{PDF} Psyche: V. 1: Inventions of the Other

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 2Nd Ed

Abraham Bloemaert (Gorinchem 1566 – 1651 Utrecht) How to cite Bakker, Piet. “Abraham Bloemaert” (2017). Revised by Piet Bakker (2019). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 2nd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. New York, 2017–20. https://theleidencollection.com/artists/abraham-bloemaert/ (archived June 2020). A PDF of every version of this biography is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. Abraham Bloemaert was born in Gorinchem on Christmas Eve, 1566. His parents were Cornelis Bloemaert (ca. 1540–93), a Catholic sculptor who had fled nearby Dordrecht, and Aeltgen Willems.[1] In 1567, the family moved to ’s-Hertogenbosch, where Cornelis worked on the restoration of the interior of the St. Janskerk, which had been badly damaged during the Iconoclastic Fury of 1566. Cornelis returned to Gorinchem around 1571, but not for long; in 1576, he was appointed city architect and engineer of Utrecht. Abraham’s mother had died some time earlier, and his father had taken a second wife, Marigen Goortsdr, innkeeper of het Schilt van Bourgongen. Bloemaert probably attended the Latin school in Utrecht. He received his initial art education from his father, drawing copies of the work of the Antwerp master Frans Floris (1519/20–70). According to Karel van Mander, who describes Bloemaert’s work at length in his Schilder-boek, his subsequent training was fairly erratic.[2] His first teacher was Gerrit Splinter, a “cladder,” or dauber, and a drunk. The young Bloemaert lasted barely two weeks with him.[3] His father then sent him to Joos de Beer (active 1575–91), a former pupil of Floris. -

The Triumph of Flora

Myths of Rome 01 repaged 23/9/04 1:53 PM Page 1 1 THE TRIUMPH OF FLORA 1.1 TIEPOLO IN CALIFORNIA Let’s begin in San Francisco, at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in Lincoln Park. Through the great colonnaded court, past the Corinthian columns of the porch, we enter the gallery and go straight ahead to the huge Rodin group in the central apse that dominates the visitor’s view. Now look left. Along a sight line passing through two minor rooms, a patch of colour glows on the far wall. We walk through the Sichel Glass and the Louis Quinze furniture to investigate. The scene is some grand neo-classical park, where an avenue flanked at the Colour plate 1 entrance by heraldic sphinxes leads to a distant fountain. To the right is a marble balustrade adorned by three statues, conspicuous against the cypresses behind: a muscular young faun or satyr, carrying a lamb on his shoulder; a mature goddess with a heavy figure, who looks across at him; and an upright water-nymph in a belted tunic, carrying two urns from which no water flows. They form the static background to a riotous scene of flesh and drapery, colour and movement. Two Amorini wrestle with a dove in mid-air; four others, airborne at a lower level, are pulling a golden chariot or wheeled throne, decorated on the back with a grinning mask of Pan. On it sits a young woman wearing nothing but her sandals; she has flowers in her hair, and a ribboned garland of flowers across her thighs. -

A.P. Art History Simplified Timeline Through 1900 Note: These Are Approximate Dates

Marsha K. Russell 1 St. Andrew's Episcopal School, Austin, TX A.P. Art History Simplified Timeline through 1900 Note: These are approximate dates. Remember periods and styles overlap. Prehistory Paleolithic: up to about 10,000 BCE • Venus/Goddess of Willendorf • Lascaux Cave Paintings • Altamira Cave Paintings Neolithic in England: about 2,000 BCE • Stonehenge Mesopotamia/Near East (ignore time lapses) Sumerian: ~3500 - 2300 BCE • Standard of Ur • Ram offering stand • Bull-headed lyre • Bull holding a Vase • Ziggurats Akkadian: ~2300 - 2200 BCE • Victory Stele of Naram-Sin Neo Sumerian: ~2200 - 2000 BCE • Gudea statues Babylonian: ~1900 - 1600 BCE • Stele of Hammurabi Assyrian: ~900 - 600 BCE • Lamassu (Winged Human-Headed Bull) • Lion Hunt Bas Reliefs Egypt Predynastic: 3500 - 3000 BCE • Palette of Narmer Old Kingdom: ~3000 - 2200 BCE • Khafre • Menkaure and Khamerernebty • Seated Scribe • Ti Watching a Hippo Hunt • Prince Rahotep and his wife Nofret • Pyramid of King Djoser by Imhotep Middle Kingdom: ~2100 - 1600 BCE • Rock-cut tomb New Kingdom: ~1500 - 40 BCE (includes the Amarna Period 1355 – 1325 BCE) • Funerary Temple of Hatshepsut • Temple of Ramses II • Temple of Amen-Re at Karnak • Akhenaton • Akhenaton and His Family Marsha K. Russell 2 St. Andrew's Episcopal School, Austin, TX Aegean & Greece Minoan: ~2000 - 1500 BCE • Snake Goddess • Palace at Knossos • Dolphin Fresco • Toreador Fresco • Octopus Vase Mycenean: ~1500 - 1100 BCE • "Treasury of Atreus" with its corbelled vault • Repoussé masks • Lion Gate at Mycenae • Inlaid dagger -

INNOVATION and EXPERIMENTATION: VENETIAN RENAISSANCE and MANNERISM (Titian and Pontormo) VENETIAN RENAISSANCE

INNOVATION and EXPERIMENTATION: VENETIAN RENAISSANCE and MANNERISM (Titian and Pontormo) VENETIAN RENAISSANCE Online Links: Giovanni Bellini - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Feast of the Gods – Smarthistory The Tempest - Smarthistory Titian - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Bacchus and Ariadne – Smarthistory Titian's Bacchus and Ariadne- National Gallery Podcast Venus of Urbino - Smarthistory Giorgione - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Alfonso I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Venus of Urbino - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia MANNERISM Online Links: Introduction to Mannerism - Smarthistory Correggio's Assumption of the Virgin - Smarthistory (no video) Parmigianino's Madonna of the Long Neck – Smarthistory Benvenuto Cellini's Perseus Beheading Medusa Benvenuto Cellini - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Pontormo's Entombment - Smarthistory Giovanni Bellini and Titian. The Feast of the Gods, 1529, oil on canvas Above: Map of 16th century Venice Left: Giovanni Bellini. Self-Portrait The High Renaissance in Venice coincided with the decline of the empire and the threat that the city would lose the independent status it had enjoyed for eight hundred years. Formidable foreign powers such as the French and Spanish kings, the pope, the Holy Roman emperor, and the rulers of Milan united against Venice and formed the League of Cambrai in 1509. They took most of the Venetian territory, including the important city of Verona, but not Venice itself. By 1529, peace was restored along with most of the territory, and Venice propagated the myth of its uniqueness in having survived so great a threat. In this illustration of a scene from Ovid’s, Fasti the gods, Jupiter, Neptune, and Apollo among them, revel in a wooded pastoral setting, eating and drinking, attended by nymphs and satyrs. -

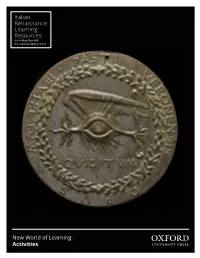

New World of Learning: Activities 1

In collaboration with the National Gallery of Art Page 1 of 8 New World of Learning: Activities 1. The Medal: INTERMEDIATE / ADVANCED The Renaissance “Calling Card” The medal was an important part of the PROCEDURE: After viewing and discussing Renaissance visual vocabulary. It allowed for images of various medals in class, divide one’s sense of self to be presented in a small the class into small groups, with each group format for distribution to friends and people given the assignment to design a medal. Have in positions of power. Rulers, intellectuals, each group choose a Renaissance individual, wealthy merchants, married women, and either real or imagined, whom they have widows are all known to have commissioned studied, read about, or discussed in this unit. medals. This activity looks at a variety of Encourage the groups to commemorate a Renaissance men and women in different range of individuals including, for example: levels of society and the kinds of medals they • A powerful aristocratic and autocratic ruler may have ordered for themselves. in control of a territory PURPOSE: to prompt students to consider • A scholar whose favorite occupation is which qualities Renaissance men and women wanted to project in images of and transcribing ancient texts reading but who is also engaged in finding themselves, and why; to prompt students to • A lady-in-waiting to Isabella d’Este, a kind of think about how such characteristics can be social secretary and personal assistant who communicated by symbolic means, helps Isabella with her clothes, reads to her at night, and keeps a list of her personal and political contacts MATERIALS: images of the medals presented in this unit (see unit images) • A wealthy merchant in a city such as Florence (Optionally, you can also consider modern autocratic ruler commemorative medals, which can be seen who is influential and powerful but not an at the websites listed under Resources, below.) Page 2 of 8 New World of Learning: Activities 1. -

National Gallery of Art OPENING EXHIBITIONS CONTINUING EXHIBITIONS

National Gallery of Art MARCH Monday, February 26 Monday, March 5 Monday, March 12 Monday, March 19 through through through through Sunday, March 4 Sunday, March 11 Sunday, March 18 Sunday, March 25 COLLECTION HIGHLIGHTS February 27-March 4 March 6-March 11 March 13-March 18 March 20-March 25 Brief gallery talks given by Education Henri Rousseau Claude Monet Sir Joshua Reynolds Pierre Puvis de Chavannes Department lecturers on a single work of art. Tropical Forest with Monkeys The Seine at Giverny Squire Musters Work Reproductions of the works discussed may be (John Hay Whitney (Chester Dale Collection) (Given in memory of (Widener Collection) purchased in the Gallery's sales shops; a Collection) West Building, Gallery 90 Governor Alvan T. Fuller by West Building, Gallery 80 written text is available without charge. West Building, Gallery 84 The Fuller Foundation, Inc.) Frances Feldman, Lecturer West Building, Gallery 59 Russell Sale, Lecturer Tuesday through Saturday 12:00p.m. William J. Williams, Lecturer Sunday 2:00 p.m. Philip Leonard, Lecturer SPECIAL TOURS February 27-March 4 March 6-March 11 March 13-March 18 March 20-March 25 One-hour thematic tours given by Education Eighteenth-Century Styles in Frederic Edwin Church Serpents and Beasts as French Painting in the 1890s Department lecturers. England and France East Building Devil's Advocates in Art West Building, Rotunda West Building, Rotunda Ground Floor Lobby West Building, Rotunda 1:00p.m. Tuesday through Saturday Eric Denker. Lecturer Sunday 2:30 p.m. Philip Leonard, Lecturer Sally Shelburne, Lecturer William J. Williams. Lecturer FILMS February 26-March 4 March 5-March 11 March 12-March 18 March 19-March 25 Free films on art and feature films related to Claes Oldenburg (Michael Islands (Albert and David Horowitz Plays Mozart Matisse, Voyages (Didier special exhibitions. -

Collected Coral and the Study of Petrified Luxury in Early Modern Antwerp

Dutch Crossing Journal of Low Countries Studies ISSN: 0309-6564 (Print) 1759-7854 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ydtc20 ‘Unusual Excrescences of Nature’: Collected Coral and the Study of Petrified Luxury in Early Modern Antwerp Marlise Rijks To cite this article: Marlise Rijks (2019) ‘Unusual Excrescences of Nature’: Collected Coral and the Study of Petrified Luxury in Early Modern Antwerp, Dutch Crossing, 43:2, 127-156, DOI: 10.1080/03096564.2017.1299931 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03096564.2017.1299931 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 15 Mar 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1005 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ydtc20 DUTCH CROSSING 2019, VOL. 43, NO. 2, 127–156 https://doi.org/10.1080/03096564.2017.1299931 ‘Unusual Excrescences of Nature’: Collected Coral and the Study of Petrified Luxury in Early Modern Antwerp Marlise Rijks Centre for the Arts in Society (LUCAS), Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Many seventeenth-century Antwerp collections contained coral, coral; collections; Antwerp; both natural and crafted. Also, coral was a pictorial motif depicted petrifaction; 17th century by Antwerp artists on mythological scenes, still lifes, gallery pic- tures, and allegories. Coral was many things at the same time: a commodity crafted into jewellery and objets d’art, a popular collectable in its natural shape, a motif for Antwerp painters, an essential commodity in the European-Indian trade network, a naturalia associated with classical mythology as well as with the Blood of Christ, and a problematic naturalia that raised ques- tions about classification, origins and natural processes. -

Procession and Return Bacchus, Poussin, and the Conquest of Ancient Territory

Procession and Return Bacchus, Poussin, and the Conquest of Ancient Territory Robert D. Meadows-Rogers The Bacchanals of Nicolas Poussin have generally the god and celebrate his mysteries and, in been construed either as archaeologically-exacting general, extol with hymns the presence of representations of ancient orgiastic frenzies or, more Dionysus, in this manner acting the pan of the usually, as syncretistic allegorical summaries of late Maenads, who, as history records, were of old Renaissance and Baroque natural philosophy. Focusing the companions of the god. He also punished specifically on the Kansas City Triumph of Bacchus, this here and there throughout all the inhabited discussion seeks to add the dimension of the political con world many men who were thought to be cerns of the patron, Cardinal Richelieu. The Cardinal of impious ... ,,. course played a crucial role in the propagandistic eleva Poussin's Triumph ofBacchus (Figure l) reflects the tion of the Bourbon monarchy as both a fecund and wise seemingly oxymoronic Bacchic frenzy for order described institution, necessary to France's growth in power and in by Diodorus and prevalent in the Orphic Hymns as well. fluence. Such concerns are posited here as directly related According to this perspective, in the course of Bacchic vic to the choice of a Bacchic theme for the Poussin tories, the impious are punished, liturgical discipline is commission. set, and the prerogatives of the revel are upheld The present author shares an interest in Poussin's use concurrently. of the antique with those who have previously commented In May 1636, the Bishop of Albi delivered this paint on the painting. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: AMALIA VAN SOLMS and THE

ABSTRACT Title of Document: AMALIA VAN SOLMS AND THE FORMATION OF THE STADHOUDER’S ART COLLECTION, 1625-1675 Virginia C. Treanor, Doctor of Philosophy, 2012 Directed By: Professor Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology This dissertation examines the role of Amalia van Solms (1602-1675), wife of Frederik Hendrik, Prince of Orange and Stadhouder of the United Provinces of the Netherlands (1584-1647), in the formation of the couple’s art collection. Amalia and Frederik Hendrik’s collection of fine and decorative arts was modeled after foreign, royal courts and they cultivated it to rival those of other great European treasure houses. While some scholars have recognized isolated instances of Amalia’s involvement with artistic projects at the Stadhouder’s court, this dissertation presents a more comprehensive account of these activities by highlighing specific examples of Amalia’s patronage and collecting practices. Through an examination of gifts of art, portraits of Amalia and her porcelain collection, this study considers the ways in which Amalia contributed to the formation of the Stadhouder’s art collection. This dissertation seeks to provide a greater knowledge not only of Amalia’s activities as a patron and collector, but also a more throrough understanding of the genesis and function of the collection as a whole, which reflected the power and glory of the House of Orange during the Dutch Golden Age. AMALIA VAN SOLMS AND THE FORMATION OF THE STADHOUDER’S ART COLLECTION, 1625-1675 By Virginia Clare Treanor Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2012 Advisory Committee: Professor Arthur K. -

Journal of Social and Humanities Sciences

JOURNAL OF SOCIAL AND HUMANITIES SCIENCES RESEARCH 2017 Vol:4 / Issue:10 pp.339-354 Economics and Administration, Tourism and Tourism Management, History, Culture, Religion, Psychology, Sociology, Fine Arts, Engineering, Architecture, Language, Literature, Educational Sciences, Pedagogy & Other Disciplines Article Arrival Date (Makale Geliş Tarihi) 11/09/2017 The Published Rel. Date (Makale Yayın Kabul Tarihi) 21/09/2017 The Published Date (Yayınlanma Tarihi 21.09.2017) OYSTER SYMBOLISM IN THE ART OF PAINTING* Assist. Prof. Dr. Defne AKDENİZ Okan University, School of Applied Disciplines, Istanbul/Turkey ABSTRACT Oysters are generally known with their legendary power as an aphrodisiac. In ancient Greek, oysters were so common that no banquet was complete without a spread of oysters and other seafood. In Roman gastronomy, oysters were a luxury dish. Romans washed oysters in vinegar and kept in jars sealed with pitch. The feminine symbolism of their shell imposes iconographic meaning to oysters. The presence of oysters in paintings generally intensifies the eroticism, physical love and chastity in the atmosphere. Their erotic affect appears in Italian, French, English and especially Dutch genre paintings of the 17th and 18th centuries. This study examines oysters within its figurative context in genre and still life paintings. In this study, starting with an introductory history of the oysters, and their use in ancient civilizations, oysters are examined through the paintings of Sandro Botticelli’s ‘The Birth of Venus’, Hendrik van Balen II’s ‘The Feast of the Gods’, Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder’s ‘The Feast of Acheloüs’, Frans Francken II’s ‘Supper at the House of Burgomaster Rockox', Jan Steen’s ‘A Girl Eating Oysters’, and Pieter Claesz’s ‘Still Life with Turkey Pie’. -

The Feast of the Gods

60 review. Number 327, October 2020 I THE ART NEWSPAPER BOOKS Reviews David Alan Brown Giovanni Bellini. The Last Works Skira, 400pp, €75 (hb) Julius von Schlosser thought the most highly desirable art-history book would be a monograph based on a single work of art, emphasising the “island” nature of a masterpiece. David Alan Brown mag- nificent study of Bellini’sThe Feast of the Gods (1514) – the result of a long acquaint- ance with the painting during his more than four decades at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC – is just such a book. Despite a title that promises to look at all the late works, which he does in detail, the book continually revolves around The Feast of the Gods, and presents absolute novelties in interpretation that Computer simulation of Bellini’s The Feast of the Gods (1514) without the unsympathetic interventions by Dosso Dossi and Titian (left), and the original painting in Washington, DC will contribute to our understanding of Venetian Renaissance painting forever. Brown introduces his study with the observation that Bellini, who enjoyed longevity, had the luck or misfortune to A spotlight on ‘The Feast of the Gods’ live on into the 16th century. He implies that The Feast is a 15th-century painting More than 40 years’ study of Bellini has gone into this outstanding book. By despite its date. Brown accepts Pietro Jaynie Anderson Bembo’s characterisation of Bellini’s creative practice, as defined for Isabella Equicola, then an analysis of the classi- non-invasive multispectral scanning. painting. The new computer simulation appears to be too tight to allow for the d’Este, Marchioness of Mantua, when cal texts that reveal how Bellini departed (There is a detailed appendix explaining of The Feast of the Gods as it may have left recognition of individual hands. -

Mantegna's Mars and Venus

Abstract Title of Document: Mantegna’s Mars and Venus: The Pursuit of Pictorial Eloquence Steven J. Cody, Master of Arts, 2009 Directed By: Professor Meredith J. Gill, Department of Art History and Archeology This paper examines the pictorial composition of Andrea Mantegna’s Mars and Venus and its relation to the culture of letters and antiquarianism present in the studiolo of Isabella d’Este Gonzaga. By analyzing Mantegna’s use of contrapposto, a visual motif stemming from the rhetorical figure of “antithesis,” I argue that the artist formally engages Classical rhetoric and the principles of Leon Battista Alberti’s De Pictura. Mantegna’s dialogue with Albertian and rhetorical theory visually frames the narrative of Mars and Venus in a way that ultimately frames the viewer’s understanding of Isabella’s character as a patron of the arts. But it also has ramifications for how the viewer understands Mantegna’s activities as a painter. By focusing my investigation on the significance of pictorial form and Mantegna’s process of imitation, I look to emphasize the intellectual nuances of Isabella’s approach to image making and to link Mantegna’s textual knowledge to his visual recuperation of Classical art. MANTEGNA’S MARS AND VENUS: THE PURSUIT OF PICTORIAL ELOQUENCE By Steven J. Cody Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2009 Advisory Committee: Professor Meredith J. Gill, Chair Professor Anthony Colantuono Professor Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. © Copyright by Steven Joseph Cody 2009 Disclaimer The thesis document that follows has had referenced material removed in respect for the owner’s copyright.