Republic of Belarus Country Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lute Revival in Pinsk

CULTURE The Minsk Times Thursday, August 29, 2013 9 Film events developed Lute revival in Pinsk near Smorgon Unique Pinsk master restores ancient musical instruments while Brest actress Yanina Malinchik to play a leading role in Russian performing medieval music all over Brest Region filmDeath Battalion Igor Ugolnikov, the screenwriter and producer, tells us, “The fact that an actress from Brest was chosen for this role shows the special connec- tion with our last film:Brest Fortress. She proved her talent and character during film tests.” Death Battalion will be the larg- est Russian film project devoted to the First World War, being filmed with support from the Russian Min- istry of Culture. It is to provide 50 million Russian Roubles of the 250 million total budget. The film tells of a women’s de- tachment, created in St. Petersburg at the order of the 1917 provisional government, to raise the fighting spirit of the army. Events are being filmed near Smorgon, where this fe- male battalion fought heroically. Shooting begins on 31st August, with the premiere scheduled for 1st August, 2014, coinciding with the Me- morial Day for all those soldiers who died during the First World War. Experimental theatre scene BELTA By Lyudmila Ivanova Yury Dubnovitsky shares his love of ancient instrument with pupils Play by daughter of Charlie By Yuri Chernyakevich lute was made and, since then, Yuri lute as a promising instrument.” Mr. familiar with music will understand Chaplin being staged in Minsk has been producing new instruments. Dubnovitsky teaches pupils at the lo- that it’s a true challenge to learn to from 28th September to 21st Pinsk’s residents are now able to His work has made him well-known cal musical school, making them tune play the lute,” explains Mr. -

2008 Hate Crime Survey

2008 Hate Crime Survey About Human Rights First HRF’s Fighting Discrimination Program Human Rights First believes that building respect for human The Fighting Discrimination Program has been working since rights and the rule of law will help ensure the dignity to which 2002 to reverse the rising tide of antisemitic, racist, anti- every individual is entitled and will stem tyranny, extremism, Muslim, anti-immigrant, and homophobic violence and other intolerance, and violence. bias crime in Europe, the Russian Federation, and North America. We report on the reality of violence driven by Human Rights First protects people at risk: refugees who flee discrimination, and work to strengthen the response of persecution, victims of crimes against humanity or other mass governments to combat this violence. We advance concrete, human rights violations, victims of discrimination, those whose practical recommendations to improve hate crimes legislation rights are eroded in the name of national security, and human and its implementation, monitoring and public reporting, the rights advocates who are targeted for defending the rights of training of police and prosecutors, the work of official anti- others. These groups are often the first victims of societal discrimination bodies, and the capacity of civil society instability and breakdown; their treatment is a harbinger of organizations and international institutions to combat violent wider-scale repression. Human Rights First works to prevent hate crimes. For more information on the program, visit violations against these groups and to seek justice and www.humanrightsfirst.org/discrimination or email accountability for violations against them. [email protected]. Human Rights First is practical and effective. -

Military Cooperation Between Russia and Belarus: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives

ISSN 2335-870X LITHUANIAN ANNUAL STRATEGIC REVIEW 2019 Volume 17 231 Virgilijus Pugačiauskas* General Jonas Žemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania Military Cooperation between Russia and Belarus: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives The article analyses the dynamics of military cooperation between Russia and Belarus at the time when Russia’s aggression against Ukraine revealed president Vladimir Putin’s objective to consolidate control over his interest zone in the nearest post-soviet area at all hazards. This could be called the time-period during which endurance of military cooperation is increased and during which Rus- sia demonstrates its principle ambition to expand the use of military capabilities while leaning on Belorussian military capabilities, military infrastructure and territory as a bridgehead for potential military actions. For this reason, the aim of the paper is to outline the key factors which determine military integration of the both countries, or, more specifically, to discuss orientations and objectives set forth for building military cooperation as laid down in the documents regulating military policy, to discuss and assess practical cases of strengthening of interaction between military capabilities (stra- tegic military exercises), to reveal the accomplishments of military and technical cooperation, prob- lems it might pose and potential prospects of its development. Introduction In the relationship between Belarus and Russia, the field of military co- operation could be highlighted as the most stable over the past three decades, though the relationship of the both countries is accompanied by alleged, sta- ged and still emerging disagreements or flashes of short-term tension which notably remind of movement of meteors, which illuminate the sky, towards the sinful planet of Earth. -

The Story of Sarah from Ivatzevichi by Leonid Smilovitsky

The Story of Sarah from Ivatzevichi by Leonid Smilovitsky Sarah Kopeliansky of Ivatzevichi was the lone member The Kopelianskys spoke Yiddish and Polish. Bentzion of her immediate family to survive World War II. This story subscribed to Hebrew periodicals from Palestine, including recreates her pre-war life, recounts her service with partisans the newspaper Davar. The journals and newspaper files were fighting the Germans, and her fate to the present. Ivatzevichi bound and shared with friends. Benzoin never returned from belonged to Poland when she was born but is now located in Warsaw without gifts. To his daughter he brought sweets; to Belarus. his wife cuts of cloth, woolen fabric, fur collars for vests and dresses, even silver buttons. From the history of the townlet According to the Lithuanian Record, the estate of Ivatzevichi was transferred in 1519 to Jewish merchants from Grodno.1 From 1654 Ivatzevichi was known as the estate of Yan Victorian, Judge of Slonim, Elder of Skidel and Mosty. For a century it was part of the Slonim District, Novohrudok Province, in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. It was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1795. Not far off was “Merechevshchina,” the ancestral estate of Kosciusko.2 During 1863-1864, Ivatzevichi constituted part of the area involved in the uprising of Kastus Kalinovski against the Tsar’s government.3 The laying of the railroad from Brest to Moscow began next to Ivatzevichi in 1871. A small settlement arose where people engaged in forestry, ran a small distillery, a brick factory, and a water mill. During World War I, Ivatzevichi was occupied by the German armies of Kaiser Wilhelm II, and in 1919-1920 by those of Poland. -

Eastern Partnership Regional Transport Study

Eastern Partnership regional transport study TRACECA IDEAJune II 2015 Annex II – Thematic maps P a g e | 1 Transport Dialogue and THIS PROJECT IS FUNDED BY THE EU Networks Interoperability II Eastern Partnership regional transport study Final report Annex II – Thematic maps June 2015 This document is prepared by the IDEA II Project. The IDEA II Project is implemented by TRT Trasporti e Territorio in association with: Panteia Group, Dornier Consulting GmbH and Lutsk University Eastern Partnership regional transport study June 2015 Annex II – Thematic maps P a g e | 2 TABLE OF CONTENT 1 ANNEX II – THEMATIC MAPS ................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Rail maps................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Road maps ................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 Maps for Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova ........................................................................ 6 1.2 Maps for Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan ................................................................... 7 Eastern Partnership regional transport study June 2015 Annex II – Thematic maps P a g e | 3 1 ANNEX II – THEMATIC MAPS In the context of this assignment, a GIS database to display the collected indicators of the EaP transport network has been completed. The GIS database is based on the shapefiles (GIS files) of the EaP road and rail transport networks received -

ZRBG – Ghetto-Liste (Stand: 01.08.2014) Sofern Eine Beschäftigung I

ZRBG – Ghetto-Liste (Stand: 01.08.2014) Sofern eine Beschäftigung i. S. d. ZRBG schon vor dem angegebenen Eröffnungszeitpunkt glaubhaft gemacht ist, kann für die folgenden Gebiete auf den Beginn der Ghettoisierung nach Verordnungslage abgestellt werden: - Generalgouvernement (ohne Galizien): 01.01.1940 - Galizien: 06.09.1941 - Bialystok: 02.08.1941 - Reichskommissariat Ostland (Weißrussland/Weißruthenien): 02.08.1941 - Reichskommissariat Ukraine (Wolhynien/Shitomir): 05.09.1941 Eine Vorlage an die Untergruppe ZRBG ist in diesen Fällen nicht erforderlich. Datum der Nr. Ort: Gebiet: Eröffnung: Liquidierung: Deportationen: Bemerkungen: Quelle: Ergänzung Abaujszanto, 5613 Ungarn, Encyclopedia of Jewish Life, Braham: Abaújszántó [Hun] 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Kassa, Auschwitz 27.04.2010 (5010) Operationszone I Enciklopédiája (Szántó) Reichskommissariat Aboltsy [Bel] Ostland (1941-1944), (Oboltsy [Rus], 5614 Generalbezirk 14.08.1941 04.06.1942 Encyclopedia of Jewish Life, 2001 24.03.2009 Oboltzi [Yid], Weißruthenien, heute Obolce [Pol]) Gebiet Vitebsk Abony [Hun] (Abon, Ungarn, 5443 Nagyabony, 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Encyclopedia of Jewish Life 2001 11.11.2009 Operationszone IV Szolnokabony) Ungarn, Szeged, 3500 Ada 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Braham: Enciklopédiája 09.11.2009 Operationszone IV Auschwitz Generalgouvernement, 3501 Adamow Distrikt Lublin (1939- 01.01.1940 20.12.1942 Kossoy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Life 09.11.2009 1944) Reichskommissariat Aizpute 3502 Ostland (1941-1944), 02.08.1941 27.10.1941 USHMM 02.2008 09.11.2009 (Hosenpoth) Generalbezirk -

Byelorussian Chronicle 1967 I. the International Scene *

370 THE JOURNAL OF BYELORUSSIAN STUDIES Byelorussian Chronicle 1967 I. The International Scene I. GENERAL In May the Byelorussian delegate * to the United Nations L. Klackoŭ A Byelorussian delegation also took spoke at the General Assembly of the part in the sessions of the European need to grant immediate indepen Economic Commission of the United dence to South-West Africa. * Nations in Geneva. * In June a delegation, headed by A. Šeldaŭ, took part in the 51st session of On the 24th June the head of the the International Labour Organisation delegation to the United Nations A. in Geneva. Later in the year the Perm Hurynovič spoke at the General Assem anent Parliamentary Commission for bly in support of the Arab states in the Foreign Affairs (chairman L. Klackoŭ) Arab-Israeli armed conflict. He spoke recommended the Byelorussian Parl again in October in defence of the iament to ratify the ILO convention's economic interests of the nations resolution concerning the leisure time which had recently attained indepen of industrial workers. dence. II. INTERNATIONAL CULTURAL EXCHANGES T h e U n i t e d N a t i o n s Soviet pavillion. The highlight of the day was a concert given by the famous From November to the end of Byelorussian State Folk Instruments December an exhibition of Byelorus Orchestra under the direction of sian books was held in the United professor I. Žynovič, the Female Folk Nations Library in New York. Song Quartet, the singers Tamara * Šymko, Tamara Nižnikava, Arkadź Saŭčanka, Viktar Vujacič, the ballet A r m e n i a dancers L. -

Report by Kube on the Extermination of Jews and the Fight Against the Partisans in Belorussia

Report by Kube on the Extermination of Jews and the Fight Against the Partisans in Belorussia Minsk, July 31, 1942 The Generalkommissar for Belorussia Gauleiter / G 507/42 g To Reichskommissar for Ostland Gauleiter Hinrich Lohse Riga Secret Re: Combating Partisans and Aktion against Jews in the Generalbezirk of Belorussia In all the clashes with the partisans in Belorussia it has proved that Jewry, both in the formerly Polish, as well as in the formerly Soviet parts of the District General, is the main bearer of the partisan movement, together with the Polish resistance movement in the East and the Red Army from Moscow. In consequence, the treatment of Jewry in Belorussia is a matter of political importance owing to the danger to the entire economy. It must therefore be solved in accordance with political considerations and not merely economic needs. Following exhaustive discussions with the SS Brigadefuehrer Zenner and the exceedingly capable Leader of the SD, SS Obersturmbannfuehrer Dr. jur. Strauch, we have liquidated about 55,000 Jews in Belorussia in the past 10 weeks. In the area of Minsk county Jewry has been completely eliminated without any danger to the manpower requirements. In the predominantly Polish area of Lida, 16,000 Jews were liquidated, in Slonim, 8,000, etc. Owing to encroachment by the Army Rear Zone (Command), which has already been reported, there was interference with the preparations we had made for the liquidation of the Jews in Glebokie. Without contacting me, the Army Rear Zone Command liquidated 10,000 Jews, whose systematic elimination had in any case been planned by us. -

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

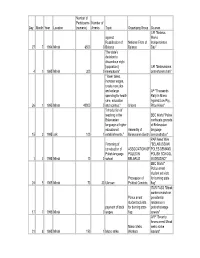

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

Download Book

84 823 65 Special thanks to the Independent Institute of Socio-Economic and Political Studies for assistance in getting access to archival data. The author also expresses sincere thanks to the International Consortium "EuroBelarus" and the Belarusian Association of Journalists for information support in preparing this book. Photos by ByMedia.Net and from family albums. Aliaksandr Tamkovich Contemporary History in Faces / Aliaksandr Tamkovich. — 2014. — ... pages. The book contains political essays about people who are well known in Belarus and abroad and who had the most direct relevance to the contemporary history of Belarus over the last 15 to 20 years. The author not only recalls some biographical data but also analyses the role of each of them in the development of Belarus. And there is another very important point. The articles collected in this book were written at different times, so today some changes can be introduced to dates, facts and opinions but the author did not do this INTENTIONALLY. People are not less interested in what we thought yesterday than in what we think today. Information and Op-Ed Publication 84 823 © Aliaksandr Tamkovich, 2014 AUTHOR’S PROLOGUE Probably, it is already known to many of those who talked to the author "on tape" but I will reiterate this idea. I have two encyclopedias on my bookshelves. One was published before 1995 when many people were not in the position yet to take their place in the contemporary history of Belarus. The other one was made recently. The fi rst book was very modest and the second book was printed on classy coated paper and richly decorated with photos. -

According to Chaim Weizmann's

Motal Pol. Motol, Bel. Моталь, [We] had our own house – one storey, with seven rooms and a kitchen some acres of land, chickens, two cows, a vegetable garden, a few – מאָטעלע .Yid fruit trees. So we had a supply of milk, and sometimes butter; we had fruit and vegetables in season; we had enough bread – which my mother baked herself; we had fish, and we had meat once a week – on the Sabbath. And there was always plenty of fresh air. Chaim Weizmann, Trial and Error. The Autobiography, Philadelphia 1949 Hebrew greeting ¶ Motal, the into the Slonim Province, then into the birthplace and childhood home of Lithuania Governorate, and from 1801, it Chaim Weizmann, the first president was made part of the Grodno Province of of Israel, is probably the only town in the Russian Empire. Belarus that has a sign with its name in Hebrew posted by the road leading out of The Jews of Motal ¶ In 1562, town. ¶ The earliest written mention of “a Jewish landlord and tax collector from Motal is found in the documents of the Kobryn Favish Yeskovich,” who leased Lithuanian Metrica from 1422, where the right to collect taxes on merchandise, it was referred to as a private estate in complained to Savostian Druzhylovitski the Principality of Pinsk. In 1520, it was that the ruler of the district did not allow the property of Prince Fyodor Ivanovich him to collect taxes in his town of Motal Yaroslavich, who later donated it to the and in the neighbouring villages. This Orthodox Church of the Assumption of document suggests that Jews collecting the Blessed Virgin Mary in Leszno. -

National Threat Assessment 2021

DEFENCE INTELLIGENCE STATE SECURITY AND SECURITY DEPARTMENT OF SERVICE UNDER THE REPUBLIC OF THE MINISTRY OF LITHUANIA NATIONAL DEFENCE NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT 2021 DEFENCE INTELLIGENCE STATE SECURITY AND SECURITY DEPARTMENT OF SERVICE UNDER THE REPUBLIC OF THE MINISTRY OF LITHUANIA NATIONAL DEFENCE NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT 2021 VILNIUS, 2021 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 FOREWORD 5 SUMMARY 8 NEW SECURITY CHALLENGES 12 REGIONAL SECURITY 17 MILITARY SECURITY 27 ACTIVITIES OF HOSTILE INTELLIGENCE AND SECURITY SERVICES 41 PROTECTION OF CONSTITUTIONAL ORDER 50 INFORMATION SECURITY 54 ECONOMIC AND ENERGY SECURITY 61 TERRORISM AND GLOBAL SECURITY 67 3 INTRODUCTION The National Threat Assessment by the State Security Department of the Republic of Lithuania (VSD) and the Defence Intelligence and Security Service under the Ministry of National Defence of the Republic of Lithuania (AOTD) is presented to the public in accordance with Articles 8 and 26 of the Law on Intelligence of the Republic of Lithuania. The document provides consolidated, unclassified assessment of threats and risks to national security of the Repub- lic of Lithuania prepared by both intelligence services. The document assesses events, processes and trends that correspond to the intelligence requirements approved by the State Defence Council. Based on them and considering the long-term trends affecting national security, the document provides the assessment of major challenges that the Lithuanian national security is to face in the near term (2021–2022). The assessments of long-term