The Collaboration and Art of the Siti Company Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blocking Fathers, Illicit Marriages: Continuity and Change from Sophocles to Menander

Blocking Fathers, Illicit Marriages: Continuity and Change from Sophocles to Menander It is a truth universally acknowledged that the plays of Menander owe a great debt to Classical Athenian drama: connections between plays such as Aristophanes’ Cocalus and Menander were noted in didascalia, and similarly the thematic and structural similarities between New Comedy and the works of Euripides were already recognized in Hellenistic scholarship (Arnott 1972; Csapo 2000; Hunter 2011). Sophocles, on the other hand, is rarely included in this discussion of dramatic influence, more often regarded solely for his role as the pinnacle of tragic poets. It is the purpose of this paper to reanalyze possible connections between the corpus of Sophocles and that of Menander by examining both the Antigone and the Dyscolus as plays employing one of the most familiar stock characters of ancient comedy: the “blocking” father figure. This father figure—whose earliest incarnation arguably belongs to Old Comedy, such as Strepsiades from Clouds—is perhaps best known for his characterization in the plays of Greek New Comedy and their later, Latin iterations. Generally an old and intransigent father, the “blocking” figure is generically defined by his interference in the life of his young offspring; in New Comedy, this interference takes the form of intervention in the budding romance of two young lovers, whose inconvenient marriage will inevitably bring about the typical finale. This character, at first glance, may appear to be a creature created solely for light-hearted drama. Creon of the Antigone, however, whose stubborn and belligerent character has been carefully surveyed for his role within the tragedy itself (see Roisman 1996), additionally shares many features with the father of Menander’s only intact play, Knemon of the Dyscolus. -

Stagehand Course Curriculum

Alaska Center for the Performing Arts Stagehand Training Effective July 1, 2010 1 Table of Contents Grip 3 Lead Audio 4 Audio 6 Audio Boards Operator 7 Lead Carpenter 9 Carpenter 11 Lead Fly person 13 Fly person 15 Lead Rigger 16 Rigger 18 Lead Electrician 19 Electrician 21 Follow Spot operator 23 Light Console Programmer and Operator 24 Lead Prop Person 26 Prop Person 28 Lead Wardrobe 30 Wardrobe 32 Dresser 34 Wig and Makeup Person 36 Alaska Center for the Performing Arts 2 Alaska Center for the Performing Arts Stagecraft Class (Grip) Outline A: Theatrical Terminology 1) Stage Directions 2) Common theatrical descriptions 3) Common theatrical terms B: Safety Course 1) Definition of Safety 2) MSDS sheets description and review 3) Proper lifting techniques C: Instruction of the standard operational methods and chain of responsibility 1) Review the standard operational methods 2) Review chain of responsibility 3) Review the chain of command 4) ACPA storage of equipment D: Basic safe operations of hand and power tools E: Ladder usage 1) How to set up a ladder 2) Ladder safety Stagecraft Class Exam (Grip) Written exam 1) Stage directions 2) Common theatrical terminology 3) Chain of responsibility 4) Chain of command Practical exam 1) Demonstration of proper lifting techniques 2) Demonstration of basic safe operations of hand and power tools 3) Demonstration of proper ladder usage 3 Alaska Center for the Performing Arts Lead Audio Technician Class Outline A: ACPA patching system Atwood, Discovery, and Sydney 1) Knowledge of patch system 2) Training on patch bays and input signal routing schemes for each theater 3) Patch system options and risk 4) Signal to Voth 5) Do’s and Don’ts B: ACPA audio equipment knowledge and mastery 1) Audio system power activation 2) Installation and operation of a mixing consoles 3) Operation of the FOH PA system 4) Operation of the backstage audio monitors 5) Operation of Center auxiliary audio systems a. -

University of California Santa Cruz Dissecting

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ DISSECTING DRAMATURGICAL BODIES: Self, Sensibility, and Gaze in Contemporary Dramaturgy A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THEATER ARTS by Patrick Denney This thesis of Patrick Denney is Approved by: _____________________________________ Professor Michael Chemers, PHD, Chair _____________________________________ Professor Gerald Casel, MFA _____________________________________ Professor Philippa Kelly, PHD _____________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….iv Dedication………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………v “Killing” Theater: A Survey of Popular Depictions of Dramaturgy……………………………………………………………1 Brecht’s Electrons: Positioning the Dramaturg in The Messingkauf Dialogues and Beyond…………………….5 Doctor to Dramaturg, and Back Again: Defining the Dramaturgical Gaze………………………………………………10 Pharmaturg to Dramaturg: Pharmakos and Dionysian Dramaturgy………………………………………………………18 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….33 iii ABSTRACT: DISSECTING DRAMATURGICAL BODIES: Self, Sensibility, and Gaze in Contemporary Dramaturgy By Patrick Denney Dramaturgy is an art form that is still, after decades of existence in the American theater, misunderstood, and often feared, by many theater artists. From quasi-realistic portrayals of TV Shows such as SMASH, to the pulpy B-movie depiction of Law and Order: Criminal -

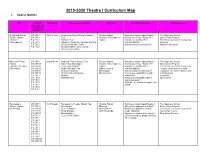

2019-2020 Theatre I Curriculum Map I

2019-2020 Theatre I Curriculum Map I. Course Outline Unit Current Timeframe Assessments/Activities Big Idea Essential Questions Core Resources Arkansas SS Framework Alignment Greek and Roman CR.1.TH.1 1st 9 Weeks Greeks and Roman Theatre History Theatre History How does history impact theatre? The Stage and School Theatre History P.4.THI.2 Test Character Development How do you create characters? Basic Drama Projects Character P.4.THI.3 Antigone Test Improv How does empathy affect The Drama Classroom Companion Development P.4.THI.5 Napoleon Dynamite Character Analysis characterization? Antigone P.5.THI.2 Life Size Character Poster How do characters affect plot? Napoleon Dynamite P.6.THI.2 Character Observation Journal Greek Theatre Mask Medieval Theatre CR.1.TH.1 2nd 9 Weeks Medieval Theatre History Test Theatre History How does history impact theatre? The Stage and School History CR.2.THI.1 Solo Acting Monologue Character Development How do you create characters? Basic Drama Projects Character Creation CR.2.THI.2 Theme Assessment Improv How does empathy affect The Drama Classroom Companion Solo Acting CR.1.THI.3 Modern Morality Play Acting Theories characterization? Veggies Tales used as modern CR.1.THI.4 Character Analysis Monologues How do characters affect plot? (examples of mystery, miracle, and CR.3.THI.1 Character Design Morgue Memorization How do you establish believable morality plays) P.5.THI.1 Audition characters? Everyman P.5.THI.2 Self Reflection How does memorization affect Monologues P.5.THI.4 characterization? P.5.THI.5 -

World Theatre Day 2021 Event Report

International Theatre Institute ITI World Organization for the Performing Arts World Theatre Day 2021 Event Report 27 March 2021 Online Celebration Under the patronage of UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization www.world-theatre-day.org Content Introduction 3 Welcome Address by Tobias BIANCONE, Director General of ITI 4 Welcome Address by Ernesto Renato OTTONE RAMIREZ, 5 UNESCO Assistant Director-General for Culture World Theatre Day 2021 Message Author 6 World Theatre Day 2021 Message 7 Interview | Helen MIRREN Thoughts on Theatre for World Theatre Day 2021 8 An Invitation to Watch the Event and its Performances 10 Main Online Celebration Programme 11 Main Celebration 14 Performance Videos from ITI Centres 15 Performance Videos from World Performing Arts Communities 23 Special Projects 26 Inspirational Moments 27 Presentations 28 Promotion 29 Worldwide Events of World Theatre Day 34 Promotion in China 36 Event Participation 37 The Outcome 38 Event Organizers 39 Expression of Gratitude 40 Participation List 41 Click this icon, back to Content page. Introduction Due to the unpromising situation of the global pandemic, The WTD 2021 online Celebration was held under the the General Secretariat of ITI was unable to organize the main Shakespearean theme “All the world’s a stage”. Facing the Celebration of World Theatre Day 2021 at UNESCO in Paris as lockdown and isolation caused by the pandemic, the planned. performing arts communities have been forced, much like the WTD Celebration, to create their platforms virtually – but However, since the world is getting more used to attending where there is theatre, there is a stage. -

NAYATT SCHOOL REDUX (Since I Can Remember)

THE WOOSTER GROUP NAYATT SCHOOL REDUX (Since I Can Remember) DIRECTOR’S NOTE Our work on this piece began when filmmaker Ken Kobland and I set out to make an archival video reconstruction of The Wooster Group’s 1978 piece Nayatt School. Nayatt School featured Spalding Gray’s first experiments with the monologue form and included scenes from T.S. Eliot’s play The Cocktail Party. Nayatt School was the third part of a trilogy of pieces that I directed that were made around Spalding’s autobiography: his family history, his life in the theater, and his mother’s suicide. As Ken and I worked with the Nayatt School materials, we found that the surviving video and audio recordings were too fragmentary, and their original quality too poor, to make a full reconstruction. So I decided to remount Nayatt School with our present company – especially while a few of us, who were there, could still remember. We could at least fill in the gaps for an archival record and, at the same time, demonstrate our process for devising our work. Of course, in reanimating Nayatt School, we have discovered that when it is placed in a new time and context, new possibilities and resonances emerge. I recognize that we are not just making an archival record — we are in the process of making a new piece. That is the work in progress that you are about to see. work-in-progress theatro-film THE PERFORMING GARAGE May 2019 NAYATT SCHOOL REDUX (Since I Can Remember) with Ari Fliakos, Gareth Hobbs, Erin Mullin, Suzzy Roche, Scott Shepherd, Kate Valk, Omar Zubair Composed by the -

Curriculum Vita

LENORA CHAMPAGNE 3 Horatio Street, New York, NY 10014 212.924.6577 [email protected]; [email protected] websites: www.lenorachampagne.com; www.purchase.edu EDUCATION Ph.D. in Performance Studies, New York University, 1980 Thesis: "From `Imagination to Power' to the `Hyper-Real': May 1968 and French Theatre" Published as French Theatre Experiment Since 1968, UMI Research Press, l984 M.A. Drama, New York University, l975 B.A. English, Louisiana State University, l972 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE—TEACHING Purchase College, State University of New York Professor and Coordinator of Theatre and Performance (presently) Kempner Distinguished Professor, 2008-2010 Royal and Shirley Durst Chair of Humanities, 2002-2004 Associate Professor, Drama Studies, Fall 2001 to Spring 2008 Assistant Professor, Drama Studies, Fall 1999 to Spring 2001 Member of Theatre and Performance, Dramatic Writing and Gender Studies Boards of Study New York University, Gallatin School for Individualized Study Adjunct Faculty, (Solo Performance Composition to graduate and undergraduate students) since 1980 Thesis and academic advisor for graduate students and for independent studies in performance art. Trinity College, Dept. of Theatre and Dance, Hartford, CT Artist-in-Residence, full-time faculty, l985 - 1989 Directed two productions annually, Main Stage and Black Box TEACHING: SOLO PERFORMANCE WORKSHOPS Trinity/LaMama, Fall 1995-2005 Sanctuary for Families, 1998-1999 (as Public Imaginations affiliated artist, Dance Theatre Workshop) Movement Research, Spring 1991-1993 -

To View Our Program

About Villanova University Since 1842, Villanova University’s Augustinian Catholic intellectual tradition has been the cornerstone of an academic community in which students learn to think critically, act compassionately and succeed while serving others. There are more than 10,000 undergraduate, graduate and law students in the Univer- sity’s six colleges – the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, the Villanova School of Business, the College of Engineering, the College of Nursing, the College of Professional Studies and the Villanova University School of Law. As students grow intellectually, Villanova prepares them to become ethical leaders who create positive change everywhere life takes them. In Gratitude The faculty, staff, and students of Villanova Theatre extend sincere gratitude to those generous benefactors who have established endowed funds in support of our efforts: Marianne M. and Charles P. Connolly, Jr. ’70 Dorothy Ann and Bernard A. Coyne, Ph.D. ̓55 Patricia M. ’78 and Joseph C. Franzetti ’78 Peter J. Lavezzoli ’60 Mary Anne C. Morgan ̓70 and Family & Friends of Brian G. Morgan ̓67, ̓70 Anthony T. Ponturo ’74 For information about how you can support the Theatre Department, please contact Heather Potts-Brown, Director of Annual Giving, at (610) 519-4583. Villanova Theatre gratefully acknowledges the generous support of its many patrons & subscribers We wish to offer special thanks to our 14-15 Benefactors: This list is updated as of November 1, 2014 A Running Friend Delia Mullaney Bill & Mimi Nolan John L. Abruzzo, M.D. Peggy & Bill Hill Beverly Nolan Donna Adams-Tomlinson Nancy & Joseph Hopko Dr. & Mrs. Bruce Northrup Loretta Adler Kerri L. -

Demarcating Dramaturgy

Demarcating Dramaturgy Mapping Theory onto Practice Jacqueline Louise Bolton Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Workshop Theatre, School of English August 2011 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his/her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 11 Acknowledgements This PhD research into Dramaturgy and Literary Management has been conducted under the aegis of an Arts and Humanities Research Council Collaborative Doctoral Award; a collaboration between the University of Leeds and West Yorkshire Playhouse which commenced in September 2005. I am extremely grateful to Alex Chisholm, Associate Director (Literary) at West Yorkshire Playhouse, and Professor Stephen Bottoms and Dr. Kara McKechnie at the University of Leeds for their intellectual and emotional support. Special thanks to Professor Bottoms for his continued commitment over the last eighteen months, for the time and care he has dedicated to reading and responding to my work. I would like to take this opportunity to thank everybody who agreed to be interviewed as part of this research. Thanks in particular to Dr. Peter Boenisch, Gudula Kienemund, Birgit Rasch and Anke Roeder for their insights into German theatre and for making me so welcome in Germany. Special thanks also to Dr. Gilli Bush-Bailey (a.k.a the delightful Miss. Fanny Kelly), Jack Bradley, Sarah Dickenson and Professor Dan Rebellato, for their faith and continued encouragement. -

Term-List-For-Ch4-Asian-Theatre-2

Asian Theatre: India, China, Korea, Japan, Indonesia, & Cambodia Cultural Periods and Events Theatrical Developments Persons Aryan migration & caste system Natya-Shastra (rasas & the Bharata Muni & Abhinavagupta Vedic & Gandhara Periods spectator’s liberation) Shūdraka & Kalidasa Hinduism & Sanskrit texts Islamic invasions actor-manager (sudtradhara) Buddhism (promising what?) shamanic rituals jester (vidushaka) Hellenistic influence court entertainments with string-puller (sudtradhara) Classical Period & Ashoka Jester Ming sheng, dan, jing, & chou (meanings) Theravada & Mahayana wrestling & Baixi men & women who played across gender Gupta golden age impersonations, dances, & women who led troupes Medieval Period acrobatics, sword tricks Guan Hanqing Muslim invasions small plays of song and dance Tang Xianzu Chola Dynasty Pear Garden & adjutant Li Yu Early Modern Period plays Kan’ami & Zeami Mughal Empire red light districts with shite & shite-tsure (across gender), waki, Colonial Period with British East southern dramas & waki-tsure, & kyogen India Company variety show musicals chorus of 8 men, musicians, & onstage British Raj with one star singing per stagehand (kuroko) Dramatic Performances Act act Okuni Contemporary Period complex, poetic dramas onnagata Shang, Zhou, Qin, Han, Jin, kun operas with plaintive Chikamatsu Northern & Southern, Sui, Tang, music & flowing Danjuro I Song, Yuan, Ming, & Qing melodies/dancing chanter, 3 puppeteers per puppet, & Dynasties Beijing Opera (jingju) as shamisen player nationalist & communist rulers -

The Kitchen Center for Video, Music and Dance

THE KITCHEN CENTER FOR VIDEO, MUSIC AND DANCE December 29, 1979 Woody,Steina Vasulka 257 Franklin Street Buffalo, New York 14202 Dear Woody and Steina, Enclosed is a rough draft of the videotape catalogue we're trying to put together . A few tapes are listed under your name . Could you please look over this information and make corrections, exclamations and changes where necessary . I would like to have your changes or OK by the end of February if possible . Thanks for the trouble . Board of Directors Robert Ashley Paula Cooper Suzanne Delehanty Philip Glass Barbara London Mary MacArthur Barbara Pine Carlota Schoolman Robert Stearns John Stewart Caroline Thorne Paul Walter HALEAKALA, INC. 59 WOOSTER NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10012 (212) 925-3615 ARTIST ADDRESS PHONE NAME OF TAPE CORRECTIONS/ADDITIONS SUGGESTIONS ARTIST (S) TITLEUS) TIME Ga n m r 0 0 0 cc w r a m wm AARON , Jane and When I Was A Worker Like LaVerne r 0 r n rt N~ x n a0 n BLUMBERG , Skip 29 minutes 0 w 0 K A straightforward account of both management and labor at a w rr Sears and Roebuck Company mail order house in Chicago . The m m plant foreman explains some of the operations of the business n with a tour through the nine floor structure, spotted along m with interviews with workers at a variety of duties, who appear to genuinely enjoy their labors . x R X X x Note : Copy #1 ACCONCI , Vito Red Tapes 140 minutes I, Common Knowledge Picture plane space - novelistic - scheme of detective story . -

Story the Viewp

Unpublished Notes on the Viewpoint of Story Based on the Work of Mary Overlie Wendell Beavers (Copyright 2000) Story The Viewpoint of Story has a particular provenance which is rooted in a moment of dance history which declared itself anti-story, anti literal and anti illusion.* Several of the most powerful storytelling experiences in the theater I ever witnessed were performances of the Grand Union, a group made up of participants of the Judson Dance Theater. Its members were perceived as both heroic and legendary performers and disgusting cheapeners of the magic that was supposed to happen in the theater. The divide was mostly generational and the result of a natural sort of overthrow of what came before. Their brand of open improvisational performance featured precipitous surprises and a kind of high drama difficult to explain because of the ordinary circumstances from which these events always managed somehow to arise. The next “thing” to happen always seemed inevitable after the fact, but completely impossible to anticipate the moment before. This was storytelling--which got labeled post-modern--but in retrospect had a peculiar link to shamanistic story telling. It may be jarring to link post modernism with shamanism because we associate shamanism with the cultivation and communication of spiritual or other worldly things. Postmodern performers of the sixties and seventies were looking into themselves and their immediate environment. They were communicating or pointing out the nature of the material world before us. There was not supposed to be anything otherworldly about it. The ordinary magic that they practiced and bequeathed to the next generation was quite subversive to the modern dance sensibility, not to mention the high art theater world of ballet etc.