Fortifying Or Fragmenting the State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ceasefires Sans Peace Process in Myanmar: the Shan State Army, 1989–2011

Asia Security Initiative Policy Series Working Paper No. 26 September 2013 Ceasefires sans peace process in Myanmar: The Shan State Army, 1989–2011 Samara Yawnghwe Independent researcher Thailand Tin Maung Maung Than Senior Research Fellow Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) Singapore Asia Security Initiative Policy Series: Working Papers i This Policy Series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed are entirely the author’s own and not that of the Centre for Non-Traditional Security (NTS) Studies, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS). The paper is an outcome of a project on the topic ‘Dynamics for Resolving Internal Conflicts in Southeast Asia’. This topic is part of a broader programme on ‘Bridging Multilevel and Multilateral Approaches to Conflict Prevention and Resolution’ under the Asia Security Initiative (ASI) Research Cluster ‘Responding to Internal Crises and Their Cross Border Effects’ led by the RSIS Centre for NTS Studies. The ASI is supported by the MacArthur Foundation. Visit http://www.asicluster3.com to learn more about the Initiative. More information on the work of the RSIS Centre for NTS Studies can be found at http://www.rsis.edu.sg/nts. Terms of use You are free to publish this material in its entirety or only in part in your newspapers, wire services, internet-based information networks and newsletters and you may use the information in your radio-TV discussions or as a basis for discussion in different fora, provided full credit is given to the author(s) and the Centre for Non-Traditional Security (NTS) Studies, S. -

Inside Trained to Torture

TRAINED TO TORTURE Systematic war crimes by the Burma Army in Ta’ang areas of northern Shan State (March 2011 - March 2016) z f; kifu mi GHeftDyfkefwt By Ta'ang Women's Organization (TWO) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to express special thanks to all the victims and the communities who contributed their voices and evidence for the report by sharing their testimonies and also giving their time and energy to inform this report. Special thanks extended to the Burma Relief Center (BRC) for their financial support and supporting the volunteer to edit the translation of this report. We would like to thank all the individuals and organizations who assisted us with valuable input in the process of producing the “Trained to Torture” report, including friends who drawing maps for the report and layout and also the Palaung people as a whole for generously helping us access grassroots area which provided us with invaluable information for this report. TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary 1 Methodology 4 Background 5 Burma Army expansion and spread of conflict in Ta’ang areas 7 Continued reliance on local militia to “divide and rule” 9 Ta’ang exclusion from the peace process 11 Analysis of human rights violations by the Burma Army in Ta’ang areas (March 2011 - March 2016) 12 • Torture 14 - Torture and killing of Ta’ang prisoners of war 16 - Torture by government-allied militia 17 • Extrajudicial killing of civilians 18 • Sexual violence 19 • Shelling, shooting at civilian targets 20 • Forced portering, use of civilians as human shields 22 • Looting and deliberate -

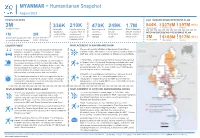

Myanmar – Humanitarian Snapshot (August 2021)

MYANMAR – Humanitarian Snapshot August 2021 PEOPLE IN NEED 2021 HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE PLAN 3M 336K 210K 470K 249K 1.7M 944K $276M $97M (35%) People targeted Requirements Received People in need Internally People internally Non-displaced Returnees and Other vulnerable displaced displaced due to stateless locally people, mostly in INTERIM EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN 1M 2M people at the clashes and persons in integrated urban and peri- start of 2021 Rakhine people urban areas people previously identified people identified insecurity since 2M $109M $17M (15%) February 2021 in conflict-affected areas since 1 February People targeted Requirements Received COUNTRYWIDE DISPLACEMENT IN KACHIN AND SHAN A total of 3 million people are targeted for humanitarian The overall security situation in Kachin and Shan states assistance across the country. This includes 1 million remains volatile, with various level of clashes reported between people in need in conflict-affected areas previously MAF and ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) or among EAOs. identified and a further 2 million people since 1 February. Monsoon flash floods affected around 125,000 people in In Shan State, small-scale population movement was reported the regions and states of Kachin, Kayin, Mandalay, Mon, in Hsipaw, Muse, Kyethi and Mongkaing townships since mid- Rakhine, eastern Shan and Tanintharyi between late July July. In total, 24,950 people have been internally displaced and mid-August, according to local actors. Immediate across Shan State since the start of 2021; over 5,000 people needs of families affected or evacuated have been remain displaced in five townships. addressed by local aid workers and communities. In Kachin, no new displacement has been reported. -

Shan State - Myanmar

Myanmar Information Management Unit SHAN STATE - MYANMAR Mohnyin 96°40'E Sinbo 97°30'E 98°20'E 99°10'E 100°0'E 100°50'E 24°45'N 24°45'N Bhutan Dawthponeyan India China Bangladesh Myo Hla Banmauk KACHIN Vietnam Bamaw Laos Airport Bhamo Momauk Indaw Shwegu Lwegel Katha Mansi Thailand Maw Monekoe Hteik Pang Hseng (Kyu Koke) Konkyan Cambodia 24°0'N Muse 24°0'N Muse Manhlyoe (Manhero) Konkyan Namhkan Tigyaing Namhkan Kutkai Laukkaing Laukkaing Mabein Tarmoenye Takaung Kutkai Chinshwehaw CHINA Mabein Kunlong Namtit Hopang Manton Kunlong Hseni Manton Hseni Hopang Pan Lon 23°15'N 23°15'N Mongmit Namtu Lashio Namtu Mongmit Pangwaun Namhsan Lashio Airport Namhsan Mongmao Mongmao Lashio Thabeikkyin Mogoke Pangwaun Monglon Mongngawt Tangyan Man Kan Kyaukme Namphan Hsipaw Singu Kyaukme Narphan Mongyai Tangyan 22°30'N 22°30'N Mongyai Pangsang Wetlet Nawnghkio Wein Nawnghkio Madaya Hsipaw Pangsang Mongpauk Mandalay CityPyinoolwin Matman Mandalay Anisakan Mongyang Chanmyathazi Ai Airport Kyethi Monghsu Sagaing Kyethi Matman Mongyang Myitnge Tada-U SHAN Monghsu Mongkhet 21°45'N MANDALAY Mongkaing Mongsan 21°45'N Sintgaing Mongkhet Mongla (Hmonesan) Mandalay Mongnawng Intaw international A Kyaukse Mongkaung Mongla Lawksawk Myittha Mongyawng Mongping Tontar Mongyu Kar Li Kunhing Kengtung Laihka Ywangan Lawksawk Kentung Laihka Kunhing Airport Mongyawng Ywangan Mongping Wundwin Kho Lam Pindaya Hopong Pinlon 21°0'N Pindaya 21°0'N Loilen Monghpyak Loilen Nansang Meiktila Taunggyi Monghpyak Thazi Kenglat Nansang Nansang Airport Heho Taunggyi Airport Ayetharyar -

Mimu875v01 120626 3W Livelihoods South East

Myanmar Information Management Unit 3W South East of Myanmar Livelihoods Border and Country Based Organizations Presence by Township Budalin Thantlang 94°23'EKani Wetlet 96°4'E Kyaukme 97°45'E 99°26'E 101°7'E Ayadaw Madaya Pangsang Hakha Nawnghkio Mongyai Yinmabin Hsipaw Tangyan Gangaw SAGAING Monywa Sagaing Mandalay Myinmu Pale .! Pyinoolwin Mongyang Madupi Salingyi .! Matman CHINA Ngazun Sagaing Tilin 1 Tada-U 1 1 2 Monghsu Mongkhet CHIN Myaing Yesagyo Kyaukse Myingyan 1 Mongkaung Kyethi Mongla Mindat Pauk Natogyi Lawksawk Kengtung Myittha Pakokku 1 1 Hopong Mongping Taungtha 1 2 Mongyawng Saw Wundwin Loilen Laihka Ü Nyaung-U Kunhing Seikphyu Mahlaing Ywangan Kanpetlet 1 21°6'N Paletwa 4 21°6'N MANDALAY 1 1 Monghpyak Kyaukpadaung Taunggyi Nansang Meiktila Thazi Pindaya SHAN (EAST) Chauk .! Salin 4 Mongnai Pyawbwe 2 Tachileik Minbya Sidoktaya Kalaw 2 Natmauk Yenangyaung 4 Taunggyi SHAN (SOUTH) Monghsat Yamethin Pwintbyu Nyaungshwe Magway Pinlaung 4 Mawkmai Myothit 1 Mongpan 3 .! Nay Pyi Hsihseng 1 Minbu Taw-Tatkon 3 Mongton Myebon Langkho Ngape Magway 3 Nay Pyi Taw LAOS Ann MAGWAY Taungdwingyi [(!Nay Pyi Taw- Loikaw Minhla Nay Pyi Pyinmana 3 .! 3 3 Sinbaungwe Taw-Lewe Shadaw Pekon 3 3 Loikaw 2 RAKHINE Thayet Demoso Mindon Aunglan 19°25'N Yedashe 1 KAYAH 19°25'N 4 Thandaunggyi Hpruso 2 Ramree Kamma 2 3 Toungup Paukkhaung Taungoo Bawlakhe Pyay Htantabin 2 Oktwin Hpasawng Paungde 1 Mese Padaung Thegon Nattalin BAGOPhyu (EAST) BAGO (WEST) 3 Zigon Thandwe Kyangin Kyaukkyi Okpho Kyauktaga Hpapun 1 Myanaung Shwegyin 5 Minhla Ingapu 3 Gwa Letpadan -

5-Year Strategic Development Plan, 2018-2022 Pa-O Self-Administered Zone Shan State, Republic of the Union of Myanmar

5-Year Strategic Development Plan, 2018-2022 Pa-O Self-Administered Zone Shan State, Republic of the Union of Myanmar A PROSPEROUS COMMUNITY FOR THIS AND FUTURE VOLUME II: DEVELOPMENT PROPOSALS GENERATIONS Myanmar Institute for Integrated Development 12, Kanbawza Street, Bahan Township Yangon, Myanmar [email protected] | www.mmiid.org Author | Paul Knipe Contributors | Victoria Garcia, Mike Haynes, U Yae Htut, Qingrui Huang, Jolanda Jonkhart, Joern Kristensen, Daw Khin Yupar Kyaw, U Ko Lwin, Daw Hsu Myat Myint Lwin, U Myint Lwin, Daw Thet Htar Myint, U Nay Linn Oo, Samuel Pursch, Barbara Schott, Dr Khin Thawda Shein, U Kyaw Thein, Daw Nilar Win Yangon, August 2018 Cover image | Participant from the Pa-O Women’s Union at the Evaluation and Strategy Workshop TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations .........................................................................................................................I Map of the Pa-O SAZ ..........................................................................................................II Introduction ...........................................................................................................................1 1. Infrastructure ...................................................................................................................2 Map 1: Hopong Township village road upgrade ...................................................3 Map 2: Hsihseng Township village road upgrade ................................................4 Map 3: Pinlaung Township village road upgrade .................................................5 -

Pangolin Trade in the Mong La Wildlife Market and the Role of Myanmar in the Smuggling of Pangolins Into China

Global Ecology and Conservation 5 (2016) 118–126 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global Ecology and Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gecco Original research article Pangolin trade in the Mong La wildlife market and the role of Myanmar in the smuggling of pangolins into China Vincent Nijman a, Ming Xia Zhang b, Chris R. Shepherd c,∗ a Oxford Wildlife Trade Research Group, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK b Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Gardens, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Mengla, China c TRAFFIC, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia article info a b s t r a c t Article history: We report on the illegal trade in live pangolins, their meat, and their scales in the Special Received 7 November 2015 Development Zone of Mong La, Shan State, Myanmar, on the border with China, and Received in revised form 18 December 2015 present an analysis of the role of Myanmar in the trade of pangolins into China. Mong Accepted 18 December 2015 La caters exclusively for the Chinese market and is best described as a Chinese enclave in Myanmar. We surveyed the morning market, wildlife trophy shops and wild meat restaurants during four visits in 2006, 2009, 2013–2014, and 2015. We observed 42 bags Keywords: of scales, 32 whole skins, 16 foetuses or pangolin parts in wine, and 27 whole pangolins for Burma CITES sale. Our observations suggest Mong La has emerged as a significant hub of the pangolin Conservation trade. The origin of the pangolins is unclear but it seems to comprise a mixture of pangolins Manis from Myanmar and neighbouring countries, and potentially African countries. -

The Union Report the Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Census Report Volume 2

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report The Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Volume Report : Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 1: Map of Myanmar by State, Region and District Census Report Volume 2 (Union) i Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is my hope that the main census results will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and Offices at all administrative levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

December 2008

cover_asia_report_2008_2:cover_asia_report_2007_2.qxd 28/11/2008 17:18 Page 1 Central Committee for Drug Lao National Commission for Drug Office of the Narcotics Abuse Control Control and Supervision Control Board Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 500, A-1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43 1) 26060-0, Fax: (+43 1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org Opium Poppy Cultivation in South East Asia Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand OPIUM POPPY CULTIVATION IN SOUTH EAST ASIA IN SOUTH EAST CULTIVATION OPIUM POPPY December 2008 Printed in Slovakia UNODC's Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme (ICMP) promotes the development and maintenance of a global network of illicit crop monitoring systems in the context of the illicit crop elimination objective set by the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Drugs. ICMP provides overall coordination as well as direct technical support and supervision to UNODC supported illicit crop surveys at the country level. The implementation of UNODC's Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme in South East Asia was made possible thanks to financial contributions from the Government of Japan and from the United States. UNODC Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme – Survey Reports and other ICMP publications can be downloaded from: http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/crop-monitoring/index.html The boundaries, names and designations used in all maps in this document do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. This document has not been formally edited. CONTENTS PART 1 REGIONAL OVERVIEW ..............................................................................................3 -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Grave Diggers a Report on Mining in Burma

GRAVE DIGGERS A REPORT ON MINING IN BURMA BY ROGER MOODY CONTENTS Abbreviations........................................................................................... 2 Map of Southeast Asia............................................................................. 3 Acknowledgments ................................................................................... 4 Author’s foreword ................................................................................... 5 Chapter One: Burma’s Mining at the Crossroads ................................... 7 Chapter Two: Summary Evaluation of Mining Companies in Burma .... 23 Chapter Three: Index of Mining Corporations ....................................... 29 Chapter Four: The Man with the Golden Arm ....................................... 43 Appendix I: The Problems with Copper.................................................. 53 Appendix II: Stripping Rubyland ............................................................. 59 Appendix III: HIV/AIDS, Heroin and Mining in Burma ........................... 61 Appendix IV: Interview with a former mining engineer ........................ 63 Appendix V: Observations from discussions with Burmese miners ....... 67 Endnotes .................................................................................................. 68 Cover: Workers at Hpakant Gem Mine, Kachin State (Photo: Burma Centrum Nederland) A Report on Mining in Burma — 1 Abbreviations ASE – Alberta Stock Exchange DGSE - Department of Geological Survey and Mineral Exploration (Burma) -

PEACE Info (March 29, 2018)

PEACE Info (March 29, 2018) − UWSA angered by government’s statement on its NCA stance − Northern Alliance Seeks Continued Support From China in Peace Process Negotiations − Coalition of ethnic armed groups ready to join Panglong summit, awaits invite − If the government officially invited, FPNCC will attend the 21st Century Panglong Conference − Karen Nationals Thahaya Association urges Tatmadaw and KNU to follow NCA on Hpapun issue − RCSS/SSA-S wants negotiation with TNLA once more − Army Brings Case Against Relative of 2 Kachin Villagers Allegedly Killed by Soldiers − Displaced residents in Kyaukme are scared to return home despite fighting stopped − MYANMAR’S REFUGEE AND IDP: Shan dislocation and dispossession after three decades − Burma’s army chief congratulates president-elect − Tough challenges lie ahead for President U Win Myint − Can A New President Pull Myanmar Out of the Quagmire of Conflict? − အစိုးရက ဖိတ္ၾကားပါက ေျမာက္ပိုင္းလက္နက္ကိုင္ ၇ ဖြဲ႔ ၿငိမ္းခ်မ္းေရးညီလာခံ တက္မည္ − ၂၁ရာစု ပင္လုံတတိယအႀကိမ္ အစည္းအေဝးဖိတ္ရင္ FPNCC တက္မယ္ − ေျမာက္ပိုင္းလက္နက္ကိုင္ခုနစ္ဖြဲ႕ ၂၁ ရာစုပင္လံုတတိယအစည္းအေဝး တက္ေရာက္မည္ − တရား၀င္ ဖိတ္ၾကားပါက ၂၁ ပင္လံုသိုု႔ FPNCC အဖြဲ႔စံု တက္ေရာက္မည္ − FPNCC လက္နက္ကိုင္ ၇ဖဲြ႔ ၂၁ရာစု ပင္လံုတတိယ အစည္းအေ၀းဖိတ္ရင္ တက္ဖို႕ဆုံးျဖတ္ − အစိုးရက တရား၀င္ဖိတ္လာပါက၂၁ ပင္လံုတက္မည္ဟု FPNCC ဆို − ေျမာက္ပိုင္း မဟာမိတ္အဖြဲ႕မ်ား ၂၁ ရာစုပင္လုံတက္ရန္ ဆုံးျဖတ္ − ၿငိမ္းခ်မ္းေရးလုပ္ငန္းစဥ္ ေရွ႕ဆက္ႏုိင္ေရး စုိးရိမ္မႈမ်ားေလွ်ာ့ခ်ရန္ RCSS အႀကံေပးတိုက္တြန္း − KNU တြဲဖက္ အေထြေထြအတြင္းေရးမႉး(၂) ပဒိုေစာလွထြန္းႏွင့္ ေတြ႔ဆံုေမးျမန္းျခင္း − RCSS/SSA