The Self in Black and White Interfaces: Studies in Visual Culture Editors Mark J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Full Resource List

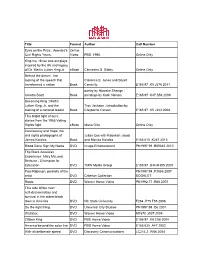

Title Format Author Call Number Eyes on the Prize : America's Online Civil Rights Years. Video PBS, 1990. Online Only King me : three one-act plays inspired by the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. eBook Clinnesha D. Sibley. Online Only Behind the dream : the making of the speech that Clarence B. Jones and Stuart transformed a nation Book Connelly. E185.97 .K5 J576 2011 poetry by Ntozake Shange ; Coretta Scott Book paintings by Kadir Nelson. E185.97 .K47 S53 2009 Becoming King : Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Troy Jackson ; introduction by making of a national leader Book Clayborne Carson. E185.97 .K5 J343 2008 This bright light of ours: stories from the 1965 Voting Rights fight eBook Maria Gitin. Online Only Controversy and Hope: the civil rights photographs of Julian Cox with Rebekah Jacob James Karales Book and Monica Karales E185.615 .K287 2013 Blood Done Sign My Name DVD Image Entertainment PN1997.99 .B59645 2010 The Black American Experience: Mary McLeod Bethune - Champion for Education DVD TMW Media Group E185.97 .B34 M385 2009 Paul Robeson: portraits of the PN1997.99 .P3885 2007 artist DVD Criterion Collection BOOKLET Roots DVD Warner Home Video PN1992.77 .R66 2007 This side of the river: self-determination and survival in the oldest black town in America DVD NC State University F264 .P75 T55 2006 Do the right thing DVD Universal City Studios PN1997.99 .D6 2001 Wattstax DVD Warner Home Video M1670 .W37 2004 Citizen King DVD PBS Home Video E185.97 .K5 C58 2004 America beyond the color line DVD PBS Home Video E185.625 .A47 2003 With all deliberate speed DVD Discovery Communications LC214.2 .W58 2004 Chisholm '72: Unbought and 20th Century Fox Home Unbossed DVD Entertainmen E840.8 .C48 C55 2004 Between the World and Me Book Ta-Nehisi Coates E185.615 .C6335 2015 The autobiography of Malcolm X Book Malcolm X E185.97 .L5 A3 2015 Dreams from my father : a story of race and inheritance Book Barack Obama E185.97 .O23 A3 2007 Up from slavery : an autobiography Book Booker T. -

Tips for Families

GRADE 2 | MODULE 3 TIPS FOR FAMILIES WHAT IS MY GRADE 2 STUDENT LEARNING IN MODULE 3? Wit & Wisdom® is our English curriculum. It builds knowledge of key topics in history, science, and literature through the study of excellent texts. By reading and responding to stories and nonfiction texts, we will build knowledge of the following topics: Module 1: A Season of Change Module 2: The American West Module 3: Civil Rights Heroes Module 4: Good Eating In Module 3, we will study a number of strong and brave people who responded to the injustice they saw and experienced. By analyzing texts and art, students answer the question: How can people respond to injustice? OUR CLASS WILL READ THESE BOOKS Picture Books (Informational) ▪ Martin Luther King, Jr. and the March on Washington, Frances E. Ruffin; illustrations, Stephen Marchesi ▪ I Have a Dream, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; paintings, Kadir Nelson ▪ Ruby Bridges Goes to School: My True Story, Ruby Bridges ▪ The Story of Ruby Bridges, Robert Coles; illustrations, George Ford ▪ Separate is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation, Duncan Tonatiuh Poetry ▪ “Words Like Freedom,” Langston Hughes ▪ “Dreams,” Langston Hughes OUR CLASS WILL EXAMINE THIS PHOTOGRAPH ▪ Selma to Montgomery March, Alabama, 1965, James Karales OUR CLASS WILL READ THESE ARTICLES ▪ “Different Voices,” Anna Gratz Cockerille ▪ “When Peace Met Power,” Laura Helwegs OUR CLASS WILL WATCH THESE VIDEOS ▪ “Ruby Bridges Interview” ▪ “Civil Rights – Ruby Bridges” ▪ “The Man Who Changed America” For more resources, -

