Issue 17 Ausact: the Australian Actor Training Conference 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert Lepage's Scenographic Dramaturgy: the Aesthetic Signature at Work

1 Robert Lepage’s Scenographic Dramaturgy: The Aesthetic Signature at Work Melissa Poll Abstract Heir to the écriture scénique introduced by theatre’s modern movement, director Robert Lepage’s scenography is his entry point when re-envisioning an extant text. Due to widespread interest in the Québécois auteur’s devised offerings, however, Lepage’s highly visual interpretations of canonical works remain largely neglected in current scholarship. My paper seeks to address this gap, theorizing Lepage’s approach as a three-pronged ‘scenographic dramaturgy’, composed of historical-spatial mapping, metamorphous space and kinetic bodies. By referencing a range of Lepage’s extant text productions and aligning elements of his work to historical and contemporary models of scenography-driven performance, this project will detail how the three components of Lepage’s scenographic dramaturgy ‘write’ meaning-making performance texts. Historical-Spatial Mapping as the foundation for Lepage’s Scenographic Dramaturgy In itself, Lepage’s reliance on evocative scenography is inline with the aesthetics of various theatre-makers. Examples range from Appia and Craig’s early experiments summoning atmosphere through lighting and minimalist sets to Penny Woolcock’s English National Opera production of John Adams’s Dr. Atomic1 which uses digital projections and film clips to revisit the circumstances leading up to Little Boy’s release on Hiroshima in 1945. Other artists known for a signature visual approach to locating narrative include Simon McBurney, who incorporates digital projections to present Moscow via a Google Maps perspective in Complicité’s The Master and Margarita and auteur Benedict Andrews, whose recent production of Three Sisters sees Chekhov’s heroines stranded on a mound of dirt at the play’s conclusion, an apt metaphor for their dreary futures in provincial Russia. -

Community Engagement in Independent Performance-Making in Australia: a Case Study of Rovers

THEMED ARTiclE Community Engagement in Independent Performance-making in Australia: A case study of Rovers KATHRYN KELLY AND EMILY COLEMAN This article offers a perspective on strategies for community engagement by independent performance-makers and cultural institutions in Australia today. Beginning with an overview of community engagement in Australian performance, the article then describes a specific case- study drawn from personal practice: Belloo Creative’s Rovers which was a new performance work based on the lives of its performers, Roxanne MacDonald and Barbara Lowing. As part of the production of Rovers, Belloo Creative, working with young Aboriginal artist Emily Coleman, trialled a community engagement project to welcome Aboriginal audiences to the 2018 Brisbane Festival. The article includes a personal reflection on Rovers that interleaves the commentary of Emily and Kathryn as the two artists who lead the community engagement project, and concludes by suggesting some key considerations for other independent companies who might wish to engage with community. Community Engagement and Australian Performance ommunity engagement is a broad term that Queensland across the last decade. QMF regularly Cembraces a diverse range of activities and practices commissions large-scale community engagement projects across sectors and disciplines in contemporary Australia, such as Boomtown in Gladstone in 2013, where a musical as noted in the introduction for this special edition of was co-created with the participation of 300 community Social Alternatives. Community engagement in the arts members and performed to an audience of over 20,000 is broadly defined by the Australia Council, the national (Carter and Heim 2015: 202). Community engagement funding organisation for arts and culture, as covering: projects are also now routinely showcased within the major programs of city-based festivals, for example, The [A]ll the ways that artists and arts organisations Good Room’s I’ve Been Meaning to Ask You: a work can connect with communities. -

The Australian Theatre Family

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship A Chance Gathering of Strays: the Australian theatre family C. Sobb Ah Kin MA (Research) University of Sydney 2010 Contents: Epigraph: 3 Prologue: 4 Introduction: 7 Revealing Family 7 Finding Ease 10 Being an Actor 10 Tribe 15 Defining Family 17 Accidental Culture 20 Chapter One: What makes Theatre Family? 22 Story One: Uncle Nick’s Vanya 24 Interview with actor Glenn Hazeldine 29 Interview with actor Vanessa Downing 31 Interview with actor Robert Alexander 33 Chapter Two: It’s Personal - Functioning Dysfunction 39 Story Two: “Happiness is having a large close-knit family. In another city!” 39 Interview with actor Kerry Walker 46 Interview with actor Christopher Stollery 49 Interview with actor Marco Chiappi 55 Chapter Three: Community −The Indigenous Family 61 Story Three: Who’s Your Auntie? 61 Interview with actor Noel Tovey 66 Interview with actor Kyas Sheriff 70 Interview with actor Ursula Yovich 73 Chapter Four: Director’s Perspectives 82 Interview with director Marion Potts 84 Interview with director Neil Armfield 86 Conclusion: A Temporary Unity 97 What Remains 97 Coming and Going 98 The Family Inheritance 100 Bibliography: 103 Special Thanks: 107 Appendix 1: Interview Information and Ethics Protocols: 108 Interview subjects and dates: 108 • Sample Participant Information Statement: 109 • Sample Participant Consent From: 111 • Sample Interview Questions 112 2 Epigraph: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Everything was in confusion in the Oblonsky’s house. The wife had discovered that the husband was carrying on an intrigue with a French girl, who had been a governess in their family, and she had announced to her husband that she could not go on living in the same house with him. -

Teacher's Notes 2007

Sydney Theatre Company and Sydney Festival in association with Perth International Festival present the STC Actors Company in The War of the Roses by William Shakespeare Teacher's Resource Kit Part One written and compiled by Jeffrey Dawson Acknowledgements Thank you to the following for their invaluable material for these Teachers' Notes: Laura Scrivano, Publications Manager,STC; Tom Wright, Associate Director, STC Copyright Copyright protects this Teacher’s Resource Kit. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited. However, limited photocopying for classroom use only is permitted by educational institutions. Sydney Theatre Company The Wars of the Roses Teachers Notes © 2009 1 Contents Production Credits 3 Background information on the production 4 Part One, Act One Backstory & Synopsis 5 Part One, Act Two Backstory & Synopsis 5 Notes from the Rehearsal Room 7 Shakespeare’s History plays as a genre 8 Women in Drama and Performance 9 The Director – Benedict Andrews 10 Review Links 11 Set Design 12 Costume Design 12 Sound Design 12 Questions and Activities Before viewing the Play 14 Questions and Activities After viewing the Play 20 Bibliography 24 Background on Part Two of The War of the Roses 27 Sydney Theatre Company The Wars of the Roses Teachers Notes © 2009 2 Sydney Theatre Company and Sydney Festival in association with Perth International Festival present the STC Actors Company in The War of the Roses by William Shakespeare Cast Act One King Richard II Cate Blanchett Production -

Remembering Edouard Borovansky and His Company 1939–1959

REMEMBERING EDOUARD BOROVANSKY AND HIS COMPANY 1939–1959 Marie Ada Couper Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne 1 ABSTRACT This project sets out to establish that Edouard Borovansky, an ex-Ballets Russes danseur/ teacher/choreographer/producer, was ‘the father of Australian ballet’. With the backing of J. C. Williamson’s Theatres Limited, he created and maintained a professional ballet company which performed in commercial theatre for almost twenty years. This was a business arrangement, and he received no revenue from either government or private sources. The longevity of the Borovansky Australian Ballet company, under the direction of one person, was a remarkable achievement that has never been officially recognised. The principal intention of this undertaking is to define Borovansky’s proper place in the theatrical history of Australia. Although technically not the first Australian professional ballet company, the Borovansky Australian Ballet outlasted all its rivals until its transformation into the Australian Ballet in the early 1960s, with Borovansky remaining the sole person in charge until his death in 1959. In Australian theatre the 1930s was dominated by variety shows and musical comedies, which had replaced the pantomimes of the 19th century although the annual Christmas pantomime remained on the calendar for many years. Cinemas (referred to as ‘picture theatres’) had all but replaced live theatre as mass entertainment. The extremely rare event of a ballet performance was considered an exotic art reserved for the upper classes. ‘Culture’ was a word dismissed by many Australians as undefinable and generally unattainable because of our colonial heritage, which had long been the focus of English attitudes. -

Laist Gets a Lot of Event Announcements, and We Comb Through Them All to Bring You a Curated List of What’S Happening in LA This Weekend, Including These 16 Events

Weekend Planner: 16 Things To Do In Los Angeles There's a 'Lost' reunion at PaleyFest on Sunday. (Photo: ABC/Lost) LAist gets a lot of event announcements, and we comb through them all to bring you a curated list of what’s happening in LA this weekend, including these 16 events. Now, no more excuses...so get out there and play. Don’t forget to check out other picks in our monthly column, too. Read on for all the details. FRIDAY, MARCH 14 TV TALK: PaleyFest 2014 has a great slate of programming this weekend, beginning with the cast of Orange Is the New Black at 7 pm at the Dolby Theater in Hollywood. OITNB cast includes Taylor Schilling, Jason Biggs, Laura Prepon, Natasha Lyonne, Kate Mulgrew, Danielle Brooks, Uzo Aduba, Taryn Manning, Yael Stone, Laverne Cox, Michael Harney, Lorraine Toussaint and Jenji Kohan, creator & executive producer. 7 pm. Tickets: $25-75+ fees. [Saturday’s show is How I Met Your Mother and Sunday’s show is the 10th Anniversary and Lost reunion. FILM: Jacques Demy’s 1964 French New Wave musical The Umbrellas of Cherbourg screens at the Nuart for its 50th anniversary revival with a new digital restoration. At the 7:30 pm show, actor George Chakiris (who starred in The Young Girls of Rochefort, a collaboration with Demy, actress Catherine Deneuve and composer Michel Legrand) introduces the film and discusses his collaborations with Debra Levine, blogger of artsmeme.com. The film screens through March 20. STORYTELLING: Beth Lapides (of UnCabaret) hosts Say the Word: The New Me, a night of comedic storytelling about “rebirth and reinvention” at the Skirball. -

Chloe Armstrong

JOSH MCCONVILLE | Actor FILM Year Production / Character Director Company 2017 1% Stephen McCallum Head Gear Films Skink 2016 WAR MACHINE David Michôd Porchlight Films Payne 2015 JOE CINQUE'S CONSOLATION Sotiris Dounoukos Consolation Productions Chris 2014 DOWN UNDER Abe Forsythe Riot Films Gav 2013 THE INFINITE MAN Hugh Sullivan Infinite Man Productions P/L Dean Trilby 2012 THE TURNING “COMMISSION” David Wenham ArenaMedia Vic Lang TELEVISION Year Production/Character Director Company 2017 HOME & AWAY Various Seven Network Caleb 2015 CLEVERMAN Wayne Blair ABCTV Dickson 2013 THE KILLING FIELD Samantha Lang Seven Network Operations Jackson 2012 REDFERN NOW Various ABC TV/Blackfella Films Photographer Shanahan Management Pty Ltd Level 3 | Berman House | 91 Campbell Street | Surry Hills NSW 2010 PO Box 1509 | Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia | ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 | Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 | [email protected] 2011 WILD BOYS Various Southern Star Productions No. 8 Ben 2009 UNDERBELLY II: Various Screentime A TALE OF TWO CITIES Hurley THEATRE Year Production/Character Director Company 2017 CLOUD 9 Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Clive/Cathy 2016 A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Bottom 2016 ALL MY SONS Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company George Deever 2016 HAY FEVER Imara Savage Sydney Theatre Company Sandy Tyrell 2016 ARCADIA Richard Cottrell Sydney Theatre Company Bernard Nightingale 2015 HAMLET Damien Ryan Bell Shakespeare Hamlet 2015 AFTER DINNER Imara Savage Sydney Theatre Company -

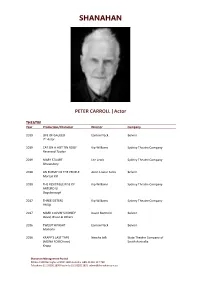

PETER CARROLL |Actor

SHANAHAN PETER CARROLL |Actor THEATRE Year Production/Character Director Company 2019 LIFE OF GALILEO Eamon Flack Belvoir 7th Actor 2019 CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Reverend Tooker 2019 MARY STUART Lee Lewis Sydney Theatre Company Shrewsbury 2018 AN ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Morton Kiil 2018 THE RESISTIBLE RISE OF Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company ARTURO UI Dogsborough 2017 THREE SISTERS Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Phillip 2017 MARK COLVIN’S KIDNEY David Berthold Belvoir David, Bruce & Others 2016 TWELFTH NIGHT Eamon Flack Belvoir Malvolio 2016 KRAPP’S LAST TAPE Nescha Jelk State Theatre Company of (MONA FOMO tour) South Australia Krapp Shanahan Management Pty Ltd PO Box 1509 Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 [email protected] SHANAHAN 2015 SEVENTEEN Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Tom 2015 KRAPP’S LAST TAPE Nescha Jelk State Theatre Company of Krapp South Australia 2014 CHRISTMAS CAROL Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Marley and Other 2014 OEDIPUS REX Adena Jacobs Belvoir Oedipus 2014 NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTIAN Matthew Lutton Malthouse Theatre Mr Hugo Sword 2012-13 CHITTY CHITTY BANG BANG Roger Hodgman TML Enterprises Grandpa Potts 2012 OLD MAN Anthea Williams B Sharp Belvoir (Downstairs) Albert 2011 NO MAN’S LAND Michael Gow QTC/STC Spooner 2011 DOCTOR ZHIVAGO Des McAnuff Gordon Frost Organisation Alexander 2010 THE PIRATES OF PENZANCE Stuart Maunder Opera Australia Major-General Stanley 2010 KING LEAR Marion Potts Bell -

Sugar Babies - the Quintessential Burlesque Show

SEPTEMBER,1986 Vol 10 No 8 ISSN 0314 - 0598 A publication of the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust Sugar Babies - The Quintessential Burlesque Show personality and his own jokes. Not all the companies, however, lived up to the audience's expectations; the comedians were not always brilliant and witty, the girls weren't always beautiful. This proved to be Ralph Allen's inspiration for SUGAR BABIES. "During the course of my research, one question kept recurring. Why not create a quintessen tial Burlesque Show out of authentic materials - a show of shows as I have played it so often in the theatre of my mind? After all, in a theatre of the mind, nothing ever disappoints. " After running for seven years in America - both in New York and on tour - the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust will mount SUGAR BABIES in Australia, opening in Sydney at Her Majesty's Theatre on October 30. In February it will move to Melbourne and other cities, including Adelaide, Perth and Auckland. The tour is expected to last about 39 weeks. Eddie Bracken, who is coming from the USA to star in the role of 1st comic in SUGAR BABIES, received rave reviews from critics in the USA. "Bracken, with his rolling eyes, rubber face and delightful slow burns, is the consummate performer, " said Jim Arpy in the Quad City Times. Since his debut in 1931 on Broadway, Bracken has appeared in Sugar Babies from the original New York production countless movies and stage shows. Garry McDonald will bring back to life one of Harry Rigby, happened to be at the con Australia's greatest comics by playing his SUGAR BABIES, conceived by role as "Mo" (Roy Rene). -

Download (2MB)

This file is part of the following reference: Carless, Victoria Leigh (2008) Making invisible pathways visible : case studies of Shadow Play and The Rainbow Dark. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/3565 Making Invisible Pathways Visible Case Studies of Shadow Play and The Rainbow Dark A thesis submitted with creative work in fulfilment of the requirement for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at James Cook University by VICTORIA LEIGH CARLESS B. Theatre (Hons) School of Creative Arts 2008 STATEMENT OF SOURCES: DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own my work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and list of references if given. ………………………………… ………………………………… (Victoria Carless) (Date) ii STATEMENT OF ACCESS I, the undersigned, the author of this work, understand that James Cook University will make this thesis available for use within the University Library, and via the Australian Digital Theses network, for use elsewhere. I understand that, as an unpublished work, a thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act and I do not wish to place any further restriction on access to this work. ………………………………… ………………………………… (Victoria Carless) (Date) iii ELECTRONIC COPY OF THESIS FOR LIBRARY DEPOSIT DECLARATION I, the undersigned, the author of this work, declare that the electronic copy of this thesis provided to the James Cook University Library is an accurate copy of the print thesis submitted, within the limits of the technology available. -

