Religious Dietary Rules and Their Potential Nutritional and Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April Breakfast Menu

Gustine ISD Pancakes Syrup Sausage Milk and Juice Variety Served Daily Pineapple HOLIDAY HS Fresh Fruit Served Daily Juice Menu Subject to Change Milk Biscuits Pancake Wrap Breakfast Pizza Cinnamon Roll Gravy Syrup HOLIDAY Pears Eggs Yogurt Sausage Juice Bacon Mandarin Oranges Peaches Mixed Fruit Milk Juice Juice Juice Milk Milk Milk Pancakes Cheesy Toast Chicken-n-Biscuit Breakfast Bread Breakfast Burritos Bacon Sausage Peaches Yogurt Hashbrowns Pineapple Pears Juice Mixed Fruit Mandarin Oranges Syrup Juice Milk Juice Juice Juice Milk Milk Milk Milk Sausage Kolache Cheese Omelet Waffles Breakfast Pizza Donuts Yogurt Toast Sausage Mandarin Oranges Sausage Peaches Pineapple Syrup Juice Mixed Fruit Juice Juice Pears Milk Juice Milk Milk Juice Milk Milk Biscuit Pancakes Breakfast Burritos Gravy Breakfast Bread Sausage Hashbrowns Eggs Yogurt Bacon Syrup Mixed Fruit Pineapple HOLIDAY Pears Peaches Juice Juice Juice Juice Milk Milk Milk Milk Art contest deadline April 2 “Moon milk” The moon is more than 200,000 miles away from the Earth. At this distance it takes about three full days for astronauts to travel from the Earth’s surface to land on the moon. Because it is Earth’s closest neighbor, we have been able to gain more knowledge about it than any other body in the Solar System besides the Earth. The moon is also the brightest object in the night sky. Today, astronomers know that the moon is slowly moving away from the Earth. But at the rate it is traveling, about 1.5 inches per year, it will be lighting up our night sky for a long time. -

Dairy Food Consumption, Production and Policy in Japan

Japanese Consumer Demand for Dairy Products Isabelle Schluep Campo (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich) John C. Beghin* (Iowa State University) Contributed paper prepared for presentation at the International Association of Agricultural Economists Conference, Gold Coast, Australia, August 12-18, 2006 Abstract: We econometrically estimate consumer demand for dairy products in Japan using time series data for 1960-2003. We identify economic, cultural, and demographic forces that have been influencing dairy consumption patterns. We use the Almost Ideal (AI) Demand System by Deaton and Muellbauer and its variant, the Semiflexible Almost Ideal (SAI) Demand System developed by Moschini to impose concavity locally by reducing the rank of the Hessian of the expenditure function. We estimate three specifications: a full system comprising of four dairy products (fluid milk, powder milk, cheese, and butter), and an all other- goods aggregate; a subsystem for food made of four dairy goods and an all-other-food aggregate; and a sub-system of the four dairy products. The minimum distance estimator is used to estimate the demand system. We find that expenditure responses are positive, except for butter demand; own-price responses are large in absolute value; and non-price factors are important determinants of Japanese dairy consumption. JEL: Q11, Q17, Q18 Keywords: dairy demand, Japan, demand system, cheese, fluid milk. * Contact Author: John Beghin. CARD and Economics, 568 Heady Hall, ISU Ames Iowa 50011-1070 USA. Phone: 1 515 294 5811; Fax: 1 515 294 6336; email: [email protected]. Without implicating them, we thank F. Dong, G. Moschini, D. Sumner, and N. Suzuki for discussions and comments. -

Paper No. 13 FOOD ADDITIVES Module No. 31 Dairy Ingredients in Food Applications

Paper No. 13 FOOD ADDITIVES Module No. 31 Dairy ingredients in food applications - I (Baking, Confectionery, Sauces) Introduction Milk is considered to be an adequate source of valuable macronutrients (fat, protein, lactose), vitamins and micronutrients (minerals), making it a ‘wholesome food’. It can serve as an excellent carrier product for extra nutrient, and if enriched or fortified it can satisfy the nutritional needs of the population. Non-dairy ingredients find a critical role in synergy of the chemical constituents of dairy foods to enhance their sensory, nutritional profile, at the same time influencing the cost of the resultant product. Dramatic increases in the cost of milk have sent prices of milk ingredients skyrocketing – threatening the profitability of dairy and other food products. Driven by consumer’s lifestyle, their demographics, socio-economic, cultural background and their environment, a whole range of new product formulations have evolved to suit the palate of the varied consumers. The consumer is shifting towards ‘light’ foods with low calories and adopting ‘functional foods’ that is going to improve their health and well-being too. In fact, blending functional ingredients into dairy based foods helps increased sale of dairy foods (Berry, 2002). Hence, there is a need to merge non-dairy ingredients with dairy based ingredients and products to attain the above mentioned objectives with attendant savings in cost, enhanced appearance, taste, texture and even functionality. The role played by dairy ingredients in baked goods, confectionery foods and sauces are discussed in depth in this module. I. Dairy ingredients in Baking industry Milk solids in baked goods Milk, butter, buttermilk, yoghurt, kefir, whey, quarg and dried milk protein or SMP have been tried out as one of the valued ingredient in various types of bread, and whole milk, butter and fresh cheese in fine bakery goods. -

Indiana Dairy Product Buyer's Guide

Indiana Dairy Product Buyer’s Guide 2020 Indiana has a strong artisan dairy community. Specialty products are hand-crafted locally under private labels. On farmsteads, products are processed on the same farm where animals are raised and milked. Ice Dairy Processor Location Contact Milk Cheese Cream Yogurt Butter Amish Country Dairy* Shipshewana 260-768-3236 l Bliss Artisan Ice Creamw Tell City blissartisan.com l Brown’s Ice Creamw Valparaiso valpovelvet.com l Caprini Creamery*vw Spiceland caprinicreamery.com l Capriole Dairyvw Greenville capriolegoatcheese.com l Crystal Springs Creamery*w Osceola crystalspringscreamery.com l l l Dandy Breeze Creamery*w Sheridan dandybreezedairy.com l Family Tyme Creameryw Williamsburg 765-886-5567 l Gelato DaVinci Fishers/Carmel gelatodavinci.com l Glover’s Ice Cream Frankfort gloversicecream.com l Goat and Small*vw Silver Lake 260-901-0527 l l l Goat Milk Stuff*vw Scottsburg goatmilkstuff.com l l l l Heritage Ridge Creamery Middlebury heritageridgecreamery.com l Homestead Farms Shipshewana 260-652-1077 l Hufford Family Farm* N. Manchester 260-901-0928 l J2K Capraio*vw Walkerton 574-586-9522 l Jacobs & Brichford*w Connersville jandbcheese.com l Lick Ice Creamw Indianapolis lickicecream.tumblr.com l Lloyds Ice Creamw Evansville licsdeliandicecream.com l MammaMia Gelato Carmel mammamiaindy.com l Meadow Valley Cheese* Rockville 765-597-2306 l Meyer Ice Creamw New Albany meyericecream.com l Nicey Treatw Indianapolis niceytreat.com l Risin’ Creek*vw Martinsville risincreek.com l Round Barn Creameryw Winamac -

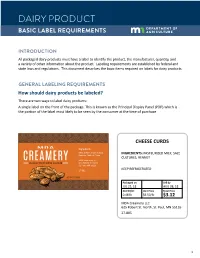

Dairy Prodcut Labeling

DAIRY PRODUCT BASIC LABEL REQUIREMENTS INTRODUCTION All packaged dairy products must have a label to identify the product, the manufacturer, quantity, and a variety of other information about the product. Labeling requirements are established by federal and state laws and regulations. This document describes the basic items required on labels for dairy products. GENERAL LABELING REQUIREMENTS How should dairy products be labeled? There are two ways to label dairy products: A single label on the front of the package. This is known as the Principal Display Panel (PDP) which is the portion of the label most likely to be seen by the consumer at the time of purchase. CHEESE CURDS MDA MDA Ingredients Milk, Cream, Sugar, Cocoa, PASTEURIZED MILK, SALT, Peanuts, Natural Flavor INGREDIENTS: CULTURES, RENNET CREAMERY MDA Creamery LLC CHOCOLATY PEANUT BUTTER ICE CREAM CREAMERY CHOCOLATY PEANUT BUTTER ICE CREAM 625 Robert St. North St. Paul, MN 55155 27-805 KEEP REFRIGERATED 1/2 PINT (273 ML) Packaged on Sell by JUL 25, 18 AUG 08, 18 Net Wt/Ct Unit Price Total Price 0.48 lb $6.50/lb $3.12 MDA Creamery LLC 625 Robert St. North, St. Paul, MN 55155 27-805 MDA Ingredients Serving Size 1/2 Cup (70g) Milk, Cream, Sugar, Vanilla Extract Servings Per Container 4 MDA Creamery LLC Amount per Serving 625 Robert St. North Calories 70 Calories From Fat 25 St. Paul, MN 55155 % Daily Value 27-805 Total Fat 3g 5% Saturated Fat 1.5g 7% Trans Fat 0g CREAMERY Cholesterol 43mg 14% CHOCOLATY PEANUT BUTTER ICE CREAM Sodium 89mg 4% Total Carbohydrates 12g 4% Dietary Fiber 4g 16% Sugar 4g Erythritol 4g Protein 7g Vitamin A 3% Vitamin C 0% Calcium 7% Iron 1% 1 PINT (473 ML) 1 Another way is to divide the information into two labels, PDP and Information Panel (IP). -

An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide

AN AHIMSA CRISIS: YOU DECIDE An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 1 2Prakrit Bharati academy,An Ahimsa Crisis: Jai YouP Decideur Prakrit Bharati Pushpa - 356 AN AHIMSA CRISIS: YOU DECIDE Sulekh C. Jain An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 3 Publisher: * D.R. Mehta Founder & Chief Patron Prakrit Bharati Academy, 13-A, Main Malviya Nagar, Jaipur - 302017 Phone: 0141 - 2524827, 2520230 E-mail : [email protected] * First Edition 2016 * ISBN No. 978-93-81571-62-0 * © Author * Price : 700/- 10 $ * Computerisation: Prakrit Bharati Academy, Jaipur * Printed at: Sankhla Printers Vinayak Shikhar Shivbadi Road, Bikaner 334003 An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 4by Sulekh C. Jain An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide Contents Dedication 11 Publishers Note 12 Preface 14 Acknowledgement 18 About the Author 19 Apologies 22 I am honored 23 Foreword by Glenn D. Paige 24 Foreword by Gary Francione 26 Foreword by Philip Clayton 37 Meanings of Some Hindi & Prakrit Words Used Here 42 Why this book? 45 An overview of ahimsa 54 Jainism: a living tradition 55 The connection between ahimsa and Jainism 58 What differentiates a Jain from a non-Jain? 60 Four stages of karmas 62 History of ahimsa 69 The basis of ahimsa in Jainism 73 The two types of ahimsa 76 The three ways to commit himsa 77 The classifications of himsa 80 The intensity, degrees, and level of inflow of karmas due 82 to himsa The broad landscape of himsa 86 The minimum Jain code of conduct 90 Traits of an ahimsak 90 The net benefits of observing ahimsa 91 Who am I? 91 Jain scriptures on ahimsa 91 Jain prayers and thoughts 93 -

Dairy Sector

The ongoing modernisation of China’s dairy sector The ongoing modernisation of China's dairy sector -2 - The ongoing modernisation of China’s dairy sector Content Introduction 4 Dairy farming sector 6 Stagnating growth and farm consolidation 7 Dairy farm modernisation 11 High production costs 13 Geographic and seasonal mismatch 16 Ambitious growth target 17 Future dairy farm modernisation 18 Dairy processing sector 19 Consolidated industry structure Vertical 20 integration and cross-border expansion 22 Product mix 23 UHT milk 24 Fresh milk 24 Yogurt 25 Ice cream 27 Cheese 29 Infant milk formula 30 Government policies for the dairy industry 34 Keys to success 36 The ongoing modernisation of China’s dairy sector Introduction China has long aimed to increase dairy consumption in Between 1980 and 2006, China’s raw milk production order to improve public health and nutrition. In 2006, increased by more than 2000% from 1.4 million tonnes Prime Minister Wen Jiabao said “I have a dream that to over 30 million tonnes. Production peaked at 33 every Chinese person, especially children, can drink million tonnes in 2012. Consumption has continued to one jin of milk per day” (note: one jin is equal to 0.5 increase, but dairy production has declined. More than kg).1 The 2009 Dairy Industry Policy stated that per 30% of China’s dairy products (measured in raw milk capita milk consumption was a key indicator of the equivalents) now come from imports, compared to country’s standard of living.2 China’s per capita dairy about 5% in 2007.6, 7 consumption is -

Jain Veganism: Ancient Wisdom, New Opportunities

religions Article Jain Veganism: Ancient Wisdom, New Opportunities Christopher Jain Miller 1 and Jonathan Dickstein 2,* 1 Department of Theological Studies, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, CA 90045, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Religious Studies, University of California Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA 93101, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This article seeks to elevate contemporary Jain voices calling for the adoption of a vegan lifestyle as a sign of solidarity with the transnational vegan movement and its animal rights, envi- ronmental protection, and health aspirations. Just as important, however, this article also seeks to present some of the unique features of contemporary Jain veganism, including, most specifically, Jain veganism as an ascetic practice aimed at the embodiment of non-violence (ahim. sa¯), the eradication (nirjara¯) of karma, and the liberation (moks.a) of the Self (j¯ıva). These are distinctive features of Jain ve- ganism often overlooked and yet worthy of our attention. We begin the article with a brief discussion of transnational veganism and Jain veganism’s place within this global movement. This is followed by an overview of Jain karma theory as it appears in the Tattvartha¯ Sutra¯ , an authoritative diasporic Jain text. Next, we present two case studies of contemporary Jain expressions of veganism: (1) The UK-based organization known as “Jain Vegans” and (2) The US-based organization known as “Vegan Jains”. Both organizations have found new opportunities in transnational veganism to practice and embody the virtue of ahim. sa¯ as well as Jain karma theory. As we will show, though both organizations share the animal, human, and environmental protection aspirations found in transnational veganism, Jain Vegans and Vegan Jains simultaneously promote ahim. -

Dairy Product Regulation

CHAPTER 4.1-25 DAIRY PRODUCT REGULATION 4.1-25-01. Definitions. 1. "Cheese factory" means a facility that makes cheese for commercial purposes. 2. "Commissioner" means the agriculture commissioner or the commissioner's designee. 3. "Condensery" means a facility where condensed or evaporated milk is produced. 4. "Dairy animal" means any mammal maintained for the commercial production of milk to be offered for sale for use in the processing or manufacturing of milk or dairy products. 5. "Dairy farm" means a place where one or more dairy animals are kept. 6. "Dairy product" includes milk, cream, sour cream, butter cream, skimmed milk, ice cream, whipped cream, flavored milk or skim milk drink, dried or powdered milk, cheese, cream cheese, cottage cheese, creamed cottage cheese, ice cream mix, sherbet, condensed milk, evaporated milk, or concentrated milk. 7. "Department" means the department of agriculture. 8. "Distributor" means a person that provides storage, transportation, delivery, or distribution of dairy products to any person who sells dairy products. 9. "Drying plant" means a facility that manufactures dry milk products by removing water from milk or milk products. 10. "Filled dairy products" means any milk, cream, or skimmed milk, or any combination of them, whether or not condensed, evaporated, concentrated, frozen, powdered, dried, or desiccated, or any food product made or manufactured from those products, to which has been added, blended, or compounded with, any fat or oil, other than milk fat, to imitate a dairy product. "Filled dairy products" may not be construed to mean or include: a. Any distinctive proprietary food compound not readily mistaken for a dairy product, if the compound is customarily used on the order of a physician and is prepared and designed for medicinal or special dietary use and prominently so labeled; b. -

The Jewish Dietary Laws and Their Foundation

THE JEWISH DIETARY LAWS AND THEIR FOUNDATION The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation THE JEWISH DIETARY LAWS AND THEIR FOUNDATION (1994 Third Year Paper) Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:8889478 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA S. $i A5~ THE JEWISH DIETARYn LAWS AND THEIR FOUNDATION final paper 403 8983 00 Professor P.B. Hutt Winter 1994 1 403 8983 00 1 I. Introduction While food and drug law has made its greatest contributions to the health and welfare of society over the past two centuries, it is indisputable that the history of this body of law is much older than two hundred years.1 Soon after man realized he needed to eat, he recognized a need to establish rules and regulations governing the sale, preparation and handling of food. Perhaps the oldest documented set of food laws are the Jewish dietary laws, also known by the Hebrew term, kashrut, from which the word kosher is derived. Unlike most laws related to food, which are enacted by society through government or other rulemaking bodies, Jewish dietary laws are believed to be conceptualizations of divine will that were expressed to Moses at Mount Sinai and transcribed in the Old Testament.2 Intellectual curiosity and an interest in the evolution of food and drug law compel both Jews and Gentiles to study the Jewish dietary laws. -

YOGURT Ancient Food in the 21St Century

YOGURT ancient food in the 21st century Ricardo Weill This book is the result of extensive research carried out in collaboration with more than ten specialists in general health, nutrition, paediatrics, biochemistry and microbiology, among other disciplines. All specialists consulted offered state-of-the-art scientific and academic information, which was then combined and woven into this single text describing yogurt from its very origin to industrial manufacture. YOGURT ANCIENT FOOD IN THE 21ST CENTURY Weill, Ricardo YOGURT, ancient food in the 21st century/Ricardo Weill; compiled by Alejandro Ferrari; illustrated by Florencia Abd and Juliana Vido. First edition, Buenos Aires: Asociación Civil Danone para la Nutrición, la Salud y la Calidad de Vida, 2017. 180 p.: ill.; 21 x 14 cm. ISBN 978-987-28033-4-6 1. Dairy Industry 2. History I. Ferrari, Alejandro, comp. II. Abd, Florencia, ill. III. Vido, Juliana, ill. IV. Title. CDD 338.1762142 First edition 2017 All rights reserved. This book is subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. © 2017 INDEX FOREWORD 9 INTRODUCTION 13 FOOD FERMENTATION: CHANCE AND OPPORTUNITY 16 YOGURT IN THE HISTORY OF MAN 28 THE PIONEERING WORK OF ÉLIE METCHNIKOFF 42 YOGURT PRODUCTION 56 MICROBIOTA: THE INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY 68 KEFIR, YOGURT’S OLDER BROTHER 80 YOGURT AND NATURAL IMMUNITY 90 YOGURT AND HEALTH PROMOTION 106 WHAT DO ARGENTINES EAT? 120 CONTROVERSIES IN NUTRITION 136 YOGURT IN EVERYDAY COOKING, BY NARDA LEPES 148 RECIPES WITH YOGURT, BY NARDA LEPES 152 REFERENCES 162 FOREWORD The first draft for this book was drawn up in Berlin in 2015, during the 12th European Nutrition Conference (Federation of European Nutrition Societies), over dinner with my dear friend Esteban Carmuega. -

November 26, 2018 Submitted Electronically Scott Gottlieb

COMMITTEE ON ANIMAL LAW CHRISTOPHER WLACH CHAIR November 26, 2018 PHONE: (917) 747-7297 [email protected] SEJAL SANGHVI SECRETARY PHONE: (917) 968-6251 [email protected] Submitted Electronically Scott Gottlieb, Commissioner c/o Dockets Management Staff (HFA–305) Food and Drug Administration 5630 Fishers Lane, Rm. 1061 Rockville, MD 20852 Re: Docket No. FDA–2018–N–3522, Use of the Names of Dairy Foods in the Labeling of Plant-Based Products Dear Commissioner Gottlieb: The Animal Law Committee (“Committee”) of the New York City Bar Association writes in response to the FDA’s request for comments on the topic of the “Use of the Names of Dairy Foods in the Labeling of Plant-Based Products.” As background, the New York City Bar Association is an independent non-governmental organization of more than 24,000 lawyers, law professors, and government officials, principally from New York City but also from throughout the United States and 50 other countries. Its Animal Law Committee is the first committee of its kind in the United States. In 2018, we presented a public program that explored issues relating to plant-based milks with an attorney who represents a plant-based food organization, an attorney who represents dairy farmers, and the past chair of the Committee.1 We also submitted a comment to Congress opposing the DAIRY PRIDE Act2 and a letter to the FDA in response to a request from 32 members of 1 Say It Ain’t Soy! The Labeling of Plant-Based Alternative Foods (Mar. 22, 2018), https://www2.nycbar.org/mp3/Podcasts/media/say_it_aint_soy_-_the_labeling_of_plant-based_alternative_foods- _3.22.2018.mp3.