A Proposal for an Integrated Rehearsal Methodology for Shakespeare (And Others) Combining Active Analysis and Viewpoints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SS Issue 4 New Master FINAL

Issue #4, May 2014 Contents / Содержание Sergei Tcherkasski (St Petersburg State Theatre Arts Academy, Russia): Inside Sulimov’s Studio: Directors Perform a Play - pg. 4/ Сергей Черкасский (Санкт-Петербургская государственная академия театрального искусства, Россия): «В мастерской М. В. Сулимова: Режиссеры играют спектакль» – с. 26 Peter Zazzali (University of Kansas, U.S.A): An Examination of the Actor’s Double-Consciousness Through Stanislavski’s Conceptualization of ‘Artistic Truth’ - pg. 47/ Питер Заззали (Канзасский университет, США): «Исследование двойственного сознания актера посредством концептуализированной Станиславским идеи ‘сценической правды’» - с. 56 Michael Craig (Copernicus Films, Moscow): Vakhtangov and the Russian Theatre: Making a new documentary film - pg. 66 / Майкл Крэг («Copernicus Films», Москва): «Вахтангов и русский театр. Создание нового документального фильма» – с. 72 Steven Bush (University of Toronto, Canada): George Luscombe and Stanislavski Training in Toronto - pg. 79/ Стивен Буш (Университет Торонто, Канада): «Джордж Ласком и преподавание по методу Станиславского в Торонто» – с. 93 David Chambers (Yale School of Drama): Études in America: A Director’s Memoir - pg. 109/ Дэвид Чемберс (Йельская школа драмы): «Этюды в Америке: Воспоминания режиссера» – с. 126 Eilon Morris (UK) : The Ins and Outs of Tempo-Rhythm - pg. 146 /Эйлон Моррис (Великобритания): «Особенности темпоритма» – с. 159 Martin Julien (University of Toronto) : “Just Be Your Self-Ethnographer”: Reflections on Actors as Anthropologists - pg. -

The Kitchen Center for Video, Music and Dance

THE KITCHEN CENTER FOR VIDEO, MUSIC AND DANCE December 29, 1979 Woody,Steina Vasulka 257 Franklin Street Buffalo, New York 14202 Dear Woody and Steina, Enclosed is a rough draft of the videotape catalogue we're trying to put together . A few tapes are listed under your name . Could you please look over this information and make corrections, exclamations and changes where necessary . I would like to have your changes or OK by the end of February if possible . Thanks for the trouble . Board of Directors Robert Ashley Paula Cooper Suzanne Delehanty Philip Glass Barbara London Mary MacArthur Barbara Pine Carlota Schoolman Robert Stearns John Stewart Caroline Thorne Paul Walter HALEAKALA, INC. 59 WOOSTER NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10012 (212) 925-3615 ARTIST ADDRESS PHONE NAME OF TAPE CORRECTIONS/ADDITIONS SUGGESTIONS ARTIST (S) TITLEUS) TIME Ga n m r 0 0 0 cc w r a m wm AARON , Jane and When I Was A Worker Like LaVerne r 0 r n rt N~ x n a0 n BLUMBERG , Skip 29 minutes 0 w 0 K A straightforward account of both management and labor at a w rr Sears and Roebuck Company mail order house in Chicago . The m m plant foreman explains some of the operations of the business n with a tour through the nine floor structure, spotted along m with interviews with workers at a variety of duties, who appear to genuinely enjoy their labors . x R X X x Note : Copy #1 ACCONCI , Vito Red Tapes 140 minutes I, Common Knowledge Picture plane space - novelistic - scheme of detective story . -

