Franz Liszt's Early Weimar Period Piano Waltzes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schubert's!Voice!In!The!Symphonies!

! ! ! ! A!Search!for!Schubert’s!Voice!in!the!Symphonies! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Camille!Anne!Ramos9Klee! ! Submitted!to!the!Department!of!Music!of!Amherst!College!in!partial!fulfillment! of!the!requirements!for!the!degree!of!Bachelor!of!Arts!with!honors! ! Faculty!Advisor:!Klara!Moricz! April!16,!2012! ! ! ! ! ! In!Memory!of!Walter!“Doc”!Daniel!Marino!(191291999),! for!sharing!your!love!of!music!with!me!in!my!early!years!and!always!treating!me!like! one!of!your!own!grandchildren! ! ! ! ! ! ! Table!of!Contents! ! ! Introduction! Schubert,!Beethoven,!and!the!World!of!the!Sonata!! 2! ! ! ! Chapter!One! Student!Works! 10! ! ! ! Chapter!Two! The!Transitional!Symphonies! 37! ! ! ! Chapter!Three! Mature!Works! 63! ! ! ! Bibliography! 87! ! ! Acknowledgements! ! ! First!and!foremost!I!would!like!to!eXpress!my!immense!gratitude!to!my!advisor,! Klara!Moricz.!This!thesis!would!not!have!been!possible!without!your!patience!and! careful!guidance.!Your!support!has!allowed!me!to!become!a!better!writer,!and!I!am! forever!grateful.! To!the!professors!and!instructors!I!have!studied!with!during!my!years!at! Amherst:!Alison!Hale,!Graham!Hunt,!Jenny!Kallick,!Karen!Rosenak,!David!Schneider,! Mark!Swanson,!and!Eric!Wubbels.!The!lessons!I!have!learned!from!all!of!you!have! helped!shape!this!thesis.!Thank!you!for!giving!me!a!thorough!music!education!in!my! four!years!here!at!Amherst.! To!the!rest!of!the!Music!Department:!Thank!you!for!creating!a!warm,!open! environment!in!which!I!have!grown!as!both!a!student!and!musician.!! To!the!staff!of!the!Music!Library!at!the!University!of!Minnesota:!Thank!you!for! -

Homily 2Nd Sunday of Advent

Homily Bar 5: 1-9 Ps 126: 1-2, 2-3, 4-5, 6 2nd Sunday of Advent – C Phil 1: 4-6, 8-11 Rev. Peter G. Jankowski Lk 3: 1-6 December 8-9, 2018 The story I am about to share with you is entitled, The Cellist of Sarajevo and was written by Paul Sullivan for a periodical called Hope Magazine. This is the story… As a pianist, I was invited to perform with cellist Eugene Friesen at the International Cello Festival in Manchester, England. Every two years a group of the world’s greatest cellists and others devoted to that unassuming instrument – bow makers, collectors, historians – gather for a week of workshops, master classes, seminars, recitals and parties. Each evening the six hundred or so participants assemble for a concert. The opening-night performance at the Royal Northern College of Music consisted of works for unaccompanied cello. There on the stage in the magnificent concert hall was a solitary chair. No piano, no music stand, no conductor’s podium. This was to be cello music in its purest, most intense form. The atmosphere was supercharged with anticipation and concentration. The world-famous cellist Yo-Yo Ma was one of the performers that April night in 1994, and there was a moving story behind the musical composition he would play: On May 27, 1992, in Sarajevo, one of the few bakeries that still had a supply of flour was making and distributing bread to the starving, war-shattered people. At 4:00 p.m. a long line stretched into the street. -

Schubert's Mature Operas: an Analytical Study

Durham E-Theses Schubert's mature operas: an analytical study Bruce, Richard Douglas How to cite: Bruce, Richard Douglas (2003) Schubert's mature operas: an analytical study, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4050/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Schubert's Mature Operas: An Analytical Study Richard Douglas Bruce Submitted for the Degree of PhD October 2003 University of Durham Department of Music A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without their prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. 2 3 JUN 2004 Richard Bruce - Schubert's Mature Operas: An Analytical Study Submitted for the degree of Ph.D (2003) (Abstract) This thesis examines four of Franz Schubert's complete operas: Die Zwillingsbruder D.647, Alfonso und Estrella D.732, Die Verschworenen D.787, and Fierrabras D.796. -

December 3, 2006 2595Th Concert

For the convenience of concertgoers the Garden Cafe remains open until 6:00 pm. The use of cameras or recording equipment during the performance is not allowed. Please be sure that cell phones, pagers, and other electronic devices are turned off. Please note that late entry or reentry of The Sixty-fifth Season of the West Building after 6:30 pm is not permitted. The William Nelson Cromwell and F. Lammot Belin Concerts “Sixty-five, but not retiring” National Gallery of Art Music Department 2,595th Concert National Gallery of Art Sixth Street and Constitution Avenue nw Washington, DC Shaun Tirrell, pianist Mailing address 2000B South Club Drive Landover, md 20785 www.nga.gov December 3, 2006 Sunday Evening, 6:30 pm West Building, West Garden Court Admission free Program Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757) Sonata in F Minor, K. 466 (1738) Frederic Chopin (1810-1849) Ballade in F Major, op. 38 (1840) Franz Liszt (1811-1886) Funerailles (1849) Vallot d’Obtrmann (1855) INTERMISSION Sergey Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) Sonata no. 2 in B-flat Minor, op. 36 (1913) The Mason and Hamlin concert grand piano used in this performance Allegro agitato was provided by Piano Craft of Gaithersburg, Maryland. Lento Allegro molto The Musician Program Notes Shaun Tirrell is an internationally acclaimed pianist who has made his In this program, Shaun Tirrell shares with the National Gallery audience his home in the Washington, dc, area since 1995. A graduate of the Peabody skill in interpreting both baroque and romantic music. To represent the music Conservatory of Music in Baltimore, where he studied under Julian Martin of the early eighteenth-century masters of the harpsichord (the keyboard and earned a master of music degree and an artist diploma, he received a instrument of choice in that era), he has chosen a sonata by Domenico rave review in the Washington Post for his 1995 debut recital at the Kennedy Scarlatti. -

PROGRAM NOTES Franz Liszt Piano Concerto No. 2 in a Major

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Franz Liszt Born October 22, 1811, Raiding, Hungary. Died July 31, 1886, Bayreuth, Germany. Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Major Liszt composed this concerto in 1839 and revised it often, beginning in 1849. It was first performed on January 7, 1857, in Weimar, by Hans von Bronsart, with the composer conducting. The first American performance was given in Boston on October 5, 1870, by Anna Mehlig, with Theodore Thomas, who later founded the Chicago Symphony, conducting his own orchestra. The orchestra consists of three flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, cymbals, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-two minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Liszt’s Second Piano Concerto were given at the Auditorium Theatre on March 1 and 2, 1901, with Leopold Godowsky as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on March 19, 20, and 21, 2009, with Jean-Yves Thibaudet as soloist and Jaap van Zweden conducting. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on August 4, 1945, with Leon Fleisher as soloist and Leonard Bernstein conducting, and most recently on July 3, 1996, with Misha Dichter as soloist and Hermann Michael conducting. Liszt is music’s misunderstood genius. The greatest pianist of his time, he often has been caricatured as a mad, intemperate virtuoso and as a shameless and -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

CLEMENTI: Piano Concerto • Two Symphonies, Op

NAXOS NAXOS These four works are among the few surviving examples of Muzio Clementi’s early orchestral music. The two Symphonies, Op. 18 follow Classical models but are full of the surprise modulations and dynamic contrasts to be found in his piano sonatas. The Piano Concerto has a dazzling solo part and some delightful orchestral touches. Clementi’s Symphonies Nos. 1-4 can be heard on Naxos 8.573071 and 8.573112. CLEMENTI: DDD CLEMENTI: Muzio 8.573273 CLEMENTI Playing Time (1752-1832) 58:19 Piano Concerto in C major, Op. 33, No. 3 21:19 7 1 Allegro con spirito 9:30 Piano Concerto • Two Symphonies, Op. 18 Two Piano Concerto • Symphonies, Op. 18 Two Piano Concerto • 2 Adagio cantabile, con grande espressione 5:27 4 7 3 Presto 6:22 3 1 3 4 Minuetto pastorale in D major, WO 36 3:57 3 2 7 Symphony in B fl at major, Op. 18, No. 1 (1787) 16:27 3 5 Allegro assai 4:57 7 6 Un poco adagio 4:37 7 Minuetto (Allegretto) and Trio 4:05 9 www.naxos.com ൿ 8 Allegro assai 2:48 Made in Germany Commento in italiano all’interno Booklet Notes in English & Symphony in D major, Op. 18, No. 2 (1787) 16:36 Ꭿ 9 Grave – Allegro assai 5:49 2014 Naxos Rights US, Inc. 0 Andante 3:12 ! Minuetto (Un poco allegro) and Trio 3:19 @ Allegro assai 4:15 Bruno Canino, Piano Orchestra Sinfonica di Roma Francesco La Vecchia Recorded at the Auditorium di Via Conciliazione, Rome, 28th-29th October 2012 (tracks 1-3) and at the OSR 8.573273 Studios, Rome, 27th-30th December 2012 (tracks 4-12) • Producer: Fondazione Arts Academy 8.573273 Engineer and Editor: Giuseppe Silvi • Music Assistant: Desirée Scuccuglia • Booklet notes: Tommaso Manera Release editor: Peter Bromley • Cover: Paolo Zeccara • Publishers / Editions: Editori s.r.l., Albano Laziale, Rome (tracks 1-3, edited by Pietro Spada); Suvini Zerboni, Milan (track 4); Johann André, Offenbach am Main / Public Domain (tracks 5-8); Jean-Jérôme Imbault, Paris / Public Domain (tracks 9-12) 88.573273.573273 rrrr CClementilementi • 3_EU.indd3_EU.indd 1 119/05/149/05/14 112:022:02. -

Historie Der Rheinischen Musikschule Teil 1 Mit Einem Beitrag Von Professor Heinrich Lindlahr

Historie der Rheinischen Musikschule Teil 1 Mit einem Beitrag von Professor Heinrich Lindlahr Zur Geschichte des Musikschulwesens in Köln 1815 - 1925 Zu Beginn des musikfreundlichen 19. Jahrhunderts blieb es in Köln bei hochfliegenden Plänen und deren erfolgreicher Verhinderung. 1815, Köln zählte etwa fünfundzwanzigtausend Seelen, die soeben, wie die Bewohner der Rheinprovinz insgesamt, beim Wiener Kongreß an das Königreich Preußen gefallen waren, 1815 also hatte von Köln aus ein ungenannter Musikenthusiast für die Rheinmetropole eine Ausbildungsstätte nach dem Vorbild des Conservatoire de Paris gefordert. Sein Vorschlag erschien in der von Friedrich Rochlitz herausgegebenen führenden Allgemeinen musikalischen Zeitung zu Leipzig. Doch Aufrufe solcher Art verloren sich hierorts, obschon Ansätze zu einem brauchbaren Musikschulgebilde in Köln bereits bestanden hatten: einmal in Gestalt eines Konservatorienplanes, wie ihn der neue Maire der vormaligen Reichstadt, Herr von VVittgenstein, aus eingezogenen kirchlichen Stiftungen in Vorschlag gebracht hatte, vorwiegend aus Restklassen von Sing- und Kapellschulen an St. Gereon, an St. Aposteln, bei den Ursulinen und anderswo mehr, zum anderen in Gestalt von Heimkursen und Familienkonzerten, wie sie der seit dem Einzug der Franzosen, 1794, stellenlos gewordene Salzmüdder und Domkapellmeister Dr. jur. Bernhard Joseph Mäurer führte. Unklar blieb indessen, ob sich der Zusammenschluss zu einem Gesamtprojekt nach den Vorstellungen Dr. Mäurers oder des Herrn von Wittgenstein oder auch jenes Anonymus deshalb zerschlug, weil die Durchführung von Domkonzerten an Sonn- und Feiertagen kirchenfremden und besatzungsfreundlichen Lehrkräften hätte zufallen sollen, oder mehr noch deshalb, weil es nach wie vor ein nicht überschaubares Hindernisrennen rivalisierender Musikparteien gab, deren manche nach Privatabsichten berechnet werden müssten, wie es die Leipziger Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung von 1815 lakonisch zu kommentieren wusste. -

Johann Nepomuk Hummel's Transcriptions

JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL´S TRANSCRIPTIONS OF BEETHOVEN´S SYMPHONY NO. 2, OP. 36: A COMPARISON OF THE SOLO PIANO AND THE PIANO QUARTET VERSIONS Aram Kim, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2012 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor Gustavo Romero, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Chair, Division of Keyboard Studies John Murphy, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kim, Aram. Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s Transcriptions of Beethoven´s Symphony No. 2, Op. 36: A Comparison of the Solo Piano and the Piano Quartet Versions. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2012, 30 pp., 2 figures, 13 musical examples, references, 19 titles. Johann Nepomuk Hummel was a noted Austrian composer and piano virtuoso who not only wrote substantially for the instrument, but also transcribed a series of important orchestral pieces. Among them are two transcriptions of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 36- the first a version for piano solo and the second a work for piano quartet, with flute substituting for the traditional viola part. This study will examine Hummel’s treatment of the symphony in both transcriptions, looking at a variety of pianistic devices in the solo piano version and his particular instrumentation choices in the quartet version. Each of these transcriptions can serve a particular purpose for performers. The solo piano version is an obvious virtuoso vehicle, whereas the quartet version can be a refreshing program alternative in a piano quartet concert. -

UDC 786.2/781.68 Aisi the FIFTH PIANO CONCERTO by PROKOFIEV: COMPOSITINAL and PERFORMING INNOVATIONS

UDC 786.2/781.68 Aisi THE FIFTH PIANO CONCERTO BY PROKOFIEV: COMPOSITINAL AND PERFORMING INNOVATIONS The article is dedicated to considering compositional and performing innovations in the piano works of S. Prokofiev on the example of the fifth piano concerto. The phenomenon of the "new piano" in the context of piano instrumentalism, technique and technology of composition. It identifies the aspects of rethinking the romantic interpretation of the piano in favor of the natural-percussive. Keywords: piano concerto, instrumentalism, percussive nature of the piano, performing style. Prokofiev is one of the most outstanding composers-pianists of the XX century who boldly "exploded" both the canons of the composer’s and pianistic mastery of his time but managed to create his own coherent system of expressive means in both these areas of music. The five piano concertos by Prokofiev (created at the beginning and the middle of his career – 1912-1932) clearly reflect the most recognizable and the key for the composer's creativity artistic features of the author’s personality. Having dissociated himself in the strongest terms from the romantic tradition of the concert genre, Prokofiev created his new style – in terms of piano instrumentalism, technique and technology composition. All the five piano concertos "fit" just in the 20 years of Prokofiev’s life (after 1932 the composer did not write pianos, not counting begun in 1952 and unfinished double concert with the alleged dedication to S. Richter and A. Vedernikov). The first concert (1911-1912) – the most compact, light, known as "football" for expressed clarity of rhythm and percussion of the piano sound. -

Notes on the Music

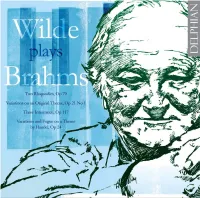

Notes on the music What are Brahms? This amusing gaffe may be But whatever your view you will surely see them, familiar but it ironically suggests a plurality and, in the words of the poet William Ritter, as ‘like in the case of the piano music, a panorama of the lustre of golden parks in autumn and the infinite richness and range. At the age of twenty austere black and white of winter walks’: a fitting Brahms introduced himself to Robert and Clara conclusion to an autobiographical journey of Schumann playing his piano sonatas and leaving exultant and reflective glory. them awed and enchanted by the sheer size and grandeur of his talent. For them he was But enough of generality. David Wilde’s richly already ‘fully armed’ and for Clara, in particular, a comprehensive programme opens with a young eagle had spread the wings of his genius. dramatic curtain-raiser – the two Rhapsodies The sonatas are, indeed, heroic utterances, Op 79, a notable return to Brahms’ Sturm und remembering Beethoven yet leaping into new Drang Romanticism. Here the terse opening realms of expression and an altogether novel of the B minor Rhapsody and its pleading, Romantic rhetoric. Such youthful outpouring was, Schumannesque second subject give us Brahms’ however, short-lived; Brahms turned gratefully old rhetorical sense of contrast, with an additional to variation form, finding the genre congenial to surprise in the form of a final dark-hued reworking his ever-growing mastery and imagination. of the central molto dolce expressivo’s chiming, bell-like counterpoints. The G minor Rhapsody is Throughout his life there would be temporary dominated by a powerful, arching melody and a returns to his early boldness, a memory no sombre triplet figure deployed with great ingenuity. -

The Pedagogical Legacy of Johann Nepomuk Hummel

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE PEDAGOGICAL LEGACY OF JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL. Jarl Olaf Hulbert, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006 Directed By: Professor Shelley G. Davis School of Music, Division of Musicology & Ethnomusicology Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837), a student of Mozart and Haydn, and colleague of Beethoven, made a spectacular ascent from child-prodigy to pianist- superstar. A composer with considerable output, he garnered enormous recognition as piano virtuoso and teacher. Acclaimed for his dazzling, beautifully clean, and elegant legato playing, his superb pedagogical skills made him a much sought after and highly paid teacher. This dissertation examines Hummel’s eminent role as piano pedagogue reassessing his legacy. Furthering previous research (e.g. Karl Benyovszky, Marion Barnum, Joel Sachs) with newly consulted archival material, this study focuses on the impact of Hummel on his students. Part One deals with Hummel’s biography and his seminal piano treatise, Ausführliche theoretisch-practische Anweisung zum Piano- Forte-Spiel, vom ersten Elementar-Unterrichte an, bis zur vollkommensten Ausbildung, 1828 (published in German, English, French, and Italian). Part Two discusses Hummel, the pedagogue; the impact on his star-students, notably Adolph Henselt, Ferdinand Hiller, and Sigismond Thalberg; his influence on musicians such as Chopin and Mendelssohn; and the spreading of his method throughout Europe and the US. Part Three deals with the precipitous decline of Hummel’s reputation, particularly after severe attacks by Robert Schumann. His recent resurgence as a musician of note is exemplified in a case study of the changes in the appreciation of the Septet in D Minor, one of Hummel’s most celebrated compositions.