The University of Chicago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

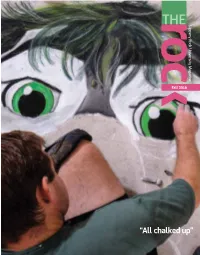

“All Chalked Up” Chalked “All View from the ROCK

Slippery University Rock Magazine Fall 2016 “All chalked up” View from the ROCK Dear Friends, I love this time of year when warm evenings melt into cool nights, and the aroma of autumn is in the air; but it’s also hard to say goodbye to summer. The summer of 2016 will be remembered as one of the busiest construction seasons on record at Slippery Rock University. Jackhammers, excavators and demolition crews were a common sight as crews worked diligently to renovate academic buildings, athletic fields and residence halls prior to the start of the fall semester. All of the work was scheduled with an eye toward modernizing academic learning environments and improving the appearance and function of buildings and campus. By the time classes resumed Aug. 29, $6.5 million in improvements had been completed. Major projects included a new entryway for Rhoads Hall; the demolition and reconstruction of the south wall at Spotts World Culture Building; the removal and resurfacing of the outdoor track at Mihalik-Thompson Stadium; and a pair of projects at Morrow Field House that included refinishing the basketball/ volleyball court and a roof replacement. In a continuing effort to extend our commitment to diversity, equality and inclusion, we converted more than 70 single- occupancy restrooms to all-gender restrooms. We also FALL 2016 Volume 18, Number 3 launched the Physician Assistant Program; opened the renovated Harrisville building and welcomed the Pokémon craze to campus. We were honored this summer to receive a number of In this issue national, regional and state awards for academic quality, value and sustainability among others. -

Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited Control of Music on Hold and Public Performance Rights Schedule 2

PHONOGRAPHIC PERFORMANCE COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED CONTROL OF MUSIC ON HOLD AND PUBLIC PERFORMANCE RIGHTS SCHEDULE 2 001 (SoundExchange) (SME US Latin) Make Money Records (The 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 100% (BMG Rights Management (Australia) Orchard) 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) Music VIP Entertainment Inc. Pty Ltd) 10065544 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 441 (SoundExchange) 2. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) NRE Inc. (The Orchard) 100m Records (PPL) 777 (PPL) (SME US Latin) Ozner Entertainment Inc (The 100M Records (PPL) 786 (PPL) Orchard) 100mg Music (PPL) 1991 (Defensive Music Ltd) (SME US Latin) Regio Mex Music LLC (The 101 Production Music (101 Music Pty Ltd) 1991 (Lime Blue Music Limited) Orchard) 101 Records (PPL) !Handzup! Network (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) RVMK Records LLC (The Orchard) 104 Records (PPL) !K7 Records (!K7 Music GmbH) (SME US Latin) Up To Date Entertainment (The 10410Records (PPL) !K7 Records (PPL) Orchard) 106 Records (PPL) "12"" Monkeys" (Rights' Up SPRL) (SME US Latin) Vicktory Music Group (The 107 Records (PPL) $Profit Dolla$ Records,LLC. (PPL) Orchard) (SME US Latin) VP Records - New Masters 107 Records (SoundExchange) $treet Monopoly (SoundExchange) (The Orchard) 108 Pics llc. (SoundExchange) (Angel) 2 Publishing Company LCC (SME US Latin) VP Records Corp. (The 1080 Collective (1080 Collective) (SoundExchange) Orchard) (APC) (Apparel Music Classics) (PPL) (SZR) Music (The Orchard) 10am Records (PPL) (APD) (Apparel Music Digital) (PPL) (SZR) Music (PPL) 10Birds (SoundExchange) (APF) (Apparel Music Flash) (PPL) (The) Vinyl Stone (SoundExchange) 10E Records (PPL) (APL) (Apparel Music Ltd) (PPL) **** artistes (PPL) 10Man Productions (PPL) (ASCI) (SoundExchange) *Cutz (SoundExchange) 10T Records (SoundExchange) (Essential) Blay Vision (The Orchard) .DotBleep (SoundExchange) 10th Legion Records (The Orchard) (EV3) Evolution 3 Ent. -

Kyle Bob Guitar (More Music on the Back!)

Kyle Bob Guitar (more music on the back!) Alt Rock Ed Sheeran – Perfect Lady Gaga – Million Reasons Elvis - Can't Help Falling in Love Lil Nas X – Old Town Road All American Rejects – Gives You Hell Eric Clapton – Wonderful Tonight Lorde – Royals Bastille - Pompeii Fleetwood Mac – Landslide Maroon 5 – This Love Matt Kearney – Ships In the Night Bastille/Marshmello – Happier Gary Jules – Mad World M.I.A. - Paper Planes Coldplay – Viva La Vida Israel K. - Somewhere over the MGMT – Kids Counting Crows – Accidentally in Rainbow Miley Cyrus - Wrecking Ball Love Jack Johnson – Banana Pancakes One Republic – Apologize Fallout Boy – Sugar We're Goin' Down Jack Johnson – Upside Down Pharell – Happy Fitz and The Tantrums - Out of My James Taylor – How Sweet It Is to Be Postal Service – Such Great Heights Lea g u e Loved Rihanna - Umbrella Foo Fighters – Best of You Jason Mraz – I'm Yours Shawn Mendes – In My Blood Foster The People – Pumped Up Kicks John Mayer – Gravity Shawn Mendes – Stitches Sia – Chandelier Green Day – Boulevard of Broken John Mayer – Waiting on the World to Taylor Swift – Blank Space Dre a m s Ch a n g e The Fray – Over my Head Hozier – Take Me to Church Jim Croce – Time in a Bottle The Greatest Showman – A Million Jimmy Eat World – The Middle John Denver - Country Roads Dre a m s Kings of Leon - Use Somebody John Lennon – Imagine Train – Hey Soul Sister Linkin Park – Numb Lifehouse – You and Me Twentyonepilots - Stressed Out Mumford and Sons – The Cave Michael Buble – Everything Twentyonepilots - Ride My Chemical Romance – -

2016 in the United States Wikipedia 2016 in the United States from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

4/30/2017 2016 in the United States Wikipedia 2016 in the United States From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Events in the year 2016 in the United States. Contents 1 Incumbents 1.1 Federal government 1.2 Governors 1.3 Lieutenant governors 2 Events 2.1 January 2.2 February 2.3 March 2.4 April 2.5 May 2.6 June 2.7 July 2.8 August 2.9 September 2.10 October 2.11 November 2.12 December 3 Deaths 3.1 January 3.2 February 3.3 March 3.4 April 3.5 May 3.6 June 3.7 July 3.8 August 3.9 September 3.10 October 3.11 November 3.12 December 4 See also 5 References Incumbents Federal government President: Barack Obama (DIllinois) Vice President: Joe Biden (DDelaware) Chief Justice: John Roberts (New York) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2016_in_the_United_States 1/60 4/30/2017 2016 in the United States Wikipedia Speaker of the House of Representatives: Paul Ryan (RWisconsin) Senate Majority Leader: Mitch McConnell (RKentucky) Congress: 114th https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2016_in_the_United_States 2/60 4/30/2017 2016 in the United States Wikipedia Governors and Lieutenant governors Governors Governor of Alabama: Robert J. Bentley Governor of Mississippi: Phil Bryant (Republican) (Republican) Governor of Alaska: Bill Walker Governor of Missouri: Jay Nixon (Independent) (Democratic) Governor of Arizona: Doug Ducey Governor of Montana: Steve Bullock (Republican) (Democratic) Governor of Arkansas: Asa Hutchinson Governor of Nebraska: Pete Ricketts (Republican) (Republican) Governor of California: Jerry Brown Governor of Nevada: Brian Sandoval (Democratic) -

The Timber Wars October 1, 8:30Pm

October 2020 October 2020 PRIMETIME PRIMETIME Oregon Field Guide The Timber Wars October 1, 8:30pm Photo courtesy of Beth Nakamura/The Oregonian primetime 1 THURSDAY 3 SATURDAY 7:00 OPB PBS NewsHour (Also Fri 12am) | 5:00 OPB This Old House Designing Kitchens OPB+ This Old House Westerly/A Ranch (Also Mon 6pm) | OPB+ Marathon Lucky Out Westerly Chow, continued (until 7pm) 7:30 OPB+ Ask This Old House Sliding Barn 5:30 OPB PBS NewsHour Weekend Door/Drywell 6:00 OPB Autumnwatch New England 8:00 OPB Oregon Art Beat Woven Together. 7:00 OPB Rick Steves’ Egypt: Yesterday & The Bautista family brings four generations of Today Experience the historic and cultural weaving tradition to Oregon. (Also Sun wonders of Egypt. (Also Mon 8pm OPB+) | 6pm) | OPB+ Secrets of the Dead King Timber Wars: OPB+ Samurai Wall A stonemason revives Arthur’s Lost Kingdom. Evidence may support ancient techniques. 30 Years of Confl ict the King Arthur legend. (Also Sat 12am) 8:00 OPB Frankie Drake Mysteries Out of Thirty years ago, the northern 8:30 OPB Oregon Field Guide The Timber Focus. The team visits a silent movie set. spotted owl was declared Wars. It’s been 30 years since the spotted (Also Mon 12am) | OPB+ Neanderthal (Also threatened under the Endangered owl was listed as a threatened species Sun 2am OPB+) and logging was curtailed throughout the Species Act, galvanizing a fi ght Northwest. What’s happened since? 9:00 OPB London: 2000 Years of History over the Pacifi c Northwest’s old (Also Sun 6:30pm) Learn how an uninhabitable swamp became growth forests. -

Intensify the Effort in 1964

INTENSIFY THE EFFORT IN 1964 Because of our action we have had some victories since I960 but many setbacks. The South's public transportation system is nearer to complete desegregation than any other :areg thanks to the Freedom Rides, which involved both northern and southern students. Their has been some lull in activities in local protest movements in the South since the March On Washington. Many people believe that the Movement is over and that its goals have been achieved - th?sy%re wrong ! The Movement is finding new directions; those involved are increasing in their own understand ing of which goals are most important in short-range and long-range terms.fc To illustrate the fact that the Movement is aiming at freedom in all areas, we feel it is necessary to expand our efforts in 1964. As a first step let us move with new and creative methods and techniques of fighting employment bias, of fighting those racists who have a political and economic stronghold on the American scene; and finally, new ways to protest against the unjust system of segregation For example, the Washington D. C. Nonviolent Action Group (NAG), affiliated with Snick, will be holding a massive demonstration on Capital Hill on January 31 demanding jobs for you, expanded home rule, improvement of housing and working conditions for those in the Capital|s ghetto. We hope that all communities across the nation will help us to expand the Movement in 1964 by carrying out the following action of February 1st: (1) organize mass marches on City Hall protesting policeyfeorutality and demanding the right for decent jobs and the right to vote (2) picket local federal buildings for passage of a strong Civil Rights Bill and the right to vote (3)- renew demonstrations in all areas demanding an open city and an open community (4)- organize a one-day boycott of schools to take place between February 1st and February 11. -

Current Market Prices ~ Prints, Sculpture, Originals

Issue TITLE Price, Low SIZE Retail, ISSUE LO High HI TITLE Retail (December SIZE ISSUE LO2014) HI TITLE SIZE ISSUE LO HI CURRENT MARKET PRICES ~ PRINTS, SCULPTURE, ORIGINALS Prints, Graphics, & Giclées Prices do not reflect shifts below a print's original issue price TITLE SIZE ISSUE LO HI TITLE SIZE ISSUE LO HI TITLE SIZE ISSUE LO HI ABBETT, ROBERT AMIDON, SUSAN ATKINSON, MICHAEL BIG GUY SETTER & GROUS 125 553 671 CATHEDRAL ST PAUL CE 125 409 497 GRANNYS LOVING HAND AP 420 510 BOBWHITES & POINTER 50 152 190 COMO PARK CONSERVAT AP 21X29 158 198 GRANNYS LOVING HANDS 385 467 CODY BLACK LAB 95 152 190 COMO PARK CONSERVATORY 21X29 125 125 125 ICE BLUE DIPTYCH 125 262 315 CROSSING SPLIT ROCK 125 125 150 COMO PARK GOLF SKI 21X15 100 100 120 INSPIRATION ARCHES 185 185 185 ABBOTT, LEN COMO PARK PAVILLION 125 698 848 INSPIRATION ARCHES AP 152 190 CHORUS 292 351 GOVERNORS MANSION 99 124 LETTERS FROM GRANDMA 65 152 190 ACHEFF, WILLIAM GOVERNORS MANSION AP 136 170 LONG WAY HOME 148 185 ACOMA 23X18 200 200 200 LAKE HARRIET 24X18 125 125 125 MARIAS HANDS SR 24X18 861 1060 STILL LIFE 64 80 LITTLE FRENCH CHURC AP 21X15 110 138 MONUMENT CANYON SR 33X45 490 595 ADAMS, GAIL LITTLE FRENCH CHURCH 21X15 100 100 100 MOONLIT CANYON 165 165 165 DOUBLE SOLITUDE AP 275 275 315 LORING PARK HARMON AP 29X21 158 198 MOUNTAIN LAKE 18X24 175 258 310 SLEEPIN BEAUTY 225 225 225 MINN STATE CAPITOL 21X16 187 225 ON WALDEN 150 150 150 ADAMS, HERMON MT OLIVET CHURCH 158 198 ON WALDEN AP 94 118 ARIZONA RANGER 120 1072 1320 NICOLLET AVE AP 20X25 78 98 OSTUNI 29X22 150 150 183 -

Communities Fight Africa's Poaching Crisis by Protecting Wildlife for Future

Communities fight Africa’s poaching crisis by protecting wildlife for future generations Director/Cinematographer: Mirra Bank Producers: Richard Brockman, Mirra Bank A production of Nobody’s Girls, Inc. c.2020 CONTACT Mirra Bank [email protected] // 917-699-6059 SYNOPSIS No Fear No Favor illuminates the wrenching choices faced by rural Africans who live where community meets wilderness—on the front lines of Africa’s poaching crisis. Filmed over several years in Zambia’s vast Kafue National Park, as well as in North Kenya and Namibia, the film follows local women and men who fight the illegal wildlife trade through both cooperative law enforcement and community-led conservation that sustains wildlife, returns profit to local people, and generates new livelihoods. No Fear No Favor reveals that when the connection between poverty and poaching is disrupted - people and wildlife can thrive equally, side by side. MIRRA BANK Mirra Bank’s work has been screened and celebrated internationally. A selection Director of her previous features include: The Only Real Game (Netflix premiere), Best Producer Documentary, NYIFF; American Spirit Award, Sedona Film Festival; Last Dance Cinematographer (Sundance Channel), short-listed for an Academy Award, Golden Gate Award, SFIFF; American Film Institute Ten Best Docs of the year; Nobody’s Girls, (PBS non-fiction special) Cine Gold- en Eagle, Chris Award; Enormous Changes (ABC Video, BBC, Sky Channel), premiered at Sundance and Toronto, international theatri- cal release. Bank is a member of the Documentary Branch of the Acad- emy, a MacDowell Fellow, a found- ing member of New Day Films. She serves on the Advisory Board of the Bronx Documentary Cen- ter, and on the Board of Directors of the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures. -

NEXT ISSUE JUNE 29Th We Thank

To the men and women who died for our freedom: THE We Thank You SOUTH AMBOY ★★★★ SAYREVILLE Date: May 25, 2013 PRICELESS Vol. 22 Issue 8 Locals Honored Sayreville Police For Sandy Heroics Commended (Article submitted) Sayreville Police officers Sgt. Robert The prestigious Middlesex County 200 Lasko and Officer Joseph Monaco were re- Club honored South Amboy First Aid EMT’s cently honored by the Middlesex County 200 and firefighters with Meritorious Service Club at its annual banquet. The policemen Awards for their heroic actions on Oct. 29, 2012 during Hurricane Sandy. Receiving were commended for their actions during the awards were EMT’s, E.J. Campbell, the Pathmark shooting incident last year. Rob Sekerak, Gene Cox, and Mackenzie Congratulations on a fine job! Russell; Firefighters, Assistant Fire Chief Brett Coyle, LT Tom Szatkowski, LT Bill City Wide Yard Sale Tierney, FF Mike Coman, FF Tim Walczak. The Annual South Amboy City-wide Congratulations to all on your outstanding Yard Sale is scheduled for Saturday, June 22 work! nd , 2013 from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. All residents are welcome to participate, no registration Berman Featured is necessary. Great bargains, just look for the balloons at the participating homes. Any Sheila Berman,On aTV Special Education Pictured in front of South Amboy City Hall following the Memorial Day Parade and Memorial questions, please call 732-525-5932 or email teacher in the Sayreville schools system was Service are (l-r) Assemblyman Craig Coughlin, Asssemblyman John S. Wisniewski, American [email protected]. recently honored on the Kate Couric Show Legion Luke A. -

Outlaw Motorcycle Clubs and Organized Crime

Klaus von Lampe and Arjan Blokland Outlaw Motorcycle Clubs and Organized Crime ABSTRACT Outlaw motorcycle clubs have spread across the globe. Their members have been associated with serious crime, and law enforcement often perceives them to be a form of organized crime. Outlaw bikers are disproportionately engaged in crime, but the role of the club itself in these crimes remains unclear. Three scenarios describe possible relations between clubs and the crimes of their members. In the “bad apple” scenario, members individually engage in crime; club membership may offer advantages in enabling and facilitating offending. In the “club within a club” scenario, members engage in crimes separate from the club, but because of the number of members involved, including high-ranking members, the club itself appears to be taking part. The club can be said to function as a criminal organization only when the formal organizational chain of command takes part in organization of the crime, lower level members regard senior members’ leadership in the crime as legitimate, and the crime is generally understood as “club business.” All three scenarios may play out simultaneously within one club with regard to different crimes. Fact and fiction interweave concerning the origins, evolution, and prac- tices of outlaw motorcycle clubs. What Mario Puzo’s (1969) acclaimed novel The Godfather and Francis Ford Coppola’s follow-up film trilogy did for public and mafiosi perceptions of the mafia, Hunter S. Thompson’s Electronically published June 3, 2020 Klaus von Lampe is professor of criminology at the Berlin School of Economics and Law. Arjan Blokland is professor of criminology and criminal justice at Leiden University, Obel Foundation visiting professor at Aalborg University, and senior researcher at the Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement. -

Annual Report 2016 Welcome

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 WELCOME 9 Lunchtime Talks on 10 Saturday Special Tours 20 Family Art JAMs 10 Looking Inward 12 Eyes on Art Tours 7 Fun for the Young 9 exhibitions on 9 exhibitions on 10 exhibitions served 234 Meditative Art Tours served 122 visitors programs served served 148 visitors served 399 visitors children and 169 parents served 57 visitors 72 children and 52 adults The 80th anniversary of The Fralin Museum of Art at the remains on view in our Cornell Entrance Gallery. Jacob Lawrence: Struggle…From the History of the American People offered a unique look at this under studied series of the painter’s University of Virginia provided a remarkable platform that body of work. allowed the Museum to shine throughout 2015–2016. Richard Serra: Prints, generously loaned by the Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation, With engaging exhibitions and educational community programming drawing rave reviews, showcased the contemporary artist’s lithography, and Two Extraordinary Women: The Lives we are diligently working to bring new and diverse audiences through our doors. Our work and Art of Maria Cosway and Mary Darby Robinson, offered a compelling look at two complex attracts more than 25,000 annual visitors and this report aims to illustrate the impact and remarkable late 18th-century women, one of whom was closely connected to of our efforts through stories, statistics and photographs. Through this year-in-review, Thomas Jefferson. we hope to highlight the generosity of our donors, as well as the dedicated engagement of our volunteers, members and staff. Your hard work and support is making art a vital I extend my sincere thanks to M. -

QTCASW DEC11.Qxd:Layout 1 11/22/11 11:33 AM Page 1 QTCASW DEC11.Qxd:Layout 1 11/22/11 11:34 AM Page 2

QTCASW_DEC11.qxd:Layout 1 11/22/11 11:33 AM Page 1 QTCASW_DEC11.qxd:Layout 1 11/22/11 11:34 AM Page 2 2 DECEMBER 2011 03 - SPEEDBUMPS 06 - QT IN SHANGHAI 09 - BIKERS FORBOOBIES 11 - ARMY PICS FROM AFGHANISTAN 13 - LANE SHARING 14 - LOVE RIDE 28 17 - RIP’S BAD RIDE AZ 21 - WOMEN WHO RIDE 26 - HELP RIDE 29 - HARLEY X3 30 - FUTURE OF INDIAN 37 - BEHIND THE MAP: CHEYENNE CONTRIBUTORS: CHRIS DALGAARD LISA DALGAARD YOU, the Motorcycling Community MICHELE STEVEN ADAMO NATIONAL PUBLISHER & CA EDITOR ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER ART DIRECTOR CALIFORNIA Randy Twells Gary Mraz Art Hall Mel Jacobson Kevin DeCapite ARIZONA NEVADA Famous Jake “Wild Bill” Saxton Digger Dave George Childress Dangerous James TigerLily Cheryl Warren STAFF WRITERS: PHOTOGRAPHERS: CD, Randy Twells, Lisa Dalgaard, Mike Dalgaard, Art Hall, Ray Ambler, Ron Sinoy, CD, George Childress, Famous Jake, Tom "PIR8" Tinney, Ray Seidel, WEBMASTER Mike Sayer, Robert Sweeney, Art Hall, TigerLily, “Wild Bill” Saxton Kirk Johnson - phoenixbikers.com QTCASW_DEC11.qxd:Layout 1 11/22/11 11:34 AM Page 3 DECEMBER 2011 3 NEWS AND NOTES FROM AROUND BIKER LAND CHP reports decline in motorcycle-in- without these so called “outlaw” sales. He points out LONE STAR RALLY – that with a dramatic drop in overall motorcycle sales, 10 YEARS OLD AND GROWING volved collisions, injuries and a shortage of key new models, the loss of these sales would essentially put him out of business. Over Since when has the term “growing” been used to de- The California Highway Patrol reports that a two- the past three years his dealership has logged in some scribe a motorcycle rally these days? Virtually every year, federally funded program to increase motorists’ $8 Million dollars in annual sales.