Central Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geräumiges Einfamilienhaus Inherzen Walburgs

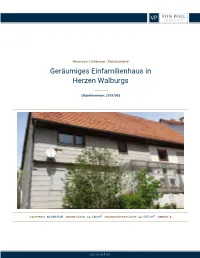

Hessisch Lichtenau - Deutschland Geräumiges Einfamilienhaus in Herzen Walburgs Objektnummer: 21037002 KAUFPREIS: 60.000 EUR WOHNFLÄCHE: ca. 140 m2 GRUNDSTÜCKSFLÄCHE: ca. 1577 m2 ZIMMER: 8 Objektnummer: 21037002 - 37235 Hessisch Lichtenau Auf einen Blick Die Immobilie Ein erster Eindruck Alles zum Standort Ansprechpartner Objektnummer: 21037002 - 37235 Hessisch Lichtenau Auf einen Blick Objektnummer 21037002 Kaufpreis 60.000 EUR Wohnfläche ca. 140 m² Provision Käuferprovision Grundstücksfläche ca. 1.577 m² beträgt 3,57 % (inkl. MwSt.) des Haustyp Einfamilienhaus beurkundeten Bezugsfrei ab 01.09.2021 Kaufpreises Bauweise Massiv Zimmer 8 Ausstattung Terrasse, Garten/ - Schlafzimmer 6 mitbenutzung, Badezimmer 2 Garten/‑mitbenutzung Dachform Satteldach Objektnummer: 21037002 - 37235 Hessisch Lichtenau Auf einen Blick: Energiedaten Energieinformation Zum Zeitpunkt der Anzeigenerstellung lag kein Energieausweis vor. Objektnummer: 21037002 - 37235 Hessisch Lichtenau Die Immobilie Ansicht Seitenansicht Objektnummer: 21037002 - 37235 Hessisch Lichtenau Die Immobilie Seitenansicht Kinderzimmer-Fenster- Objektnummer: 21037002 - 37235 Hessisch Lichtenau Die Immobilie Küche Treppenaufgang Objektnummer: 21037002 - 37235 Hessisch Lichtenau Die Immobilie Zimmer Flur-oben- Objektnummer: 21037002 - 37235 Hessisch Lichtenau Die Immobilie Badewanne/Dusche Kinderzimmer Objektnummer: 21037002 - 37235 Hessisch Lichtenau Die Immobilie Zimmer Wohnzimmer Objektnummer: 21037002 - 37235 Hessisch Lichtenau Die Immobilie Gestaltungsmöglichkeit-Garten- Objektnummer: -

Fahrplanheft Muenster 2019

Fahrplan Münster (Hessen) Gültig ab 9. Dezember 2018 2019 Ein kostenloser Service der RMV-Servicetelefon RMV-Mobilitätszentralen www.rmv.de 069 / 24 24 80 24 Kundenservice Benutzerhinweise DADINA, Europaplatz 1, 64293 Darmstadt Verkehrsbeschränkungen Ferien in Hessen (0 61 51) 3 60 51-0 S = nur an Schultagen 24.12.2018 - 12.1.2019 Mo.–Fr. 8–12.30 Uhr und Mo.–Do. 13–15.30 Uhr F = nicht an Schultagen 15.4.2019 - 27.4.2019 (0 61 51) 3 60 51-22 1.7.2019 - 9.8.2019 @ [email protected] www.dadina.de 30.9.2019 - 12.10.2019 RMV-Mobilitätszentrale Darmstadt | HEAG mobilo Kundenzentrum Zug, Bus oder Straßenbahn? Am Hauptbahnhof 20 a, Darmstadt | Luisenplatz 6, Darmstadt a Zugfahrten b S-Bahn-Fahrten (0 61 51) 3 60 51-51 | (0 61 51) 7 09-41 15 d Busfahrten e Straßenbahnfahrten Öffnungszeiten: Mo.–Fr. 8–18 Uhr und Sa. 9–16 | 13 Uhr An Silvester (31.12.), an Fastnacht (1.3. - 5.3.2019), am Schloss- Fahrplanauskünfte grabenfest (30.5. - 2.6.2019) und am Heinerfest (4.7. - 8.7.2019) wird RMV-Servicetelefon (täglich 24 Stunden) (0 69) 24 24 80 24 auf verschiedenen Linien Sonderverkehr gefahren. Entsprechende RMV-Mobilitätszentrale (0 61 51) 3 60 51-51 Fahrpläne werden zeitnah unter www.dadina.de eingestellt. NightLiner DADINA (0 61 51) 3 60 51-0 verkehren auch am 25.12.2018, am 3.3., 4.3., 5.3., 18.4., 19.4., 21.4., HEAG mobilo (0 61 51) 7 09-40 00 30.4., 29.5., 9.6., 19.6. -

Freiwilligentag 2018 Im Werra-Meißner-Kreis

Dokumentation Freiwilligentag 2018 im Werra-Meißner-Kreis Inhalt Grußwort des Landrates 5 Freiwilligentag in der Stadt Bad Sooden-Allendorf 7 Freiwilligentag in der Gemeinde Berkatal 16 Freiwilligentag in der Stadt Eschwege 18 Freiwilligentag in der Stadt Großalmerode 24 Freiwilligentag in der Gemeinde Herleshausen 29 Freiwilligentag in der Stadt Hessisch Lichtenau 37 Freiwilligentag in der Gemeinde Meinhard 46 Freiwilligentag in der Gemeinde Meißner 51 Freiwilligentag in der Gemeinde Neu Eichenberg 55 Freiwilligentag in der Gemeinde Ringgau 57 Freiwilligentag in der Stadt Sontra 63 Freiwilligentag in der Stadt Waldkappel 79 Freiwilligentag in der Stadt Wanfried 91 Freiwilligentag in der Gemeinde Wehretal 94 Freiwilligentag in der Gemeinde Weißenborn 99 Freiwilligentag in der Stadt Witzenhausen 101 weitere Teilnehmer 108 Presseartikel 109 3 Freiwilligentag 2018 im Werra-Meißner-Kreis Auftaktveranstaltung am 30.08.2018 in Sontra-Wichmannshausen Mit einem neuen Rekord findet der Kreisfreiwilligentag in diesem Jahr im Werra-Meißner- Kreis statt. 116 Aktionen haben sich für den 15. und 22. September gemeldet. 4 Freiwilligentag 2018 im Werra-Meißner-Kreis EIN KREIS EIN TAG – gemeinsam für uns Zum 11. Mal fand am 15. und 22. September der alljährliche kreisweite Freiwilligentag statt. Mit 110 angemeldeten Mitmach-Aktionen waren Engagierte in allen Kommunen an beiden Tagen am gemeinsamen Gestalten. In vielen Aktivitäten der Orte ging es darum, Orte der Begegnung, wie Dorf mitten, Grill- und Spielplätze aber auch die Friedhöfe in Ordnung zu bringen. Hecken schneiden, Beete säubern, Schaukästen neu streichen, Repararturarbeiten an Sitzgelegenheiten durchführen sind nur ei nige Beispiele für Aktivitäten, an denen sich viele Freiwillige beteiligen konnten. In manchen Orten wur den sogar zwei Mitmach-Aktionen angeboten. -

Bad Sooden-Allendorf Großalmerode Eschwege Herleshausen Sontra Waldkappel Hessisch Lichtenau Wanfried Witzenhausen

