Copy, Transform, Combine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kitchen Center for Video, Music and Dance

THE KITCHEN CENTER FOR VIDEO, MUSIC AND DANCE December 29, 1979 Woody,Steina Vasulka 257 Franklin Street Buffalo, New York 14202 Dear Woody and Steina, Enclosed is a rough draft of the videotape catalogue we're trying to put together . A few tapes are listed under your name . Could you please look over this information and make corrections, exclamations and changes where necessary . I would like to have your changes or OK by the end of February if possible . Thanks for the trouble . Board of Directors Robert Ashley Paula Cooper Suzanne Delehanty Philip Glass Barbara London Mary MacArthur Barbara Pine Carlota Schoolman Robert Stearns John Stewart Caroline Thorne Paul Walter HALEAKALA, INC. 59 WOOSTER NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10012 (212) 925-3615 ARTIST ADDRESS PHONE NAME OF TAPE CORRECTIONS/ADDITIONS SUGGESTIONS ARTIST (S) TITLEUS) TIME Ga n m r 0 0 0 cc w r a m wm AARON , Jane and When I Was A Worker Like LaVerne r 0 r n rt N~ x n a0 n BLUMBERG , Skip 29 minutes 0 w 0 K A straightforward account of both management and labor at a w rr Sears and Roebuck Company mail order house in Chicago . The m m plant foreman explains some of the operations of the business n with a tour through the nine floor structure, spotted along m with interviews with workers at a variety of duties, who appear to genuinely enjoy their labors . x R X X x Note : Copy #1 ACCONCI , Vito Red Tapes 140 minutes I, Common Knowledge Picture plane space - novelistic - scheme of detective story . -

Story the Viewp

Unpublished Notes on the Viewpoint of Story Based on the Work of Mary Overlie Wendell Beavers (Copyright 2000) Story The Viewpoint of Story has a particular provenance which is rooted in a moment of dance history which declared itself anti-story, anti literal and anti illusion.* Several of the most powerful storytelling experiences in the theater I ever witnessed were performances of the Grand Union, a group made up of participants of the Judson Dance Theater. Its members were perceived as both heroic and legendary performers and disgusting cheapeners of the magic that was supposed to happen in the theater. The divide was mostly generational and the result of a natural sort of overthrow of what came before. Their brand of open improvisational performance featured precipitous surprises and a kind of high drama difficult to explain because of the ordinary circumstances from which these events always managed somehow to arise. The next “thing” to happen always seemed inevitable after the fact, but completely impossible to anticipate the moment before. This was storytelling--which got labeled post-modern--but in retrospect had a peculiar link to shamanistic story telling. It may be jarring to link post modernism with shamanism because we associate shamanism with the cultivation and communication of spiritual or other worldly things. Postmodern performers of the sixties and seventies were looking into themselves and their immediate environment. They were communicating or pointing out the nature of the material world before us. There was not supposed to be anything otherworldly about it. The ordinary magic that they practiced and bequeathed to the next generation was quite subversive to the modern dance sensibility, not to mention the high art theater world of ballet etc. -

Barbara Dilley & Yvonne Rainer with Wendy Perron

Danspace Project Conversations Without Walls: Barbara Dilley & Yvonne Rainer with Wendy Perron November 21, 2020 Judy Hussie-Taylor Welcome to Danspace Project and our Conversation Without Walls. I'm Judy Hussie-Taylor, Executive Director & Chief Curator. I'm honored to welcome three people I hold in high esteem, Barbara Dilley, Yvonne Rainer, and Wendy Perron. Thank you all for joining us today to celebrate Wendy's new book "The Grand Union: Accidental Anarchists of Downtown Dance 1970-76" published by Wesleyan University Press. So this is an exciting occasion. I just quickly want to thank our Danspace staff and our behind the scenes wizards, especially Yolanda Royster and Ben Kimitch, for holding us all together today on the Zoom. So all three of our guests have extensive histories with Danspace Project. Barbara Dilley co-founded Danspace Project, along with Mary Overlie and Larry Fagin in 1974. Prior to that, Barbara was a member of Merce Cunningham's company from 1963 to 1968. She danced with Yvonne Rainer from 1966 to 1970 and was a member of the Grand Union, which you'll hear a lot about today. She was instrumental in the founding of Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado, which is where I met Barbara. She designed the dance department and served as the University's President from 1985 to 1993. Most recently, she is the author of "This Perfect Moment, Teaching Thinking Dancing," which is part autobiography, part workbook. Choreographer, filmmaker, and the author of many books, Yvonne Rainer was a co-founding member of Judson Dance Theater in 1962. -

