The Effect of LGBT Film Exposure on Policy Preference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Daily Feather

Start Your Day with Danielle Macroeconomic Research Analysis & Insights Subscribe to The Daily Feather www.quillintelligence.com Deadpool of Labor VIPs Downward Payroll Revisions and • Powell’s characterization of the labor market being in “quite a strong Yield Curve Inversion Trending. position” defies Fed’s revision rule of thumb: three straight months Coincidence? We Think Not. of up or down revisions signal cycle turns; August marked month 120 Private Nonfarm Payroll Benchmark (avg per month, K) five, accompanied by a similar stretch of yield curve inversion Private Payroll Two-Month Revisions (sum total, K) 100 U.S. 3-month/10-year Yield Spread (bps) • Fed economists treat benchmark revisions as stronger indicators of 80 trend change vs. real time revisions with the first year of a significant benchmark revision tending to foreshadow the next; BLS private 60 payroll data was benchmark revised by -0.4%, the worst since 2010 40 • Analyzing the timeframe from January and March 2019 with the lat- 20 ter the last for which benchmark revisions are available indicates a 0 worsening trend suggesting next August’s BLS benchmark revision -20 through March 2020 will be deeper -40 -60 In Time travel has a protocol. But don’t let Deadpool 2 violating said -80 protocol, dictated by Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU —yes, there Apr MayJun JulAug SepOct NovDec Jan FebMar AprMay JunJul AugSep really is an acronym for that), dissuade you from catching the brilliant ‘18 ‘19 Source: Bloomberg, BLS, U.S. Treasury sequel to the quirkiest of all the mega-franchise’s offerings. So what if Cable, portrayed by Josh Brolin, changes the past in the present. -

Reflections from the Developments of School Science Curricula

Imitation game: Reflections from the developments of school science curricula SONG, Jinwoong (宋眞雄) Department of Physics Education, Seoul National University What will fulfill this need can be stated in equally simple terms. It is, ironically enough, that science be taught as science. (Joseph J. Schwab, 1962: 188-9) 1.Introduction The Imitation Game is a 2014 British historical drama film directed by Morten Tyldu m and written by Graham Moore, based on the biography Alan Turing: The Enigma by A ndrew Hodges. It stars Benedict Cumberbatch as British cryptanalyst Alan Turing, who dec rypted German intelligence codes for the British government during the Second World War (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Imitation_Game). The ’Imitation Game’ refers to so-calle d ‘Turing Test’ which is a test for artificial intelligence suggested by a famous British ma thematician, Alan Turing (1912-54), who is known as the father of the computer. Through his paper, “Computing machinery and intelligence” (1950), Tuning gave a conceptual fou ndation of AI (Artificial Intelligence), by suggesting the Turing Test, “a test of a machine’ s ability to exhibit intelligent behavior equivalent to, or indistinguishable from, that of a h uman.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turing_test) Science is now considered as one of the core (often three of them) subjects across th e world, together with the national language and mathematics. For example, in PISA studi es, science is included in the three main areas, with literacy and mathematics (e.g. OECD, 2018). And, in TIMSS studies, science and mathematics are the two main subjects for th e international comparison (https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2015/). -

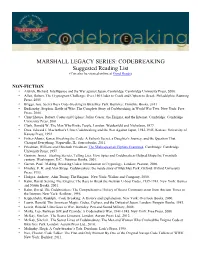

CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can Also Be Viewed Online at Good Reads)

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can also be viewed online at Good Reads) NON-FICTION • Aldrich, Richard. Intelligence and the War against Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. • Allen, Robert. The Cryptogram Challenge: Over 150 Codes to Crack and Ciphers to Break. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2005 • Briggs, Asa. Secret Days Code-breaking in Bletchley Park. Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2011 • Budiansky, Stephen. Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War Two. New York: Free Press, 2000. • Churchhouse, Robert. Codes and Ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. • Clark, Ronald W. The Man Who Broke Purple. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1977. • Drea, Edward J. MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942-1945. Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1992. • Fisher-Alaniz, Karen. Breaking the Code: A Father's Secret, a Daughter's Journey, and the Question That Changed Everything. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2011. • Friedman, William and Elizebeth Friedman. The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957. • Gannon, James. Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth century. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2001. • Garrett, Paul. Making, Breaking Codes: Introduction to Cryptology. London: Pearson, 2000. • Hinsley, F. H. and Alan Stripp. Codebreakers: the inside story of Bletchley Park. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. • Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma. New York: Walker and Company, 2000. • Kahn, David. Seizing The Enigma: The Race to Break the German U-boat Codes, 1939-1943. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2001. • Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. -

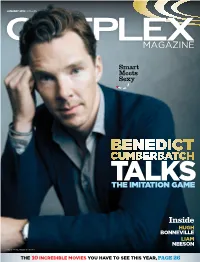

Benedict Cumberbatch Talks the Imitation Game

JANUARY 2015 | VOLUME 16 | NUMBER 1 Smart Meets Sexy BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH TALKS THE IMITATION GAME Inside HUGH BONNEVILLE LIAM NEESON PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 41619533 THE 10 INCREDIBLE MOVIES YOU HAVE TO SEE THIS YEAR, PAGE 26 CONTENTS JANUARY 2015 | VOL 16 | Nº1 COVER STORY 40 GENIUS ROLE Benedict Cumberbatch’s fervent fans won’t be disappointed with his latest role. The Imitation Game casts the 38-year-old Brit as Alan Turing, a gay, mathematical genius who helped hasten the end of WWII. Here he talks about bringing Turing to life and his various other talents BY INGRID RANDOJA REGULARS 4 EDITOR’S NOTE 8 SNAPS 10 IN BRIEF 14 SPOTLIGHT: CANADA 16 ALL DRESSED UP 20 IN THEATRES 44 CASTING CALL 47 RETURN ENGAGEMENT 48 AT HOME 50 FINALLY… FEATURES IMAGE HARGRAVE/AUGUST AUSTIN BY PHOTO COVER 26 2015’S BIG PICS! 32 FABLED CAST 34 MAN OF ACTION 38 PAPA BEAR It’s going to be an epic year We break down which famous Taken 3 star Liam Neeson Paddington’s Hugh Bonneville at the movies. We take you actors play which well-known talks about his longtime says playing father figure to a through the 10 films you must fairy tale characters in love of action movies, and mischievous talking bear gave see, starting with the return of the musical extravaganza recent decision to get clean him the chance to revisit his Star Wars! Into the Woods and healthy own childhood BY INGRID RANDOJA BY INGRID RANDOJA BY BOB STRAUSS BY INGRID RANDOJA JANUARY 2015 | CINEPLEX MAGAZINE | 3 EDITOR’S NOTE PUBLISHER SALAH BACHIR EDITOR MARNI WEISZ DEPUTY EDITOR INGRID RANDOJA ART DIRECTOR TREVOR THOMAS STEWART ASSISTANT ART DIRECTOR STEVIE SHIPMAN VICE PRESIDENT, PRODUCTION SHEILA GREGORY CONTRIBUTORS LEO ALEFOUNDER, BOB STRAUSS ADVERTISING SALES FOR CINEPLEX MAGAZINE AND LE MAGAZINE CINEPLEX IS HANDLED BY CINEPLEX MEDIA. -

Videos, Podcasts, TV, Film, Music, Song

APA Referencing 7th edition – References format (7): Videos, Podcasts, TV, Film, Music, Song Publication Formatting instructions Template – Reference Format Type YouTube or Family name of person or name of Hayashi, Y. [Toast It Up]. (2020, February 10. Answering to "How can I become fluent in a video from group that uploaded the video. Then foreign language?" [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/AFnyQnCcJio other online username in title caps in brackets. Then sources or year of publication, month and date in [Source: Video from YouTube social media site] social media parenthesis. Then title of video in letter OR caps and italics with description in brackets. Then name of streaming Cookie Studio. (2019, July 3). Amazon – Making of [Video]. Vimeo. service in title caps. Then URL https://vimeo.com/345947153 Omit the username if it is the same as the author’s or group name [Source: Video from other online social media] Podcast or Family name of executive producer or Hasan. M. (Podcast Host). (2018-present). Deconstructed with Mehdi Hasan [Audio podcast]. single episode host of podcast. Then description in The Intercept. https://theintercept.com/podcasts/deconstructed/ in a podcast parenthesis. Then range of years in series publication in parenthesis. The title of [Source: Podcast from other online podcast website with transcripts] podcast in letter caps and italics with OR description in brackets. Then name of production company. Then URL Reber, S. (Executive Producer). (2020, March 9). The reporters (No. 4) [Audio podcast If single episode, write year, month and episode]. In Verified. Scripps Washington Bureau. https://www.radio.com/media/audio- date of broadcast in parenthesis instead of range of years. -

January 2020 the Lighthouse Robert Eggers the Irish Film Institute

JANUARY 2020 THE LIGHTHOUSE ROBERT EGGERS THE IRISH FILM INSTITUTE The Irish Film Institute is Ireland’s EXHIBIT national cultural institution for film. It aims to exhibit the finest in independent, Irish and international cinema, preserve PRESERVE Ireland’s moving image heritage at the Irish Film Archive, and encourage EDUCATE engagement with film through its various educational programmes. THE NIGHT WINTER MENU OF IDEAS 2020 Fancy some healthy and hearty food this January? Look The Night of Ideas is a worldwide initiative, spearheaded by no further than the IFI Café Bar’s delicious winter menu, Institut Français, that celebrates the constant stream of ideas featuring new dishes including Wicklow Lamb Stew, between countries, cultures, and generations. The IFI and Vegetarian Lasagne, and Warm Winter Veg with Harissa the French Embassy are proud to present this third edition in Yoghurt and Beetroot Crisps. Book your table by emailing Ireland, the theme of which is ‘Being Alive’. For more details on [email protected] or by ringing 01-6798712. the event, please see page 15. NAME YOUR SEAT COMING SOON Parasite Naming a seat in the newly refurbished Cinema 1 is a Coming to the IFI in February are two of the year’s most fantastic way to demonstrate your own passion for film, anticipated new releases: Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite, winner of celebrate the memory of someone who loved the IFI, or the 2019 Palme d’Or and hotly tipped for Oscar glory, follows the gift a unique birthday or anniversary present to the film sinister relationship between an unemployed family and their fan in your life! The only limit is 50 characters and your patrons; and Céline Sciamma’s stunning Portrait of a Lady on Fire, imagination. -

Why Python for Chatbots

Schedule: 1. History of chatbots and Artificial Intelligence 2. The growing role of Chatbots in 2020 3. A hands on look at the A.I Chatbot learning sequence 4. Q & A Session Schedule: 1. History of chatbots and Artificial Intelligence 2. The growing role of Chatbots in 2020 3. A hands on look at the A.I Chatbot learning sequence 4. Q & A Session Image credit: Archivio GBB/Contrasto/Redux History •1940 – The Bombe •1948 – Turing Machine •1950 – Touring Test •1980 Zork •1990 – Loebner Prize Conversational Bots •Today – Siri, Alexa Google Assistant Image credit: Photo 172987631 © Pop Nukoonrat - Dreamstime.com 1940 Modern computer history begins with Language Analysis: “The Bombe” Breaking the code of the German Enigma Machine ENIGMA MACHINE THE BOMBE Enigma Machine image: Photographer: Timothy A. Clary/AFP The Bombe image: from movie set for The Imitation Game, The Weinstein Company 1948 – Alan Turing comes up with the concept of Turing Machine Image CC-BY-SA: Wikipedia, wvbailey 1948 – Alan Turing comes up with the concept of Turing Machine youtube.com/watch?v=dNRDvLACg5Q 1950 Imitation Game Image credit: Archivio GBB/Contrasto/Redux Zork 1980 Zork 1980 Text parsing Loebner Prize: Turing Test Competition bit.ly/loebnerP Conversational Chatbots you can try with your students bit.ly/MITsuku bit.ly/CLVbot What modern chatbots do •Convert speech to text •Categorise user input into categories they know •Analyse the emotion emotion in user input •Select from a range of available responses •Synthesize human language responses Image sources: Biglytics -

When Deadpool 2 (

Sign in (https://www.gamespot.com/) (https://www.gamespot.com/login/) / Join (https://www.gamespot.com/signup/) (https://www.facebook.com/sharer/sharer.php? u=https://www.gamespot.com/gallery/deadpool- 2-super-duper-extended-vs-theatrical-cut- /2900-2191/) (https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?text=Deadpool 2 Super Duper Extended Vs. Theatrical Cut -- Every Change&related=&url=https://www.gamespot.com/gallery/deadpool- 2-super-duper-extended-vs-theatrical-cut-/2900-2191/) (https://share.flipboard.com/bookmarklet/popout? v=2&title=Deadpool 2 Super Duper Extended Vs. Theatrical Cut -- Every Change&url=https://www.gamespot.com/gallery/deadpool- 2-super-duper-extended-vs-theatrical-cut-/2900- 2191/&utm_source=gamespot.com&utm_medium=article- share&utm_campaign=publisher) Spider-Man Far From Home Trailer Breakdown And Easter Eggs True Detective Season 3 Theories From Episodes 1 and 2 Game Of Thrones Season 8 Release Date Trailer Breakdown (https://static.gamespot.com/uploads/scale_super/1578/15789737/3424064-deadpool2.jpg) When Deadpool 2 (https://www.gamespot.com/articles/deadpool-2-review-failing-to-break-the-fourth- wall/1100-6458947/) hit theaters, you might have assumed it would be impossible to somehow load in more dirty jokes or gratuitous violence. How wrong you were, though. While the film is certainly raunchy, perhaps even more so than the first Deadpool, there's always room for more. That's proven by the Super Duper cut of the movie, which has been released on Digital HD. This version of Deadpool 2 first debuted at San Diego Comic-Con and will arrive on Blu-ray (https://www.gamespot.com/articles/this-deadpool-2-blu-ray-comes-with-a-very-special-/1100- 6460283/) on August 21. -

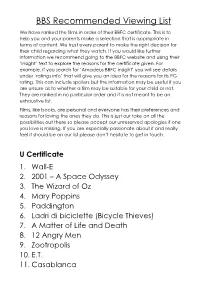

BBS Recommended Viewing List

BBS Recommended Viewing List We have ranked the films in order of their BBFC certificate. This is to help you and your parents make a selection that is appropriate in terms of content. We trust every parent to make the right decision for their child regarding what they watch. If you would like further information we recommend going to the BBFC website and using their ‘Insight’ text to explore the reasons for the certificate given. For example, if you search for ‘Amadeus BBFC insight’ you will see details under ‘ratings info’ that will give you an idea for the reasons for its PG rating. This can include spoilers but the information may be useful if you are unsure as to whether a film may be suitable for your child or not. They are ranked in no particular order and it is not meant to be an exhaustive list. Films, like books, are personal and everyone has their preferences and reasons for loving the ones they do. This is just our take on all the possibilities out there so please accept our unreserved apologies if one you love is missing. If you are especially passionate about it and really feel it should be on our list please don’t hesitate to get in touch. U Certificate 1. Wall-E 2. 2001 – A Space Odyssey 3. The Wizard of Oz 4. Mary Poppins 5. Paddington 6. Ladri di biciclette (Bicycle Thieves) 7. A Matter of Life and Death 8. 12 Angry Men 9. Zootropolis 10. E.T. 11. Casablanca 12. Sense and Sensibility 13. -

Order Form Full

JAZZ ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL ADDERLEY, CANNONBALL SOMETHIN' ELSE BLUE NOTE RM112.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS LOUIS ARMSTRONG PLAYS W.C. HANDY PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS & DUKE ELLINGTON THE GREAT REUNION (180 GR) PARLOPHONE RM124.00 AYLER, ALBERT LIVE IN FRANCE JULY 25, 1970 B13 RM136.00 BAKER, CHET DAYBREAK (180 GR) STEEPLECHASE RM139.00 BAKER, CHET IT COULD HAPPEN TO YOU RIVERSIDE RM119.00 BAKER, CHET SINGS & STRINGS VINYL PASSION RM146.00 BAKER, CHET THE LYRICAL TRUMPET OF CHET JAZZ WAX RM134.00 BAKER, CHET WITH STRINGS (180 GR) MUSIC ON VINYL RM155.00 BERRY, OVERTON T.O.B.E. + LIVE AT THE DOUBLET LIGHT 1/T ATTIC RM124.00 BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY (PURPLE VINYL) LONESTAR RECORDS RM115.00 BLAKEY, ART 3 BLIND MICE UNITED ARTISTS RM95.00 BROETZMANN, PETER FULL BLAST JAZZWERKSTATT RM95.00 BRUBECK, DAVE THE ESSENTIAL DAVE BRUBECK COLUMBIA RM146.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - OCTET DAVE BRUBECK OCTET FANTASY RM119.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - QUARTET BRUBECK TIME DOXY RM125.00 BRUUT! MAD PACK (180 GR WHITE) MUSIC ON VINYL RM149.00 BUCKSHOT LEFONQUE MUSIC EVOLUTION MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY MIDNIGHT BLUE (MONO) (200 GR) CLASSIC RECORDS RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY WEAVER OF DREAMS (180 GR) WAX TIME RM138.00 BYRD, DONALD BLACK BYRD BLUE NOTE RM112.00 CHERRY, DON MU (FIRST PART) (180 GR) BYG ACTUEL RM95.00 CLAYTON, BUCK HOW HI THE FI PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 COLE, NAT KING PENTHOUSE SERENADE PURE PLEASURE RM157.00 COLEMAN, ORNETTE AT THE TOWN HALL, DECEMBER 1962 WAX LOVE RM107.00 COLTRANE, ALICE JOURNEY IN SATCHIDANANDA (180 GR) IMPULSE -

Pasdecrisepourles Locauxd'entreprises

Big Caesar Chicken Salad Auch als Chicken McWrap® Chicken Caesar Ab 03.02.2020 /mcdlu 4Käsegipfel Riffelkartoffeln As long as stocks last. ©2020McDonald’s Coca-Cola ist eineeingetragene Schutzmarkeder TheCoca-ColaCompany. N°2832 MERCREDI Pas de crise pour les 29 JANVIER 2020 Europe 9 Le Portugal ne sera plus un eldorado pour les retraités locaux d'entreprises Le dynamisme sur le marché de l'immobi- cinq ans. Même constat pour les surfaces lier d'entreprise au Grand-Duché ne se dé- commerciales, portées par des projets tels ment pas. Selon des chiffres présentés hier le centre commercial Cloche d'Or ou le com- par JLL, la prise en occupation des bureaux plexe Royal-Hamilius. Là, la prise en occu- en 2019 a dépassé de 20 % la moyenne sur pation s'est carrément envolée. PAGE 12 Ruée sur les masques au Luxembourg Cinéma 15-26 Avant «#MeToo», scandale à la télévision américaine Sports 39 Danel Sinani attendra l'été pour rejoindre l'Angleterre Météo 40 La demande en masques de protection a largement augmenté au Luxembourg. Certaines pharmacies sont en rupture de stock. MATIN APRÈS-MIDI LUXEMBOURG Après des cas signalés 100 morts en Chine et ne cesse de cies ont été prises d'assaut pour en France et en Allemagne, la progresser, à tel point que le des demandes de masques de pro- 2° 5° crainte du coronavirus gagne le Grand-Duché a relevé son niveau tection. Des établissements sont Luxembourg. Ce virus a fait plus de d'alerte. Conséquence, les pharma- déjà en rupture de stock. PAGE 3 2 Actu MERCREDI 29 JANVIER 2020 / LESSENTIEL.LU «Igor le Russe» en box blindé Un espoir du cinéma français arrêté MADRID L'Espagne juge depuis MARSEILLE Révélé par hier dans un box blindé un son rôle dans le film «Shé- meurtrier présumé surnommé hérazade», Dylan Robert, «Igor le Russe», condamné 20 ans, dort en prison. -

FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 56 Days That Will Rock Your Cinema World!

10 JAN 20 5 MAR 20 1 | 10 JAN 20 - 5 MAR 20 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSECINEMA.COM FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 56 days that will rock your cinema world! Well, here we are again… it’s Awards season! I was reminded of such by a communication that came my way from AMPAS (the Oscar® people) listing nine categories’ shortlists of potential nominees. Now, they’ve been doing that shortlist thing with Foreign Language films for quite some time – there’s a lot of films out there in the world, it would be rather too much for the Academy members to have to watch them all! – but, to my knowledge, they’ve not before done it with any other category. It may be it’s for the same reason of sheer volume as above, but I guess what it also does is allows a greater number of films a reason to mention their Academy Award status in their advertising. I can see it now, “Academy Award Nomination shortlisted…” written on the poster. Where will it all end I wonder, “Academy Award Nomination eligible…”? As luck would have [nothing to do with] it, one of the films on the Foreign Language short list – which at this point in time seems the overwhelming favourite – is Bong Joon Ho’s utterly brilliant Parasite, which takes its place alongside a programme of films that is simplythe best line-up of new cinema I’ve seen in a long time. There’s not just the aforementioned South Korean masterpiece, there’s Sam Mendes’ extraordinary ‘one-take’ wonder 1917 (google ‘1917 behind the scenes featurette’ and prepare to simply have to see this film); Taika (‘Wilderpeople’) Waititi’s WWII, Nazi Germany-set, Jojo Rabbit; Armando Iannucci’s breathless Dickens, The Personal History of David Copperfield; Robert Egger’s uniquely bonkers, fog-bound The Lighthouse; Kidman, Robbie and Theron taking on the Fox News patriarchy in Bombshell; and to cap it all off, and possibly the best of the lot, Céline Sciamma’sexquisite Portrait of a Lady on Fire.