The Guest Worker Myth How Turkish Immigrant Communities Rebuilt West Berlin 1960S - 1980S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bezirksprofil Tempelhof-Schöneberg (07)

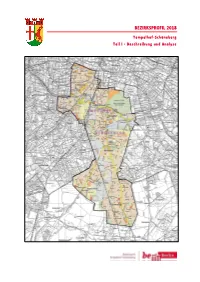

BEZIRKSPROFIL 2018 Tempelhof-Schöneberg Teil I - Beschreibung und Analyse Impressum Herausgebend: Bezirksamt Tempelhof-Schöneberg von Berlin Koordination: Ulrich Binner (SPK DK), Tel.: (030) 90277-6651 Bildnachweis: SPK DK oder wie angegeben Bearbeitungsstand: beschlossen durch AG SRO am 18.08.2018 beschlossen durch Bezirksamt Tempelhof-Schöneberg am 18.12.2018 Datenstand: KID & DGZ 12/2016, ergänzende Daten wie angegeben Inhaltsverzeichnis 0 Vorbemerkungen .......................................................................................................... 1 0.1 Aufbau und Gliederung .................................................................................................................................... 1 0.2 Ergänzungen und erweiterte Auswertungen ................................................................................................. 2 1 Portrait des Bezirks und seiner Bezirksregionen .............................................................. 3 1.1 Schöneberg Nord (070101) .............................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Schöneberg Süd (070202) ................................................................................................................................ 7 1.3 Friedenau (070303) .......................................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Tempelhof (070404) ..................................................................................................................................... -

Regulating Foreign Labor in Emerging Economies: Between National Objectives and International Commitments

E-ISSN 2281-4612 Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Vol 10 No 3 May 2021 ISSN 2281-3993 www.richtmann.org . Research Article © 2021 Aries Harianto. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) Received: 25 September 2020 / Accepted: 9 April 2021 / Published: 10 May 2021 Regulating Foreign Labor in Emerging Economies: Between National Objectives and International Commitments Aries Harianto Universitas Jember, Jalan Kalimantan No. 37, Kampus Tegal Boto, Jember, Jawa Timur 68121, Indonesia DOI: https://doi.org/10.36941/ajis-2021-0092 Abstract The dialectics of the regulation of foreign workers, is a problematic indication as a legal problem in Indonesian legislation. This article aims to describe the urgency of critical studies concerning the regulation of foreign workers by exploring existing legal problems with national commitments to ratify international agreements regarding free trade, with a case study in Indonesia. By using normative and juridical approach with a variety of approaches both the law approach, conceptual approach, case approach and comparative approach, the study found that the regulation there is an inconsistency clause regarding special competencies that must be owned by foreign workers, including the selection and use of terminology in Act No. 13 of 2003 concerning Manpower. Thus, this study offers a constitutional solution due to the regulation of the subordinate foreign workers on international trade commitments which in turn negate the constitutional goals of creating the welfare of domestic workers. The normative consequences that immediately bind Indonesia after integrating itself in the World Trade Organization (WTO) membership are services trade agreements that are contained in the regulations of the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). -

The Migration Phenomenon in East Asia: Towards a Theological Response from God's People As a Host Community

The migration phenomenon in East Asia: Towards a theological response from God's people as a host community [Published by Regnum in 2015 as: Theologising Migration: Otherness and Liminality in East Asia] Paul Woods This dissertation is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Theology) of AGST Alliance 2012 I declare that this dissertation is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a qualification at any tertiary education institution. Paul Woods.................................................................................... Abstract This dissertation works towards a theological response from the East Asian church to intra-regional migration. It provides an introduction to migration theory and the experiences of people on the move, as the basis of a theological reflection. Migration is a significant part of modern life, and the Asian church has begun to respond and reach out to migrants. However, this concern for the Other (someone different and distinct from oneself) is patchy and lacks robust theological foundations. Migration brings those in the host countries face to face with racial and social Others, who may face ill-treatment and exploitation, to which the church is sometimes perceived as indifferent. The principal motifs employed in the work are Otherness and liminality. Through these, this research explores the commandments in the Pentateuch which require fair treatment of the alien in Israel. A similar approach is applied to Christ’s life and teaching and the example of the early church in the New Testament. The same motifs of Otherness and liminality are used to examine the status of God’s followers before Him and other nations. -

Arizona's SB 1070 As a National Lightning

S.B 1070 as a National Lightning Rod Arizona’s S.B. 1070 as a National Lightning Rod CYNTHIA BURNS* The passage of Arizona’s Senate Bill 1070 in 2010, called the Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act, has unleashed a political debate on illegal immigration in our country. This contentious State Bill, SB 1070, authorized law enforcers to identify, prosecute and deport illegal immigrants. Anti-immigration advocates hailed the bill for its tough stance on illegal immigration whereas proponents of immigration reform derided the law for its potential to discriminate Hispanic communities. Additionally, the bill created a rift between state and federal government on immigration reform, primarily raised questions about states right to write its own immigration laws preempting federal power. This has resulted in legal cases challenging the constitutionality of the law in the Federal Courts. The legal question raised by Arizona’s immigration law, SB 1070, was if states, Arizona in this case, had the purview to pass immigration legislation believed to be preempted by the authority granted by the Constitution to the federal government. In a split decision, the United States Supreme Court, in Arizona v United States, struck down three of the four challenged provisions of the bill for interfering with federal policy and remanded one-the provision authorizing police to check alien registration papers- to the lower courts. The Supreme Court ruling garnered national headlines particularly the provision in S.B. 1070’s Section 3 that created a state misdemeanor for the “willful failure to complete or carry an alien registration document” (S. -

Immigration Reform: What's Next for Agriculture?

Immigration Reform: What’s Next for Agriculture? Philip Martin arm labor was a major concern the employer saw work-identification of agriculture in the early 1980s, documents. Employers are not required About 5% of U.S. workers, and over when enforcement of immigra- to determine the authenticity of the 50% of the workers employed on F tion laws involved the Border Patrol documents presented by workers. U.S. crop farms are unauthorized. driving into fields and attempting to There were two legalization pro- This article explains how immigration apprehend workers who ran away. grams in 1987–88 that allowed 2.7 reforms in the past increased the availability of unauthorized farm Apprehended migrants were normally million unauthorized foreigners, 85% workers, allowing employers to returned to Mexico, and many made of whom were Mexicans, to become become complacent about farm their way back to the farms on which legal immigrants. The nonfarm pro- labor. However, federal government they were employed within days. There gram legalized 1.6 million unauthor- audits of employers, and more states were no fines on employers who know- ized foreigners who had been in the requiring employers to use the federal ingly hired unauthorized workers, and United States since January 1, 1982, E-Verify database to check the legal the major enforcement risk was loss of while the Special Agricultural Worker status of new hires, have increased production until unauthorized work- (SAW) program legalized 1.1 mil- worries about the cost and availability ers returned. As a result, perishable lion unauthorized foreigners. of farm workers. crops, such as citrus, that were picked Unauthorized workers continued largely by labor contractor crews to arrive in the early 1990s and pre- included more unauthorized workers sented false documents to get hired, than lettuce crews that included work- that is, forged documents or documents ers hired directly by large growers. -

BY F7-6-4 AITORNEY Patented Jan

Jan. 15, 1935. G, VON ARCO 1,988,097 "FREQUENCY MULTIPLICATION Filed Dec. 10, 1929 w R S. a s n INVENTOR GEORG Wo ARCO BY f7-6-4 AITORNEY Patented Jan. 15, 1935 1988,097 UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE 1988,097 FREQUENCY MULTIPLICATION Georg von Arco, Berlin, Germany, assignor to Telefunken Geselschaft fir Drahtlose Tele graphie m. b. H., Berlin, Germany Application December 10, 1929, Serial No. 412,962 Renewed April 9, 1932 2 Claims. (C. 250-36) In my copending United States patent appli multiplier for use with my present invention cation Serial Number 70,729, fled November 23, although it is to be clearly understood that this 1925, now United States Patent 1,744,711, pat frequency multiplier or harmonic producer may ented January 21, 1930, I have disclosed an s efficient arrangement for frequency multiplying have wide application in the radio frequency or energy consisting of a master oscillator, means cognate arts rather than be limited to use in for splitting the phase of currents generated the System herein described. More specifically by the master oscillator and means for utilizing in connection with my harmonic oscillation gen the split phase currents to produce energy of erator, an object of my present invention is to O provide an electron discharge device having a multiplied frequency relative to the master OS parallel tuned circuit tuned to a harmonic fre 10 cillator frequency, by impulse excitation. In quency connected between its anode and cath that application, I referred to the efficient use of ode, and a Source of fundamental frequency en the System in directive transmitting arrange ergy connected or coupled to the control elec 5 ments, and this case which is a continuation in trode and cathode of the tube, the control elec part thereof, describes in detail how the ar trode or grid being so biased negatively that 5 rangement may be carried out. -

Aircraft Noise in Berlin Affects Quality of Life Even Outside the Airport Grounds

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Eibich, Peter; Kholodilin, Konstantin; Krekel, Christian; Wagner, Gert G. Article Aircraft noise in Berlin affects quality of life even outside the airport grounds DIW Economic Bulletin Provided in Cooperation with: German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) Suggested Citation: Eibich, Peter; Kholodilin, Konstantin; Krekel, Christian; Wagner, Gert G. (2015) : Aircraft noise in Berlin affects quality of life even outside the airport grounds, DIW Economic Bulletin, ISSN 2192-7219, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW), Berlin, Vol. 5, Iss. 9, pp. 127-133 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/107601 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu AIRCRAFT NOISE AND QUALITY OF LIFE Aircraft Noise in Berlin Affects Quality of Life Even Outside the Airport Grounds By Peter Eibich, Konstantin Kholodilin, Christian Krekel and Gert G. -

“More”? How Store Owners and Their Businesses Build Neighborhood

OFFERING “MORE”? HOW STORE OWNERS AND THEIR BUSINESSES BUILD NEIGHBORHOOD SOCIAL LIFE Vorgelegt von MA Soz.-Wiss. Anna Marie Steigemann Geboren in München, Deutschland von der Fakultät VI – Planen, Bauen, Umwelt der Technischen Universität Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktorin der Philosophie in Soziologie - Dr. phil - Genehmigte Dissertation Promotionsausschuss: Vorsitzende: Prof. Dr. Angela Million Gutachterin I: Prof. Dr. Sybille Frank Gutachter II: Prof. Dr. John Mollenkopf Gutachter III: Prof. Dr. Dietrich Henckel Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 10. August 2016 Berlin 2017 Author’s Declaration Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis and that this thesis and the work presented in it are my own and have been generated by me as the result of my own original research. In addition, I hereby confirm that the thesis at hand is my own written work and that I have used no other sources and aids other than those indicated. The author herewith confirms that she possesses the copyright rights to all parts of the scientific work, and that the publication will not violate the rights of third parties, in particular any copyright and personal rights of third parties. Where I have used thoughts from external sources, directly or indirectly, published or unpublished, this is always clearly attributed. All passages, which are quoted from publications, the empirical fieldwork, or paraphrased from these sources, are indicated as such, i.e. cited or attributed. The questionnaire and interview transcriptions are attached in the version that is not publicly accessible. This thesis was not submitted in the same or in a substantially similar version, not even partially, to another examination board and was not published elsewhere. -

Conceptions of Terror(Ism) and the “Other” During The

CONCEPTIONS OF TERROR(ISM) AND THE “OTHER” DURING THE EARLY YEARS OF THE RED ARMY FACTION by ALICE KATHERINE GATES B.A. University of Montana, 2007 B.S. University of Montana, 2007 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures 2012 This thesis entitled: Conceptions of Terror(ism) and the “Other” During the Early Years of the Red Army Faction written by Alice Katherine Gates has been approved for the Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures _____________________________________ Dr. Helmut Müller-Sievers _____________________________________ Dr. Patrick Greaney _____________________________________ Dr. Beverly Weber Date__________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Gates, Alice Katherine (M.A., Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures) Conceptions of Terror(ism) and the “Other” During the Early Years of the Red Army Faction Thesis directed by Professor Helmut Müller-Sievers Although terrorism has existed for centuries, it continues to be extremely difficult to establish a comprehensive, cohesive definition – it is a monumental task that scholars, governments, and international organizations have yet to achieve. Integral to this concept is the variable and highly subjective distinction made by various parties between “good” and “evil,” “right” and “wrong,” “us” and “them.” This thesis examines these concepts as they relate to the actions and manifestos of the Red Army Faction (die Rote Armee Fraktion) in 1970s Germany, and seeks to understand how its members became regarded as terrorists. -

Labour Migration from Indonesia

LABOUR MIGRATION FROM INDONESIA IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benets migrants and society. As an intergovernmental body, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and wellbeing of migrants. This publication is produced with the generous nancial support of the Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (United States Government). Opinions expressed in this report are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reect the views of IOM. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher: International Organization for Migration Mission in Indonesia LABOUR MIGRATION FROM INDONESIA Sampoerna Strategic Square, North Tower Floor 12A Jl. Jend. Sudirman Kav. 45-46 An Overview of Indonesian Migration to Selected Destinations in Asia and the Middle East Jakarta 12930 Indonesia © 2010 International Organization for Migration (IOM) IOM International Organization for Migration IOM International Organization for Migration Labour Migration from Indonesia TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii PREFACE ix EXECUTIVE SUMMARY xi ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS 1 INTRODUCTION 3 Purpose 3 Terminology 3 Methodology -

Kma 2 Kma 1 Interbau 7

WHO IS WHO? — WHO IS WHERE? LANDESDENKMALAMT 65 Dr. Christoph Rauhut 9 Landeskonservator und Leiter des Landesdenkmalamtes 1 Sabine Ambrosius, Referentin für Weltererbe – Altes Stadthaus, Klosterstraße 47, 10179 Berlin, 030 / 90259-3600 [email protected] 50 9 1 2 FRIEDRICHSHAIN 65 KMA 1 9 MIETERBEIRAT Karl-Marx-Allee vom Strausberger Platz 1 bis zur Proskauer und Niederbarnimstraße Vorsitzender: Norbert Bogedein, [email protected] – 61 STALINBAUTEN E.V. 1. Vorsitzender: Achim Bahr, 0160 / 91844921 9 1 [email protected], www.stalinbauten.de KMA UNTERE DENKMALSCHUTZBEHÖRDE FRIEDRICHSHAIN-KREUZBERG VON BERLIN, GEBIET FRIEDRICHSHAIN Till Peter Otto, 030 / 90298 8035, [email protected] FACHBEREICH STADTPLANUNG FRIEDRICHSHAIN-KREUZBERG VON BERLIN Leiter: Matthias Peckskamp, 030 / 90298 2234 [email protected] BEZIRKSSTADTRAT FÜR BAUEN, PLANEN UND FACILITY MANAGEMENT Florian Schmidt, 030 / 90298 3261, [email protected] INTERBAU 1957 – HANSAVIERTEL MITTE KRIEG ARCHITEKTUR UND KALTER BÜRGERVEREIN HANSAVIERTEL E.V. 1. Vorsitzende: Dr. Brigitta Voigt, [email protected], www.hansaviertel.berlin 7 5 UNTERE DENKMALSCHUTZBEHÖRDE MITTE VON BERLIN, ORTSTEILE MOABIT, 9 HANSAVIERTEL UND TIERGARTEN Leiter: Guido Schmitz, 030 / 9018 45887, [email protected] 1 FACHBEREICH STADTPLANUNG MITTE VON BERLIN 59 Leiterin: Kristina Laduch, [email protected] 9 1 STELLVERTRETENDER BEZIRKSBÜRGERMEISTER UND BEZIRKSSTADTRAT FÜR STADTENTWICKLUNG, – SOZIALES UND GESUNDHEIT 57 Ephraim Gothe, 030 / 9018 44600, [email protected] 9 1 INTERBAU 1957 – CORBUSIERHAUS CHARLOTTENBURG BERLIN FÖRDERVEREIN CORBUSIERHAUS BERLIN E.V. Vorsitzender: Marcus Nitschke, 030 / 89742310, [email protected] INTERBAU UNTERE DENKMALSCHUTZBEHÖRDE CHARLOTTENBURG-WILMERSDORF, ORTSTEIL WESTEND Herr Kümmritz, 030 / 9029 15127 [email protected] FACHBEREICH STADTPLANUNG Komm. -

1/5 Bezirksamt Mitte Von Berlin Datum

Bezirksamt Mitte von Berlin Datum: 30.12.2019 Stadtentwicklung, Soziales und Gesundheit Tel.: 44600 Bezirksamtsvorlage Nr. 998 zur Beschlussfassung - für die Sitzung am Dienstag, dem 07.01.2020 1. Gegenstand der Vorlage: Beschluss zur Festsetzung der Verordnung über die Erhaltung der städtebaulichen Eigenart aufgrund der städtebaulichen Gestalt für das Gebiet Hansaviertel im Bezirk Mitte von Berlin gemäß § 172 Abs. 1 Satz 1 Nr. 1 BauGB 2. Berichterstatter/in: Bezirksstadtrat Gothe 3. Beschlussentwurf: I. Das Bezirksamt beschließt: Die Verordnung über die Erhaltung der städtebaulichen Eigenart aufgrund der städtebaulichen Gestalt für das Gebiet Hansaviertel im Bezirk Mitte von Berlin gem. § 172 Abs. 1 Satz 1 Nr. 1 BauGB wird festgesetzt. Die Verordnung gilt für das in der anliegenden Karte (Anlage 2) im Maßstab 1:6.000 mit einer Linie eingegrenzte Gebiet. Die Karte ist Bestandteil dieser Verordnung. II. Eine Vorlage an die Bezirksverordnetenversammlung ist nicht erforderlich. III. Mit der Durchführung des Beschlusses wird die Abteilung Stadtentwicklung, Soziales und Gesundheit beauftragt. IV. Veröffentlichung: ja V. Beteiligung der Beschäftigtenvertretungen: nein a) Personalrat: b) Frauenvertretung: c) Schwerbehindertenvertretung: d) Jugend- und Auszubildendenvertretung: 4. Begründung: I. Rechtsverordnung (siehe Anlage) II. Plan mit Geltungsbereich (siehe Anlage) III. Begründung 1/5 1. Beschlussfassung politischer Gremien Das Bezirksamt Mitte von Berlin hat in seiner Sitzung am 20.12.2018 die Aufnahme des „Hansaviertels“ in die städtebauliche Förderkulisse (hier: Städtebaulicher Denkmalschutz) beschlossen (Drucksache Nr. 1614/V). Um ein geeignetes städtebauliches Instrument zum Erhalt des „Hansaviertels“ und damit zum Schutz vor baulichen Veränderungen des „Hansaviertels“ zu schaffen, soll eine Verordnung über die Erhaltung der städtebaulichen Eigenart auf Grund der städtebaulichen Gestalt für das Gebiet „Hansaviertel“ beschlossen werden.