In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

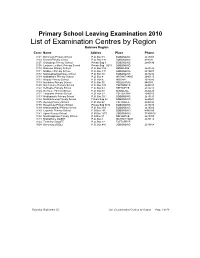

List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O

Primary School Leaving Examination 2010 List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O. Box 48 BOBONONG 2619207 0103 Borotsi Primary School P.O. Box 136 BOBONONG 819208 0107 Gobojango Primary School Private Bag 8 BOBONONG 2645436 0108 Lentswe-Le-Moriti Primary School Private Bag 0019 BOBONONG 0110 Mabolwe Primary School P.O. Box 182 SEMOLALE 2645422 0111 Madikwe Primary School P.O. Box 131 BOBONONG 2619221 0112 Mafetsakgang primary school P.O. Box 46 BOBONONG 2619232 0114 Mathathane Primary School P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0117 Mogapi Primary School P.O. Box 6 MOGAPI 2618545 0119 Molalatau Primary School P.O. Box 50 MOLALATAU 845374 0120 Moletemane Primary School P.O. Box 176 TSETSEBYE 2646035 0123 Sefhophe Primary School P.O. Box 41 SEFHOPHE 2618210 0124 Semolale Primary School P.O. Box 10 SEMOLALE 2645422 0131 Tsetsejwe Primary School P.O. Box 33 TSETSEJWE 2646103 0133 Modisaotsile Primary School P.O. Box 591 BOBONONG 2619123 0134 Motlhabaneng Primary School Private Bag 20 BOBONONG 2645541 0135 Busang Primary School P.O. Box 47 TSETSEBJE 2646144 0138 Rasetimela Primary School Private Bag 0014 BOBONONG 2619485 0139 Mabumahibidu Primary School P.O. Box 168 BOBONONG 2619040 0140 Lepokole Primary School P O Box 148 BOBONONG 4900035 0141 Agosi Primary School P O Box 1673 BOBONONG 71868614 0142 Motsholapheko Primary School P O Box 37 SEFHOPHE 2618305 0143 Mathathane DOSET P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0144 Tsetsebye DOSET P.O. Box 33 TSETSEBYE 3024 Bobonong DOSET P.O. Box 483 BOBONONG 2619164 Saturday, September 25, List of Examination Centres by Region Page 1 of 39 Boteti Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0201 Adult Education Private Bag 1 ORAPA 0202 Baipidi Primary School P.O. -

Botswana Semiology Research Centre Project Seismic Stations In

BOTSWANA SEISMOLOGICAL NETWORK ( BSN) STATIONS 19°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 21°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 1 S 7 " ° 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° " 7 S 1 KSANE Kasane ! !Kazungula Kasane Forest ReserveLeshomo 1 S Ngoma Bridge ! 8 " ! ° 0 0 ' # !Mabele * . MasuzweSatau ! ! ' 0 ! ! Litaba 0 ° Liamb!ezi Xamshiko Musukub!ili Ivuvwe " 8 ! ! ! !Seriba Kasane Forest Reserve Extension S 1 !Shishikola Siabisso ! ! Ka!taba Safari Camp ! Kachikau ! ! ! ! ! ! Chobe Forest Reserve ! !! ! Karee ! ! ! ! ! Safari Camp Dibejam!a ! ! !! ! ! ! ! X!!AUD! M Kazuma Forest Reserve ! ShongoshongoDugamchaRwelyeHau!xa Marunga Xhauga Safari Camp ! !SLIND Chobe National Park ! Kudixama Diniva Xumoxu Xanekwa Savute ! Mah!orameno! ! ! ! Safari Camp ! Maikaelelo Foreset Reserve Do!betsha ! ! Dibebe Tjiponga Ncamaser!e Hamandozi ! Quecha ! Duma BTLPN ! #Kwiima XanekobaSepupa Khw!a CHOBE DISTRICT *! !! ! Manga !! Mampi ! ! ! Kangara # ! * Gunitsuga!Njova Wazemi ! ! G!unitsuga ! Wazemi !Seronga! !Kaborothoa ! 1 S Sibuyu Forest Reserve 9 " Njou # ° 0 * ! 0 ' !Nxaunxau Esha 12 ' 0 Zara ! ! 0 ° ! ! ! " 9 ! S 1 ! Mababe Quru!be ! ! Esha 1GMARE Xorotsaa ! Gumare ! ! Thale CheracherahaQNGWA ! ! GcangwaKaruwe Danega ! ! Gqose ! DobeQabi *# ! ! ! ! Bate !Mahito Qubi !Mahopa ! Nokaneng # ! Mochabana Shukumukwa * ! ! Nxabe NGAMILAND DISTRICT Sorob!e ! XurueeHabu Sakapane Nxai National Nark !! ! Sepako Caecae 2 ! ! S 0 " Konde Ncwima ° 0 ! MAUN 0 ' ! ! ' 0 Ntabi Tshokatshaa ! 0 ° ! " 0 PHDHD Maposa Mmanxotai S Kaore ! ! Maitengwe 2 ! Tsau Segoro -

Kgatleng SUB District

Kgatleng SUB District VOL 5.0 KGATLENG SUB DISTRICT Population and Housing Census 2011 Selected Indicators for Villages and Localities ii i Population and Housing Census 2011 [ Selected indicators ] Kgatleng Sub District Population and Housing Census 2011 [Selected Indicators] Kgatleng Sub District 3 Table of Contents Kgatleng Sub District Population And Housing Census 2011: Selected Indicators For Villages And Localities Preface 3 VOL 5,0 1.0 Background and Commentary 6 1.1 Background to the Report 6 Published by 1.2 Importance of the Report 6 STATISTICS BOTSWANA Private Bag 0024, Gaborone 2.0 Population Distribution 6 Phone: (267)3671300, 3.0 Population Age Structure 6 Fax: (267) 3952201 Email: [email protected] 3.1 The Youth 7 Website: www.cso.gov.bw/cso 3.2 The Elderly 7 4.0 Annual Growth Rate 7 5.0 Household Size 7 COPYRIGHT RESERVED 6.0 Marital Status 8 7.0 Religion 8 Extracts may be published if source is duly acknowledged 8.0 Disability 9 9.0 Employment and Unemployment 9 10.0 Literacy 10 ISBN: 978-99968-429-7-9 11.0 Orphan-hood 10 12.0 Access to Drinking Water and Sanitation 10 12.1 Access to Portable Water 10 12.2 Access to Sanitation 11 13.0 Energy 11 13.1 Source of Fuel for Heating 11 13.2 Source of Fuel for Lighting 12 13.3 Source of Fuel for Cooking 12 14.0 Projected Population 2011 – 2026 13 Annexes 14 iii Population and Housing Census 2011 [ Selected indicators ] Kgatleng Sub District Population and Housing Census 2011 [Selected Indicators] Kgatleng Sub District 1 FIGURE 1: MAP OF KATLENG DISTRICT Preface This report follows our strategic resolve to disaggregate the 2011 Population and Housing Census report, and many of our statistical outputs, to cater for specific data needs of users. -

2011 Population & Housing Census Preliminary Results Brief

2011 Population & Housing Census Preliminary Results Brief For further details contact Census Office, Private Bag 0024 Gaborone: Tel 3188500; Fax 3188610 1. Botswana Population at 2 Million Botswana’s population has reached the 2 million mark. Preliminary results show that there were 2 038 228 persons enumerated in Botswana during the 2011 Population and Housing Census, compared with 1 680 863 enumerated in 2001. Suffice to note that this is the de-facto population – persons enumerated where they were found during enumeration. 2. General Comments on the Results 2.1 Population Growth The annual population growth rate 1 between 2001 and 2011 is 1.9 percent. This gives further evidence to the effect that Botswana’s population continues to increase at diminishing growth rates. Suffice to note that inter-census annual population growth rates for decennial censuses held from 1971 to 2001 were 4.6, 3.5 and 2.4 percent respectively. A close analysis of the results shows that it has taken 28 years for Botswana’s population to increase by one million. At the current rate and furthermore, with the current conditions 2 prevailing, it would take 23 years for the population to increase by another million - to reach 3 million. Marked differences are visible in district population annual growths, with estimated zero 3 growth for Selebi-Phikwe and Lobatse and a rate of over 4 percent per annum for South East District. Most district growth rates hover around 2 percent per annum. High growth rates in Kweneng and South East Districts have been observed, due largely to very high growth rates of villages within the proximity of Gaborone. -

E-Government and Democracy in Botswana: Observational and Experimental Evidence on the Effects of E-Government Usage on Political Attitudes

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bante, Jana et al. Working Paper E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021 Provided in Cooperation with: German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn Suggested Citation: Bante, Jana et al. (2021) : E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes, Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021, ISBN 978-3-96021-153-2, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn, http://dx.doi.org/10.23661/dp16.2021 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/234177 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

A Report on Attitudes Towards Family Planning & Family Size in Botswana

~'2 A Report on Attitudes towards Family Planning & Family Size in Botswana By Pia du Pradal March 1983 PREFACE The following is a report on a -survey which investigated the atti tudes of Batswana men, women and youths to family planning and family size. The research was conducted between September 1981 and May 1982 by the students of the Department of Nursing Education, University of Botswana in conjunction with the Department of Maternal/Child Health and Family Planning, Ministry of Health. The project was funded by the Research Triangle Institute in North Carolina (Sub-Contract No 9-214-1920) and further supported by US AID, Botswana which funded the services of the co-ordinator. I would like to express my sincere thanks to the many people who assisted with this project. Particular mention should be made of Karen B Allen, Dr Ellen Fried and Dr Dennis Chao of RTI who supported the project during its implementation and provided invaluable assis tance in the data analysis; Dr Mashalaba of the Department of MCH & FP whose sincere interest in the project stimulated it throughout; Mrs Kupe of the Department of Nursing Education who provided the full support of her faculty; and Mr C Gordon of US AID without whose encouragement the project would never have been implemented. I would also like to thank those students who participated in the project working long hours during weekends and holidays in order to keep the project on schedule and to rectify errors. Finally, I would like to thank Chief Linchwe II for allowing us to conduct this research amongst the Bakgatla and the 826 respondents who answered the questions so explicitly. -

Establishment of Subordinate Land Boards (Amendment) Order

CHAPTER 32:02 - TRIBAL LAND: SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION INDEX TO SUBSIDIARY LEGISLATION Establishment of Subordinate Land Boards (Amendment) Order Establishment of Subordinate Land Boards Order Tribal Land (Establishment of Land Tribunals) Order Tribal Land (Subordinate Land Boards) Regulations Tribal Land Regulations ESTABLISHMENT OF SUBORDINATE LAND BOARDS ORDER (under section 19) (15th June, 1973) ARRANGEMENT OF PARAGRAPHS PARAGRAPH 1. Citation 2. Establishment 3. Area of jurisdiction 4. Functions Schedule S.I. 47, 1973, S.I. 3, 1979, S.I. 125, 1979, S.I. 132, 1980, S.I. 78, 1981, S.I. 81, 1981, S.I. 110, 1981, S.I. 68, 1982, S.I. 5, 1984, S.I. 92, 1984, S.I. 36, 1986, S.I. 55,1987, S.I. 97, 1989, S.I. 45, 1992, S.I. 66, 1994, S.I. 53, 2002. 1. Citation Copyright Government of Botswana This Order may be cited as the Establishment of Subordinate Land Boards Order. 2. Establishment The subordinate land boards referred to in the second column of the Schedule hereto are established as the subordinate land boards within the district named in the first column of the said Schedule. 3. Area of jurisdiction The area of jurisdiction in respect of which each subordinate Land Board will perform its functions shall be the area or villages stated in relation to each subordinate land board in the third column of the Schedule. 4. Functions (1) The functions under customary law which vest in the subordinate land authority which are transferred to the subordinate land board shall include the hearing, grant or refusal of applications to use land for— ( a) building residences or extensions thereto; ( b) ploughing to a maximum extent of land determined by the tribal land board; ( c) grazing cattle or other stock; ( d) communal uses in the village. -

Prof Makgala Book Text Vol 47 2.Indd

Botswana Notes and Records, Volume 47 The Correspondence Between Isaac Schapera in London and Sandy Grant in Mochudi, 1968- 1985 Edited with Explanatory Notes by Sandy Grant Up to 1979, the two correspondents, Isaac Schapera1 the master academic and the non-academic Sandy Grant2 addressed each other formally. Thereafter, the relationship warmed. Helping to bring the two closer together was their shared friendship with Amos Pilane, in particular, who had previously been one of Schapera’s informants. Grant describes Amos’ last days, and reports the deaths of Lesaane and Francis Phirie. Schapera reacts. The correspondence has rare value in providing additional information about bogwera as it had been re-instituted by Kgosi Linchwe II, records Schapera’s reaction to the visit he made with Kgosi Linchwe to the initiates camp, provides detail about the re-publication by the Phuthadikobo Museum of Schapera’s out of print ‘History of the Bakgatla’ and his Bogwera. The correspondence is also on Schapera’s fi rst post-Independence visit to Mochudi, his award of an honorary degree by the University of Botswana as well as providing his important recollections about artefacts of major importance, Kgosi Lentswe I’s rain making equipment and the copper/brass necklet, the mfi tshana. There appears to be no obvious explanation for the termination of the correspondence. Figureg 1: Amos Pilane (photographed(pp g p byy Sandyy Grant)) Schapera (from the London School of Economics) to Grant, 1 November 1968 (Responding to an initial letter from Grant says], ‘I am not sure from your letter if you wish to do serious historical research, write a popular book on Tswana history for the general public or compile a reader for use in Tswana schools.. -

List of Cities in Botswana

List of cities in Botswana The following is a list of cities and towns in Botswana with population of over 3,000 citizens. State capitals are shown in boldface. Population Female Rank Name District Census District [1] Male Population 2001. Population 1. Gaborone South-East District Gaborone 186,007 91,823 94,184 2. Francistown North-East District Francistown 83,023 40,134 42,889 3. Molepolole Kweneng District Kweneng East 62,739 28,617 34,122 4. Serowe Central District Central Serowe/Palapye 52,831 25,400 27,431 5. Selibe Phikwe Central District Selibe Phikwe 49,849 24,334 25,515 6. Maun North-West District Ngamiland East 49,822 23,714 26,108 7. Kanye Southern District Ngwaketse 48,143 22,451 25,692 8. Mahalapye Central District Central Mahalapye 43,538 21,120 22,418 9. Mogoditshane Kweneng District Kweneng East 40,753 20,972 19,781 10. Mochudi Kgatleng District Kgatleng 39,349 18,490 20,859 11. Lobatse South-East District Lobatse 29,689 14,202 15,487 12. Palapye Central District Central Serowe/Palapye 29,565 13,995 15,570 13. Ramotswa South-East District South East 25,738 12,027 13,711 14. Moshupa Southern District Ngwaketse 22,811 10,677 12,134 15. Tlokweng South-East District South East 22,038 10,568 11,470 16. Bobonong Central District Central Bobonong 21,020 9,877 11,143 17. Thamaga Kweneng District Kweneng East 20,527 9,332 11,195 18. Letlhakane Central District Central Boteti 19,539 9,848 9,691 19. -

BOTSWANA ENVIRONMENT STATISTICS 2016 Revised Version (RV)

BOTSWANA ENVIRONMENT STATISTICS 2016 Revised Version (RV) ----- ------- --- ---- --- -- ------ -------- -- -- -- --- - -- --- -- -- - - -- - -- -- - -- - - - - - - -- - - -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- -- -- - - - - - - -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - --- - --- - -- --- - - - - -- - - - - - - -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -- ---- - - - -- - - -- -- - - - - - - -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - --- ----- - - - - - - - -- -- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Public Primary Schools

PRIMARY SCHOOLS CENTRAL REGION NO SCHOOL ADDRESS LOCATION TELE PHONE REGION 1 Agosi Box 378 Bobonong 2619596 Central 2 Baipidi Box 315 Maun Makalamabedi 6868016 Central 3 Bobonong Box 48 Bobonong 2619207 Central 4 Boipuso Box 124 Palapye 4620280 Central 5 Boitshoko Bag 002B Selibe Phikwe 2600345 Central 6 Boitumelo Bag 11286 Selibe Phikwe 2600004 Central 7 Bonwapitse Box 912 Mahalapye Bonwapitse 4740037 Central 8 Borakanelo Box 168 Maunatlala 4917344 Central 9 Borolong Box 10014 Tatitown Borolong 2410060 Central 10 Borotsi Box 136 Bobonong 2619208 Central 11 Boswelakgomo Bag 0058 Selibe Phikwe 2600346 Central 12 Botshabelo Bag 001B Selibe Phikwe 2600003 Central 13 Busang I Memorial Box 47 Tsetsebye 2616144 Central 14 Chadibe Box 7 Sefhare 4640224 Central 15 Chakaloba Bag 23 Palapye 4928405 Central 16 Changate Box 77 Nkange Changate Central 17 Dagwi Box 30 Maitengwe Dagwi Central 18 Diloro Box 144 Maokatumo Diloro 4958438 Central 19 Dimajwe Box 30M Dimajwe Central 20 Dinokwane Bag RS 3 Serowe 4631473 Central 21 Dovedale Bag 5 Mahalapye Dovedale Central 22 Dukwi Box 473 Francistown Dukwi 2981258 Central 23 Etsile Majashango Box 170 Rakops Tsienyane 2975155 Central 24 Flowertown Box 14 Mahalapye 4611234 Central 25 Foley Itireleng Box 161 Tonota Foley Central 26 Frederick Maherero Box 269 Mahalapye 4610438 Central 27 Gasebalwe Box 79 Gweta 6212385 Central 28 Gobojango Box 15 Kobojango 2645346 Central 29 Gojwane Box 11 Serule Gojwane Central 30 Goo - Sekgweng Bag 29 Palapye Goo-Sekgweng 4918380 Central 31 Goo-Tau Bag 84 Palapye Goo - Tau 4950117 -

CITIES/TOWNS and VILLAGES Projections 2020

CITIES/TOWNS AND VILLAGES Projections 2020 Private Bag 0024, Gaborone Tel: 3671300 Fax: 3952201 Toll Free: 0800 600 200 Private Bag F193, City of Francistown Botswana Tel. 241 5848, Fax. 241 7540 Private Bag 32 Ghanzi Tel: 371 5723 Fax: 659 7506 Private Bag 47 Maun Tel: 371 5716 Fax: 686 4327 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.statsbots.org.bw Cities/Towns And Villages Projections 2020 Published by Statistics Botswana Private Bag 0024, Gaborone Website: www.statsbots.org.bw E-mail: [email protected] Contact: Census and Demography Analysis Unit Tel: (267) 3671300 Fax: (267) 3952201 November, 2020 COPYRIGHT RESERVED Extracts may be published if source Is duly acknowledged Cities/Towns and Villages Projections 2020 Preface This stats brief provides population projections for the year 2020. In this stats brief, the reference point of the population projections was the 2011 Population and Housing Census, in which the total population by age and sex is available. Population projections give a picture of what the future size and structure of the population by sex and age might look like. It is based on knowledge of the past trends, and, for the future, on assumptions made for three components of population change being fertility, mortality and migration. The projections are derived from mathematical formulas that use current populations and rates of growth to estimate future populations. The population projections presented is for Cities, Towns and Villages excluding associated localities for the year 2020. Generally, population projections are more accurate for large populations than for small populations and are more accurate for the near future than the distant future.