Spectacles of Emancipation: Reading Rights Differently in India’S Legal Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

The Contest of Indian Secularism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto THE CONTEST OF INDIAN SECULARISM Erja Marjut Hänninen University of Helsinki Faculty of Social Sciences Political History Master’s thesis December 2002 Map of India I INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................1 PRESENTATION OF THE TOPIC ....................................................................................................................3 AIMS ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 SOURCES AND LITERATURE ......................................................................................................................7 CONCEPTS ............................................................................................................................................... 12 SECULARISM..............................................................................................................14 MODERNITY ............................................................................................................................................ 14 SECULARISM ........................................................................................................................................... 16 INDIAN SECULARISM .............................................................................................................................. -

Islamist Politics in South Asia After the Arab Spring: Parties and Their Proxies Working With—And Against—The State

RETHINKING POLITICAL ISLAM SERIES August 2015 Islamist politics in South Asia after the Arab Spring: Parties and their proxies working with—and against—the state WORKING PAPER Matthew J. Nelson, SOAS, University of London SUMMARY: Mainstream Islamist parties in Pakistan such as the Jama’at-e Islami and the Jamiat-e-Ulema-e-Islam have demonstrated a tendency to combine the gradualism of Brotherhood-style electoral politics with dawa (missionary) activities and, at times, support for proxy militancy. As a result, Pakistani Islamists wield significant ideological influence in Pakistan, even as their electoral success remains limited. About this Series: The Rethinking Political Islam series is an innovative effort to understand how the developments following the Arab uprisings have shaped—and in some cases altered—the strategies, agendas, and self-conceptions of Islamist movements throughout the Muslim world. The project engages scholars of political Islam through in-depth research and dialogue to provide a systematic, cross-country comparison of the trajectory of political Islam in 12 key countries: Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Syria, Jordan, Libya, Pakistan, as well as Malaysia and Indonesia. This is accomplished through three stages: A working paper for each country, produced by an author who has conducted on-the-ground research and engaged with the relevant Islamist actors. A reaction essay in which authors reflect on and respond to the other country cases. A final draft incorporating the insights gleaned from the months of dialogue and discussion. The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. -

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

Annualrepeng II.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT – 2007-2008 For about six decades the Directorate of Advertising and on key national sectors. Visual Publicity (DAVP) has been the primary multi-media advertising agency for the Govt. of India. It caters to the Important Activities communication needs of almost all Central ministries/ During the year, the important activities of DAVP departments and autonomous bodies and provides them included:- a single window cost effective service. It informs and educates the people, both rural and urban, about the (i) Announcement of New Advertisement Policy for nd Government’s policies and programmes and motivates print media effective from 2 October, 2007. them to participate in development activities, through the (ii) Designing and running a unique mobile train medium of advertising in press, electronic media, exhibition called ‘Azadi Express’, displaying 150 exhibitions and outdoor publicity tools. years of India’s history – from the first war of Independence in 1857 to present. DAVP reaches out to the people through different means of communication such as press advertisements, print (iii) Multi-media publicity campaign on Bharat Nirman. material, audio-visual programmes, outdoor publicity and (iv) A special table calendar to pay tribute to the exhibitions. Some of the major thrust areas of DAVP’s freedom fighters on the occasion of 150 years of advertising and publicity are national integration and India’s first war of Independence. communal harmony, rural development programmes, (v) Multimedia publicity campaign on Minority Rights health and family welfare, AIDS awareness, empowerment & special programme on Minority Development. of women, upliftment of girl child, consumer awareness, literacy, employment generation, income tax, defence, DAVP continued to digitalize its operations. -

