Acting and Essence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SS Issue 4 New Master FINAL

Issue #4, May 2014 Contents / Содержание Sergei Tcherkasski (St Petersburg State Theatre Arts Academy, Russia): Inside Sulimov’s Studio: Directors Perform a Play - pg. 4/ Сергей Черкасский (Санкт-Петербургская государственная академия театрального искусства, Россия): «В мастерской М. В. Сулимова: Режиссеры играют спектакль» – с. 26 Peter Zazzali (University of Kansas, U.S.A): An Examination of the Actor’s Double-Consciousness Through Stanislavski’s Conceptualization of ‘Artistic Truth’ - pg. 47/ Питер Заззали (Канзасский университет, США): «Исследование двойственного сознания актера посредством концептуализированной Станиславским идеи ‘сценической правды’» - с. 56 Michael Craig (Copernicus Films, Moscow): Vakhtangov and the Russian Theatre: Making a new documentary film - pg. 66 / Майкл Крэг («Copernicus Films», Москва): «Вахтангов и русский театр. Создание нового документального фильма» – с. 72 Steven Bush (University of Toronto, Canada): George Luscombe and Stanislavski Training in Toronto - pg. 79/ Стивен Буш (Университет Торонто, Канада): «Джордж Ласком и преподавание по методу Станиславского в Торонто» – с. 93 David Chambers (Yale School of Drama): Études in America: A Director’s Memoir - pg. 109/ Дэвид Чемберс (Йельская школа драмы): «Этюды в Америке: Воспоминания режиссера» – с. 126 Eilon Morris (UK) : The Ins and Outs of Tempo-Rhythm - pg. 146 /Эйлон Моррис (Великобритания): «Особенности темпоритма» – с. 159 Martin Julien (University of Toronto) : “Just Be Your Self-Ethnographer”: Reflections on Actors as Anthropologists - pg. -

General Index

General Index Italicized page numbers indicate figures and tables. Color plates are in- cussed; full listings of authors’ works as cited in this volume may be dicated as “pl.” Color plates 1– 40 are in part 1 and plates 41–80 are found in the bibliographical index. in part 2. Authors are listed only when their ideas or works are dis- Aa, Pieter van der (1659–1733), 1338 of military cartography, 971 934 –39; Genoa, 864 –65; Low Coun- Aa River, pl.61, 1523 of nautical charts, 1069, 1424 tries, 1257 Aachen, 1241 printing’s impact on, 607–8 of Dutch hamlets, 1264 Abate, Agostino, 857–58, 864 –65 role of sources in, 66 –67 ecclesiastical subdivisions in, 1090, 1091 Abbeys. See also Cartularies; Monasteries of Russian maps, 1873 of forests, 50 maps: property, 50–51; water system, 43 standards of, 7 German maps in context of, 1224, 1225 plans: juridical uses of, pl.61, 1523–24, studies of, 505–8, 1258 n.53 map consciousness in, 636, 661–62 1525; Wildmore Fen (in psalter), 43– 44 of surveys, 505–8, 708, 1435–36 maps in: cadastral (See Cadastral maps); Abbreviations, 1897, 1899 of town models, 489 central Italy, 909–15; characteristics of, Abreu, Lisuarte de, 1019 Acequia Imperial de Aragón, 507 874 –75, 880 –82; coloring of, 1499, Abruzzi River, 547, 570 Acerra, 951 1588; East-Central Europe, 1806, 1808; Absolutism, 831, 833, 835–36 Ackerman, James S., 427 n.2 England, 50 –51, 1595, 1599, 1603, See also Sovereigns and monarchs Aconcio, Jacopo (d. 1566), 1611 1615, 1629, 1720; France, 1497–1500, Abstraction Acosta, José de (1539–1600), 1235 1501; humanism linked to, 909–10; in- in bird’s-eye views, 688 Acquaviva, Andrea Matteo (d. -

Issue 17 Ausact: the Australian Actor Training Conference 2019

www.fusion-journal.com Fusion Journal is an international, online scholarly journal for the communication, creative industries and media arts disciplines. Co-founded by the Faculty of Arts and Education, Charles Sturt University (Australia) and the College of Arts, University of Lincoln (United Kingdom), Fusion Journal publishes refereed articles, creative works and other practice-led forms of output. Issue 17 AusAct: The Australian Actor Training Conference 2019 Editors Robert Lewis (Charles Sturt University) Dominique Sweeney (Charles Sturt University) Soseh Yekanians (Charles Sturt University) Contents Editorial: AusAct 2019 – Being Relevant .......................................................................... 1 Robert Lewis, Dominique Sweeney and Soseh Yekanians Vulnerability in a crisis: Pedagogy, critical reflection and positionality in actor training ................................................................................................................ 6 Jessica Hartley Brisbane Junior Theatre’s Abridged Method Acting System ......................................... 20 Jack Bradford Haunted by irrelevance? ................................................................................................. 39 Kim Durban Encouraging actors to see themselves as agents of change: The role of dramaturgs, critics, commentators, academics and activists in actor training in Australia .............. 49 Bree Hadley and Kathryn Kelly ISSN 2201-7208 | Published under Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) From ‘methods’ to ‘approaches’: -

