Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/26/2021 01:59:35PM Via Free Access

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Widescreen Weekend 2007 Brochure

The Widescreen Weekend welcomes all those fans of large format and widescreen films – CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, Cinerama and Imax – and presents an array of past classics from the vaults of the National Media Museum. A weekend to wallow in the best of cinema. HOW THE WEST WAS WON NEW TODD-AO PRINT MAYERLING (70mm) BLACK TIGHTS (70mm) Saturday 17 March THOSE MAGNIFICENT MEN IN THEIR Monday 19 March Sunday 18 March Pictureville Cinema Pictureville Cinema FLYING MACHINES Pictureville Cinema Dir. Terence Young France 1960 130 mins (PG) Dirs. Henry Hathaway, John Ford, George Marshall USA 1962 Dir. Terence Young France/GB 1968 140 mins (PG) Zizi Jeanmaire, Cyd Charisse, Roland Petit, Moira Shearer, 162 mins (U) or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 hours 11 minutes Omar Sharif, Catherine Deneuve, James Mason, Ava Gardner, Maurice Chevalier Debbie Reynolds, Henry Fonda, James Stewart, Gregory Peck, (70mm) James Robertson Justice, Geneviève Page Carroll Baker, John Wayne, Richard Widmark, George Peppard Sunday 18 March A very rare screening of this 70mm title from 1960. Before Pictureville Cinema It is the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The world is going on to direct Bond films (see our UK premiere of the There are westerns and then there are WESTERNS. How the Dir. Ken Annakin GB 1965 133 mins (U) changing, and Archduke Rudolph (Sharif), the young son of new digital print of From Russia with Love), Terence Young West was Won is something very special on the deep curved Stuart Whitman, Sarah Miles, James Fox, Alberto Sordi, Robert Emperor Franz-Josef (Mason) finds himself desperately looking delivered this French ballet film. -

Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display Maggie Mason Smith Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints Presentations University Libraries 5-2017 Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display Maggie Mason Smith Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Mason Smith, Maggie, "Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display" (2017). Presentations. 105. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres/105 This Display is brought to you for free and open access by the University Libraries at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Presentations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display May 2017 Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display Photograph taken by Micki Reid, Cooper Library Public Information Coordinator Display Description The Summer Blockbuster Season has started! Along with some great films, our new display features books about the making of blockbusters and their cultural impact as well as books on famous blockbuster directors Spielberg, Lucas, and Cameron. Come by Cooper throughout the month of May to check out the Star Wars series and Star Wars Propaganda; Jaws and Just When you thought it was Safe: A Jaws Companion; The Dark Knight trilogy and Hunting the Dark Knight; plus much more! *Blockbusters on display were chosen based on AMC’s list of Top 100 Blockbusters and Box Office Mojo’s list of All Time Domestic Grosses. - Posted on Clemson University Libraries’ Blog, May 2nd 2017 Films on Display • The Amazing Spider-Man. Dir. Marc Webb. Perf. Andrew Garfield, Emma Stone, Rhys Ifans. -

Maggie-Dp.Pdf

STUDIOCANAL et TAMASA présentent un film de Alexander Mackendrick ç Version restaurée UK - Durée 1h32 ç Sortie le 16 décembre 2015 ç Presse Frédérique Giezendanner [email protected] T. 06 10 37 16 00 Distribution TAMASA [email protected] T. 01 43 59 01 01 Visuels téléchargeables sur www.tamasadiffusion.com SYNOPSIS Le Capitaine de la « Maggie », Mac Taggart, ne possède pas suffisamment d’argent pour faire réparer son bateau qui tient la mer par miracle, malgré les réticences des autorités portuaires. Par suite d’un malentendu, Pusey, représentant un riche Américain, Marshall, lui confie le transport d’un matériel couteux destiné à la modernisation d’un château. Découvrant la supercherie, Marshall, atterré, essaye de récupérer son précieux chargement. Mais après bien des incidents, bien des événements inattendus avec ce curieux équipage, le chargement finira au fond de la mer. Mais Mac Taggart conserve l’argent que lui a remis Marshall pour faire réparer son vieux bateau. ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK Alexander Mackendrick est né à Boston, dans l’État du Massachusetts. À 6 ans, son père meurt emporté par la grippe « espagnole ». Sa mère, qui devait trouver du travail pour survivre, décide de devenir couturière. Elle céda la garde de son fils au grand-père qui vivait en Écosse. C’est ainsi qu’à l’âge de sept ans, Mackendrick revient sur la terre de ses aïeux. Il vit une enfance très solitaire et difficile. Après des études d’art, il part s’installer à Londres dans les années 30 pour travailler comme directeur artistique. Entre 1936 et 1938, Mackendrick est l’auteur du script de publicités cinématographiques. -