Story the Viewp

Unpublished Notes on the Viewpoint of Story Based on the Work of Mary Overlie Wendell Beavers (Copyright 2000) Story The Viewpoint of Story has a particular provenance which is rooted in a moment of dance history which declared itself anti-story, anti literal and anti illusion.* Several of the most powerful storytelling experiences in the theater I ever witnessed were performances of the Grand Union, a group made up of participants of the Judson Dance Theater. Its members were perceived as both heroic and legendary performers and disgusting cheapeners of the magic that was supposed to happen in the theater. The divide was mostly generational and the result of a natural sort of overthrow of what came before. Their brand of open improvisational performance featured precipitous surprises and a kind of high drama difficult to explain because of the ordinary circumstances from which these events always managed somehow to arise. The next “thing” to happen always seemed inevitable after the fact, but completely impossible to anticipate the moment before. This was storytelling--which got labeled post-modern--but in retrospect had a peculiar link to shamanistic story telling. It may be jarring to link post modernism with shamanism because we associate shamanism with the cultivation and communication of spiritual or other worldly things. Postmodern performers of the sixties and seventies were looking into themselves and their immediate environment. They were communicating or pointing out the nature of the material world before us. There was not supposed to be anything otherworldly about it. The ordinary magic that they practiced and bequeathed to the next generation was quite subversive to the modern dance sensibility, not to mention the high art theater world of ballet etc. -

Barbara Dilley & Yvonne Rainer with Wendy Perron

Danspace Project Conversations Without Walls: Barbara Dilley & Yvonne Rainer with Wendy Perron November 21, 2020 Judy Hussie-Taylor Welcome to Danspace Project and our Conversation Without Walls. I'm Judy Hussie-Taylor, Executive Director & Chief Curator. I'm honored to welcome three people I hold in high esteem, Barbara Dilley, Yvonne Rainer, and Wendy Perron. Thank you all for joining us today to celebrate Wendy's new book "The Grand Union: Accidental Anarchists of Downtown Dance 1970-76" published by Wesleyan University Press. So this is an exciting occasion. I just quickly want to thank our Danspace staff and our behind the scenes wizards, especially Yolanda Royster and Ben Kimitch, for holding us all together today on the Zoom. So all three of our guests have extensive histories with Danspace Project. Barbara Dilley co-founded Danspace Project, along with Mary Overlie and Larry Fagin in 1974. Prior to that, Barbara was a member of Merce Cunningham's company from 1963 to 1968. She danced with Yvonne Rainer from 1966 to 1970 and was a member of the Grand Union, which you'll hear a lot about today. She was instrumental in the founding of Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado, which is where I met Barbara. She designed the dance department and served as the University's President from 1985 to 1993. Most recently, she is the author of "This Perfect Moment, Teaching Thinking Dancing," which is part autobiography, part workbook. Choreographer, filmmaker, and the author of many books, Yvonne Rainer was a co-founding member of Judson Dance Theater in 1962. -

Lloyd Richards in Rehearsal

Lloyd Richards in Rehearsal by Everett C. Dixon A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Theatre Studies, York University, Toronto, Ontario September 2013 © Everett Dixon, September 2013 Abstract This dissertation analyzes the rehearsal process of Caribbean-Canadian-American director Lloyd Richards (1919-2006), drawing on fifty original interviews conducted with Richards' artistic colleagues from all periods of his directing career, as well as on archival materials such as video-recordings, print and recorded interviews, performance reviews and unpublished letters and workshop notes. In order to frame this analysis, the dissertation will use Russian directing concepts of character, event and action to show how African American theatre traditions can be reformulated as directing strategies, thus suggesting the existence of a particularly African American directing methodology. The main analytical tool of the dissertation will be Stanislavsky's concept of "super-super objective," translated here as "larger thematic action," understood as an aesthetic ideal formulated as a call to action. The ultimate goal of the dissertation will be to come to an approximate formulation of Richards' "larger thematic action." Some of the artists interviewed are: Michael Schultz, Douglas Turner Ward, Woodie King, Jr., Dwight Andrews, Stephen Henderson, Thomas Richards, Scott Richards, James Earl Jones, Charles S. Dutton, Courtney B. Vance, Michele Shay, Ella Joyce, and others. Keywords: action, black aesthetics, black theatre movement, character, Dutton (Charles S.), event, Hansberry (Lorraine), Henderson (Stephen M.), Molette (Carlton W. and Barbara J.), Richards (Lloyd), Richards (Scott), Richards (Thomas), Jones (James Earl), Joyce (Ella), Vance (Courtney ii B.), Schultz (Michael), Shay (Michele), Stanislavsky (Konstantin), super-objective, theatre, Ward (Douglas Turner), Wilson (August). -