MARCH 1St 2018

March 1st We love you, Archivist! MARCH 1st 2018 Attention PDF authors and publishers: Da Archive runs on your tolerance. If you want your product removed from this list, just tell us and it will not be included. This is a compilation of pdf share threads since 2015 and the rpg generals threads. Some things are from even earlier, like Lotsastuff’s collection. Thanks Lotsastuff, your pdf was inspirational. And all the Awesome Pioneer Dudes who built the foundations. Many of their names are still in the Big Collections A THOUSAND THANK YOUS to the Anon Brigade, who do all the digging, loading, and posting. Especially those elite commandos, the Nametag Legionaires, who selflessly achieve the improbable. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – The New Big Dog on the Block is Da Curated Archive. It probably has what you are looking for, so you might want to look there first. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – Don't think of this as a library index, think of it as Portobello Road in London, filled with bookstores and little street market booths and you have to talk to each shopkeeper. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to ~16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. Some links are encoded without a hyperlink to restrict spiderbot activity. You will have to complete the link. Sorry for the inconvenience. Others are encoded but have a working hyperlink underneath. Some are Spoonerisms or even written backwards, Enjoy! ss, @SS or $$ is Send Spaace, m3g@ is Megaa, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. -

LUMBE NEW MILLINERY. Jtjsti*' SALES

a m B errien Co. R ecord. Model W orks, A BEPUBLICAN .NEWSPAPEE. Manufacturers o f all kinds o ij PUBLISHED EVERY THURSDAY. — BT— JO H V G-. BLOIiMES. Call or Writs for Estimates.! T jrm si-SLSO per Ye^r. Furniture & Sewing Machines TiTABtE IX TDVANCR. REPAIRED TO ORDER. VOLUME xvn . BUCHAMN, BERRIEN COUNTY, MICHIGAN, THURSDAY, MARCH 1, 1888. N U M B E R 4 OFFICE—In, Record Building, Oak Street. MAIN ST., BUCHANAN, MIOH. GEKERAILY PERSONA!,. Theological Mathematics. F or Dyspepsia, “That’s easy enough,” said Bawshay. '*■ Pictures b y the Mile. VERSCHIEDENHEIT. “ You keep a fancy store, don’t you ? Business Directory. B usiness Directory* C os tiTen.es Si DECLINED WITH THANKS. Those who have recently had experi A subscriber who has read the Bible Sick Headache, “ Come, while the dew on the meadow, glitters, ‘Well, open up an artificial flower de There is a bill' before the New York IjIARMElis & MANUFACTUREKb BANK, Bu* Come where fhe starlight amiles on the lake." partment; ask the proprietor to let this ence with venders of cheap oiLpaint- more in'seeking a solution of the fol Legislature prohibiting the giving of SOCIETIES. JD chauau, Mich. All butifnesa eiiirusiuu to Cais Chronic Diar Bank will receive prompt aud personal attention. rhoea, Jaundice, “Not mnoh,” she said, “for I don’t like bitters, beauty wait on you; improve the ac ings, who have visited Buchanan, will lowing than ever before, contributes chromos and other presents-to the cus 0 . O. F.—Bnchanan Lodge No. 75 bolds It* And the dew and miasma compel m eto take. -

The Australian Theatre Family

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship A Chance Gathering of Strays: the Australian theatre family C. Sobb Ah Kin MA (Research) University of Sydney 2010 Contents: Epigraph: 3 Prologue: 4 Introduction: 7 Revealing Family 7 Finding Ease 10 Being an Actor 10 Tribe 15 Defining Family 17 Accidental Culture 20 Chapter One: What makes Theatre Family? 22 Story One: Uncle Nick’s Vanya 24 Interview with actor Glenn Hazeldine 29 Interview with actor Vanessa Downing 31 Interview with actor Robert Alexander 33 Chapter Two: It’s Personal - Functioning Dysfunction 39 Story Two: “Happiness is having a large close-knit family. In another city!” 39 Interview with actor Kerry Walker 46 Interview with actor Christopher Stollery 49 Interview with actor Marco Chiappi 55 Chapter Three: Community −The Indigenous Family 61 Story Three: Who’s Your Auntie? 61 Interview with actor Noel Tovey 66 Interview with actor Kyas Sheriff 70 Interview with actor Ursula Yovich 73 Chapter Four: Director’s Perspectives 82 Interview with director Marion Potts 84 Interview with director Neil Armfield 86 Conclusion: A Temporary Unity 97 What Remains 97 Coming and Going 98 The Family Inheritance 100 Bibliography: 103 Special Thanks: 107 Appendix 1: Interview Information and Ethics Protocols: 108 Interview subjects and dates: 108 • Sample Participant Information Statement: 109 • Sample Participant Consent From: 111 • Sample Interview Questions 112 2 Epigraph: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Everything was in confusion in the Oblonsky’s house. The wife had discovered that the husband was carrying on an intrigue with a French girl, who had been a governess in their family, and she had announced to her husband that she could not go on living in the same house with him. -