FIAP Yearbooks of Photography, 1954–1960 Alise Tifentale, The

The “Cosmopolitan Art”: FIAP Yearbooks of Photography, 1954–1960 Alise Tifentale, The Graduate Center, City University of New York [Research paper presented at the CAA 2017 in New York City, February 17, 2017, at the session “Photography in Print.”] “It is a diversified, yet tempered picture book containing surprises on every page, a mirror to pulsating life, a rich fragment of cosmopolitan art, a pleasure ground of phantasy”—this is how, in March 1956, the editorial board of Camera magazine introduced the latest photography yearbook by the International Federation of Photographic Art (Fédération internationale de l'art photographique, FIAP). By examining the first four FIAP Yearbooks, published between 1954 and 1960 on a biennial basis,1 this paper aims to reconstruct some of the ideals behind the work of FIAP and to understand the “cosmopolitan art” of photography promoted by this organization. FIAP, a non-governmental and transnational association, was founded in Switzerland in 1950 and aimed at uniting the world’s photographers. It consisted of national associations of photographers, representing 55 countries: seventeen in Western Europe, thirteen in Asia, ten in Latin America, six in Eastern Europe, four in Middle East, three in Africa, one in North America, and Australia. As with many non-governmental organizations established around 1950, its membership was global, but the founders and leaders were based in Western Europe— Belgium, Switzerland, France, and West Germany. FIAP epitomized the postwar idealism which it shared with organizations such as UN or UNESCO. “The black and white art (..) through its truthfulness also stimulates one to 1 Three more FIAP yearbooks were published in 1962, 1964, and 1966. -

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008 Jan

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008 Jan. 31 – May 31, 2015 Exhibition Checklist DOWN AT CONEY ISLE, 1861-94 1. Sanford Robinson Gifford The Beach at Coney Island, 1866 Oil on canvas 10 x 20 inches Courtesy of Jonathan Boos 2. Francis Augustus Silva Schooner "Progress" Wrecked at Coney Island, July 4, 1874, 1875 Oil on canvas 20 x 38 1/4 inches Manoogian Collection, Michigan 3. John Mackie Falconer Coney Island Huts, 1879 Oil on paper board 9 5/8 x 13 3/4 inches Brooklyn Historical Society, M1974.167 4. Samuel S. Carr Beach Scene, c. 1879 Oil on canvas 12 x 20 inches Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts, Bequest of Annie Swan Coburn (Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn), 1934:3-10 5. Samuel S. Carr Beach Scene with Acrobats, c. 1879-81 Oil on canvas 6 x 9 inches Collection Max N. Berry, Washington, D.C. 6. William Merritt Chase At the Shore, c. 1884 Oil on canvas 22 1/4 x 34 1/4 inches Private Collection Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art Page 1 of 19 Exhibition Checklist, Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861 – 2008 12-15-14-ay 7. John Henry Twachtman Dunes Back of Coney Island, c. 1880 Oil on canvas 13 7/8 x 19 7/8 inches Frye Art Museum, Seattle, 1956.010 8. William Merritt Chase Landscape, near Coney Island, c. 1886 Oil on panel 8 1/8 x 12 5/8 inches The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, N.Y., Gift of Mary H. Beeman to the Pruyn Family Collection, 1995.12.7 9. -

An Exhibition of B&W Argentic Photographs by Olivier Meyer

An exhibition of b&w argentic photographs by Olivier Meyer Location Gonville & Caius College, Trinity Street, Cambridge Exhibition 29 & 30 September 2018 10 am—5 pm Contact [email protected] Avenue du Président Wilson. 1987 Olivier Meyer, photographer Olivier Meyer is a contemporary French photographer born in 1957. He lives and works in Paris, France. His photo-journalism was first published in France-Soir Magazine and subsequently in the daily France-Soir in 1981. Starting from 1989, a selection of his black and white photographs of Paris were produced as postcards by Éditions Marion Valentine. He often met the photographer Édouard Boubat on the île Saint-Louis in Paris and at the Publimod laboratory in the rue du Roi de Sicile. Having seen his photographs, Boubat told him: “at the end of the day, we are all doing the same thing...” When featured in the magazine Le Monde 2 in 2007 his work was noticed by gallery owner Charles Zalber who exhibited his photographs at the gallery Photo4 managed by Victor Mendès. Work His work is in the tradition of humanist photography and Street photography, using the same material as many of the forerunners of this style: Kodak Tri-X black and white film, silver bromide prints on baryta paper, Leica M3 or Leica M4 with a 50 or 90 mm lens. The thin black line surrounding the prints shows that the picture has not been cropped. His inspiration came from Henri Cartier-Bresson, Édouard Boubat, Saul Leiter. His portrait of Aguigui Mouna sticking his tongue out like Albert Einstein, published in postcard form in 1988, and subsequently as an illustration in a book by Anne Gallois served as a blueprint for a stencil work by the artist Jef Aérosol in 2006 subsequently reproduced in the book VIP. -

Jerry Uelsmann by Sarah J

e CENTER FOR CREATIVE PHOTOGRAPHY • UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA RESEARCH SERIES NUMBER 15 JANUARY 1982 DEAN BROWN Contents The Dean Brown Archive 3 by James L. Enyeart An Appreciation 5 by Carol Brown Dean Brown: An Overview by Susan E. Ruff 6 Dean Brown: 11 A Black-and-White Portfolio Dean Brown: 25 A Color Portfolio Exhibitions of the Center 45 1975-1981 by Nancy D. Solomon Acquisitions Highlight: 51 Jerry Uelsmann by Sarah J. Moore Acquisitions: 54 July-December 1980 compiled by Sharon Denton The Archive, Research Series, is a continuation of the research publication entitled Cmter for Creative Photography; there is no break in the consecutive numbering of issues. The A ,chive makes available previously unpublished or unique material from the collections in the Archives of the Center for Creative Photography. Subscription and renewal rate: $20 (USA), S30 (foreign), for four issues. Some back issues are available. Orders and inquiries should be addressed to: Subscriptions Center for Creative Photography University of Arizona 843 E. University Blvd. Tucson, Arizona 85719 Center for Creative Photography University of Arizona Copyright © 1982 Arizona Board of Regents All Rights Reserved Photographs by Dean Brown Copyright ©1982 by Carol Brown Designed by Nancy Solomon Griffo Alphatype by Morneau Typographers Laser-Scanned Color Separations by American Color Printed by Prisma Graphic Bound by Roswell Bookbinding The Archive, Research Series, of the Center for Creative Photography is supported in part by Polaroid Corporation. Plate 31 was reproduced in Cactus Country, a volume in the Time Life Book series-The American Wilderness. Plates 30, 34, and 37 were reproduced in Wild Alaska from the same series. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

THE CRITICISM OF ROBERT FRANK'S "THE AMERICANS" Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alexander, Stuart Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 11:13:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/277059 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. -

William Gropper's

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas March – April 2014 Volume 3, Number 6 Artists Against Racism and the War, 1968 • Blacklisted: William Gropper • AIDS Activism and the Geldzahler Portfolio Zarina: Paper and Partition • Social Paper • Hieronymus Cock • Prix de Print • Directory 2014 • ≤100 • News New lithographs by Charles Arnoldi Jesse (2013). Five-color lithograph, 13 ¾ x 12 inches, edition of 20. see more new lithographs by Arnoldi at tamarind.unm.edu March – April 2014 In This Issue Volume 3, Number 6 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Fierce Barbarians Associate Publisher Miguel de Baca 4 Julie Bernatz The Geldzahler Portfoio as AIDS Activism Managing Editor John Murphy 10 Dana Johnson Blacklisted: William Gropper’s Capriccios Makeda Best 15 News Editor Twenty-Five Artists Against Racism Isabella Kendrick and the War, 1968 Manuscript Editor Prudence Crowther Shaurya Kumar 20 Zarina: Paper and Partition Online Columnist Jessica Cochran & Melissa Potter 25 Sarah Kirk Hanley Papermaking and Social Action Design Director Prix de Print, No. 4 26 Skip Langer Richard H. Axsom Annu Vertanen: Breathing Touch Editorial Associate Michael Ferut Treasures from the Vault 28 Rowan Bain Ester Hernandez, Sun Mad Reviews Britany Salsbury 30 Programs for the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre Kate McCrickard 33 Hieronymus Cock Aux Quatre Vents Alexandra Onuf 36 Hieronymus Cock: The Renaissance Reconceived Jill Bugajski 40 The Art of Influence: Asian Propaganda Sarah Andress 42 Nicola López: Big Eye Susan Tallman 43 Jane Hammond: Snapshot Odyssey On the Cover: Annu Vertanen, detail of Breathing Touch (2012–13), woodcut on Maru Rojas 44 multiple sheets of machine-made Kozo papers, Peter Blake: Found Art: Eggs Unique image. -

2016 in the United States Wikipedia 2016 in the United States from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

4/30/2017 2016 in the United States Wikipedia 2016 in the United States From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Events in the year 2016 in the United States. Contents 1 Incumbents 1.1 Federal government 1.2 Governors 1.3 Lieutenant governors 2 Events 2.1 January 2.2 February 2.3 March 2.4 April 2.5 May 2.6 June 2.7 July 2.8 August 2.9 September 2.10 October 2.11 November 2.12 December 3 Deaths 3.1 January 3.2 February 3.3 March 3.4 April 3.5 May 3.6 June 3.7 July 3.8 August 3.9 September 3.10 October 3.11 November 3.12 December 4 See also 5 References Incumbents Federal government President: Barack Obama (DIllinois) Vice President: Joe Biden (DDelaware) Chief Justice: John Roberts (New York) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2016_in_the_United_States 1/60 4/30/2017 2016 in the United States Wikipedia Speaker of the House of Representatives: Paul Ryan (RWisconsin) Senate Majority Leader: Mitch McConnell (RKentucky) Congress: 114th https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2016_in_the_United_States 2/60 4/30/2017 2016 in the United States Wikipedia Governors and Lieutenant governors Governors Governor of Alabama: Robert J. Bentley Governor of Mississippi: Phil Bryant (Republican) (Republican) Governor of Alaska: Bill Walker Governor of Missouri: Jay Nixon (Independent) (Democratic) Governor of Arizona: Doug Ducey Governor of Montana: Steve Bullock (Republican) (Democratic) Governor of Arkansas: Asa Hutchinson Governor of Nebraska: Pete Ricketts (Republican) (Republican) Governor of California: Jerry Brown Governor of Nevada: Brian Sandoval (Democratic) -

Intensify the Effort in 1964

INTENSIFY THE EFFORT IN 1964 Because of our action we have had some victories since I960 but many setbacks. The South's public transportation system is nearer to complete desegregation than any other :areg thanks to the Freedom Rides, which involved both northern and southern students. Their has been some lull in activities in local protest movements in the South since the March On Washington. Many people believe that the Movement is over and that its goals have been achieved - th?sy%re wrong ! The Movement is finding new directions; those involved are increasing in their own understand ing of which goals are most important in short-range and long-range terms.fc To illustrate the fact that the Movement is aiming at freedom in all areas, we feel it is necessary to expand our efforts in 1964. As a first step let us move with new and creative methods and techniques of fighting employment bias, of fighting those racists who have a political and economic stronghold on the American scene; and finally, new ways to protest against the unjust system of segregation For example, the Washington D. C. Nonviolent Action Group (NAG), affiliated with Snick, will be holding a massive demonstration on Capital Hill on January 31 demanding jobs for you, expanded home rule, improvement of housing and working conditions for those in the Capital|s ghetto. We hope that all communities across the nation will help us to expand the Movement in 1964 by carrying out the following action of February 1st: (1) organize mass marches on City Hall protesting policeyfeorutality and demanding the right for decent jobs and the right to vote (2) picket local federal buildings for passage of a strong Civil Rights Bill and the right to vote (3)- renew demonstrations in all areas demanding an open city and an open community (4)- organize a one-day boycott of schools to take place between February 1st and February 11. -

Contemporary Black & White Print Editions

Contemporary! Black & White ! Print Editions Effective March, 2015 Note: All listed editions are twenty (20) silver gelatin prints, printed between 2009 and the present. Print sizes refer to paper size; image size varies. Images are printed with a minimum one inch border to allow for archival framing. Additional sizes may be available upon request. Please contact the studio for date printed, image size and current edition numbers for specific prints. Vintage and Printed Later prints may be available for these and other images; please contact the studio for details. About Harold Feinstein Harold Feinstein was born in Coney Island, New York, in 1931 and began his photography career in 1946 at the age of 15. When he was 17, he joined the Photo League. At 19, Edward Steichen purchased his work for the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art. He is best known for his six-decade love affair with Coney Island as well as traditional street photography and photos from the Korean War. In addition to small camera black and white, Feinstein has a large collection of 35mm and digital color imagery. In 1998, Feinstein broke new ground as one of the pioneers of scanography, for which he was awarded the Computerworld Smithsonian Award in 2000. His most recent of eight books, Harold Feinstein: A Retrospective (Nazraeli, 2012) was a winner of the PDN Photo Annual 2013 Photo Book award. His photographs have been exhibited in and are represented in the permanent collections of major museums including MOMA, International Center of Photography, George Eastman House, Center for Creative Photography, The Jewish Museum and Museum of the City of New York. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography.