The Cinematic Experience, Filmic Space, and Transitional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maggie-Dp.Pdf

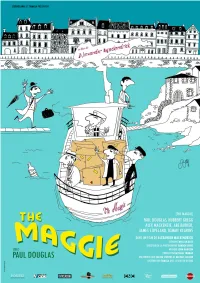

STUDIOCANAL et TAMASA présentent un film de Alexander Mackendrick ç Version restaurée UK - Durée 1h32 ç Sortie le 16 décembre 2015 ç Presse Frédérique Giezendanner [email protected] T. 06 10 37 16 00 Distribution TAMASA [email protected] T. 01 43 59 01 01 Visuels téléchargeables sur www.tamasadiffusion.com SYNOPSIS Le Capitaine de la « Maggie », Mac Taggart, ne possède pas suffisamment d’argent pour faire réparer son bateau qui tient la mer par miracle, malgré les réticences des autorités portuaires. Par suite d’un malentendu, Pusey, représentant un riche Américain, Marshall, lui confie le transport d’un matériel couteux destiné à la modernisation d’un château. Découvrant la supercherie, Marshall, atterré, essaye de récupérer son précieux chargement. Mais après bien des incidents, bien des événements inattendus avec ce curieux équipage, le chargement finira au fond de la mer. Mais Mac Taggart conserve l’argent que lui a remis Marshall pour faire réparer son vieux bateau. ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK Alexander Mackendrick est né à Boston, dans l’État du Massachusetts. À 6 ans, son père meurt emporté par la grippe « espagnole ». Sa mère, qui devait trouver du travail pour survivre, décide de devenir couturière. Elle céda la garde de son fils au grand-père qui vivait en Écosse. C’est ainsi qu’à l’âge de sept ans, Mackendrick revient sur la terre de ses aïeux. Il vit une enfance très solitaire et difficile. Après des études d’art, il part s’installer à Londres dans les années 30 pour travailler comme directeur artistique. Entre 1936 et 1938, Mackendrick est l’auteur du script de publicités cinématographiques. -

MAESTROS DEL CINE CLÁSICO (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (En El 105 Aniversario De Su Nacimiento)

Cineclub Universitario / Aula de Cine P r o g r a m a c i ó n d e febrero 2 0 1 7 MAESTROS DEL CINE CLÁSICO (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (en el 105 aniversario de su nacimiento) Fotografía: Proyector “Marín” de 35mm (ca.1970). Cineclub Universitario Foto:Jacar [indiscreetlens.blogspot.com] (2015). El CINECLUB UNIVERSITARIO se crea en 1949 con el nombre de “Cineclub de Granada”. Será en 1953 cuando pase a llamarse con su actual denominación. Así pues en este curso 2016-2017, cumplimos 63 (67) años. FEBRERO 2017 MAESTROS DEL CINE CLÁSICO (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (en el 105 aniversario de su nacimiento) FEBRUARY 2017 MASTERS OF CLASSIC CINEMA (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (105 years since his birth) Viernes 3 / Friday 3th • 21 h. WHISKY A GOGÓ (1949) (WHISKY GALORE!) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 7 / Tuesday 7th • 21 h. EL HOMBRE VESTIDO DE BLANCO (1951) (THE MAN IN THE WHITE SUIT) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Viernes 10 / Friday 10th • 21 h. MANDY (1952) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 14 / Tuesday 14th • 21 h. EL QUINTETO DE LA MUERTE (1955) (THE LADYKILLERS) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Viernes 17 / Friday 17th • 21 h. CHANTAJE EN BROADWAY / EL DULCE SABOR DEL ÉXITO (1957) (SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 21 / Tuesday 21th • 21 h. SAMMY, HUIDA HACIA EL SUR (1963) (SAMMY GOING SOUTH) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Todas las proyecciones en la Sala Máxima de la ANTIGUA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA (Av. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

Sammy Going South

Sammy Going South ( US = “A Boy Ten Feet Tall” ) UK : 1963 : dir. Alexander Mackendrick : British Lion / Seven Arts : 128 min prod: Hal Mason : scr: Denis Cannan : dir.ph.: Erwin Hillier Fergus McClelland ………….………………………………………………………………………… Edward G Robinson; Constance Cummings; Harry H Corbett; Paul Stassino; Zia Moyheddin; Zena Walker; Orlando Martins; John Turner; Jack Gwillim; Patricia Donahue; Jared Allen; Guy Deghy; Frederick Schiller; Swaleh; Tajiri; Faith Brown Ref: Pages Sources Stills Words Ω Copy on VHS Last Viewed 3253b 6½ 13 7 2,777 Yes May 2001 The doctor gives Sammy a few pointers on his way… Source: The Moving Picture Boy Leonard Maltin’s Movie and Video Guide Halliwell’s Film Guide review: review: “A 10-year old boy is orphaned in Port Said and “Colourful, charming film about orphaned boy hitch-hikes to his aunt in Durban. travelling through Africa alone to reach his Disappointing family-fodder epic in which the Aunt, who lives in Durban. Cut to 88 minutes mini-adventures follow each other too for American release, footage was restored for predictably.” the TV print. *** ” Speelfilm Encyclopedie review - identical to above Edward G Robinson, reeling under the name of “Cocky Wainwright”, lends a human dimension to an otherwise bland travelogue. Source: Films & Filming May 63 Movies on TV and Videocassette 1988-89 review: The Time Out Film Guide review: “Nice family entertainment, thanks to the “While widely regarded as an example of exotic locale and a good human interest story of Mackendrick’s decline after the masterpiece a young lad trying to cross Africa alone to reach that was "SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS", this his aunt. -

2003 Radio and TV

http://pandora.nla.gov.au/pan/42534/20040608-0000/users.senet.com.au/_trisc/RadioTV.html Tristram Cary Rad io and Television NB: When not otherwise stated, scores are for BBC radio Year Title/ Comme nt etc Prod/Dir 1954The Saint and the Sinner (Tirso de Molina) Frederick Bradnum The Trickster of Seville & The Guest of Stone Frederick Bradnum (Tirso de Molina) Belshazzar's Feast (Calderon) Frederick Bradnum 1955 The Jackdaw (BBC TV) Dorothea Brooking The Ghost Sonata (Strindberg) Frederick Bradnum (E) The Japanese Fishermen .Suite on CD Terence Tiller Soundings 1956 Cranford (Mrs Gaskell) 8-part serial Raymond Raikes 1957 The Tinderbox (Aaron Kramer) Terence Tiller 1959 The Master Cat (Dillon) Francis Dillon Maid Marian (Peacock) (Excerpts as Songs for Christopher Holme Maid Marian (1998)) Eileen Aroon (Dillon) Francis Dillon (E) East of the Sun and West of the Moon Louis Macneice (Louis Macneice) (E) The Children of Lir (H.A.L. Craig) Suite on Douglas Cleverdon CD Soundings (E) They Met on Good Friday (Louis Louis Macneice Macneice) (E) Macbeth Charles Lefeaux 1960 (E) The End of Fear (Denis Saurat) Terence Tiller King Lear Charles Lefeaux The Ballad of Peckham Rye (Muriel Spark) Christopher Holme First version Timon of Athens Charles Lefeaux (E) The Infernal Machine (La Machine H.B. Fortuin Infernale - Cocteau) 1961 The Danger Zone (Muriel Spark) Christopher Holme The Flight of the Wild Geese (Dillon) Francis Dillon The Flight of the Earls (H.A.L. Craig) Douglas Cleverdon The World Encompassed (Dillon) Francis Dillon 1962 The Ballad of -

First Ever 4K Uhd Restoration

FIRST EVER 4K UHD RESTORATION ONE OF THE BEST BRITISH COMEDIES EVER MADE CELEBRATES ITS 65TH ANNIVERSARY WITH 4K UHD RESTORATION AND INTERNATIONAL THEATRICAL & HE RELEASE WATCH THE NEW TRAILER HERE DOWNLOAD THE NEW TRAILER HERE DOWNLOAD NEW POSTER HERE September 24th 2020: To celebrate the 65th anniversary of Ealing Studios’ flawless THE LADYKILLERS, STUDIOCANAL will be releasing the first ever 4k restoration of the 1955 black comedy from the original 3- strip Technicolor negative, showcasing director Alexander Mackendrick’s vision in its full glory. THE LADYKILLERS follows the hilarious capers of a group of small-time crooks, taking on more they can handle in the form of their sweet, but slightly dotty, elderly landlady Mrs Wilberforce (BAFTA Award-winning actress Katie Johnson; How To Murder A Rich Uncle). This group of seedy misfits are planning a security van robbery and rent a room from Mrs Wilberforce in her rickety Victorian house next to King’s Cross station from which to base their operation. To conceal their true purpose, they pose as a string quartet, though they cannot play a note and are in fact miming to a recording of Boccherini’s Minuet. The gang pull off the robbery but none of them could have predicted that their greatest obstacle to escaping with the loot would be their tiny hostess. THE LADYKILLERS features an all-star line-up of the finest comedy actors of the era: Alec Guinness (Kind Hearts and Coronets, The Lavender Hill Mob) plays the gang’s mastermind ‘Professor Marcus’; Cecil Parker (A French Mistress) is Claude otherwise known as ‘Major Courtney’; Peter Sellers (I’m Alright Jack) is Harry aka ‘Mr Robinson’; Herbert Lom (The Pink Panther) is Louis aka ‘Mr Harvey’ and Danny Green (A Kid For Two Farthings) plays One Round also known as ‘Mr Lawson’. -

Alexander Mackendrick: Filmmaker, Teacher & Theorist a Centennial Celebration

FILM AT REDCAT PRESENTS Wed Feb 6 | 8:30 pm | Jack H. Skirball Series $10 [students $8, CalArts $5] Alexander Mackendrick: Filmmaker, Teacher & Theorist A Centennial Celebration The esteemed director of Sweet Smell of Success (1957) and The Ladykillers (1955), Alexander Mackendrick (1912–1993) was a pivotal figure in the history of CalArts, and his work and writings remain a major influence on contemporary narrative directors and screenwriters. For this celebration of the artist’s multifaceted contributions, Paul Cronin (editor of Mackendrick’s seminal book On Film-Making) is joined by two CalArts alums, director James Mangold and author and filmmaker F.X. Feeney. Together they honor the man who, as Dean of the School of Film/Video at CalArts and throughout his nearly 25 years of teaching, shaped an institution and inspired generations of filmmakers. This lively discussion reveals Mackendrick through personal reminiscences, film clips and critical observations on his work as a filmmaker, teacher and theorist. In person: Paul Cronin, F.X. Feeney and James Mangold “ ‘Process, not product’ was [Mackendrick’s] mantra to his students. The creative process—not the creative method, or the creative system. The process. Which never stops.” —Martin Scorsese One of the most distinguished directors ever to emerge from the British film industry, Alexander “Sandy” Mackendrick was born in the US to Scottish parents. Raised in Scotland, Mackendrick studied at the Glasgow School of Art. Afterward, he worked as a commercial illustrator, soon gravitating to making films, the first being animated advertisements followed by numerous live action short documentaries. Mackendrick’s feature debut was the Ealing Studios comedy classic Whisky Galore (1949). -

The Man in the White Suit, Dir. Alexander Mackendrick (1951)

The Man in the White Suit, dir. Alexander Mackendrick (1951) The Man in the White Suit (TMITWS) is rarely mentioned in relation to design practice, beyond its relevance to “smart fabrics,” but every design professional should see this cautionary tale of an individual battling an industry. [1] The film‟s obsessive protagonist, Sidney Stratton (Alec Guinness) works as a cleaner at Corland textile mill while secretly pursuing chemical experiments. Upon discovery, he is sacked and moves to Birnley mill where his technical expertise gains him access to the research lab. Birnley‟s daughter (Joan Crawford) persuades her father to give Stratton a contract and facilities. He no longer needs to improvise his experiments on borrowed bench space and is granted exclusive use of lab facilities, to avoid industrial espionage. The dangerous nature of his experiments (and his disregard for personal safety) ensures that the physical destruction of his workshop serves as a visual manifestation of the fate of his invention. His fabric, which never gets dirty or tears, can mimic a range of existing applications. Its durability threatens the entire textile industry and it is opposed by trade unions and mill owners alike. The title suggests both savior (as Stratton‟s champion/love-interest Crawford sees it) and madman (The Man in the White Straightjacket?): ultimately, Stratton‟s determination to realize his invention remains undefeated. [2] Adapted from a play by Roger MacDougall, TMITWS was released in the UK in 1951 by the celebrated Ealing Studios in the year that the Festival of Britain promoted understanding of British design, culture and industry. -

MANDY Un Film De Alexander Mackendrick

Téléchargez les images dans les préférences de votre service de messagerie ou cliquez ici pour voir l'e-mail sur le web GROUPE PATRIMOINE/RÉPERTOIRE FICHE-EXPLOITANT MANDY un film de Alexander Mackendrick Tamasa Distribution 05 avril 2017 Un film d'Alexander Mackendrick Royaume-Uni - 1952 - 1h33 - VOSTF Mandy, sourde à sa naissance, est tiraillée entre ses parents qui ne sont pas d’accord sur l’éducation à lui donner. Sa mère l’inscrit dans une institution spécialisée où un professeur la convainc que, grâce à ses méthodes, Mandy pourra peu à peu apprendre à parler. Jaloux du professeur, le père retire l’enfant de l’institution… Le contexte La difficile reconnaissance de la surdité Les années 50 ont été une période de transition pour les malentendants. Bien que de nombreuses personnes considéraient à cette époque que la surdité était une maladie que l’on devait soigner, cette décennie vit l’éclosion d’associations pour sourds, ainsi que la naissance de la « culture sourde ». Cependant, hors de cette communauté, un préjugé répandu se traduisait par l’utilisation du terme «idiot» pour décrire des personnes qui ne pouvaient pas parler (souvent les personnes sourdes n’apprenaient pas à parler). C’est ce monde qui est dépeint dans MANDY. Des échos intimes pour Alexander Mackendrick L’histoire avait une résonance personnelle pour Alexander Mackendrick. Bien que né aux USA, il avait émigré en Ecosse pour vivre avec son grand-père après le décès de son père à la fin de la Première Guerre Mondiale, causé par l’épidémie de grippe. Sa mère devant organiser sa propre vie, l’avait envoyé en Ecosse pour un séjour temporaire qui devint permanent. -

The Ladykillers UK 1955

The Ladykillers UK 1955 Directed by Alexander Mackendrick Produced by Michael Balcon and Seth Holt for Ealing Studios Written by WilliamWilliam Rose Original music by TristramTristram Cary Cinematography by Otto Heller Film Editing by Jack Harris Art Direction by Jim Morahan Costume Design by Anthony Mendleson Sound supervisor: Stephen Dalby Runtime: 97 mins Leading players Alec Guinness Professor Marcus Cecil Parker Major Courtney Herbert Lom Louis, 'Mr Harvey' Peter Sellers Harry, 'Mr Robinson' Danny Green One-Round, 'Mr Lawson' Jack Warner Police Supt Dixon Katie Johnson Louisa Wilberforce Philip Stainton Police Sergeant Frankie Howerd Barrow boy The gang (from the left): Harry, Louis, The Major, Professor Marcus and One Round Kenneth Connor Taxi Driver Synopsis ‘Professor’ Marcus is the leader of an unlikely gang of bank robbers, including the conman Major Courtney, hapless boxer One-Round, mysterious Louis and teddy-boy Harry. The Professor rents the upstairs room of an isolated Victorian house that backs onto the railway line near Kings Cross station. He tells the landlady Mrs Wilberforce that the gang are a string quintet who are meeting to rehearse. Their real intention is to plan a robbery. The gang do not know that Mrs Wilberforce is well known at the local police station as a mild eccentric. The gang play records to fool the old lady whilst planning the robbery. During one planning session, the parrot, ‘General Gordon’, escapes and the gang, without the guiding hand of the Professor, cause havoc trying to re-capture him. The robbery is staged without delay. The gang steal four cases of money in a carefully staged roadside attack on a security van.