Gender, Religion and Democratic Politics in India

UNRISD UNITED NATIONS RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT Gender, Religion and Democratic Politics in India Zoya Hasan Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India Final Research Report prepared for the project Religion, Politics and Gender Equality September 2009 The United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) is an autonomous agency engaging in multidisciplinary research on the social dimensions of contemporary devel- opment issues. Its work is guided by the conviction that, for effective development policies to be formulated, an understanding of the social and political context is crucial. The Institute attempts to provide governments, development agencies, grassroots organizations and scholars with a better understanding of how development policies and processes of economic, social and envi- ronmental change affect different social groups. Working through an extensive network of na- tional research centres, UNRISD aims to promote original research and strengthen research capacity in developing countries. UNRISD, Palais des Nations, 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland phone 41 (0)22 9173020; fax 41 (0)22 9170650; [email protected], www.unrisd.org The Heinrich Böll Foundation is a Green Think Tank that is part of an International Policy Net- work promoting ecology, democracy, and human rights worldwide. It is part of the Green politi- cal movement that has developed worldwide as a response to the traditional politics of social- ism, liberalism, and conservatism. Its main tenets are ecology and sustainability, democracy and human rights, self-determination and justice. It promotes gender democracy, meaning so- cial emancipation and equal rights for women and men, equal rights for cultural and ethnic mi- norities, societal and political participation of immigrants, non-violence and proactive peace poli- cies. -

Genre Channel Name Channel No Hindi Entertainment Star Bharat 114 Hindi Entertainment Investigation Discovery HD 136 Hindi Enter

Genre Channel Name Channel No Hindi Entertainment Star Bharat 114 Hindi Entertainment Investigation Discovery HD 136 Hindi Entertainment Big Magic 124 Hindi Entertainment Colors Rishtey 129 Hindi Entertainment STAR UTSAV 131 Hindi Entertainment Sony Pal 132 Hindi Entertainment Epic 138 Hindi Entertainment Zee Anmol 140 Hindi Entertainment DD National 148 Hindi Entertainment DD INDIA 150 Hindi Entertainment DD BHARATI 151 Infotainment DD KISAN 152 Hindi Movies Star Gold HD 206 Hindi Movies Zee Action 216 Hindi Movies Colors Cineplex 219 Hindi Movies Sony Wah 224 Hindi Movies STAR UTSAV MOVIES 225 Hindi Zee Anmol Cinema 228 Sports Star Sports 1 Hindi HD 282 Sports DD SPORTS 298 Hindi News ZEE NEWS 311 Hindi News AAJ TAK HD 314 Hindi News AAJ TAK 313 Hindi News NDTV India 317 Hindi News News18 India 318 Hindi News Zee Hindustan 319 Hindi News Tez 326 Hindi News ZEE BUSINESS 331 Hindi News News18 Rajasthan 335 Hindi News Zee Rajasthan News 336 Hindi News News18 UP UK 337 Hindi News News18 MP Chhattisgarh 341 Hindi News Zee MPCG 343 Hindi News Zee UP UK 351 Hindi News DD UP 400 Hindi News DD NEWS 401 Hindi News DD LOK SABHA 402 Hindi News DD RAJYA SABHA 403 Hindi News DD RAJASTHAN 404 Hindi News DD MP 405 Infotainment Gyan Darshan 442 Kids CARTOON NETWORK 449 Kids Pogo 451 Music MTV Beats 482 Music ETC 487 Music SONY MIX 491 Music Zing 501 Marathi DD SAHYADRI 548 Punjabi ZEE PUNJABI 562 Hindi News News18 Punjab Haryana Himachal 566 Punjabi DD PUNJABI 572 Gujrati DD Girnar 589 Oriya DD ORIYA 617 Urdu Zee Salaam 622 Urdu News18 Urdu 625 Urdu -