Wandern Fahrradverleih Ausfl ugsbus Schwimmbad A38 Marzhausen A7 Hermannrode Kanufahren Kino Berlepsch-Ellerode Hebenshausen M Neuenrode Hübenthal Berge Reiten Jugendherberge Blickershausen Gertenbach Albshausen Neu-Eichenberg Eichenberg/Bahnhof Eichenberg/Dorf M Badestrand Bowling Erlebnispark Ziegenhagen B80 B27 Ziegenhagen Ermschwerd Gute Angelmöglichkeit Minigolf Gewächshaus tropischer Nutzpfl anzen M Neuseesen Hubenrode Witzenhausen Stadtführung Bücherei Kirschwanderweg Unterrieden Werleshausen Premium-Wanderweg Kleinalmerode Ellingerode 9 Wendershausen 9 Roßbach Burg Ludwigstein M Museum Dohrenbach Oberrieden M Spiel- und Ellershausen Sportplätze fi nden sich Hundelshausen Ahrenberg in jedem Ort im Werra- Meißner-Kreis Bilsteinturm Gradierwerk mit Werrataltherme Hilgershausen Großalmerode Trubenhausen BadSooden-Allendorf M Kammerbach Salzmuseum B 451 Weißenbach Weiden Dudenrode Orferode 4 8 7 Kleinvach Uengsterode Hitzerode Epterode M Kripp- und Hielöcher B27 Hitzelrode Frankenhain Frankershausen Motzenrode Rommerode Berkatal Albungen Meinhard Laudenbach Wolfterode 2 Grube Gustav Neuerode Friedrichsbrück Frau Holle Teich Wellingerode Ve lmeden Meißner Jestädt Frau Holle Park Abteröder Bär M Fürstenhagen M Grebendorf Hausen Barfußpfad Vockerode Abterode Hessisch 1 Weidenhausen Schloss Wolfsbrunnen 5 Schwebda Germerode Niederhone M Frieda Quentel Lichtenau Walburg Nikolaiturm Plesseturm M B 249 EltmannshausenEschwege Bergwildpark Wanfrieder Hafen Alberode Oberhone Wanfried Hollstein Küchen Aue Elfengrund B 452M Kletterpark Rodebach Niddawitzhausen -

(190902 Sortierung Landkreise Übersicht Starke

Starke Heimat Hessen - Landkreise 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 (Summe von 2-7) Belastung - Abschöpfung Verbesserung gegenüber Rechnerischer Heimatumlage (75 %) Zuwachs bei den 2019 (Vollabschöpfung der Zuwachs der Erhöhungsbetrag für Fördermittel GKZ Kommunen zugunsten der kommunalen Schlüsselzuweisungen im KFA Digitalisierung der Kommunen Krankenhäuser** erhöhten Gewerbesteuereinnahmen Kindertageseinrichtungen Verwaltungskräfte Schule Familie (Hochrechnung * Gewerbesteuerumlage (120,7 Mio. Euro) gesamt 400 Mio. Euro) zugunsten des Landes) kreisfreie Städte 06411000 DARMSTADT, WISSENSCHAFTSSTADT 8.133.471 2.711.157 2.700.661 3.593.170 168.157 255.906 1.778.992 11.208.044 06412000 FRANKFURT AM MAIN, STADT 97.701.288 32.567.096 869.101 22.911.450 602.671 413.119 4.048.110 61.411.547 06413000 OFFENBACH AM MAIN, STADT 5.080.531 1.693.510 4.405.825 2.667.185 117.876 263.966 1.387.056 10.535.418 06414000 WIESBADEN, LANDESHAUPTSTADT 16.408.810 5.469.603 4.430.367 7.500.421 250.825 444.510 2.327.691 20.423.417 06611000 KASSEL, DOCUMENTA-STADT 9.157.158 3.052.386 5.148.458 3.872.262 197.630 381.823 2.897.614 15.550.172 Summe 136.481.258 45.493.753 17.554.411 40.544.488 1.337.158 1.759.324 12.439.464 119.128.598 Landkreis Bergstraße 06431000 LANDKREIS BERGSTRASSE - - 1.935.474 - 188.212 209.372 - 2.333.057 06431001 ABTSTEINACH 80.681 26.894 7.889 36.326 - 7.500 - 78.609 06431002 BENSHEIM, STADT 2.809.122 936.374 - 720.981 - 46.591 141.407 1.845.354 06431003 BIBLIS 101.731 33.910 55.009 130.240 - 16.298 - 235.457 06431004 BIRKENAU 141.688 47.229 102.655 154.496 -

Shoah: Intervention. Methods. Documentation. S:I.M.O.N

01/2016 S: I. M. O. N. SHOAH: INTERVENTION. METHODS. DOCUMENTATION. S:I.M.O.N. – Shoah: Intervention. Methods. DocumentatiON. ISSN 2408-9192 Issue 2016/1 Board of Editors of VWI’s International Academic Advisory Board: Gustavo Corni/Dieter Pohl/Irina Sherbakova Editors: Éva Kovács/Béla Rásky/Philipp Rohrbach Web-Editor: Sandro Fasching Webmaster: Bálint Kovács Layout of PDF: Hans Ljung S:I.M.O.N. is the semi-annual e-journal of the Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies (VWI) in English and German. Funded by: © 2016 by the Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies (VWI), S:I.M.O.N., the authors, and translators, all rights reserved. This work may be copied and redistributed for non-commercial, educational purposes, if permission is granted by the author(s) and usage right holders. For permission please contact [email protected] S: I. M. O. N. SHOAH: I NTERVENTION. M ETHODS. DOCUMENTATION. TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLES Suzanne Swartz Remembering Interactions 5 Interpreting Survivors’ Accounts of Interactions in Nazi-Occupied Poland Ionut Florin Biliuta Sowing the Seeds of Hate 20 The Antisemitism of the Orthodox Church in the Interwar Period Joanna Tokarska-Bakir The Hunger Letters 35 Between the Lack and Excess of Memory Johannes-Dieter Steinert Die Heeresgruppe Mitte 54 Ihre Rolle bei der Deportation weißrussischer Kinder nach Deutschland im Frühjahr 1944 Tim Corbett “Was ich den Juden war, wird eine kommende Zeit besser beurteilen …” 64 Myth and Memory at Theodor Herzl’s Original Gravesite in Vienna Sari J. Siegel The Past and Promise of Jewish Prisoner-Physicians’ Accounts 89 A Case Study of Auschwitz-Birkenau’s Multiple Functions David Lebovitch Dahl Antisemitism and Catholicism in the Interwar Period 104 The Jesuits in Austria, 1918–1938 SWL-READERS Susanne C. -

Datenhandbuch Deutscher Bundestag 1994 Bis 2003

Michael F. Feldkamp unter Mitarbeit von Birgit Strçbel Datenhandbuch zur Geschichte des Deutschen Bundestages 1994 bis 2003 Begrndet von Peter Schindler Eine Verçffentlichung der Wissenschaftlichen Dienste des Deutschen Bundestages Herausgeber: Verwaltung des Deutschen Bundestages Abteilung Wissenschaftliche Dienste/Referat Geschichte, Zeitgeschichte und Politik (WD 1) Verlag: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden Technische Umsetzung: bsix information exchange GmbH, Braunschweig ISBN 3-8329-1395-5 (Printausgabe) Deutscher Bundestag, Berlin 2005 Vorwort Die parlamentarische Demokratie ist auf das wache Interesse ihrer Brgerinnen und Brger angewiesen. Aber wer auch immer sich mit der wichtigsten Institution unse- res parlamentarischen Regierungssystems, dem Deutschen Bundestag, beschftigen mçchte, ob es um die Beteiligung an einer Diskussion geht, um Kritik, Ablehnung oder Zustimmung, fr den ist eine Grundkenntnis wichtiger Daten, Fakten, Zusam- menhnge und Hintergrnde unverzichtbar. Vor rund 25 Jahren, aus Anlass des 30jhrigen Bestehens des Deutschen Bundesta- ges, haben die Wissenschaftlichen Dienste deshalb erstmals versucht, die Daten und Fakten zu Leistung, Struktur und Geschichte des Deutschen Bundestages in einer Dokumentation zusammenzustellen, nach denen mit Recht hufig gefragt wird und die bis dahin jeweils einzeln von den verschiedenen Organisationseinheiten der Ver- waltung erfragt oder unterschiedlichen Publikationen entnommen werden mussten. ber die Jahre hinweg hat sich aus dieser Dokumentation das Datenhandbuch und damit -