A Proposal for an Integrated Rehearsal Methodology for Shakespeare (And Others) Combining Active Analysis and Viewpoints

“UNPACK MY HEART WITH WORDS”: A Proposal for an Integrated Rehearsal Methodology for Shakespeare (and Others) Combining Active Analysis and Viewpoints by GERALD P. SKELTON, JR. BSc, MFA, MA A practice-based thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences of Kingston University in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2016 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Gerald P. Skelton, Jr. ABSTRACT The performance of Shakespeare represents a distinct challenge for actors versed in the naturalistic approach to acting as influenced by Stanislavsky. As John Barton suggests, this tradition is not readily compatible with the language-based tradition of Elizabethan players. He states that playing Shakespeare constitutes a collision of “the Two Traditions” (1984, p. 3). The current training-based literature provides many guidelines on analysing and speaking dramatic verse by Shakespeare and others, but few texts include practical ways for contemporary performers to embrace both traditions specifically in a rehearsal context. This research seeks to develop a new actor-centred rehearsal methodology to help modern theatre artists create performances that balance the spontaneity and psychological insight that can be gained from a Stanislavsky-based approach with the textual clarity necessary for Shakespearean drama, and a physical rigour which, I will argue, helps root the voice within the body. The thesis establishes what practitioner Patsy Rodenburg (2005, p. 3) refers to as the need for words, or the impulse to respond to events primarily through language, as the key challenge that contemporary performers steeped in textual naturalism confront when approaching Shakespeare and other classical playwrights. -

Reflections on Nancy Stark Smith, Collaborating Founder of Contact Improvisation, Part 1 by Jonathan Stein

Photo: Ilya Domanov Reflections on Nancy Stark Smith, Collaborating Founder of Contact Improvisation, part 1 by Jonathan Stein Internationally known dancer, editor, writer, organizer and a collaborating founder of Contact Improvisation, Nancy Stark Smith, died on May 1st after an extraordinary life of fearlessly exploring new ways of making art, breaking gender norms, and communicating the ephemeral body-mind states of experiences of dance. She was in the initial group working with Steve Paxton, who originated Contact Improvisation, along with Nita Little, Daniel Lepkoff, Barbara Dilley, Mary Fulkerson, and Nancy Topf, among others. Influenced by the ground-breaking dance-theater experiments in improvisation of the Grand Union and Judson Dance Theater, she ignited a new revolution after the first public performance of Contact Improvisation in New York City in 1972 by propagating the work world-wide in a myriad of ways. In 1975, she co-founded with Lisa Nelson Contact Quarterly, a Vehicle for Moving Ideas, which has become a critical international journal on improvisation and somatics. In 1990, Nancy created the Underscore, a long-form dance improvisation structure that incorporated Contact Improvisation into a broader arena of improvisational dance practice. The Underscore is practiced around the world, including at the Global Underscore in June every year since 2000. She also developed her pedagogy, the States of Grace, which involved twelve arenas (“Pods”) of dance experience. Since her death CQ has created a Facebook page for remembrances, Nancy Stark Smith Harvest and a website, Honoring Nancy Stark Smith; and Dance Magazine has published Wendy Perron’s obituary. thINKingDANCE has invited movement artists, writers and others who knew Stark Smith or were influenced by her across the generations to offer their reflections. -