9 Post & Telecommunications

POST AND TELECOMMUNICATIONS 441 9 Post & Telecommunications ORGANISATION The Office of the Director General of Audit, Post and Telecommunications has a chequered history and can trace its origin to 1837 when it was known as the Office of the Accountant General, Posts and Telegraphs and continued with this designation till 1978. With the departmentalisation of accounts with effect from April 1976 the designation of AGP&T was changed to Director of Audit, P&T in 1979. From July 1990 onwards it was designated as Director General of Audit, Post and Telecommunications (DGAP&T). The Central Office which is the Headquarters of DGAP&T was located in Shimla till early 1970 and thereafter it shifted to Delhi. The Director General of Audit is assisted by two Group Officers in Central Office—one in charge of Administration and other in charge of the Report Group. However, there was a difficult period from November 1993 till end of 1996 when there was only one Deputy Director for the Central office. The P&T Audit Organisation has 16 branch Audit Offices across the country; while 10 of these (located at Chennai, Delhi, Hyderabad, Kapurthala, Lucknow, Mumbai, Nagpur, Patna and Thiruvananthapuram as well as the Stores, Workshop and Telegraph Check Office, Kolkata) were headed by IA&AS Officers of the rank of Director/ Dy. Director. The charges of the remaining branch Audit Offices (located at Ahmedabad, Bangalore, Bhopal, Cuttack, Jaipur and Kolkata) were held by Directors/ Dy. Directors of one of the other branch Audit Offices (as of March 2006) as additional charge. P&T Audit organisation deals with all the three principal streams of audit viz. -

Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Columbia University Academic Commons Competing Populisms: Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India Anuj Bhuwania Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2013 © 2013 Anuj Bhuwania All rights reserved ABSTRACT Competing Populisms: Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India Anuj Bhuwania This dissertation studies the politics of ‘Public Interest Litigation’ (PIL) in contemporary India. PIL is a unique jurisdiction initiated by the Indian Supreme Court in the aftermath of the Emergency of 1975-1977. Why did the Court’s response to the crisis of the Emergency period have to take the form of PIL? I locate the history of PIL in India’s postcolonial predicament, arguing that a Constitutional framework that mandated a statist agenda of social transformation provided the conditions of possibility for PIL to emerge. The post-Emergency era was the heyday of a new form of everyday politics that Partha Chatterjee has called ‘political society’. I argue that PIL in its initial phase emerged as its judicial counterpart, and was even characterized as ‘judicial populism’. However, PIL in its 21 st century avatar has emerged as a bulwark against the operations of political society, often used as a powerful weapon against the same subaltern classes whose interests were so loudly championed by the initial cases of PIL. In the last decade, for instance, PIL has enabled the Indian appellate courts to function as a slum demolition machine, and a most effective one at that – even more successful than the Emergency regime. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E796 HON. JOSÉ E. SERRANO HON. MIKE THOMPSON HON. DAN BURTON

E796 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks May 14, 2002 I am pleased to rise today to honor six he- continues to be an event of great significance. Mr. Spetzler also has provided vision and roic and dedicated men and women who re- This year, Bronx Borough President Adolfo leadership in the development of collabora- sponded to this call of greatness. These six in- Carrion, Jr. proudly proclaimed May 11, 2002 tions that support the health of rural commu- dividuals have dedicated their lives to helping as ‘‘Bronx Community College Hall of Fame nities at the local, state and national levels, in- others in need by working in the emergency 10K Race Day.’’ Each year, amateur and pro- cluding the California State Rural Health Asso- medical and ambulance services profession. fessional runners alike from all five of New ciation, Community Health Alliance, California Whenever we face a medical emergency, York’s boroughs and the entire tri-state area Primary Care Association and North Coast whether it is a family member, a friend or co- come together to run the Bronx. Participants Clinics Network. worker, the first thing we do is call for an am- include teams from municipal agencies along Mr. Spetzler has earned distinction as Presi- bulance. According to some estimates, there with faculty, staff and students of Bronx Com- dent of the Humboldt Child Care Council and are almost 960 million ambulance trips made munity College and other nearby schools. founder of the Northern California Rural each year in the United States. It is indeed one of the Bronx’s most antici- Round Table for Health Care Providers. -

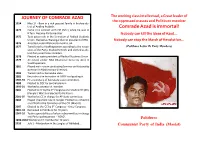

Comrade Azad Is Immortal! 1972 Came Into Contact with CPI (M-L) While He Was in B.Tech

