Evolving Reception and Canon Formation Through Sweet Smell of Success APPROVED by SUPERVISING COMMITTEE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Pulling focus: New perspectives on the work of Gabriel Figueroa Higgins, Ceridwen Rhiannon How to cite: Higgins, Ceridwen Rhiannon (2007) Pulling focus: New perspectives on the work of Gabriel Figueroa, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/2579/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Pulling Focus: New Perspectives on the Work of Gabriel Figueroa by Ceridwen Rhiannon Higgins University of Durham 2007 Submitted for Examination for Degree of PhD 1 1 JUN 2007 Abstract This thesis examines the work of Mexican cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa (1907 -1997) and suggests new critical perspectives on his films and the contexts within which they were made. Despite intense debate over a number of years, auteurist notions in film studies persist and critical attention continues to centre on the director as the sole giver of meaning to a film. -

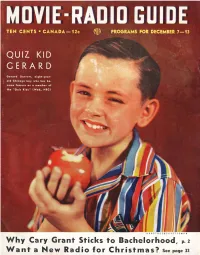

MOVIE · RADIO GUIDE: the National Weekly of Personalities and Programs

Why Cary Grant Sticks to Bachelorhood, p.2 Wan taN e vi R a d i 0 for C h r i s t 111 as? See page 33 MOVIE · RADIO GUIDE: The National Weekly of Personalities and Programs This Is Indeed the Golden .Age of Music WE A RE indebted to Viva liebling, our mu sic to find new songs and develop new song-writers editor, for call ing our attention to th e un and make new arrangements of all t he old tu nes pa ra lleled number of fine music programs now for which the copyrights had expired. All thar avai lable to listeners. O ne look at our renewed 8MI has b83n doi ng very success ful ly. " March of Music" departmen+ is abundant con Vv'h6t may happen soon is this : O n J anuary firm ation . Turn to page 14 noV! and see fOi I 'ihe networks may throw all ASCAP music off yo ursel f. the air. Th e networks want to pay for AS CAP Those names may mean little as yet, but read music by t he piece-so mu ch fo r every t i me it them through. The Cincinnati Symphony offers is used-which sounds fa ir enough to us. ASCAP "The Swan of Tuonela," "The Marriage of Fig wants a lump sum, a percentage of a ll t he money aro" comes from the Metropolitan Opera Com t,"lken in by a radio station . Righ t now, ASCAP pany, the NBC Symphony offers an all-Sibelius and the broadcasters aren't speaking. -

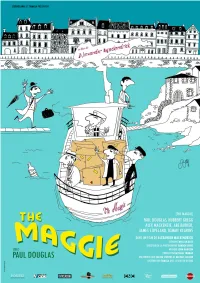

Maggie-Dp.Pdf

STUDIOCANAL et TAMASA présentent un film de Alexander Mackendrick ç Version restaurée UK - Durée 1h32 ç Sortie le 16 décembre 2015 ç Presse Frédérique Giezendanner [email protected] T. 06 10 37 16 00 Distribution TAMASA [email protected] T. 01 43 59 01 01 Visuels téléchargeables sur www.tamasadiffusion.com SYNOPSIS Le Capitaine de la « Maggie », Mac Taggart, ne possède pas suffisamment d’argent pour faire réparer son bateau qui tient la mer par miracle, malgré les réticences des autorités portuaires. Par suite d’un malentendu, Pusey, représentant un riche Américain, Marshall, lui confie le transport d’un matériel couteux destiné à la modernisation d’un château. Découvrant la supercherie, Marshall, atterré, essaye de récupérer son précieux chargement. Mais après bien des incidents, bien des événements inattendus avec ce curieux équipage, le chargement finira au fond de la mer. Mais Mac Taggart conserve l’argent que lui a remis Marshall pour faire réparer son vieux bateau. ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK Alexander Mackendrick est né à Boston, dans l’État du Massachusetts. À 6 ans, son père meurt emporté par la grippe « espagnole ». Sa mère, qui devait trouver du travail pour survivre, décide de devenir couturière. Elle céda la garde de son fils au grand-père qui vivait en Écosse. C’est ainsi qu’à l’âge de sept ans, Mackendrick revient sur la terre de ses aïeux. Il vit une enfance très solitaire et difficile. Après des études d’art, il part s’installer à Londres dans les années 30 pour travailler comme directeur artistique. Entre 1936 et 1938, Mackendrick est l’auteur du script de publicités cinématographiques. -

