BAG Newsletter 34

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SIA Newsletter (SIAN)

Volume 34 Fall 2005 Number 4 NATIONAL HERITAGE AREAS Current Trends Shaping the Future of America’s Industrial Sites ver the past 20 years the national heritage area eral conservation; it was not established as a National Park movement has gained momentum and unit, but as a heritage area—a large living landscape—where embraced industrial history. National heritage the federal government offered assistance to local organizers. O areas receive federal funding and technical This idea opened the door to the conservation of other large- support from the U. S. National Park Service scale waterways, canal systems, and associated industrial sites (NPS) but emphasize a partnership of local private and that previously were seen as just too big to handle as tradi- public institutions that share common themes and actually tional parks. Since then, 27 national heritage areas have been own or manage most of the properties within the heritage established and 36 bills are currently pending in Congress to area. For example, Detroit’s Motorcities National Heritage establish new heritage areas. The majority of existing nation- Area brings together local organizations around the theme al heritage areas are organized around the themes of industri- of automobile history, Dayton’s National Aviation Heritage al and transportation history, but in recent years themes of Area around aviation history, and Pittsburgh’s Rivers of maritime, Civil War battlefield, and agricultural history have Steel Heritage Area around steel heritage. Many heritage been used. areas are located along former canals or waterways and Today, the increasing interest in establishing new heritage include the Augusta Canal (GA), Cane River (LA), areas has challenged both Congress and the NPS to develop Delaware & Lehigh Canal (PA), Illinois & Michigan Canal a legislative framework to set standards for evaluation and (IL), Ohio & Erie Canal (IN), and Schuylkill River (PA). -

4. Ibid, P. 190. 5. Spadework, 1953, P. 12. 7. Presidential Address to the Society of Antiquaries, Antiquaries Journal, 1975, Vo

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. A Hundred and Fifty Years of Archaeology, p. 104. 2. Allen v Thorn Electrical Industries, Ltd. 1907. 3. My First Hundred Years, 1963, p. 189. 4. Ibid, p. 190. 5. Spadework, 1953, p. 12. 6. Archaeology in the Field, 1953, p. 8. 7. Presidential Address to the Society of Antiquaries, Antiquaries journal, 1975, vol. LV, partl, p. 7. 8. Antiquaries journal, 'Excavations at Winchester, 1969. Eighth Interim Report', p. 227. 9. Ibid, pp. 277-8. 10. Ibid, p.278. 11. Antiquaries journal, vol. LV, partl, 1975, p. 5. 12. Ibid, p. 6. 13. On the characteristics of the professions, near-professions and would-be professions, see Kenneth Hudson, The Jargon of the Professions, 1978, pp. 7-12. 14. Myres, op. cit., p. 6. 15. Myres, op. cit., pp. 7-8. 16. Ibid, p. 7. CHAPTER 1 1. Somersetshire Archaeological and Natural History Society: Proceedings during the Years 1849-50, vol. 1, 1851. 2. On this, see Stuart Piggott, 'County Archaeological Societies', Antiquity, June 1968. 3. Somersetshire Archaeological and Natural History Society. Proceedings during the Years 1948-9, vol. XCIV, 1950, p. 28. 4. Year of the Society's foundation. 5. Vol. X, 1930, p. 393. 6. Vol. I, 1921, p. 76. 7. Vol. II, 1922, p. 391. 8. Vol. II, 1922, pp. 390-1. 9. Vol. II, 1922, p. 68. 186 Notes 10. Vol. II, 1922, p. 69. 11. Vol. XIII, 1933, p. 173. 12. Vol. II, 1922, p. 269. 13. The well-known journal on early archaeology, Mat&iaux pour l'histoire de /'hom me. 14. -

Download .PDF

Yale university press Fall/Winter 2020 Marcus Carey Batchelor Bate Under the Red White A Little History of The Art of Solitude Radical Wordsworth and Blue Poetry Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover 978-0-300-25093-0 978-0-300-16964-5 978-0-300-22890-8 978-0-300-23222-6 $23.00 $35.00 $26.00 $25.00 Unwin/Tipling Delbanco Leibovitz Campbell Flights of Passage Why Writing Matters Stan Lee Year of Peril Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover 978-0-300-24744-2 978-0-300-24597-4 978-0-300-23034-5 978-0-300-23378-0 $40.00 $26.00 $26.00 $30.00 Van Engen Reynolds Taylor Musonius Rufus City on a Hill Allah Sons of the Waves That One Should Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover Disdain Hardships 978-0-300-22975-2 978-0-300-24658-2 978-0-300-24571-4 Hardcover $30.00 $30.00 $30.00 978-0-300-22603-4 $22.00 RECENT GENERAL INTEREST HIGHLIGHTS Yale university press FALL/WINTER 2020 GENERAL INTEREST 01 JEWISH LIVES® 24 MARGELLOS WORLD REPUBLIC OF LETTERS 26 SCHOLARLY AND ACADEMIC 56 PAPERBACK REPRINTS 73 ART + ARCHITECTURE A 1 front cover illustration: Via Roma, Genoa, Italy, ca. 1895. From Stories for the Years, page 28 “This book is superb, utterly FROM TAKE ARMS AGAINST A SEA OF TROUBLES: convincing, and absolutely invigorating. Bloom’s final argument with mortality What you read and how deeply you read matters almost as much as how you ultimately has a rejuvenating love, work, exercise, vote, practice charity, strive for social justice, cultivate effect upon the reader, kindness and courtesy, worship if you are capable of worship. -

2000 Midwest Archaeological Conference Program

AflT2- Program and Abstracts Joint Midwest Archaeological / Plains Anthropological Conference St. Paul , Minnesota th th Novem ber 9 - 12 , 2000 A.D. Spansored b_y The Minnesota office of the State Archaeologist REP ::'onferenc MAC 2000 JOINT CONFERENCE , SAINT PAUL, MINNESOTA MIDWEST eArchaeological I PLAINS eAnthropological The Joint Midwest Archaeological / Plains Anthropalogical Conference Planning Committee: • Mark Dudzik, Joint Conference chair, office of the State Archaeologist • Robert douse, ~ Midwest Program Chair, Minnesota Historical Societ_y • Scott Anfinson, Plains Program Chair, State Historic Preservation Office • Bruce Koenen, Conference Registration, Office of the State Archaeologist • Kim Breake9, Program Coordinator, Hemisphere Field Services • Pat E:merson, Volunteer Coordinator, Department of Natural Resources ~ tr TABLE OF CONTENTS MtK. Acknowledgments . .. • . ...2~..2 General Information . • . .3 Schedule At-a-Glance . .. .. • . .. • . .... .4 Program . ........ .. .. .. .... .. 5 Friday AM . .. ... ... .. .... .5 Friday PM .. • . .. .. , . • . ... .. 9 Saturday AM .. .. ..... 14 Saturday PM .. .. ... ... .. 19 Sunday A..l\1 . .. • . .. ... • . • . .24 Symposia Abstracts . .. .... .. .. ..27 Paper Abstracts . .. ... • . ... ..31 JOINT CONFERENCE • SAINT PAUL, MINNESOTA The Joint Conference logo is based on a painting by Edward K Thomas ("Fort Snelling", 1850; see cover: courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society). The perspective is westward from the bluffs above the historic Sibley House, to Fort Snelling, -

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME Tuesday, July 7 Panel Session 2: 09.30-11:00 / Panel Session 3: 11:30-13:00

15th International Conference of the European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists 6 -10 July 2015, Université Paris Ouest Nanterre la Défense Organisers and acknowledgements Map of Campus EurASEAA15 Conference main organiser: Bérénice Bellina-Pryce (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifi que, UMR 7055 “Préhistoire et Technologie”) EurASEAA15 Scientifi c Committee: Bérénice Bellina-Pryce (Chair – CNRS, UMR 7055 “PréTech”), Véronique Degroot (EFEO), Jean- MAE Christophe Galipaud (Paloc, MNHN/IRD), Agustijanto Indrajaya (Pusat Arkeologi Nasional, Indonesian EurASEAA15 National Archaeology Center), Nam Kim (University Wisconsin-Madison), Helen Anne Lewis (University College Dublin), Thomas Oliver Pryce (CNRS, UMR7055 “PréTech”), François Sémah P (MNHN), Rasmi Shoocongdej (Silpakorn University) EurASEAA15 Organising Committee: EurASEAA15 Bérénice Bellina-Pryce (CNRS, UMR 7055 “Préhistoire et Technologie”), Thomas Oliver Pryce (CNRS, Bâtiment B t t UMR7055 “PréTech”), Pierre Baty (Inrap), Claudine Bautze-Picron (CNRS, UMR7528 “Mondes iranien e e n n n n i i et indien”),Vincenzo Celiberti (Centre Européen de Recherche Préhistorique de Tautavel),Véronique s s Degroot (EFEO), Aude Favereau (MNHM), Jean-Christophe Galipaud (Paloc, MNHN/IRD), Laurence Library de Quinty (USR 3225, MAE), Isabelle Rivoal (CNRS, LESC, USR 3225), François Sémah (MNHN), Isabelle Sidéra (CNRS, UMR 7055 “Prétech”) Restaurant Conference administrators: CROUS NomadIT: Eli Bugler, Darren Edale, James Howard, Rohan Jackson, Triinu Mets, Elaine Morley Exhibitors and -

Chapter 4 the Hoabinhian of Southeast Asia and Its Relationship

Chapter 4 The Hoabinhian of Southeast Asia and its Relationship to Regional Pleistocene Lithic Technologies Ben Marwick This chapter has been peer-reviewed and published in: Robinson, Erick, Sellet, Frederic (Eds.) 2018. Lithic Technological Organization and Paleoenvironmental Change Global and Diachronic Perspectives. Springer International Publishing. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-64407-3 Abstract The Hoabinhian is a distinctive Pleistocene stone artefact technology of mainland and island Southeast Asia. Its relationships to key patterns of technological change both at a global scale and in adjacent regions such as East Asia, South Asia and Australia are currently poorly understood. These key patterns are important indicators of evolutionary and demographic change in human prehistory so our understanding of the Hoabinhian may be substantially enhanced by examining these relationships. In this paper I present new evidence of ancient Hoabinhian technology from Northwest Thailand and examine connections between Hoabinhian technology and the innovation of other important Pleistocene technological processes such as radial core geometry. I present some claims about the evolutionary significance of the Hoabinhian and recommend future research priorities. Introduction The Hoabinhian represents a certain way of making stone artifacts, especially sumatraliths, during the late Pleistocene and early Holocene in island and mainland Southeast Asia. Although it has been a widely accepted and used concept in the region for several decades, its relationships to key patterns of technological and paleoenvironmental change both at a global scale and in adjacent regions such as East Asia, South Asia and Australia are currently poorly understood. What makes these relationships especially intriguing is that the geographical locations of Hoabinhian assemblages are at strategic points on the arc of dispersal from Africa to Australia. -

3D-Documentation Technologies for Use in Industrial Archaeology Applications

3D-DOCUMENTATION TECHNOLOGIES FOR USE IN INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY APPLICATIONS A. Gruenkemeier a a Bochum University of Applied Sciences, Department of Surveying and Geomatics – [email protected] Commission WG V/2 – Cultural Heritage Documentation KEY WORDS: Application, Archaeology, Cultural heritage, Fusion, Photogrammetry, Terrestrial, Three-dimensional, TLS ABSTRACT: Industrial archaeology deals with questions of industrial culture and preservation of industrial monuments. The concept was introduced in 1955 in England, after the Swiss engineer Conrad Matschoss had expanded the history of technology to industrial monuments in 1932. The objective purpose of industrial archaeology is the preservation and documentation of the industrial-cultural heritage of international importance – a task which is mostly to be fulfilled in a race against time and hence, needs efficient and fast technologies for data capturing. Prior to an (accidental) destruction of industrial-cultural objects a correct geometrical and/or visual documentation must be reached using new technologies from the field of data capture, management and use of space-related information. This paper discusses interests in and problems of industrial archaeology, presents concepts for an integrated use of actual capturing techniques and shows typical applications. KURZFASSUNG: Die wissenschaftliche Disziplin, die sich mit Fragen der Industriekultur und Industriedenkmalpflege beschäftigt, bezeichnet man international als Industrial Archaeology (Industriearchäologie). Der Begriff wurde 1955 in England geprägt, nachdem 1932 der Schweizer Ingenieur Conrad Matschoss Technikgeschichte auch auf die Industriedenkmäler ausgedehnt hatte. Objekte der Industriearchäologie sind alle jene ober- und unterirdischen Bauten, die seit Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts erbaut worden sind. Die Dokumentation dieser international bedeutenden Zeit ist wichtig, aber häufig aufgrund der schnellen Abrissarbeiten nur schwer zu realisieren. -

Winter 2020 Contents

Yale Yale Autumn & Winter 2020 Autumn & Yale AUTUMN & WINTER 2020 Contents General Interest Highlights | Hardback 1–21 General Interest Highlights | Paperback 22–28 Art 2, 4, 26, 29–60, 67 fashion & textile 30, 34, 53 architecture 32, 47, 48, 50, 59 design & decorative 29, 31, 33, 35, 48–51, 58, 59 modern & contemporary 37, 40–42, 45, 46, 51–54, 59, 60 18th & 19th century 36, 37, 43, 54, 56 15th, 16 th & 17th century 40, 44, 45, 54, 56, 57 ancient & antiquity 48, 49, 57–59 collections & theory 44, 46, 58, 59, 60 Mathematics, Science & Medicine 21, 22, 63, 72 Business & Economics 7, 11, 12, 61 History 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 14, 15, 20–28, 62–64, 74–76 Biography & Memoir 2, 4, 5, 9, 16, 17, 23, 26, 47, 65, 75 Philosophy, Theology & Jewish Studies 9, 13, 65–68 Film, Performing Arts, Literary Studies 8, 13, 16, 17, 24–27, 52, 65, 69–71 International Affairs & Political Science 3, 10, 18, 19, 28, 61, 62, 64 American Studies 28, 74–76 Psychology, Social & Environmental Science 16, 22, 60, 62, 63, 73, 76 Picture Credits & Index 77–79 Sales Contacts 80 Ordering Information 81 Rights, Inspection Copy, Review Copy Information 81 Yale University Press YaleBooks 47 Bedford Square @yalebooks London WC1B 3DP tel 020 7079 4900 yalebooksblog.co.uk general email [email protected] www.yalebooks.co.uk A thrilling history of MI9 – the WWII organisation that engineered the escape of Allied forces from behind enemy lines MI9 A History of The Secret Service for Escape and Evasion in World War Two Helen Fry Helen Fry is a specialist in the When Allied fighters were trapped behind enemy lines, one branch of history of British Intelligence. -

SIA Newsletter, Volume 43, Number 2

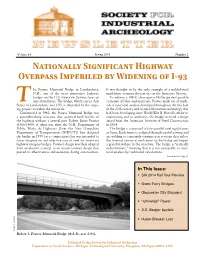

Volume 43 Spring 2014 Number 2 Nationally Significant Highway Overpass Imperiled by Widening of I-93 he Prowse Memorial Bridge in Londonderry, It was thought to be the only example of a welded-steel N.H., one of the most innovative highway rigid-frame overpass then in use on the Interstate System. bridges on the U.S. Interstate System, faces an To achieve a 146-ft. clear span with the greatest possible T uncertain future. The bridge, which carries Ash economy of labor and materials, Prowse made use of meth- Street in Londonderry over I-93, is imperiled by the ongo- ods of structural analysis developed throughout the first half ing project to widen the interstate. of the 20th century and of steel fabrication technology that Constructed in 1962, the Prowse Memorial Bridge was had been developing since World War II. Noted both for its a groundbreaking structure that spanned both barrels of engineering and its aesthetics, the bridge received a design the highway without a central pier. Robert James Prowse award from the American Institute of Steel Construction (1906-1969) of what was then the N.H. Department of in 1964. Public Works & Highways (later the New Hampshire The bridge is composed of five parallel steel rigid frames Department of Transportation (NHDOT)) first designed or bents. Each frame is sculpted through careful cutting and the bridge in 1959 for a competition that was intended to arc welding to constantly varying cross sections that reflect foster imaginative and effective uses of steel for interstate the internal stresses at each point in the bridge and impart highway overpass bridges. -

Raised Bog Conservation Study

Raised Bog Conservation Study National Raised Bog SAC Management Plan Strategic Environmental Assessment Environmental Report IBE0802Rp0010 rpsgroup.com/ireland National Raised Bog SAC Management Plan SEA Environmental Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY .................................................................................................. 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION (C HAPTER 2)............................................................................................. 1 1.2 DESCRIPTION OF THE PLAN (C HAPTER 3) .......................................................................... 2 1.3 METHODOLOGY (C HAPTER 4) ........................................................................................... 3 1.4 REVIEW OF RELEVANT PLANS , POLICIES AND PROGRAMMES (C HAPTER 5) .......................... 5 1.5 THE BASELINE ENVIRONMENT (C HAPTER 6) ...................................................................... 6 1.6 STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL OBJECTIVES , TARGETS AND INDICATORS (C HAPTER 7) .......... 8 1.7 ALTERNATIVES (C HAPTER 8) ........................................................................................... 10 1.8 ASSESSMENT (C HAPTER 9) ............................................................................................. 10 1.9 MITIGATION AND MONITORING (C HAPTER 10) .................................................................. 10 1.10 NEXT STEPS (C HAPTER 11) ............................................................................................ 11 1.11 KEY FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS -

Industrial Archaeology

Industrial Archaeology Patrick E. Martin Introduction industrialization. The archaeology of industry has not been a core thematic focus of historical archae- The Industrial Revolution is arguably one of the ologists over the four decades’ development of the most important social phenomena responsible for field, but recently it is drawing increasing attention shaping the modern world. Of course, some histor- and interest. While other scholars have found indus- ians and economists have long contended that this try a fertile field for study, mainstream archaeolo- was or was not a ‘‘revolution’’ in the strictest sense gists have come to it slowly. Any reader can examine of the word and scholars still debate whether the use the products of the Society for Historical Archae- of this metaphor is problematic. Most writers agree ology to evaluate this issue in a North American that this was not an event, but rather a process, with context, or the publications of the Society for Post- predictable precursors and variable rates of change Medieval Archaeology (SPMA) for insight into the from place to place. While earlier shifts in produc- situation in the United Kingdom. If industrializa- tive organization and technological sophistication tion is so important, why have members of these set the stage for the rise of manufacturing and all of two groups of archaeologists paid so little explicit its associated social dimensions, the changes in scale attention to it, and why are they coming to it now? and intensity of productivity, settlement patterns, This chapter will examine the premises laid out distribution, exchange, and control that character- above and attempt to explain the perceived lack of ize industrialized societies have had a profound and critical study, as well as some promising trends and lasting impact on the way we live today. -

Photogrammetry As a New Scientific Tool in Archaeology: Worldwide Research Trends

sustainability Article Photogrammetry as a New Scientific Tool in Archaeology: Worldwide Research Trends Carmen Marín-Buzón 1 , Antonio Pérez-Romero 1, José Luis López-Castro 2, Imed Ben Jerbania 3 and Francisco Manzano-Agugliaro 4,* 1 Graphic Engineering Department, University of Seville, Utrera Road, Km 1, 41013 Sevilla, Spain; [email protected] (C.M.-B.); [email protected] (A.P.-R.) 2 Department of Geography, History and Humanities, University of Almeria, CEIA3, 04120 Almeria, Spain; [email protected] 3 Institut National du Patrimoine, 4 Place du Château, Tunis 1008, Tunisia; [email protected] 4 Department of Engineering, University of Almeria, CEIA3, 04120 Almeria, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Archaeology has made significant advances in the last 20 years. This can be seen by the remarkable increase in specialised literature on all archaeology-related disciplines. These advances have made it a science with links to many other sciences, both in the field of experimental sciences and in the use of techniques from other disciplines such as engineering. Within this last issue it is important to highlight the great advance that the use of photogrammetry has brought for archaeology. In this research, through a systematic study with bibliometric techniques, the main institutions and countries that are carrying them out and the main interests of the scientific community in archaeology related to photogrammetry have been identified. The main increase in this field has been observed since 2010, especially the contribution of UAVs that have reduced the cost of photogrammetric Citation: Marín-Buzón, C.; flights for reduced areas. The main lines of research in photogrammetry applied to archaeology are Pérez-Romero, A.; López-Castro, J.L.; close-range photogrammetry, aerial photogrammetry (UAV), cultural heritage, excavation, cameras, Ben Jerbania, I.; Manzano-Agugliaro, GPS, laser scan, and virtual reconstruction including 3D printing.