JOURNEY OF COMRADE AZAD The working class intellectual, a Great leader of the oppressed masses and Politburo member 1954 May 14 - Born in a rich peasant family in Krishna dis- trict of Andhra Pradesh. Comrade Azad is immortal! 1972 Came into contact with CPI (M-L) while he was in B.Tech. Became Party member. Nobody can kill the ideas of Azad... 1975 Took active role in the formation of Radical Students Union. Elected as Warangal district president of RSU. Nobody can stop the March of Revolution… 1976 Arrested under MISA and 6 months Jail. 1977 Transferred to Visakhapatnam according to the neces- (Politburo Letter To Party Members) sities of the Party. Studied M.Tech. and elected as dis- trict Party committee member. 1978 Elected as state president of Radical Students Union. 1979 Arrested under NSA (National Security Act) in Visakhapatnam. 1981 Played main role in conducting Seminar on Nationality question in Madras (now Chennai). 1983 Transferred to Karnataka state. 1985 Key role in the formation of AIRSF and guiding it. 1987-93 First secretary of Karnataka state committee. 1990 Elected to COC by central plenum. 1995-01 Worked as secretariat member 2001 Elected to CC by the 9th Congress of erstwhile CPI (ML) [People's War] and elected to Politburo. 2001-07 Worked as CC in-charge for AP state committee. 2004 Played important role in merger. Elected to unified CC and PB after the formation of the CPI (Maoist). 2007 Elected to the CC by 9th Congress - Unity Congress 2001-10 Remained in Politburo for 10 years. 2007-10 Took responsibilities of urban subcommittee in-charge and Party spokesperson - 'AZAD'. -

Music, Art and Spirituality in Central Asia Program

Music, Art and Spirituality in Central Asia 29-30-31 October 2015 Island of San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice Program 29 October 9:00-10:00 registration and coffee 10:00-10:20 Institutional greetings 10:20 Chair Giovanni De Zorzi (DFBC, University Ca’ Foscari of Venice) Keynote. Jean During: Spiritual resonances in musical cultures of Central Asia: myths, dreams and ethics Session 1. Chair: Anna Contadini (SOAS, University of London) 11:30 From Bones to Beauty in Kyrgyz Felt Textiles Stephanie Bunn , University of St Andrews 12:10 The ‘tree of life’ motif in stucco mihrabs in the Zerafshan Valley Katherine Hughes , SOAS, University of London 12.50-14.30 lunch Session 2. Chair: Giovanni De Zorzi 14.30 Theory and Practice of Music under the Timurids Alexandre Papas , CNRS, Paris 15.10 Sufi Shrines and Maqām Traditions in Central Asia: the Uyghur On Ikki Muqam and the Kashmiri Sūfyāna Musīqī Rachel Harris , SOAS, University of London 15.50 A Musicological Study on Talqin as a Metric Cycle Shared by Spiritual and Secular-Classical Music Repertories in Central Asia Saeid Kordmafi , SOAS, University of London 16:30-16:50 coffee break Central Asian and Oriental Traces in Venice: a guided walk --- 30 October Session 3. Chair: Rachel Harris 9:30 Soviet Ballet and Opera: National Identity Building in Central Asia and the Caucasus Firuza Melville , University of Cambridge 10:10 Russianization and Colonial Knowledge of Traditional Musical Education in Turkestan (1865-1920). Inessa Kouteinikova , Amsterdam-St Petersburg-Tashkent 10:50-11:10 coffee break Session 4. Chair: Alexandre Papas 11:10 The legacy of the Central-Asian mystic Suleyman Baqirghani in the culture of the Volga Tatars: the phenomenon of the Baqirghan kitabı Guzel Sayfullina , Netherlands 11:50 Meetings with jâhrî dervishes in the Fergana Valley Giovanni De Zorzi , University Ca’ Foscari, Venice 12:30-14:00 lunch Session 5.