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

MAESTROS DEL CINE CLÁSICO (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (En El 105 Aniversario De Su Nacimiento)

Cineclub Universitario / Aula de Cine P r o g r a m a c i ó n d e febrero 2 0 1 7 MAESTROS DEL CINE CLÁSICO (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (en el 105 aniversario de su nacimiento) Fotografía: Proyector “Marín” de 35mm (ca.1970). Cineclub Universitario Foto:Jacar [indiscreetlens.blogspot.com] (2015). El CINECLUB UNIVERSITARIO se crea en 1949 con el nombre de “Cineclub de Granada”. Será en 1953 cuando pase a llamarse con su actual denominación. Así pues en este curso 2016-2017, cumplimos 63 (67) años. FEBRERO 2017 MAESTROS DEL CINE CLÁSICO (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (en el 105 aniversario de su nacimiento) FEBRUARY 2017 MASTERS OF CLASSIC CINEMA (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (105 years since his birth) Viernes 3 / Friday 3th • 21 h. WHISKY A GOGÓ (1949) (WHISKY GALORE!) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 7 / Tuesday 7th • 21 h. EL HOMBRE VESTIDO DE BLANCO (1951) (THE MAN IN THE WHITE SUIT) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Viernes 10 / Friday 10th • 21 h. MANDY (1952) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 14 / Tuesday 14th • 21 h. EL QUINTETO DE LA MUERTE (1955) (THE LADYKILLERS) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Viernes 17 / Friday 17th • 21 h. CHANTAJE EN BROADWAY / EL DULCE SABOR DEL ÉXITO (1957) (SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 21 / Tuesday 21th • 21 h. SAMMY, HUIDA HACIA EL SUR (1963) (SAMMY GOING SOUTH) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Todas las proyecciones en la Sala Máxima de la ANTIGUA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA (Av. -

SWEET SMELL of SUCCESS" Introducing SUSAN HARRISON a Norma-Curtle1gh Productions Picture Released Through United Artists