Flashes of Modernity: Stage Design at the Abbey Theatre, 1902- 1966

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Flashes of modernity: stage design at the Abbey Theatre, 1902- 1966 Author(s) McCormack, Christopher Publication Date 2018-08-31 Publisher NUI Galway Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/14988 Downloaded 2021-09-28T08:53:59Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. FLASHES OF MODERNITY: STAGE DESIGN AT THE ABBEY THEATRE, 1902-1966 A Doctoral Thesis Submitted to the O’Donoghue Centre for Drama, Theatre and Performance at National University of Ireland Galway By Christopher McCormack Supervised by Dr. Ian R. Walsh August 2018 2 ABSTRACT Responding to Guy Julier’s call for a “knowing practice” of design studies, this doctoral thesis reveals Ireland’s negotiation with modernity through stage design. I use historian T.J. Clark’s definition of modernity as “contingency,” which “turn[s] from the worship of ancestors and past authorities to the pursuit of a projected future”. Over the course of 60 years that saw the transformation of a pre-industrialised colony to a modernised republic, stage designs offered various possibilities of imagining Irish life. In the same period, the Abbey Theatre’s company shuttled itself from small community halls to the early 19th-century Mechanics’ Theatre, before moving to the commercial Queen’s Theatre, and finally arriving at the modern building that currently houses it. This thesis shines new light on that journey. By investigating the design references outside theatre, we can see how Abbey Theatre productions underlined new ways of envisioning life in Ireland. -

Radiation and the Transmission of Energy: from Stanislavsky to Michael Chekhov

Performance and Spirituality Number 1 (2009) RADIATION AND THE TRANSMISSION OF ENERGY: FROM STANISLAVSKY TO MICHAEL CHEKHOV R. ANDREW WHITE In the first volume of his masterpiece, An Actor’s Work on Himself, Konstantin Stanislavsky cites Ophelia’s speech wherein she confides to Polonius that Hamlet’s strange behavior has frightened her. She recalls: He took me by the wrist and held me hard; Then goes he to the length of all his arm, And with his other hand thus o’er his brow, He falls to such perusal of my face As he would draw it. Long stay’d he so; At last, a little shaking of mine arm And thrice his head thus waving up and down, He raised a sigh so piteous and profound That it did seem to shatter all his bulk And end his being: that done, he lets me go. “Can’t you sense within those lines,” Stanislavsky asks immediately, “a speech which travels through silent communication between Hamlet and Ophelia? Haven’t you noticed, whether in real life or on stage, during mutual communication, sensations of strong-willed currents emanating from you, streaming through your eyes, through your fingertips, through the pores of our body?”1 Then, Stanislavsky struggles to find a single word to define this “internal, invisible, spiritual”2 current of energy, which he deems necessary for actors to transmit during performance either to each other or to the audience. For sending out energy, Stanislavsky proposes the word “radiation” and for receiving energy, he suggests “irradiation.” 3 White 23 Performance and Spirituality Number 1 (2009) Compare the following observation made by Stanislavsky’s star pupil, Michael Chekhov, in his own classic text, On the Technique of Acting. -

Acting and Essence

ACTING AND ESSENCE Experiencing Essence, Presence and Archetype in the Acting Traditions of Stanislavski and Copeau ASHLEY WAIN DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2005 UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN SYDNEY ©Ashley Wai 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to ack owledge my debt to the ma y people who ha,e co tributed this thesis a d the research o which it is based, particularly/ • Those pio eers who first formulated acti g as a serious artform a d spiritual e dea,our i moder Wester theatre. amely Sta isla,ski. 1ichael Chekho,. 1aria 2 ebel. Copeau. Grotowski a d Peter 3rook. a d those who keep this traditio ali,e. i cludi g Le, Dodi . Leco4 a d his artistic desce de ts a d ma y others. Also Sharo Car icke. 3ella 1erli . 6ea 3e edetti. Richard Tar as a d 6orge Ferrer. to whom my research owes a sig ifica t i tellectual debt. a d A.H. Almaas a d Sta isla, Grof. to whom I owe a i estimable i tellectual. spiritual a d perso al debt. To spe d time i the compa y of the writi gs a d practices of such fi e mi ds. a d such e7traordi ary souls. has bee o e of the true pleasures a d pri,ileges of u dertaki g this research. I hope that I here do 8ustice to the traditio s they represe t a d co tribute to the u foldi g life of those traditio s i positi,e ways. • The staff a d stude ts of the Victoria College of the Arts School of Drama. -

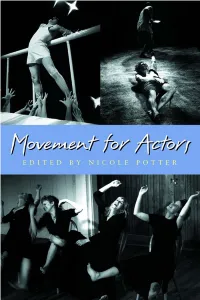

Movement for Actors This Page Intentionally Left Blank Movement for Actors

Movement for Actors This Page Intentionally Left Blank Movement for Actors Edited by NICOLE POTTER © 2002 Nicole Potter The essays in Movement for Actors were written expressly for this book. Copyrights for individual essays are retained by their authors, © 2002. All rights reserved. Copyright under Berne Copyright Convention, Universal Copyright Convention, and Pan-American Copyright Convention. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. 06 05 04 03 02 5 4 3 2 1 Published by Allworth Press An imprint of Allworth Communications, Inc. 10 East 23rd Street, New York, NY 10010 Cover and interior design by Annemarie Redmond Cover photo credits (clockwise, from upper left): Margolis Brown Theater Company, The Bed Experiment, conceived and written by Kari Margolis and Tony Brown, photo: Jim Moore; Theater Ten Ten, King Lear, 1998, directed by Rod McLucas, fight direction by Joe Travers, Jason Hauser (Edmund), Andrew Oswald (Edgar), photo: Sascha Nobés; Shakespeare and Company, Sarah Hickler, Rebecca Perrin, Mary Conway, Susan Dibble, photo: Stephanie Nash. Page composition/typography by Sharp Des!gns, Lansing, MI ISBN: 1-58115-233-7 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Movement for actors / edited by Nicole Potter. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58115-233-7 1. Movement (Acting) I. Potter, Nicole. PN2071.M6 M59 2002 792'.028—dc21 -

Stanislavsky in Context

The S Word: Stanislavsky in Context An International Symposium 5, 6, 7 April 2019 1 2 The Stanislavsky Research Centre Advisory Board Honorary Patron: Anatoly Smeliansky, President, Moscow Art Theatre School Marie-Christine Autant-Mathieu, CNRS, Paris Andrei Malaev Babel, FSU/Asolo Conservatory for Actor Training, USA Sharon Marie Carnicke, University of Southern California, USA Kathy Dacre, Rose Bruford College of Theatre & Performance Jan Hancil, Akademie múzických umění, Prague Bella Merlin, University of California, Riverside, USA Jonathan Pitches, University of Leeds Laurence Senelick, Tufts University, USA David Shirley, Western Australia Academy of Performing Arts/Edith Cowan University Prof. Sergei Tcherkasski, Russian State Institute of Performing Arts Director: Paul Fryer, University of Leeds/London South Bank University Deputy Director: Jonathan Pitches, University of Leeds Stanislavski Studies (Taylor and Francis) Editor in Chief: Paul Fryer, University of Leeds/London South Bank University Editors Julia Listengarten, University of Central Florida, USA Sergei Tcherkasski, Russian State Institute of Performing Arts Luis Campos, Rose Bruford College of Theatre & Performance, UK Reviews Editor: David Matthews, Kings College London Social Media Editor: Michelle LoRicco, Mill Mountain Theatre, USA Consultant Translator: Anna Shulgat, Writers Union of St Petersburg, Russia Editorial Advisory Board Stefan Aquilina, University of Malta, Malta David Chambers, Yale School of Drama, USA Alexander Chepurov, St Petersburg State Theater Arts Academy, Russia Carol Fisher, Sorgenfrei, UCLA, USA Adrian Giurgea, Colgate University, USA Jan Hyvnar, DAMU Prague, Czech Republic Nesta Jones, Rose Bruford College of Theatre and Performance, UK David Krasner, Five Towns College, USA Tomasz Kubikowski, Theatre Academy, Warsaw, Poland Bella Merlin, University of California, Riverside, USA Vladimir Mirodan, University of the Arts, UK. -

The Abbey Theatre Interviews and Recollections in the Same Series

The Abbey Theatre Interviews and Recollections In the same series Morton N. Cohen LEWIS CARROLL: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS Philip Collins (editor) DICKENS: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS (2 volumes) THACKERAY: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS (2 volumes) J. R. Hammond (editor) H. G. WELLS: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS David McLellan (editor) KARL MARX: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS E. H. Mikhail (editor) BRENDAN BEHAN: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS (2 volumes) LADY GREGORY: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS OSCAR WILDE: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS (2 volumes) W. B. YEATS: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS (2 volumes) Harold Orel (editor) KIPLING: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS (2 volumes) Norman Page (editor) BYRON: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS HENRY JAMES: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS D. H. LAWRENCE: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS (2 volumes) TENNYSON: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS. DRJOHNSON: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS R. C. Terry (editor) TROLLOPE: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS Series Standina Order If you would like to receive future titles in this series as they are published, you can make use of our standing order facility. To place a standing order please contact your bookseller or, in case of difficulty, write to us at the address below with your name and address and the name of the series. Please state with which title you wish to begin your standing order. (If you live outside the UK we may not have the rights for your area, in which case we will forward your order to the publisher concerned.) Standing Order Service, Macmillan Distribution Ltd, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, RG212XS, England. THE ABBEY THEATRE Interviews and Recollections Edited by E. H. Mikhail Professor of English University of Lethbridge, Alberta M MACMILLAN PRESS Selection and editorial matter© E. -

Applying Constantin Stanislavski's Acting 'System'

APPLYING CONSTANTIN STANISLAVSKI’S ACTING ‘SYSTEM’ TO CHORAL REHEARSALS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF ARTS BY BOGDAN ANDREI MINUT DISSERTATION ADVISOR: DUANE KARNA BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2009 ii Copyright © 2009 by Bogdan Andrei Minut All rights reserved iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my doctoral committee members, Dr. Duane Karna, Dr. Douglas Amman, Dr. James Helton, Dr. Jody Nagel, and Dr. Elizabeth Bremigan, as well as former committee member Dr. Jeffrey Carter, for their guidance and support throughout my doctoral studies at Ball State University. Special thanks go to Dr. Jeffrey Pappas, former Director of Choral Activities, for his support of my research and for allowing me to work with his student ensemble on this study, to Dr. Kirby Koriath and Dr. Linda Pohly, former and present Coordinators of Graduate Studies in Music, respectively, for their constant care and support, and to Mrs. Linda Elliott for her administrative work. The talented singers of the Ball State University Chamber Choir, including Assistant Director and accompanist (now) Dr. Jill Burleson, and of the Concert Choir played a major role in this research and I want to thank them all for their patience, understanding, and willingness to try something a little different. I would also like to express my deep appreciation for the life, work, and artistry of Constantin Stanislavski who gave so much in particular to the art of the theater but also to all performing arts in general. His vision and ideals of true art are inspiring to me.