Eppertshausen

Partner Abfallkalender www.da-di-werk.de www.zaw-online.de ZAW Abfall-App Eppertshausen www.azurgmbh.de 2021Biotonne JANUAR FEBRUAR MÄRZ APRIL MAI JUNI 5 9 1 Fr Neujahr 1 Mo 1 Mo 1 Do 1 Sa Maifeiertag 1 Di Altpapiertonne & -container 2 Sa 2 Di 2 Di 2 Fr Karfreitag 2 So 2 Mi 18 3 So 3 Mi 3 Mi 3 Sa 3 Mo 3 Do Fronleichnam 1 Restmülltonne & -container 4 Mo 4 Do 4 Do 4 So Ostersonntag 4 Di 4 Fr 14 5 Di 5 Fr 5 Fr 5 Mo Ostermontag 5 Mi 5 Sa Restmüllcontainer – 6 Mi 6 Sa 6 Sa 6 Di 6 Do 6 So nur wöchentliche Leerung 23 7 Do 7 So 7 So 7 Mi 7 Fr 7 Mo 6 10 Gelbe Säcke 8 Fr 8 Mo 8 Mo 8 Do 8 Sa 8 Di 9 Sa 9 Di 9 Di 9 Fr 9 So 9 Mi 10 So 10 Mi 10 Mi 10 Sa 10 Mo 10 Do 2 19 11 Mo 11 Do 11 Do 11 So 11 Di 11 Fr Reklamationen zur Abfuhr 15 Bio Papier Restmüll Sperrmüll 12 Di 12 Fr 12 Fr 12 Mo 12 Mi 12 Sa Reso GmbH 13 Mi 13 Sa 13 Sa 13 Di 13 Do Christi Himmelfahrt 13 So Hotline: 06159 7175930 24 E-Mail: [email protected] 14 Do 14 So 14 So 14 Mi 14 Fr 14 Mo Nur Gelber Sack-Reklamationen 7 11 15 Fr 15 Mo 15 Mo 15 Do 15 Sa 15 Di REMONDIS GmbH & Co. -

Classified Advertising 643-2711

n - MANCHESTER HERALD. Monday, June 9, 19M CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING 643-2711 MANCHESTER SPORTS Despite caution, M HS prom has Wynegar’s hit HOMES I APARTMENTS MISCELLANEOUS FOR SALE FOR RENT FURNITURE FOR SALE abuse is possibie lots of Scarlett lifts the Yanks Manchester. Spacious liv 3 Room Apartment-First MovIn^^MusfSeM^ai^ BUSINESS & SERVICE DIREaORY ing. 2 both Cape. Fire- floor, large rooms, stove, ganv dining room set $500. ... p a g e 3 p a g e 1 1 ... page 15 placed living room with refrigerator, heat and hot King size bed with 3 sets of cathedral celling. Large water, garage, laundry sheets $125. Twin bed ENDROLLS facilities, very clean. $475. frame with matching 6 27<A width - 2Sa 1 ^ CARPENTRY/ MISCELLANEOUS lot! $135,900 "W e guaran 13V« width - 2 tor 28* HEATIN8/ tee our houses" Blan Lease and security. Ask drawer dresser $100. CHILDCARE 1001 |TREMODEUNB---- PLUMBIN8 SERVICES chard & Rosetto Real about Senior Citizen dis Other miscellaneous 646- MUST be picked up at the Estate 646-2482. counts. Call 646-7268. 6332 evenings. Manchester Herald Office before 11 A M. ONLY. Carpentry and remodel- Fogarty Brothers — Ba 4 Room Apartment. No Ing services — Complete throom remodelino; In Coventrv-Horse Lover- King Size water bed, stallation water heater.<, s..Huge 5 bedroom home Pets, country living, good heater, padded side rails, home repairs and remo for working couple. Se will do bobytlfflng In mv deling. Quality work. Ref garbage disposals; faucet D 8i D Landscaping. on 6.8 acres, 750 foot head board. Excellent CARS Licensed Manchester repairs. -

The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist a Dissertation Submitted In

The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jonah D. Levy, Chair Professor Jason Wittenberg Professor Jacob Citrin Professor Katerina Linos Spring 2015 The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe Copyright 2015 by Kimberly Ann Twist Abstract The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Jonah D. Levy, Chair As long as far-right parties { known chiefly for their vehement opposition to immigration { have competed in contemporary Western Europe, scholars and observers have been concerned about these parties' implications for liberal democracy. Many originally believed that far- right parties would fade away due to a lack of voter support and their isolation by mainstream parties. Since 1994, however, far-right parties have been included in 17 governing coalitions across Western Europe. What explains the switch from exclusion to inclusion in Europe, and what drives mainstream-right parties' decisions to include or exclude the far right from coalitions today? My argument is centered on the cost of far-right exclusion, in terms of both office and policy goals for the mainstream right. I argue, first, that the major mainstream parties of Western Europe initially maintained the exclusion of the far right because it was relatively costless: They could govern and achieve policy goals without the far right. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SHAREOK repository UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE LIFE AND WORK OF GRETEL KARPLUS/ADORNO: HER CONTRIBUTIONS TO FRANKFURT SCHOOL THEORY A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of P hilosophy BY STACI LYNN VON BOECKMANN Norman, Oklahoma 2004 UMI Number: 3147180 UMI Microform 3147180 Copyright 2005 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 THE LIFE AND WORK OF GRETEL KARPLUS/ADORNO: HER CONTRIBUTIONS TO FRANKFURT SCHOOL THEORY A Dissertation APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH BY ____________________________ _ Prof. Catherine Hobbs (Chair) _____________________________ Prof. David Gross ____________________________ _ Assoc. Prof. Susan Kates _____________________________ Prof. Helga Madland _____________________________ Assoc. Prof. Henry McDonald © Copyright by Staci Lynn von Boeckmann 2004 All Rights Reserved To the memory of my grandmother, Norma Lee Von Boeckman iv Acknowledgements There a number of people and institutions whose contributions to my work I would like to acknowledge. For the encouragement that came from being made a Fulbright Alternative in 1996, I would like to thank t he Fulbright selection committee at the University of Oklahoma. I would like to thank the American Association of University Women for a grant in 1997 -98, which allowed me to extend my research stay in Frankfurt am Main. -

Rainer Werner Fassbinder's Garbage, the City and Death: Renewed

Rainer Werner Fassbinder's Garbage, the City and Death: Renewed Antagonisms in the Complex Relationship between Jews and Germans in the Federal Republic of Germany Author(s): Andrei S. Markovits, Seyla Benhabib, Moishe Postone Reviewed work(s): Source: New German Critique, No. 38, Special Issue on the German-Jewish Controversy (Spring - Summer, 1986), pp. 3-27 Published by: New German Critique Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/488073 . Accessed: 30/11/2011 17:42 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. New German Critique and Duke University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to New German Critique. http://www.jstor.org Rainer WernerFassbinder's Garbage, the City and Death: RenewedAntagonisms in the ComplexRelationship Between Jews and Germansin TheFederal Republic of Germany* OnDecember 17, 1985 about40people gathered at theCen- terforEuropean Studies to hearpresentations on various aspects of thecontroversy surrounding the Fassbinderplay, Garbage, the City and Death, (DerMidll, die Stadtund der Tod).The eventwas sponsoredby two of the Center'sstudy groups: The Jews in ModemEurope Study Group and TheGerman Study Group. Theimmediate contextfor this seminar was set bythe Bitburg incidentand its aftermathin thelate springof 1985.