven Consecration of the House Overture 7:07 AM Louis-Nicolas Clerambault Trio Sonata 7:18 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento for Winds 7:31 AM John Hebden Concerto No. 2 7:40 AM Jan Vaclav Vorisek Sonata quasi una fantasia 8:07 AM Alessandro Marcello Oboe Concerto 8:19 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 70 8:38 AM Darius Milhaud Carnaval D'Aix Op 83b 9:11 AM Richard Strauss Der Rosenkavalier: Concert Suite 9:34 AM Max Reger Flute Serenade 9:55 AM Harold Arlen Last Night When We Were Young 10:08 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Exsultate, Jubilate (Motet) 10:25 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 3 10:35 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 10 (for two pianos) 11:02 AM Johannes Brahms Symphony No. 4 11:47 AM William Lawes Fantasia Suite No. 2 12:08 PM John Ireland Rhapsody 12:17 PM Heitor Villa-Lobos Amazonas (Symphonic Poem) 12:30 PM Allen Vizzutti Celebration 12:41 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Traumbild I, symphonic poem 12:55 PM Nino Rota Romeo & Juliet and La Strada Love 12:59 PM Max Bruch Symphony No. 1 1:29 PM Pr. Louis Ferdinand of Prussia Octet 2:08 PM Muzio Clementi Symphony No.