ANGEL DEANGELIS Hair Stylist IATSE 798

ANGEL DEANGELIS Hair Stylist IATSE 798 FILM HUSTLERS Department Head Director: Lorene Scafaria Cast: Constance Wu, Lili Reinhart, Julia Stiles, Trace Lysette PRIVATE LIFE Department Head Director: Tamara Jenkins SHOW DOGS Department Head – Las Vegas Shoot Director: Raja Gosnell Natasha Lyonne, Will Arnett COLLATERAL BEAUTY Department Head Director: David Frankel Cast: Helen Mirren, Ed Norton, Keira Knightley THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN 2 Department Head Director: Marc Webb Cast: Dane DeHaan THE HEAT Department Head Director: Paul Feig Cast: Melissa McCarthy MUHAMMAD ALI’S GREATEST FIGHT Department Head Director: Stephen Frears Cast: Christopher Plummer, Benjamin Walker, Frank Langella JACK REACHER Department Head Director: Christopher McQuarrie Cast: Rosamund Pike, Robert Duvall, Richard Jenkins, Werner Herzog, Jai Courtney, Joseph Sikora, GODS BEHAVING BADLY Department Head Director: Marc Turtletaub Cast: Alicia Silverstone, Edie Falco, Ebon Moss-Bachrach, Oliver Platt, Christopher Walken, Rosie Perez, Phylicia Rashad THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN Department Head Director: Marc Webb Cast: Embeth Davidtz THE MILTON AGENCY 6715 Hollyw ood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Angel DeAngelis Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsim ile: 323.460.4442 Hair inquiries@m iltonagency.com www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 5 NEW YEAR’S EVE Department Head Director: Garry Marshall Cast: Jessica Biel, Zac Efron, Cary Elwes, Alyssa Milano, Carla Gugino, Jon Bon Jovi, Sofia Vergara, Lea Michele, James Belushi, Abigail Breslin, Josh Duhamel, Cherry Jones THE SITTER Department Head -

ORANGE IS the NEW BLACK Season 1 Cast List SERIES

ORANGE IS THE NEW BLACK Season 1 Cast List SERIES REGULARS PIPER – TAYLOR SCHILLING LARRY BLOOM – JASON BIGGS MISS CLAUDETTE PELAGE – MICHELLE HURST GALINA “RED” REZNIKOV – KATE MULGREW ALEX VAUSE – LAURA PREPON SAM HEALY – MICHAEL HARNEY RECURRING CAST NICKY NICHOLS – NATASHA LYONNE (Episodes 1 – 13) PORNSTACHE MENDEZ – PABLO SCHREIBER (Episodes 1 – 13) DAYANARA DIAZ – DASCHA POLANCO (Episodes 1 – 13) JOHN BENNETT – MATT MCGORRY (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) LORNA MORELLO – YAEL MORELLO (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13) BIG BOO – LEA DELARIA (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) TASHA “TAYSTEE” JEFFERSON – DANIELLE BROOKS (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13) JOSEPH “JOE” CAPUTO – NICK SANDOW (Episodes 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) YOGA JONES – CONSTANCE SHULMAN (Episodes 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) GLORIA MENDOZA – SELENIS LEYVA (Episodes 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13) S. O’NEILL – JOEL MARSH GARLAND (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13) CRAZY EYES – UZO ADUBA (Episodes 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) POUSSEY – SAMIRA WILEY (Episodes 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13) POLLY HARPER – MARIA DIZZIA (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12) JANAE WATSON – VICKY JEUDY (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) WANDA BELL – CATHERINE CURTIN (Episodes 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 13) LEANNE TAYLOR – EMMA MYLES (Episodes 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13) NORMA – ANNIE GOLDEN (Episodes 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13) ALEIDA DIAZ – ELIZABETH RODRIGUEZ