The Victims and Land Restitution Law in Colombia in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IFES Faqs on Elections in Colombia

Elections in Colombia 2018 Presidential Election Frequently Asked Questions Americas International Foundation for Electoral Systems 2011 Crystal Drive | Floor 10 | Arlington, VA 22202 | www.IFES.org May 14, 2018 Frequently Asked Questions When is Election Day? ................................................................................................................................... 1 Who are citizens voting for on Election Day? ............................................................................................... 1 When will the newly elected government take office? ................................................................................ 1 Who is eligible to vote?................................................................................................................................. 1 How many candidates are registered for the May 27 elections? ................................................................. 1 Who are the candidates? .............................................................................................................................. 1 How many registered voters are there? ....................................................................................................... 2 What is the structure of the government? ................................................................................................... 2 Are there any quotas in place? ..................................................................................................................... 3 What is the -

Transformaciones De La Radio En Colombia. Decretos Y Leyes Sobre

TRANSFORMACIONES DE LA RADIO EN COLOMBIA Decretos y leyes sobre la programación y su influencia en la construcción de una cultura de masas 1 Transformaciones de la radio en Colombia Director: José Ricardo Barrero Tapias María del Pilar Chaves Castro Monografía presentada como requisito parcial para optar por el título de Socióloga Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Facultad de Ciencias Sociales Bogotá, 2014 2 TRANSFORMACIONES DE LA RADIO EN COLOMBIA Decretos y leyes sobre la programación y su influencia en la construcción de una cultura de masas María del Pilar Chaves Castro Director: José Ricardo Barrero Tapias Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Facultad de Ciencias Sociales Departamento de sociología Bogotá, 2014 3 4 Contenido Introducción 8 1. EL PANORAMA RADIAL EN COLOMBIA ANTES DE 1948 13 1.1 Primeros años de la radio en el país 13 1.2 Colombia en relación con otros países de América Latina 15 1.3 Debates en torno a la programación 16 1.4 Primera legislación sobre la radio en Colombia 21 1.5 La Radiodifusora Nacional 23 2. 1948: LA RADIO COMO INCITADORA 27 2.1. Lo sucedido el 9 de abril de 1948 desde los micrófonos. 27 2.2. Cierres de emisoras 31 2.3. El decreto 1787 del 31 de mayo de 1948 32 2.4. Decreto 3384 del 29 de septiembre 1948 38 3. PANORAMA RADIAL EN COLOMBIA DESPUÉS DE 1948 41 3.1 Las cadenas radiales 41 3.1.1 Cadena Radial Colombiana (CARACOL) 42 3.1.2. Radio Cadena Nacional (RCN) 43 3.1.3 Cadena TODELAR 44 3.2. Radios culturales y educativas 44 3.2.1 La H.J.C.K., el mundo en Bogotá 45 3.2.2 Radio Sutatenza: la radio educadora 46 5 3.3 La censura en los gobiernos de Laureano Gómez y Rojas Pinilla 48 3.4 El decreto el 3418 de 1954 49 Conclusiones 51 Anexos 56 Referencias 67 Bibliografía 70 6 7 Introducción Los medios de comunicación en Colombia ocupan un espacio central en la cotidianidad de las personas. -

Redalyc.Institucionalización Organizativa Y Procesos De

Estudios Políticos ISSN: 0121-5167 [email protected] Instituto de Estudios Políticos Colombia Duque Daza, Javier Institucionalización organizativa y procesos de selección de candidatos presidenciales en los partidos Liberal y Conservador colombianos 1974-2006 Estudios Políticos, núm. 31, julio-diciembre, 2007 Instituto de Estudios Políticos Medellín, Colombia Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=16429059008 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Institucionalización organizativa y procesos de selección de candidatos presidenciales en los partidos Liberal y Conservador colombianos 1974-2006∗ Organizational Institutionalization and Selection Process of Presidential Candidates in the Liberal and Conservative colombian Parties Javier Duque Daza∗ Resumen: En este artículo se analizan los procesos de selección de los candidatos profesionales en los partidos Liberal y Conservador colombianos durante el periodo 1974-2006. A partir del enfoque de la institucionalización organizativa, el texto aborda las características de estos procesos a través de tres dimensiones analíticas: la existencia de reglas de juego, su grado de aplicación y acatamiento por parte de los actores internos de los partidos. El argumento central es que ambos partidos presentan un precario proceso de institucionalización organizativa, el cual se expresa en la debilidad de sus procesos de rutinización de las reglas internas. Finaliza mostrando cómo los sucedido en las elecciones de 2002 y de 2006, en las que se puso en evidencia que el predominio histórico de los partidos Liberal y Conservador estaba siendo disputado por nuevos partidos, los ha obligado a encaminarse hacia su reestructuración y hacia la búsqueda de mayores niveles de institucionalización organizativa. -