The James Bond Quiz Eye Spy...Which Bond? 1

THE JAMES BOND QUIZ EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 1. 3. 2. 4. EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 5. 6. WHO’S WHO? 1. Who plays Kara Milovy in The Living Daylights? 2. Who makes his final appearance as M in Moonraker? 3. Which Bond character has diamonds embedded in his face? 4. In For Your Eyes Only, which recurring character does not appear for the first time in the series? 5. Who plays Solitaire in Live And Let Die? 6. Which character is painted gold in Goldfinger? 7. In Casino Royale, who is Solange married to? 8. In Skyfall, which character is told to “Think on your sins”? 9. Who plays Q in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service? 10. Name the character who is the head of the Japanese Secret Intelligence Service in You Only Live Twice? EMOJI FILM TITLES 1. 6. 2. 7. ∞ 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10. GUESS THE LOCATION 1. Who works here in Spectre? 3. Who lives on this island? 2. Which country is this lake in, as seen in Quantum Of Solace? 4. Patrice dies here in Skyfall. Name the city. GUESS THE LOCATION 5. Which iconic landmark is this? 7. Which country is this volcano situated in? 6. Where is James Bond’s family home? GUESS THE LOCATION 10. In which European country was this iconic 8. Bond and Anya first meet here, but which country is it? scene filmed? 9. In GoldenEye, Bond and Xenia Onatopp race their cars on the way to where? GENERAL KNOWLEDGE 1. In which Bond film did the iconic Aston Martin DB5 first appear? 2. -

MAESTROS DEL CINE CLÁSICO (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (En El 105 Aniversario De Su Nacimiento)

Cineclub Universitario / Aula de Cine P r o g r a m a c i ó n d e febrero 2 0 1 7 MAESTROS DEL CINE CLÁSICO (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (en el 105 aniversario de su nacimiento) Fotografía: Proyector “Marín” de 35mm (ca.1970). Cineclub Universitario Foto:Jacar [indiscreetlens.blogspot.com] (2015). El CINECLUB UNIVERSITARIO se crea en 1949 con el nombre de “Cineclub de Granada”. Será en 1953 cuando pase a llamarse con su actual denominación. Así pues en este curso 2016-2017, cumplimos 63 (67) años. FEBRERO 2017 MAESTROS DEL CINE CLÁSICO (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (en el 105 aniversario de su nacimiento) FEBRUARY 2017 MASTERS OF CLASSIC CINEMA (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (105 years since his birth) Viernes 3 / Friday 3th • 21 h. WHISKY A GOGÓ (1949) (WHISKY GALORE!) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 7 / Tuesday 7th • 21 h. EL HOMBRE VESTIDO DE BLANCO (1951) (THE MAN IN THE WHITE SUIT) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Viernes 10 / Friday 10th • 21 h. MANDY (1952) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 14 / Tuesday 14th • 21 h. EL QUINTETO DE LA MUERTE (1955) (THE LADYKILLERS) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Viernes 17 / Friday 17th • 21 h. CHANTAJE EN BROADWAY / EL DULCE SABOR DEL ÉXITO (1957) (SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 21 / Tuesday 21th • 21 h. SAMMY, HUIDA HACIA EL SUR (1963) (SAMMY GOING SOUTH) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Todas las proyecciones en la Sala Máxima de la ANTIGUA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA (Av. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

HATTIE JACQUES Born Josephine Edwina Jacques on February 7" 1922 She Went on to Become a Nationally Recognised Figure in the British Cinema of the 1950S and 60S

Hattie Jacaues Born 127 High St 1922 Chapter Twelve HATTIE JACQUES Born Josephine Edwina Jacques on February 7" 1922 she went on to become a nationally recognised figure in the British cinema of the 1950s and 60s. Her father, Robin Jacques was in the army and stationed at Shorncliffe Camp at the time of her birth. The Register of Electors shows the Jacques family residing at a house called Channel View in Sunnyside Road. (The register shows the name spelled as JAQUES, without the C. Whether Hattie changed the spelling or whether it was an error on the part of those who printed the register I don’t know) Hattie, as she was known, made her entrance into the world in the pleasant seaside village of Sandgate, mid way between Folkestone to the east and Hythe to the west. Initially Hattie trained as a hairdresser but as with many people of her generation the war caused her life to take a different course. Mandatory work saw Hattie first undertaking nursing duties and then working in North London as a welder Even in her twenties she was of a generous size and maybe as defence she honed her sense of humour after finding she had a talent for making people laugh. She first became involved in show business through her brother who had a job as the lift operator at the premises of the Little Theatre located then on the top floor of 43 Kings Street in Covent Garden. At end of the war the Little Theatre found itself in new premises under the railway arches below Charing Cross Station. -

September 6, 2011 (XXIII:2) Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard, PYGMALION (1938, 96 Min)

September 6, 2011 (XXIII:2) Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard, PYGMALION (1938, 96 min) Directed by Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard Written by George Bernard Shaw (play, scenario & dialogue), W.P. Lipscomb, Cecil Lewis, Ian Dalrymple (uncredited), Anatole de Grunwald (uncredited), Kay Walsh (uncredited) Produced by Gabriel Pascal Original Music by Arthur Honegger Cinematography by Harry Stradling Edited by David Lean Art Direction by John Bryan Costume Design by Ladislaw Czettel (as Professor L. Czettel), Schiaparelli (uncredited), Worth (uncredited) Music composed by William Axt Music conducted by Louis Levy Leslie Howard...Professor Henry Higgins Wendy Hiller...Eliza Doolittle Wilfrid Lawson...Alfred Doolittle Marie Lohr...Mrs. Higgins Scott Sunderland...Colonel George Pickering GEORGE BERNARD SHAW [from Wikipedia](26 July 1856 – 2 Jean Cadell...Mrs. Pearce November 1950) was an Irish playwright and a co-founder of the David Tree...Freddy Eynsford-Hill London School of Economics. Although his first profitable writing Everley Gregg...Mrs. Eynsford-Hill was music and literary criticism, in which capacity he wrote many Leueen MacGrath...Clara Eynsford Hill highly articulate pieces of journalism, his main talent was for Esme Percy...Count Aristid Karpathy drama, and he wrote more than 60 plays. Nearly all his writings address prevailing social problems, but have a vein of comedy Academy Award – 1939 – Best Screenplay which makes their stark themes more palatable. Shaw examined George Bernard Shaw, W.P. Lipscomb, Cecil Lewis, Ian Dalrymple education, marriage, religion, government, health care, and class privilege. ANTHONY ASQUITH (November 9, 1902, London, England, UK – He was most angered by what he perceived as the February 20, 1968, Marylebone, London, England, UK) directed 43 exploitation of the working class. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

The Deadly Price of Pursuing Peace by Evelyn Gordon

JANUARY 2010 ggggggggg The Deadly Price of Pursuing Peace by evelyn gordon WHEN the Oslo process began in 1993, one benefi t its adherents promised was a signifi cant improvement in Israel’s international standing. Now, 16 years later, Israel’s has fallen to an unprecedented low. Yet even today, conventional wisdom, including OBAMA’S NEXT THREE YEARS in Israel, continues to assert that Israel’s JOHN R. BOLTON #3 Commentary international standing depends on its A NEVER-ENDING willingness to advance the “peace pro- ECONOMIC CRISIS? DAVID M. SMICK cess.” So why has Israel’s standing fallen #3 WHY JEWS JANUARY 2010 : VOLUME 129 NUMBER 1 : VOLUME 2010 JANUARY so precipitously despite its numerous HATE PALIN JENNIFER RUBIN concessions for peace since 1993? The #3 PHILIP ROTH mounting evidence makes it inescapable: COMES TO THE END Israel’s standing has declined so precipi- SAM SACKS tously not despite Oslo but because of Oslo. $5.95 US : $7.00 CANADA $7.00 : US $5.95 JCC Maccabi Games 2009 Taube Koret Campus for Jewish Life KORET FOUNDATION AND TAUBE PHILANTHROPIES Collaborating to support Jewish life in the San Francisco Bay Area: Bay Area Jewish Community Centers Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco Hillel at Stanford JCC Maccabi Games 2009 Jewish Chaplaincy at Stanford University Medical Center Jewish Family & Children’s Services of San Francisco Jewish Home of San Francisco Koret-Taube Initiative on Jewish Peoplehood Taube Center for Jewish Studies at Stanford Taube Koret Campus for Jewish Life, Palo Alto Koret-Taube Grand Lobby, www.koretfoundation.org -

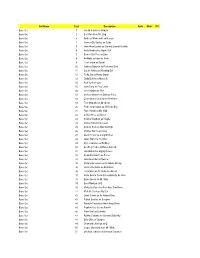

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'D Base Set 1 Harold Sakata As Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk As Mr

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'d Base Set 1 Harold Sakata as Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk as Mr. Ling Base Set 3 Andreas Wisniewski as Necros Base Set 4 Carmen Du Sautoy as Saida Base Set 5 John Rhys-Davies as General Leonid Pushkin Base Set 6 Andy Bradford as Agent 009 Base Set 7 Benicio Del Toro as Dario Base Set 8 Art Malik as Kamran Shah Base Set 9 Lola Larson as Bambi Base Set 10 Anthony Dawson as Professor Dent Base Set 11 Carole Ashby as Whistling Girl Base Set 12 Ricky Jay as Henry Gupta Base Set 13 Emily Bolton as Manuela Base Set 14 Rick Yune as Zao Base Set 15 John Terry as Felix Leiter Base Set 16 Joie Vejjajiva as Cha Base Set 17 Michael Madsen as Damian Falco Base Set 18 Colin Salmon as Charles Robinson Base Set 19 Teru Shimada as Mr. Osato Base Set 20 Pedro Armendariz as Ali Kerim Bey Base Set 21 Putter Smith as Mr. Kidd Base Set 22 Clifford Price as Bullion Base Set 23 Kristina Wayborn as Magda Base Set 24 Marne Maitland as Lazar Base Set 25 Andrew Scott as Max Denbigh Base Set 26 Charles Dance as Claus Base Set 27 Glenn Foster as Craig Mitchell Base Set 28 Julius Harris as Tee Hee Base Set 29 Marc Lawrence as Rodney Base Set 30 Geoffrey Holder as Baron Samedi Base Set 31 Lisa Guiraut as Gypsy Dancer Base Set 32 Alejandro Bracho as Perez Base Set 33 John Kitzmiller as Quarrel Base Set 34 Marguerite Lewars as Annabele Chung Base Set 35 Herve Villechaize as Nick Nack Base Set 36 Lois Chiles as Dr. -

David Hare's the Blue Room and Stanley

Schnitzler as a Space of Central European Cultural Identity: David Hare’s The Blue Room and Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut SUSAN INGRAM e status of Arthur Schnitzler’s works as representative of fin de siècle Vien- nese culture was already firmly established in the author’s own lifetime, as the tributes written in on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday demonstrate. Addressing Schnitzler directly, Hermann Bahr wrote: “As no other among us, your graceful touch captured the last fascination of the waning of Vi- enna, you were the doctor at its deathbed, you loved it more than anyone else among us because you already knew there was no more hope” (); Egon Friedell opined that Schnitzler had “created a kind of topography of the constitution of the Viennese soul around , on which one will later be able to more reliably, more precisely and more richly orient oneself than on the most obese cultural historian” (); and Stefan Zweig noted that: [T]he unforgettable characters, whom he created and whom one still could see daily on the streets, in the theaters, and in the salons of Vienna on the occasion of his fiftieth birthday, even yesterday… have suddenly disappeared, have changed. … Everything that once was this turn-of-the-century Vienna, this Austria before its collapse, will at one point… only be properly seen through Arthur Schnitzler, will only be called by their proper name by drawing on his works. () With the passing of time, the scope of Schnitzler’s representativeness has broadened. In his introduction to the new English translation of Schnitzler’s Dream Story (), Frederic Raphael sees Schnitzler not only as a Viennese writer; rather “Schnitzler belongs inextricably to mittel-Europa” (xii).