CAST AND CREDITS HECHT, HILL and LANCASTER Present BURT LANCASTER and TONY CURTIS In "SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS" Introducing SUSAN HARRISON A Norma-Curtle1gh Productions Picture Released through United Artists J. J. Hunsecker ••••••••••••..••••••• Burt LancaBter Sidney Falco••••••••••··•••·•••·•··· Tony Curtis Susan Hunsecker ····•·••···•••••••••• Susan Harrison Steve Dallas •••••••••••••••••••••••• Marty Milner Frank D'Angelo ••·••••••••••••••••··• Sam Levene Rita •••.•••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Barbara Nichols Sally . Jeff Dc>.nne11 Robard •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Joseph Leon Mary .••...••.•..•.••...••.••••••••.• Edith Atwater Harry Kello ••••••••••••••.•••••••••• Emile Meyer Herbie Temple•·••••••••·•••••••••••• Joe Frisco Otis Elwell •••••••••••.••••••••••••• David White Leo Bartha•••••••••••···•·•········· Lawrence Dobkin Mrs. Bartha • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • • • • • • • • • • • Lurene Tuttle Mildred Tam ••••••••••••••••••••••••. Queenie Smith Linda • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Autumn Russell Manny Davis······•····•••······••••• Jay Adler Al Evans • • • . • • . • • • • . • • • • • • • . • • • • • • • . Lewis Charles Produced by James Hill Directed by Alexander Mackendrick Screenplay by Clifford Odets and Ernest Lehman From the Novelette by Ernest Lehman Photography by James Wong Howe, A.s.c. Art Direction by Ed.ward Carrere Music Scored and Conducted by Elmer Bernstein S01 . .;s by Chico Hamilton and Fred Katz Running time: 103 minutee 11/6/ 56 l. Workin~ Script Por TIE S':iEET SNELL OF SUCCZSS FAD;: IN: 1 EXT. INT. GLOBE 1-fE':!SPAPER BUILDING - DUSK - N. Y. A r ow of newspaper delivery trucks is lined up aga1-nst the lo~~ loading bay, waiting for the edition. In the foreground a lai"ge clock establishe~ the time as 8! 10 PM. A rumbling noise war-ns the rr.en to take their positions; a few seconds lat e::'.' t he b~les of newspapers come sliding the spiral chutes on~o t~e mo·..r1n~ belts from which they are manhandled onto the tru~ks. Much !1o1se a:1d s!:.ou t ing. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project PETER KOVACH Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial Interview Date: April 18, 2012 Copyright 2015 ADST Q: Today is the 18th of April, 2012. Do you know ‘Twas the 18th of April in ‘75’? KOVACH: Hardly a man is now alive that remembers that famous day and year. I grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts. Q: We are talking about the ride of Paul Revere. KOVACH: I am a son of Massachusetts but the first born child of either side of my family born in the United States; and a son of Massachusetts. Q: Today again is 18 April, 2012. This is an interview with Peter Kovach. This is being done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and I am Charles Stuart Kennedy. You go by Peter? KOVACH: Peter is fine. Q: Let s start at the beginning. When and where were you born? KOVACH: I was born in Worcester, Massachusetts three days after World War II ended, August the 18th, 1945. Q: Let s talk about on your father s side first. What do you know about the Kovaches? KOVACH: The Kovaches are a typically mixed Hapsburg family; some from Slovakia, some from Hungary, some from Austria, some from Northern Germany and probably some from what is now western Romania. Predominantly Jewish in background though not practice with some Catholic intermarriage and Muslim conversion. Q: Let s take grandfather on the Kovach side. Where did he come from? KOVACH: He was born I think in 1873 or so. -

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present A film by Craig McCall Worldwide Sales: High Point Media Group Contact in Cannes: Residences du Grand Hotel, Cormoran II, 3 rd Floor: Tel: +33 (0) 4 93 38 05 87 London Contact: Tel: +44 20 7424 6870. Fax +44 20 7435 3281 [email protected] CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 1 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff www.jackcardiff.com Contents: - Film Synopsis p 3 - 10 Facts About Jack p 4 - Jack Cardiff Filmography p 5 - Quotes about Jack p 6 - Director’s Notes p 7 - Interviewee’s p 8 - Bio’s of Key Crew p10 - Director's Q&A p14 - Credits p 19 CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 2 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN : The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff A Documentary Feature Film Logline: Celebrating the remarkable nine decade career of legendary cinematographer, Jack Cardiff, who provided the canvas for classics like The Red Shoes and The African Queen . Short Synopsis: Jack Cardiff’s career spanned an incredible nine of moving picture’s first ten decades and his work behind the camera altered the look of films forever through his use of Technicolor photography. Craig McCall’s passionate film about the legendary cinematographer reveals a unique figure in British and international cinema. Long Synopsis: Cameraman illuminates a unique figure in British and international cinema, Jack Cardiff, a man whose life and career are inextricably interwoven with the history of cinema spanning nine decades of moving pictures' ten. -

Piraten- Und Seefahrerfilm 2011

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Matthias Christen; Hans Jürgen Wulff; Lars Penning Piraten- und Seefahrerfilm 2011 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12750 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Christen, Matthias; Wulff, Hans Jürgen; Penning, Lars: Piraten- und Seefahrerfilm. Hamburg: Universität Hamburg, Institut für Germanistik 2011 (Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 120). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12750. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0120_11.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Piraten- und Seefahrerfilme // Medienwissenschaft/Hamburg 120, 2011 /// 1 Medienwissenschaft / Hamburg: Berichte und Papiere 120, 2011: Piraten- und Seefahrerfilm. Redaktion und Copyright dieser Ausgabe: Matthias Christen, Hans J. Wulff, Lars Penning. ISSN 1613-7477. URL: http://www.rrz.uni-hamburg.de/Medien/berichte/arbeiten/0120_11.html Letzte Änderung: 28.4.2011. Piratenfilm: Ein Dossier gentlichen Piraten trennen, die „gegen alle Flaggen“ segelten und auf eigene Rechnung Beute machten. Inhalt: Zur Einführung: Die Motivwelt des Piratenfilms / Matthi- Selbst wenn die Helden und die sehr seltenen Hel- as Christen. dinnen die Namen authentischer Piraten wie Henry Piratenfilm: Eine Biblio-Filmographie. / Hans J. Wulff. Morgan, Edward Teach oder Anne Bonny tragen und 1. Bibliographie. 2. Filmographie der Piratenfilme. ihre Geschichte sich streckenweise an verbürgte Tat- Filmographie der Seefahrerfilme / Historische Segelschif- sachen hält, haben Piratenfilme jedoch weniger mit fahrtsfilme / Lars Penning. -

![Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3954/inmedia-3-2013-%C2%AB-cinema-and-marketing-%C2%BB-online-online-since-22-april-2013-connection-on-22-september-2020-603954.webp)

Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 3 | 2013 Cinema and Marketing Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.524 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference InMedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online since 22 April 2013, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ inmedia.524 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © InMedia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cinema and Marketing When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Nathalie Dupont and Joël Augros Jerry Pickman: “The Picture Worked.” Reminiscences of a Hollywood publicist Sheldon Hall “To prevent the present heat from dissipating”: Stanley Kubrick and the Marketing of Dr. Strangelove (1964) Peter Krämer Targeting American Women: Movie Marketing, Genre History, and the Hollywood Women- in-Danger Film Richard Nowell Marketing Films to the American Conservative Christians: The Case of The Chronicles of Narnia Nathalie Dupont “Paris . As You’ve Never Seen It Before!!!”: The Promotion of Hollywood Foreign Productions in the Postwar Era Daniel Steinhart The Multiple Facets of Enter the Dragon (Robert Clouse, 1973) Pierre-François Peirano Woody Allen’s French Marketing: Everyone Says Je l’aime, Or Do They? Frédérique Brisset Varia Images of the Protestants in Northern Ireland: A Cinematic Deficit or an Exclusive -

The Making of Hollywood Production: Televising and Visualizing Global Filmmaking in 1960S Promotional Featurettes

The Making of Hollywood Production: Televising and Visualizing Global Filmmaking in 1960s Promotional Featurettes by DANIEL STEINHART Abstract: Before making-of documentaries became a regular part of home-video special features, 1960s promotional featurettes brought the public a behind-the-scenes look at Hollywood’s production process. Based on historical evidence, this article explores the changes in Hollywood promotions when studios broadcasted these featurettes on television to market theatrical films and contracted out promotional campaigns to boutique advertising agencies. The making-of form matured in the 1960s as featurettes helped solidify some enduring conventions about the portrayal of filmmaking. Ultimately, featurettes serve as important paratexts for understanding how Hollywood’s global production work was promoted during a time of industry transition. aking-of documentaries have long made Hollywood’s flm production pro- cess visible to the public. Before becoming a staple of DVD and Blu-ray spe- M cial features, early forms of making-ofs gave audiences a view of the inner workings of Hollywood flmmaking and movie companies. Shortly after its formation, 20th Century-Fox produced in 1936 a flmed studio tour that exhibited the company’s diferent departments on the studio lot, a key feature of Hollywood’s detailed division of labor. Even as studio-tour short subjects became less common because of the restructuring of studio operations after the 1948 antitrust Paramount Case, long-form trailers still conveyed behind-the-scenes information. In a trailer for The Ten Commandments (1956), director Cecil B. DeMille speaks from a library set and discusses the importance of foreign location shooting, recounting how he shot the flm in the actual Egyptian locales where Moses once walked (see Figure 1). -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor.