ABSTRACT Title of Document: AMALIA VAN SOLMS and THE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tracing the Origin of Blue and White Chinese Porcelain Ordered for the Portuguese Market During the Ming Dynasty Using INAA

Journal of Archaeological Science 40 (2013) 3046e3057 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/jas Tracing the origin of blue and white Chinese Porcelain ordered for the Portuguese market during the Ming dynasty using INAA M. Isabel Dias a,*, M. Isabel Prudêncio a, M.A. Pinto De Matos b, A. Luisa Rodrigues a a Campus Tecnológico e Nuclear/Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, EN 10 (Km 139,7), 2686-953 Sacavém, Portugal b Museu Nacional do Azulejo, Rua da Madre de Deus no 4, 1900-312 Lisboa, Portugal article info abstract Article history: The existing documentary history of Chinese porcelain ordered for the Portuguese market (mainly Ming Received 21 March 2012 dynasty.) is reasonably advanced; nevertheless detailed laboratory analyses able to reveal new aspects Received in revised form like the number and/or diversity of producing centers involved in the trade with Portugal are lacking. 26 February 2013 In this work, the chemical characterization of porcelain fragments collected during recent archaeo- Accepted 3 March 2013 logical excavations from Portugal (Lisbon and Coimbra) was done for provenance issues: identification/ differentiation of Chinese porcelain kilns used. Chemical analysis was performed by instrumental Keywords: neutron activation analysis (INAA) using the Portuguese Research Reactor. Core samples were taken from Ancient Chinese porcelain for Portuguese market the ceramic body avoiding contamination form the surface layers constituents. The results obtained so INAA far point to: (1) the existence of three main chemical-based clusters; and (2) a general attribution of the Chemical composition porcelains studied to southern China kilns; (3) a few samples are specifically attributed to Jingdezhen Ming dynasty and Zhangzhou kiln sites. -

Sztuki Piękne)

Sebastian Borowicz Rozdział VII W stronę realizmu – wiek XVII (sztuki piękne) „Nikt bardziej nie upodabnia się do szaleńca niż pijany”1079. „Mistrzami malarstwa są ci, którzy najbardziej zbliżają się do życia”1080. Wizualna sekcja starości Wiek XVII to czas rozkwitu nowej, realistycznej sztuki, opartej już nie tyle na perspektywie albertiańskiej, ile kepleriańskiej1081; to również okres malarskiej „sekcji” starości. Nigdy wcześniej i nigdy później w historii europejskiego malarstwa, wyobrażenia starych kobiet nie były tak liczne i tak różnicowane: od portretu realistycznego1082 1079 „NIL. SIMILIVS. INSANO. QVAM. EBRIVS” – inskrypcja umieszczona na kartuszu, w górnej części obrazu Jacoba Jordaensa Król pije, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wiedeń. 1080 Gerbrand Bredero (1585–1618), poeta niderlandzki. Cyt. za: W. Łysiak, Malarstwo białego człowieka, t. 4, Warszawa 2010, s. 353 (tłum. nieco zmienione). 1081 S. Alpers, The Art of Describing – Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century, Chicago 1993; J. Friday, Photography and the Representation of Vision, „The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism” 59:4 (2001), s. 351–362. 1082 Np. barokowy portret trumienny. Zob. także: Rembrandt, Modląca się staruszka lub Matka malarza (1630), Residenzgalerie, Salzburg; Abraham Bloemaert, Głowa starej kobiety (1632), kolekcja prywatna; Michiel Sweerts, Głowa starej kobiety (1654), J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Monogramista IS, Stara kobieta (1651), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wiedeń. 314 Sebastian Borowicz po wyobrażenia alegoryczne1083, postacie biblijne1084, mitologiczne1085 czy sceny rodzajowe1086; od obrazów o charakterze historycznodokumentacyjnym po wyobrażenia należące do sfery historii idei1087, wpisujące się zarówno w pozy tywne1088, jak i negatywne klisze kulturowe; począwszy od Prorokini Anny Rembrandta, przez portrety ubogich staruszek1089, nobliwe portrety zamoż nych, starych kobiet1090, obrazy kobiet zanurzonych w lekturze filozoficznej1091 1083 Bernardo Strozzi, Stara kobieta przed lustrem lub Stara zalotnica (1615), Музей изобразительных искусств им. -

1/110 Allemagne (Indicatif De Pays +49) Communication Du 5.V

Allemagne (indicatif de pays +49) Communication du 5.V.2020: La Bundesnetzagentur (BNetzA), l'Agence fédérale des réseaux pour l'électricité, le gaz, les télécommunications, la poste et les chemins de fer, Mayence, annonce le plan national de numérotage pour l'Allemagne: Présentation du plan national de numérotage E.164 pour l'indicatif de pays +49 (Allemagne): a) Aperçu général: Longueur minimale du numéro (indicatif de pays non compris): 3 chiffres Longueur maximale du numéro (indicatif de pays non compris): 13 chiffres (Exceptions: IVPN (NDC 181): 14 chiffres Services de radiomessagerie (NDC 168, 169): 14 chiffres) b) Plan de numérotage national détaillé: (1) (2) (3) (4) NDC (indicatif Longueur du numéro N(S)N national de destination) ou Utilisation du numéro E.164 Informations supplémentaires premiers chiffres du Longueur Longueur N(S)N (numéro maximale minimale national significatif) 115 3 3 Numéro du service public de l'Administration allemande 1160 6 6 Services à valeur sociale (numéro européen harmonisé) 1161 6 6 Services à valeur sociale (numéro européen harmonisé) 137 10 10 Services de trafic de masse 15020 11 11 Services mobiles (M2M Interactive digital media GmbH uniquement) 15050 11 11 Services mobiles NAKA AG 15080 11 11 Services mobiles Easy World Call GmbH 1511 11 11 Services mobiles Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1512 11 11 Services mobiles Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1514 11 11 Services mobiles Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1515 11 11 Services mobiles Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1516 11 11 Services mobiles Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1517 -

Scahier 74 Classicisme: Vredestempel, Prinsenhof, Haarlem

74 JAARGANG 23 n SEPTEMBER 2008 ClassicismeSC74.indd 2-3 14-9-2008 18:28:18 Vr e d e s ahier tempel PDF-versie Haarlem jaargang 23 1648 nummer 74 n september 2008 Classicisme verklaard aan de SCahier is sinds septem- ber 1985 een ongeregeld hand van een fietsenhok verschijnend schrift met essays, achtergronden, In 1648 werd in Haarlem op het Prinsenhof meningen en feiten over een Vredestempel gebouwd in een voor die tijd architectuur. Het is bedoeld uiterst moderne bouwstijl: het classicisme. Zo'n om de relaties van Ar- Vredestempel veertig jaar geleden werd dit vergeten prieeltje nog chitext op de hoogte te Sinds 1648 staat op het Haarlemse gebruikt als fietsenhok. houden over de fondslijst, Prinsenhof een ‘tempeltje’ gewijd Dit SCahier beschrijft uitvoerig de achtergronden de architectuurreizen en aan de Vrede van Munster. De van dit kleine bouwkundige sieraad. En passant Architectuurradio. achtergronden van een classicistisch wordt zo geschetst wat classicisme is en hoe het unicum. in de Republiek der Nederlanden ingang vond. Uitgeverij Architext Dat dit verhaal een sterk Haarlems karakter Klein Heiligland 91 Eerder verschenen: draagt, is niet toevallig: Haarlemmers speelden 2011 EE Haarlem SCahier 73 PDF over Retranchement (22 pagina’s), een vooraanstaande rol bij de introductie van e-post: [email protected] te importeren via www.architext.nl. de beginselen van de klassieke oudheid in het www.architext.nl bouwen. eindredactie: Ids Haagsma Inhoud: vormgeving: de IJsgarage s Haarlem Rob van Westreenen De tijd – pagina 5 © 2008 s Architext De plek – pagina 6 De maker (1) – pagina 11 De stijl – pagina 17 De Maker (2) – pagina 23 Het binnen – pagina 28 Rechts: de Vredestempel als fietsenhok, in de vorige jaren zestig. -

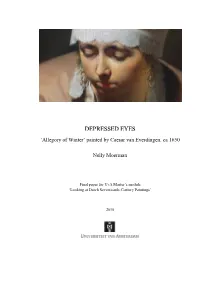

Depressed Eyes

D E P R E S S E D E Y E S ‘ Allegory of Winter’ painted by Caesar van Everdingen, c a 1 6 5 0 Nelly Moerman Final paper for UvA Master’s module ‘Looking at Dutch Seventeenth - Century Paintings’ 2010 D EPRESSED EYES || Nelly Moerman - 2 CONTENTS page 1. Introduction 3 2. ‘Allegory o f Winter’ by Caesar van Everdingen, c. 1650 3 3. ‘Principael’ or copy 5 4. Caesar van Everdingen (1616/17 - 1678), his life and work 7 5. Allegorical representations of winter 10 6. What is the meaning of the painting? 11 7. ‘Covering’ in a psychological se nse 12 8. Look - alike of Lady Winter 12 9. Arguments for the grief and sorrow theory 14 10. The Venus and Adonis paintings 15 11. Chronological order 16 12. Conclusion 17 13. Summary 17 Appendix I Bibliography 18 Appendix II List of illustrations 20 A ppen dix III Illustrations 22 Note: With thanks to the photographic services of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam for supplying a digital reproduction. Professional translation assistance was given by Janey Tucker (Diesse, CH). ISBN/EAN: 978 - 90 - 805290 - 6 - 9 © Copyright N. Moerman 2010 Information: Nelly Moerman Doude van Troostwijkstraat 54 1391 ET Abcoude The Netherlands E - mail: [email protected] D EPRESSED EYES || Nelly Moerman - 3 1. Introduction When visiting the Rijksmuseum, it seems that all that tourists w ant to see is Rembrandt’s ‘ Night W atch ’. However, before arriving at the right spot, they pass a painting which makes nearly everybody stop and look. What attracts their attention is a beautiful but mysterious lady with her eyes cast down. -

1/98 Germany (Country Code +49) Communication of 5.V.2020: The

Germany (country code +49) Communication of 5.V.2020: The Bundesnetzagentur (BNetzA), the Federal Network Agency for Electricity, Gas, Telecommunications, Post and Railway, Mainz, announces the National Numbering Plan for Germany: Presentation of E.164 National Numbering Plan for country code +49 (Germany): a) General Survey: Minimum number length (excluding country code): 3 digits Maximum number length (excluding country code): 13 digits (Exceptions: IVPN (NDC 181): 14 digits Paging Services (NDC 168, 169): 14 digits) b) Detailed National Numbering Plan: (1) (2) (3) (4) NDC – National N(S)N Number Length Destination Code or leading digits of Maximum Minimum Usage of E.164 number Additional Information N(S)N – National Length Length Significant Number 115 3 3 Public Service Number for German administration 1160 6 6 Harmonised European Services of Social Value 1161 6 6 Harmonised European Services of Social Value 137 10 10 Mass-traffic services 15020 11 11 Mobile services (M2M only) Interactive digital media GmbH 15050 11 11 Mobile services NAKA AG 15080 11 11 Mobile services Easy World Call GmbH 1511 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1512 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1514 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1515 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1516 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1517 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1520 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone GmbH 1521 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone GmbH / MVNO Lycamobile Germany 1522 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone -

Simon Thurley, ‘Kensington Palace: an Incident in Anglo-Dutch Architectural Collaboration?’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Simon Thurley, ‘Kensington Palace: an incident in Anglo-Dutch architectural collaboration?’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XVII, 2009, pp. 1–18 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2009 KENSINGTON PALACE: AN INCIDENT IN ANGLO-DUTCH ARCHITECTURAL COLLABORATION? SIMON THURLEY illiam III was brought up in what is often The second was after the death of Charles II in Wtermed the ‘Golden Age’ of Dutch culture, in when William and Mary became next in line to the a country whose intellectual and artistic singularity throne of England after James II. In this period and creativity were recognised across Europe. William’s court, such as it was, was swelled by He came, as King, to a country that Voltaire saw as English visitors and his palaces were enlarged and having made, since , ‘greater progress in all the made more magnificent, both to entertain them, and arts than in all preceding ages’, and having the to reflect his increased status. These bursts of cultural influence to create in Europe the ‘Age of the architectural activity were triggered by the practical English’. The marriage of the two cultures in the requirements of a prince, rather than being the result person of King William was surely to hold great of a love of building and architectural display such as things for the state of English architecture. Yet, in that which drove his grandparents. In Jacob van reality, the English king who spent more on building der Does wrote of William’s grandfather, Frederik than any other in the seventeenth century led court Hendrik, that he was ‘possessed by such a passion architecture into a cul-de-sac. -

This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached Copy Is Furnished to the Author for Internal Non-Commerci

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Advances in Water Resources 32 (2009) 129–146 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Advances in Water Resources journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/advwatres Assessing the impact of land use change on hydrology by ensemble modeling (LUCHEM). I: Model intercomparison with current land use L. Breuer a,*, J.A. Huisman b, P. Willems c, H. Bormann d, A. Bronstert e, B.F.W. Croke f, H.-G. Frede a, T. Gräff e, L. Hubrechts g, A.J. Jakeman f, G. Kite h, J. Lanini i, G. Leavesley j, D.P. Lettenmaier i, G. Lindström k, J. Seibert l, M. Sivapalan m,1, N.R. Viney n a Institute for Landscape Ecology and Resources Management, Justus-Liebig-University Giessen, Heinrich-Buff-Ring 26, 35392 Giessen, Germany b ICG-4 Agrosphere, Forschungszenrum Jülich, Germany c Hydraulics Laboratory, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium -

Empire of Tea

Empire of Tea Empire of Tea The Asian Leaf that Conquered the Wor ld Markman Ellis, Richard Coulton, Matthew Mauger reaktion books For Ceri, Bey, Chelle Published by Reaktion Books Ltd 33 Great Sutton Street London ec1v 0dx, uk www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2015 Copyright © Markman Ellis, Richard Coulton, Matthew Mauger 2015 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 978 1 78023 440 3 Contents Introduction 7 one: Early European Encounters with Tea 14 two: Establishing the Taste for Tea in Britain 31 three: The Tea Trade with China 53 four: The Elevation of Tea 73 five: The Natural Philosophy of Tea 93 six: The Market for Tea in Britain 115 seven: The British Way of Tea 139 eight: Smuggling and Taxation 161 nine: The Democratization of Tea Drinking 179 ten: Tea in the Politics of Empire 202 eleven: The National Drink of Victorian Britain 221 twelve: Twentieth-century Tea 247 Epilogue: Global Tea 267 References 277 Bibliography 307 Acknowledgements 315 Photo Acknowledgements 317 Index 319 ‘A Sort of Tea from China’, c. 1700, a material survival of Britain’s encounter with tea in the late seventeenth century. e specimen was acquired by James Cuninghame, a physician and ship’s surgeon who visited Amoy (Xiamen) in 1698–9 and Chusan (Zhoushan) in 1700–1703. -

2000 Jaargang 99

Robert Hook Hollandd ean : Dutch influenc architecturs hi n eo e Alison Stoesser-Johnston The use of these publications by English architects and arti- Introductie)!! sans and the design of Wollaton Hall were not based on any Dutch classicism was a recent arrival in England when first-hand personal impressio f classicisno Italymn i . Thid ha s Robert Hooke made his first architectural designs in the late emergence th waio t r fo t f Inigeo o Jone s architectsa visis Hi . t 1660s. 'e constructioPrioth o t r f Hugo n h May's Eltham to Italy in 1613-'14 in the entourage of Thomas Howard, 2nd Lodg 1663-'64n i e e firsth , t exampl f Dutceo h classicisn mi Earl of Arundel, his close interest in Roman antiquities and England, classical elements straight from Italy and via Flan- intimate knowledge of Palladio's drawings are most ders had been used in English architecture for nearly a hund- dramatically exemplifie Banquetins hi n di g Hous f 1619-22eo . red years. Initially these had been mainly of a decorative na- Not only, however, has Jones here used Palladian "vocabulary" ture but vvith the construction of Inigo Jones' Banqueting 7 but hè has combined it with the application of Scamozzian House (1619-'21) there was a dramatic change in the way orders, the Composite being superimposed on the lonic. This classicism was adapted to English architecture. Jones drew combination of Palladian elements with Scamozzian also on the examples of Palladio and Scamozzi in his architecture influence beginninge th d f Dutcso h classicism.8 Jones' design using both Palladio's treatise, / quattro libri, personal know- was not only a major innovation in England but it also inspired ledge of his architecture and, in the case of Scamozzi, per- Jaco n Campe s va bfirs hi tn i narchitectura l commission i n sonal contact e applieH . -

Light and Sight in Ter Brugghen's Man Writing by Candlelight

Volume 9, Issue 1 (Winter 2017) Light and Sight in ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight Susan Donahue Kuretsky [email protected] Recommended Citation: Susan Donahue Kuretsky, “Light and Sight in ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight,” JHNA 9:1 (Winter 2017) DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.4 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/light-sight-ter-brugghens-man-writing-by-candlelight/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 7:2 (Summer 2015) 1 LIGHT AND SIGHT IN TER BRUGGHEN’S MAN WRITING BY CANDLELIGHT Susan Donahue Kuretsky Ter Brugghen’s Man Writing by Candlelight is commonly seen as a vanitas tronie of an old man with a flickering candle. Reconsideration of the figure’s age and activity raises another possibility, for the image’s pointed connection between light and sight and the fact that the figure has just signed the artist’s signature and is now completing the date suggests that ter Brugghen—like others who elevated the role of the artist in his period—was more interested in conveying the enduring aliveness of the artistic process and its outcome than in reminding the viewer about the transience of life. DOI:10.5092/jhna.2017.9.1.4 Fig. 1 Hendrick ter Brugghen, Man Writing by Candlelight, ca. -

The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 2Nd Ed

Abraham Bloemaert (Gorinchem 1566 – 1651 Utrecht) How to cite Bakker, Piet. “Abraham Bloemaert” (2017). Revised by Piet Bakker (2019). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 2nd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. New York, 2017–20. https://theleidencollection.com/artists/abraham-bloemaert/ (archived June 2020). A PDF of every version of this biography is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. Abraham Bloemaert was born in Gorinchem on Christmas Eve, 1566. His parents were Cornelis Bloemaert (ca. 1540–93), a Catholic sculptor who had fled nearby Dordrecht, and Aeltgen Willems.[1] In 1567, the family moved to ’s-Hertogenbosch, where Cornelis worked on the restoration of the interior of the St. Janskerk, which had been badly damaged during the Iconoclastic Fury of 1566. Cornelis returned to Gorinchem around 1571, but not for long; in 1576, he was appointed city architect and engineer of Utrecht. Abraham’s mother had died some time earlier, and his father had taken a second wife, Marigen Goortsdr, innkeeper of het Schilt van Bourgongen. Bloemaert probably attended the Latin school in Utrecht. He received his initial art education from his father, drawing copies of the work of the Antwerp master Frans Floris (1519/20–70). According to Karel van Mander, who describes Bloemaert’s work at length in his Schilder-boek, his subsequent training was fairly erratic.[2] His first teacher was Gerrit Splinter, a “cladder,” or dauber, and a drunk. The young Bloemaert lasted barely two weeks with him.[3] His father then sent him to Joos de Beer (active 1575–91), a former pupil of Floris.