Letter to the Editor

Letter to Nominated for the Bueno the Editor Prize awarded by Dance Perspectives A Correction Foundation I would like to point out an error in the De La Torre. Fall 1992 issue of DRJ. In the report on the Society of Dance History Scholars THE GRAND UNION (1970-1976) Conference, Marge Maddux states that An Improvisational Performance Group the productions of BronislavaNijinska's By Margaret Hupp Ramsay. Ph.D. Les Noces and Les Biches were recon- An intimate view of a revolutionary moment in structed by Frank Ries for the Oakland American dance and theater history. The New Ballet (p. 59). These works were York-based improvisational collective - Yvonne mounted on the Oakland Ballet by the Rainer, Steve Paxton, David Gordon, Trisha Brown, choreographer's daughter, Irina Douglas Dunn, Barbara Dilley and Nancy Green. Nijinska; Ries was only responsible for the staging of Le Train Bleu. "... and the audience stood and clapped with tears running down their cheeks and I thought, 'I guess Lynn Garafola that was funny.' I had goose bumps all over me." New York, New York Dr. Ramsay holds a Ph.D. in Performance Studies from New York University and an M.S. in Dance from the University of Wisconsin. PETER LANG PUBLISHING 62 West 45th Street. 4th Floor. N.Y.. N.Y. 10036 To order call 212/764-1471 Degrees: B.A., B.S., M.A., M.F.A. in Choreography and/or Performance, Ph.D. in Dance and Related Arts (Coeducational at the Graduate Level). Scholarships and Graduate Teaching Assistantships Available SUMMERDANCE '93: Truth in Movement: Phenomenology and Dance, Sondra Fraleigh, June 7-25; Modern Dance and Partnering Workshop with Art Bridgman and Myma Packer, June 7-19; Historical and Contemporary Jazz Styles with Danny Buraczeski, July 5- 17; Curriculum Inquiry in Dance and the Related Arts, May 17-June 4, Dr. -

An Historical Perspective on Lucinda Childs' Calico Mingling

arts Article Towards an Embodied Abstraction: An Historical Perspective on Lucinda Childs’ Calico Mingling (1973) Lou Forster 1,2 1 Centre de Recherche sur les Arts et le Langage, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, 75006 Paris, France; [email protected] 2 Institut National D’histoire de L’art, 75002 Paris, France Abstract: In the 1970s, choreographer Lucinda Childs developed a reductive form of abstraction based on graphic representations of her dance material, walking, and a specific approach towards its embodiment. If her work has been described through the prism of minimalism, this case study on Calico Mingling (1973) proposes a different perspective. Based on newly available archival documents in Lucinda Childs’s papers, it traces how track drawing, the planimetric representation of path across the floor, intersected with minimalist aesthetics. On the other hand, it elucidates Childs’s distinctive use of literacy in order to embody abstraction. In this respect, the choreographer’s approach to both dance company and dance technique converge at different influences, in particular modernism and minimalism, two parallel histories which have been typically separated or opposed. Keywords: reading; abstraction; minimalism; technique; collaboration; embodiment; geometric abstraction; modernism 1. Introduction On the 7 December 1973, at the Whitney Museum of American Art, four women Citation: Forster, Lou. 2021. performed Calico Mingling, the latest group piece by Lucinda Childs. The soles of white Towards an Embodied Abstraction: sneakers, belonging to Susan Brody, Judy Padow, Janice Paul and Childs, resonated on the An Historical Perspective on Lucinda wood floor of the Madison Avenue, building with a sustained tempo. -

Judson Dance Theater: the Work Is Never Done ABOUT the EXHIBITION MOVING-IMAGE INSTALLATION DESIGNED by CHARLES ATLAS

Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done ABOUT THE EXHIBITION MOVING-IMAGE INSTALLATION DESIGNED BY CHARLES ATLAS ******************************** ******************************** The exhibition is organized by Ana Janevski, Curator, and Thomas J. Lax, Associate For a brief period in the early For this exhibition, filmmaker and Curator, with Martha Joseph, 1960s, a group of choreographers, video artist Charles Atlas has Curatorial Assistant, Department of Media and Performance Art. visual artists, composers, and made an installation of historical Performances are produced filmmakers gathered in Judson moving-image material related to by Lizzie Gorfaine, Producer, Memorial Church, a socially engaged the work of the choreographers with Kate Scherer, Manager, Performance and Live Programs. Protestant congregation in New featured in the performance York’s Greenwich Village, for a program, alternating with a series of workshops that ultimately compilation of performance footage redefined what counted as dance. from the Judson group’s various The performances that evolved members. It includes footage of The exhibition is made possible by Hyundai Card. from these workshops incorporated both individual and group pieces everyday movements—gestures drawn made during the Judson era and Leadership support is provided from the street or the home; their after, emphasizing the relationship by Monique M. Schoen Warshaw, The Jill and Peter Kraus Endowed structures were based on games, of the soloist to the ensemble and Fund for Contemporary simple tasks, and social dances. showing how Judson influenced the Exhibitions, and by MoMA’s Wallis Spontaneity and unconventional later careers of these artists. To Annenberg Fund for Innovation in Contemporary Art through the methods of composition were create the segment dedicated to Annenberg Foundation. -

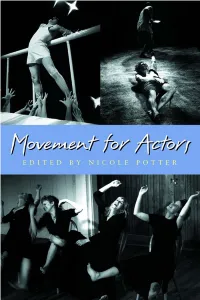

Movement for Actors This Page Intentionally Left Blank Movement for Actors

Movement for Actors This Page Intentionally Left Blank Movement for Actors Edited by NICOLE POTTER © 2002 Nicole Potter The essays in Movement for Actors were written expressly for this book. Copyrights for individual essays are retained by their authors, © 2002. All rights reserved. Copyright under Berne Copyright Convention, Universal Copyright Convention, and Pan-American Copyright Convention. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. 06 05 04 03 02 5 4 3 2 1 Published by Allworth Press An imprint of Allworth Communications, Inc. 10 East 23rd Street, New York, NY 10010 Cover and interior design by Annemarie Redmond Cover photo credits (clockwise, from upper left): Margolis Brown Theater Company, The Bed Experiment, conceived and written by Kari Margolis and Tony Brown, photo: Jim Moore; Theater Ten Ten, King Lear, 1998, directed by Rod McLucas, fight direction by Joe Travers, Jason Hauser (Edmund), Andrew Oswald (Edgar), photo: Sascha Nobés; Shakespeare and Company, Sarah Hickler, Rebecca Perrin, Mary Conway, Susan Dibble, photo: Stephanie Nash. Page composition/typography by Sharp Des!gns, Lansing, MI ISBN: 1-58115-233-7 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Movement for actors / edited by Nicole Potter. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58115-233-7 1. Movement (Acting) I. Potter, Nicole. PN2071.M6 M59 2002 792'.028—dc21 -

Yvonne Rainer Papers, 1871-2013, Bulk 1959-2013

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt0b69r6kc Online items available Finding aid for the Yvonne Rainer papers, 1871-2013, bulk 1959-2013 Martha Steele Finding aid for the Yvonne Rainer 2006.M.24 1 papers, 1871-2013, bulk 1959-2013 Descriptive Summary Title: Yvonne Rainer papers Date (inclusive): 1871-2013 (bulk 1959-2013) Number: 2006.M.24 Creator/Collector: Rainer, Yvonne, 1934- Physical Description: 146 Linear Feet(222 boxes, 12 flatfile folders) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Yvonne Rainer is an avant-garde American dancer, choreographer, filmmaker and writer. Her papers document her life as an artist from the late 1950s through 2013, and include photographic material dated as early as 1933. Materials include dance scores; programs and posters; photographic and audiovisual documentation of performances, rehearsals, and films; correspondence; writings, including Rainer's feature-length film scripts; and critical response to her work. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note Choreographer, dancer, filmmaker and writer, Yvonne Rainer is celebrated as a pioneer of postmodern dance. Her often experimental and challenging work, continuously produced for more than forty years, has been widely influential. Rainer was born in San Francisco in 1934. In 1956 she moved to New York with painter Al Held to study acting, but the following year began studying dance instead. -