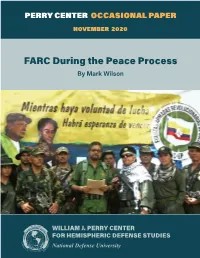

FARC During the Peace Process by Mark Wilson

PERRY CENTER OCCASIONAL PAPER NOVEMBER 2020 FARC During the Peace Process By Mark Wilson WILLIAM J. PERRY CENTER FOR HEMISPHERIC DEFENSE STUDIES National Defense University Cover photo caption: FARC leaders Iván Márquez (center) along with Jesús Santrich (wearing sunglasses) announce in August 2019 that they are abandoning the 2016 Peace Accords with the Colombian government and taking up arms again with other dissident factions. Photo credit: Dialogo Magazine, YouTube, and AFP. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and are not an official policy nor position of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense nor the U.S. Government. About the author: Mark is a postgraduate candidate in the MSc Conflict Studies program at the London School of Economics. He is a former William J. Perry Center intern, and the current editor of the London Conflict Review. His research interests include illicit networks as well as insurgent conflict in Colombia specifically and South America more broadly. Editor-in-Chief: Pat Paterson Layout Design: Viviana Edwards FARC During the Peace Process By Mark Wilson WILLIAM J. PERRY CENTER FOR HEMISPHERIC DEFENSE STUDIES PERRY CENTER OCCASIONAL PAPER NOVEMBER 2020 FARC During the Peace Process By Mark Wilson Introduction The 2016 Colombian Peace Deal marked the end of FARC’s formal military campaign. As a part of the demobilization process, 13,000 former militants surrendered their arms and returned to civilian life either in reintegration camps or among the general public.1 The organization’s leadership were granted immunity from extradition for their conduct during the internal armed conflict and some took the five Senate seats and five House of Representatives seats guaranteed by the peace deal.2 As an organiza- tion, FARC announced its transformation into a political party, the Fuerza Alternativa Revolucionaria del Común (FARC). -

La Variabilidad Climática Y El Cambio Climático En Colombia

LA VARIABILIDAD CLIMÁTICA Y EL CAMBIO CLIMÁTICO EN COLOMBIA Juan Manuel Santos Calderón Guillermo Eduardo Armenta Porras Presidente de la República de Colombia Xavier Corredor Llano María Alejandra Guerrero Morillo Luis Gilberto Murillo Zaida Yamile Peña Beltrán LA VARIABILIDAD Ministro de Ambiente y Desarrollo Germán AndrésTorres Soler Sostenible Bryan Esteban Bonilla Velázquez Danys Wilfredo Ortiz Olarte Carlos Alberto Botero López Nestor Ricardo Bernal Suarez CLIMÁTICA Y EL Viceministro de Ambiente y Desarrollo Xabier Lecanda García Sostenible Grupo de Investigación “Tiempo, clima y sociedad” Omar Franco Torres Departamento de Geografía - Facultad de CAMBIO CLIMÁTICO Director General Ciencias Humanas - UNAL Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales – IDEAM COMITÉ EDITORIAL EN COLOMBIA José Franklyn Ruiz Murcia Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Subdirector de Meteorología (E) - IDEAM Ambientales: Jeimmy Yanely Melo Franco, José Franklyn Ruiz Murcia. Ignacio Mantilla Prada Rector Universidad Nacional de Colombia: José Daniel Universidad Nacional de Colombia - UNAL Pabón Caicedo Jaime Franky Rodríguez Cítese como Vicerrector - UNAL Sede Bogotá IDEAM - UNAL, Variabilidad Climática y Cambio Luz Amparo Fajardo Uribe Climático en Colombia, Bogotá, D.C., 2018. Decana de la Facultad de Ciencias Humanas - UNAL Sede Bogotá 2018, Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales – IDEAM; Universidad José Daniel Pabón Caicedo Nacional de Colombia – UNAL. Todos los Director del Departamento de Geografía derechos reservados. Los textos pueden ser Facultad de Ciencias Humanas - UNAL usados parcial o totalmente citando la fuente. Su Sede Bogotá reproducción total o parcial debe ser autorizada por el IDEAM. AUTORES DEL DOCUMENTO Publicación aprobada por el IDEAM Marzo de Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y 2018, Bogotá D.C., Colombia - Estudios Ambientales - IDEAM Distribución Gratuita. -