Picturing France

Picturing France Classroom Guide VISUAL ARTS PHOTOGRAPHY ORIENTATION ART APPRECIATION STUDIO Traveling around France SOCIAL STUDIES Seeing Time and Pl ace Introduction to Color CULTURE / HISTORY PARIS GEOGRAPHY PaintingStyles GOVERNMENT / CIVICS Paris by Night Private Inve stigation LITERATURELANGUAGE / CRITICISM ARTS Casual and Formal Composition Modernizing Paris SPEAKING / WRITING Department Stores FRENCH LANGUAGE Haute Couture FONTAINEBLEAU Focus and Mo vement Painters, Politics, an d Parks MUSIC / DANCENATURAL / DRAMA SCIENCE I y Fontainebleau MATH Into the Forest ATreebyAnyOther Nam e Photograph or Painting, M. Pa scal? ÎLE-DE-FRANCE A Fore st Outing Think L ike a Salon Juror Form Your Own Ava nt-Garde The Flo ating Studio AUVERGNE/ On the River FRANCHE-COMTÉ Stream of Con sciousness Cheese! Mountains of Fra nce Volcanoes in France? NORMANDY “I Cannot Pain tan Angel” Writing en Plein Air Culture Clash Do-It-Yourself Pointillist Painting BRITTANY Comparing Two Studie s Wish You W ere Here Synthétisme Creating a Moo d Celtic Culture PROVENCE Dressing the Part Regional Still Life Color and Emo tion Expressive Marks Color Collectio n Japanese Prin ts Legend o f the Château Noir The Mistral REVIEW Winds Worldwide Poster Puzzle Travelby Clue Picturing France Classroom Guide NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON page ii This Classroom Guide is a component of the Picturing France teaching packet. © 2008 Board of Trustees of the National Gallery of Art, Washington Prepared by the Division of Education, with contributions by Robyn Asleson, Elsa Bénard, Carla Brenner, Sarah Diallo, Rachel Goldberg, Leo Kasun, Amy Lewis, Donna Mann, Marjorie McMahon, Lisa Meyerowitz, Barbara Moore, Rachel Richards, Jennifer Riddell, and Paige Simpson. -

Chelsea Boy Dies Friday Following 2-Car Crash Recycle Chelsea

#m'**#**#*CAR-RT-!:>0RT**nR3 1476 10/1/89 U 23 McKune Memorial Library •$# 221 S. Main St, Che I sear MI 48118 QUOTE "A man travels the world c over in search #of what he 35 needs and returns home to find it." per copy y ONE HUNDRED-NINETEENTH YEAR—No. 7 CHELSEA, MICHIGAN, WEDNESDAY, JULY \% 1989 24 Pages This Week y Recycle Chelsea •am Alreadyin Danger as m. Funds Dry Up Chelsea's recycling program, which materials are being hauled away and level and should be up to the local began late last year, could be out of the distance from each station to, units of government. Look at it this business by the end of the month Recycle Ann Arbor. Glass and cans way, if you were going to continue a m unless local governmental agencies have become the most profitable recycling service with a big company, pi come to its rescue. items as the state is staring at a someone would have to pay for it. It's "Recycle Chelse'a," the village's newspaper glut, making newspaper got to be paid for one way or another. participation in the Washtenaw worth almost nothing, which in And it could cost as much or more to county-wide recycling program, ap creases the cost of the program even get rid of garbage through recycling parently will need an infusion of more. However, the newspaper sec than the way we've always done it." money in order to survive. The county tion of the bin is always the first to fill Village president Jerry Satter plans to stop picking up the recycling up and it would be hard to justify pick thwaite, who has strongly supported bin in Polly's Market, as well as in its ing up a bin that is mostly full of wor setting up a local, independent recycl other sites around the county, in thless newspaper. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

A Proposal for an Integrated Rehearsal Methodology for Shakespeare (And Others) Combining Active Analysis and Viewpoints

“UNPACK MY HEART WITH WORDS”: A Proposal for an Integrated Rehearsal Methodology for Shakespeare (and Others) Combining Active Analysis and Viewpoints by GERALD P. SKELTON, JR. BSc, MFA, MA A practice-based thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences of Kingston University in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2016 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Gerald P. Skelton, Jr. ABSTRACT The performance of Shakespeare represents a distinct challenge for actors versed in the naturalistic approach to acting as influenced by Stanislavsky. As John Barton suggests, this tradition is not readily compatible with the language-based tradition of Elizabethan players. He states that playing Shakespeare constitutes a collision of “the Two Traditions” (1984, p. 3). The current training-based literature provides many guidelines on analysing and speaking dramatic verse by Shakespeare and others, but few texts include practical ways for contemporary performers to embrace both traditions specifically in a rehearsal context. This research seeks to develop a new actor-centred rehearsal methodology to help modern theatre artists create performances that balance the spontaneity and psychological insight that can be gained from a Stanislavsky-based approach with the textual clarity necessary for Shakespearean drama, and a physical rigour which, I will argue, helps root the voice within the body. The thesis establishes what practitioner Patsy Rodenburg (2005, p. 3) refers to as the need for words, or the impulse to respond to events primarily through language, as the key challenge that contemporary performers steeped in textual naturalism confront when approaching Shakespeare and other classical playwrights. -

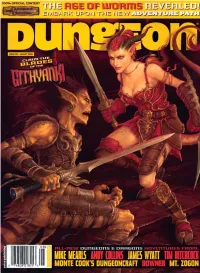

Dungeon Magazine #125.Pdf

#125 MAP & HANDOUT SUPPLEMENT PRODUCED BY PAIZO PUBLISHING, LLC. WWW.PAIZO.COM Joachim Barrum THE THREE FACES OF EVIL By Mike Mearls Clues discovered in Diamond Lake lead to the Dark Cathedral, a forlorn chamber hid- den below a local mine. There the PCs battle the machinations of the Ebon Triad, a cult dedicated to three vile gods. What does the Ebon Triad know about the Age of Worms, and why are they so desperate to get it started? An Age of Worms Adventure Path scenario for 3rd-level characters. Dungeon #125 Map & Handout Supplement © 2005 Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Permission to photocopy for personal use only. All rights reserved. 1 DUNGEON 125 Supplement Theldrick Ragnolin Eva Widermann Dourstone Eva Widermann Dungeon #125 Map & Handout Supplement © 2005 Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Permission to photocopy for personal use only. All rights reserved. 2 DUNGEON 125 Supplement The Faceless One Grallak Kur Eva Widermann Steve Prescott Dungeon #125 Map & Handout Supplement © 2005 Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Permission to photocopy for personal use only. All rights reserved. 3 DUNGEON 125 Supplement Steve Prescott Horshoe Area 17 Caverns 5 ft. Area 14 Robert Lazzaretti Robert Lazzaretti Dungeon #125 Map & Handout Supplement © 2005 Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Permission to photocopy for personal use only. All rights reserved. 4 DUNGEON 125 Supplement Caves of Erythnul 12 N KKKK 13 A G 18 A 14 17 15 16 One square = 5 feet Robert Lazzaretti Robert Lazzaretti Grimlock Cavern 19 up 18 20 down N 21 One square = 5 feet Robert Lazzaretti Robert Lazzaretti Dungeon #125 Map & Handout Supplement © 2005 Wizards of the Coast, Inc. -

Sugar Babies - the Quintessential Burlesque Show

SEPTEMBER,1986 Vol 10 No 8 ISSN 0314 - 0598 A publication of the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust Sugar Babies - The Quintessential Burlesque Show personality and his own jokes. Not all the companies, however, lived up to the audience's expectations; the comedians were not always brilliant and witty, the girls weren't always beautiful. This proved to be Ralph Allen's inspiration for SUGAR BABIES. "During the course of my research, one question kept recurring. Why not create a quintessen tial Burlesque Show out of authentic materials - a show of shows as I have played it so often in the theatre of my mind? After all, in a theatre of the mind, nothing ever disappoints. " After running for seven years in America - both in New York and on tour - the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust will mount SUGAR BABIES in Australia, opening in Sydney at Her Majesty's Theatre on October 30. In February it will move to Melbourne and other cities, including Adelaide, Perth and Auckland. The tour is expected to last about 39 weeks. Eddie Bracken, who is coming from the USA to star in the role of 1st comic in SUGAR BABIES, received rave reviews from critics in the USA. "Bracken, with his rolling eyes, rubber face and delightful slow burns, is the consummate performer, " said Jim Arpy in the Quad City Times. Since his debut in 1931 on Broadway, Bracken has appeared in Sugar Babies from the original New York production countless movies and stage shows. Garry McDonald will bring back to life one of Harry Rigby, happened to be at the con Australia's greatest comics by playing his SUGAR BABIES, conceived by role as "Mo" (Roy Rene).