Barbara Dilley Contemplative Dance Practice: a Dancer’S Meditation Hall/A Meditator’S Dance Hall

Pre-Conference Workshop July 25 to July 26, 2017 Barbara Dilley Contemplative Dance Practice: A Dancer’s Meditation Hall/A Meditator’s Dance Hall Pre-Conference Workshop July 26 to July 27, 2017 Jens Johannsen Embodying Flow Main Conference July 27 to 30, 2017 Nina Martin, Plenary Session Wendell Beavers and Andrea Olsen, Featured Presenters This conference serves as a laboratory/research/workshop setting. While the setting is organized and spon- sored by the Body-Mind Centering Association, vetted sessions are offered both by BMC professionals and by non-BMC professionals, and occasionally by highly qualified students. The designation of “P” after a presenter’s name in the program booklet indicates that the presenter is a BMCA Certified Professional. The Body-Mind Centering Association, as sponsor of this conference, cannot control, and disclaims any respon- sibility for, the content of individual programs, including without limitation terms used in individual presentations or in published materials furnished as part of a participant’s presentation. Presenters are expected to abide by any service mark, ethical, or scholarly obligations pertaining to their presented modality. NOTE: Alexander Technique™, Bartenieff Fundamentals™, Body-Mind Centering®, Bones for Life®, Dynamic Embodiment®, Feldenkrais Method®, Fluid Strength Yoga Practice™, GYROKINESIS®, GYROTONIC®, and most other somatic practice names are legally registered and trademarked. They are used here, with permission, with that understanding. 2 Welcome from the BMCA President We are deeply grateful to LeAnne Smith and her commitment to the tenet that one role of the academy, as we pursue in BMC, is to facilitate inquiry. We are here because of her desire to support this work that has had such an influence on the field of dance, her students, and herself. -

Save Pdf (0.44

In Memory Mary Overlie 1946–2020 Blackboard — Hand — Stone On the day I met Mary Overlie in the summer of 2004, I sat enraptured (if befuddled) as she stood before her iconic blackboard and lectured on the approach to theatre that she orig- inated and developed since the 1970s: The Viewpoints. On the board, she had written the names of The Viewpoints’ six materials: Space, Shape, Time, Emotion, Movement, and Story. Below them were her chalk drawings representing The Viewpoints’ foundational principles: six squares to show “solid state theatre” and its “deconstruction”; the “vertical” tower of classicism and modernism collapsing to the “horizontal” assemblage of postmodernism; and the circle of “reification,” her name for the artists’ process of moving concepts, ideas, forms, and percep- tions from the unknown to the known and back again. Then, she flipped the board to reveal her drawing of “The Bridge,” with its nine supportive frames for Viewpoints study, which led from “News of a Difference” to “The Original Anarchist.” About an hour into her lecture, Mary extended her arm to gaze inquisitively at her hand. After some time, she said, “Any moment this will become art. This is The Viewpoints.” After years of talking with Mary, writing about her, teaching The Viewpoints, and creating perfor- mances through her work, I’ve come to understand the greater significance of my friend and mentor’s simple act. For me, it speaks to who Mary Overlie was, as a Bessie Award–winning choreographer, dancer, teacher, theorist, and comrade. What she taught with that gesture was the quiet confidence she modeled for her students through her life, art, and teaching.