Martinez V. Columbian Emeralds

For Publication IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE VIRGIN ISLANDS FRANKLIN MARTINEZ, ) S. Ct. Civ. No. 2007-06 ) S. Ct. Civ. No. 2007-11 Appellant/Plaintiff, ) Re: Super. Ct. Civ. No. 641-2000 ) v. ) ) COLOMBIAN EMERALDS, INC., ) ) Appellee/Defendant. ) ) On Appeal from the Superior Court of the Virgin Islands Argued: July 19, 2007 Filed: March 4, 2009 BEFORE: RHYS S. HODGE, Chief Justice; MARIA M. CABRET, Associate Justice; and IVE ARLINGTON SWAN, Associate Justice. APPEARANCES: Joseph B. Arellano, Esq. Arellano & Associates St. Thomas, U.S.V.I. Attorney for Appellant A. Jeffrey Weiss, Esq. A.J. Weiss & Associates St. Thomas, U.S.V.I. Attorney for Appellee OPINION OF THE COURT HODGE, Chief Justice. Appellant Franklin Martinez (“Martinez”) challenges the Superior Court’s order dismissing his complaint and ordering him to arbitration, and denying both his subsequent motion for reconsideration of the dismissal and his companion motion for stay of the proceedings pending arbitration. Martinez also challenges the award of attorney’s fees to Appellee Colombian Emeralds, Inc. (“CEI”). For the reasons stated below, the dismissal of the complaint and award of attorneys’ Martinez v. Colombian Emeralds, Inc. S. Ct. Civ. Nos. 2007-006 & 2007-011 Opinion of the Court Page 2 of 15 fees will be reversed. I. BACKGROUND Martinez, a citizen of Colombia and Switzerland, filed suit against CEI, a Virgin Islands corporation, alleging that he possessed an interest in certain real property located in St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, titled in CEI’s name. He sought an injunction to prevent CEI from selling the property or listing it for sale. -

Radiografía De La Adaptación Del Periódico El Espectador a La Era Digital

Radiografía de la adaptación del periódico El Espectador a la era digital Herramientas útiles para digitalizar un medio Laura Alejandra Moreno Urriaga Trabajo de Grado para optar por el título de Comunicadora Social Campo profesional Periodismo Director Juan Carlos Rincón Escalante Bogotá, junio de 2020 Reglamento de la Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Artículo 23 Resolución 13 de 1946: “La Universidad no se hace responsable por los conceptos emitidos por los alumnos en sus trabajos de grado, solo velará porque no se publique nada contrario al dogma y la moral católicos y porque el trabajo no contenga ataques y polémicas puramente personales, antes bien, se vean en ellas el anhelo de buscar la verdad y la justicia”. 2 Cajicá, junio 5 de 2020 Decana Marisol Cano Busquets Decana de la Facultad de Comunicación y Lenguaje Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Apreciada decana, Como estudiante de noveno semestre de la carrera de Comunicación social, me permito presentarle mi trabajo de grado titulado “Radiografía de la adaptación del periódico El Espectador a la era digital: Herramientas útiles para digitalizar un medio”, con el fin de optar al grado de comunicadora social con énfasis en periodismo. El trabajo consiste en el estudio de caso del periódico El Espectador y su transición al modelo de negocio de cobro por contenido digital. En él destaco las estrategias, modificaciones y decisiones que llevaron al medio a optar por este modelo de negocio, en un momento donde se desdibuja el modelo de sostenibilidad de la prensa tradicional soportado en la pauta publicitaria. Cordialmente, Laura Alejandra Moreno Urriaga C.C. 1070021549 3 Decana Marisol Cano Busquets Facultad de Comunicación Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Estimada decana: Me complace presentarle la tesis titulada “Radiografía de la adaptación del periódico El Espectador a la era digital: Herramientas útiles para digitalizar un medio”, presentada por la estudiante Laura Alejandra Moreno Urriaga para obtener el grado de Comunicadora Social. -

The Maritime Voyage of Jorge Juan to the Viceroyalty of Peru (1735-1746)

The Maritime Voyage of Jorge Juan to the Viceroyalty of Peru (1735-1746) Enrique Martínez-García — Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas* María Teresa Martínez-García — Kansas University** Translated into English (August 2012) One of the most famous scientific expeditions of the Enlightenment was carried out by a colorful group of French and Spanish scientists—including the new Spanish Navy lieutenants D. Jorge Juan y Santacilia (Novelda 1713-Madrid 1773) and D. Antonio de Ulloa y de la Torre-Giralt (Seville 1716-Isla de León 1795)—at the Royal Audience of Quito in the Viceroyalty of Peru between 1736 and 1744. There, the expedition conducted geodesic and astronomical observations to calculate a meridian arc associated with a degree in the Equator and to determine the shape of the Earth. The Royal Academy of Sciences of Paris, immersed in the debate between Cartesians (according to whom the earth was a spheroid elongated along the axis of rotation (as a "melon")) and Newtonians (for whom it was a spheroid flattened at the poles (as a "watermelon")), decided to resolve this dispute by comparing an arc measured near the Equator (in the Viceroyalty of Peru, present-day Ecuador) with another measured near the North Pole (in Lapland). The expedition to the Equator, which is the one that concerns us in this note, was led by Louis Godin (1704-1760), while Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (1698-1759) headed the expedition to Lapland. The knowledge of the shape and size of the Earth had great importance for the improvement of cartographic, geographic, and navigation techniques during that time. -

Final-Signatory List-Democracy Letter-23-06-2020.Xlsx

Signatories by Surname Name Affiliation Country Davood Moradian General Director, Afghan Institute for Strategic Studies Afghanistan Rexhep Meidani Former President of Albania Albania Juela Hamati President, European Democracy Youth Network Albania Nassera Dutour President, Federation Against Enforced Disappearances (FEMED) Algeria Fatiha Serour United Nations Deputy Special Representative for Somalia; Co-founder, Justice Impact Algeria Rafael Marques de MoraisFounder, Maka Angola Angola Laura Alonso Former Member of Chamber of Deputies; Former Executive Director, Poder Argentina Susana Malcorra Former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Argentina; Former Chef de Cabinet to the Argentina Patricia Bullrich Former Minister of Security of Argentina Argentina Mauricio Macri Former President of Argentina Argentina Beatriz Sarlo Journalist Argentina Gerardo Bongiovanni President, Fundacion Libertad Argentina Liliana De Riz Professor, Centro para la Apertura y el Desarrollo Argentina Flavia Freidenberg Professor, the Institute of Legal Research of the National Autonomous University of Argentina Santiago Cantón Secretary of Human Rights for the Province of Buenos Aires Argentina Haykuhi Harutyunyan Chairperson, Corruption Prevention Commission Armenia Gulnara Shahinian Founder and Chair, Democracy Today Armenia Tom Gerald Daly Director, Democratic Decay & Renewal (DEM-DEC) Australia Michael Danby Former Member of Parliament; Chair, the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee Australia Gareth Evans Former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Australia and -

Kimberly Martinez – ATA Member

Kimberly Martinez – ATA Member English and Spanish Translator Specializations: Legal and Special Education [email protected] +1 (626) 956-7817 Los Angeles, California – United States https://brighttranslation.com/ 1. Summary of Qualifications I am a fully qualified Freelance Translator with 6+ years of experience working for major translation agencies/companies. Extensive background in providing high quality translations in areas such as Legal, Financial, and Special Education. M.S. in Biological Sciences with numerous Diplomas in Language Arts. I am a knowledgeable translator with a strong command over English and Spanish having experience with multinational clients. 2. Language Pairs - English into Spanish - Spanish into English 3. Professional Skills Excellent written skills, advanced language knowledge and ability, attention to details, sound translation and review process, ability to organize and multi-task, calm professional with a flexible and adaptable approach to work, proficient in MS Word, Excel, Trados, Wordfast Anywhere, Memsource among others. 4. Areas of Expertise: Legal and Special Education. 5. Education Master of Biological Sciences University Simon Bolivar – Venezuela 2011 – 2014 English Language Arts Valencia Community College – Orlando, Florida 2010 Bachelor of Sciences, Major in Biology University of Carabobo - Venezuela 2004 – 2009 Modern Languages I and II University of Carabobo - Venezuela 2001 – 2002 Grammar and Spelling Extension Courses “Campo Elias School” – Venezuela 1999 6. Translator Experience 2012-2014 *Scientific Translator for University Simon Bolivar, Caracas - Venezuela Translation of Educational and Academic documents into English and Spanish for publications in scientific journals. Editing: Ecological and Biological Texts for classes, conferences, associations to enable people to communicate. 2015-2017 *Legal Translator for Los Angeles Immigration Services - California Translation of Legal documents into English for immigration purposes. -

Quid Iuris 26

Esta revista forma parte del acervo de la Biblioteca Jurídica Virtual del Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas de la UNAM www.juridicas.unam.mx http://biblio.juridicas.unam.mx LA VICEPRESIDENCIA DE LA REPÚBLICA EN LA HISTORIA CONSTITUCIONAL DE COLOMBIA Hernán Alejandro Olano García* SUMARIO: I. Introducción; II. La vicepresidencia en el constitucionalismo del siglo XIX; III. El último tramo de la vicepresidencia; IV. La vicepresidencia en la Carta de 1991; V. Remuneración del Vicepresidente; VI. Funciones del Vicepresidente; VII. Comisiones nacionales presididas por el Vicepresidente de la República; VIII. Programas presidenciales coordinados por el Vicepresidente; IX. Seguridad para los Expresidentes y Exvicepresidentes de la República; X. Futuro de la vicepresidencia; XI. El Vicepresidente en el constitucionalismo comparado latinoamericano; XII. Fuentes de consulta. *Abogado, con estancia Post Doctoral en Derecho Constitucional como Becario de la Fundación Carolina en la Universidad de Navarra, España y estancia Post Doctoral en Historia como Becario de AUIP en la Universidad del País Vasco, España; Doctor Magna Cum Laude en Derecho Canónico; es Magíster en Relaciones Internacionales y Magíster en Derecho. Es el Director del Programa de Humanidades en la Facultad de Filosofía y Ciencias Humanas de la Universidad de La Sabana, donde es Profesor Asociado, Director (e.) del Departamento de Historia y Estudios Socio Culturales y Director del Grupo de Investigación en Derecho, Ética e Historia de las Instituciones «Diego de Torres y Moyachoque, Cacique de Turmequé». Miembro de Número de la Academia Colombiana de Jurisprudencia, Miembro Correspondiente de la Academia Chilena de Ciencias Sociales, Políticas y Morales y Miembro Honorario del Muy Ilustre y Bicentenario Colegio de Abogados de Lima, Perú. -

How Land Ownership Is Being Concentrated in Colombia

OXFAM RESEARCH REPORTS DIVIDE AND PURCHASE How land ownership is being concentrated in Colombia Colombian law sets limits on the purchase of land previously awarded by the state to beneficiaries of agrarian reform processes, in order to avoid concentration of ownership and to preserve the social function of this land. Yet between 2010 and 2012, Cargill – the largest agricultural commodity trader in the world – acquired 52,576 hectares of such land in Colombia’s Altillanura region through 36 shell companies created for that purpose. As a result, Cargill may have managed to evade the legal restriction through a method of fragmented purchases, exceeding the maximum size of land permitted by law for a single owner by more than 30 times. The resolution of this and other similar cases that contribute to rural unrest will test the policy coherence of the Colombian government, which has recently faced major national protests over agrarian problems, while having committed itself at peace talks to a more democratic distribution of land and to strengthening the small-farm economy. www.oxfam.org CONTENTS Executive summary ............................................................................. 3 1 Introduction ....................................................................................... 5 2 Context ............................................................................................. 7 The issue of land in Colombia ..................................................................................... 7 Legal limits to land acquisition