•••

Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Recommended publications

-

Julia, Imagen Givenchy Su Esposo La Asesinó Caída De

EXCELSIOR MIÉRCOLES 10 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2014 [email protected] Resumen. Pharrell Williams encabeza la lista de @Funcion_Exc popularidad de Billboard. Y los escándalos del año>6 y 13 MAÑANA SE ESTRENA EN DOS MIL 400 SALAS UNA ÚLTIMA Los actores queAVENTURA participaron en El Hobbit: La batalla de los cinco ejércitos mostraron su satisfacción de poder participar en la tercera entrega de la saga dirigida por Peter Jackson >8 y 9 Fotos: Cortesía Warner Bros. Foto: Tomada de Instagram Givenchy Foto: Tomada de YouTube Foto: AP JULIA, IMAGEN GIVENCHY CAÍDA DE ELTON, VIRAL SU ESPOSO LA ASESINÓ PARÍS.- La actriz estadunidense Julia Roberts será la Más de un millón de visitas en sólo 24 horas alcanzó La actriz y modelo Stephanie Moseley, protagonista del nueva imagen de la casa francesa de moda Givenchy el video en el que se ve al cantante Elton John en una reality televisivo Hit The Floor, fue asesinada a tiros por para su campaña de primavera/verano 2015. aparatosa caída al presenciar un partido de tenis. Earl Hayes, quien era su esposo. El hombre se quitó la En las imágenes en blanco y negro, la actriz mues- El músico de 67 años asistió a un evento en el vida después de haberla matado. tra un aspecto andrógino, ataviada con una blusa ne- Royal Albert Hall de Londres, donde alentaba a su Trascendió que se habían separado hace dos años, gra con mangas transparentes. equipo contra el de la exjugadora profesional Billie Jean luego de un supuesto amorío con el músico Trey Songz, La sesión fue realizada por la importante empresa King, pero al intentar sentarse se suscitó el incidente. -

Toland Asc Digital Assistant

TOLAND ASC DIGITAL ASSISTANT PAINTING WITH LIGHT or more than 70 years, the American Cinematographer Manual has been the key technical resource for cinematographers around the world. Chemical Wed- ding is proud to be partners with the American Society of Cinematographers in bringing you Toland ASC Digital Assistant for the iPhone or iPod Touch. FCinematography is a strange and wonderful craft that combines cutting-edge technology, skill and the management of both time and personnel. Its practitioners “paint” with light whilst juggling some pretty challenging logistics. We think it fitting to dedicate this application to Gregg Toland, ASC, whose work on such classic films as Citizen Kane revolutionized the craft of cinematography. While not every aspect of the ASC Manual is included in Toland, it is designed to give solutions to most of cinematography’s technical challenges. This application is not meant to replace the ASC Manual, but rather serve as a companion to it. We strongly encourage you to refer to the manual for a rich and complete understanding of cin- ematography techniques. The formulae that are the backbone of this application can be found within the ASC Manual. The camera and lens data have largely been taken from manufacturers’ speci- fications and field-tested where possible. While every effort has been made to perfect this application, Chemical Wedding and the ASC offer Toland on an “as is” basis; we cannot guarantee that Toland will be infallible. That said, Toland has been rigorously tested by some extremely exacting individuals and we are confident of its accuracy. Since many issues related to cinematography are highly subjective, especially with re- gard to Depth of Field and HMI “flicker” speeds, the results Toland provides are based upon idealized scenarios. -

The Only Defense Is Excess: Translating and Surpassing Hollywood’S Conventions to Establish a Relevant Mexican Cinema”*

ANAGRAMAS - UNIVERSIDAD DE MEDELLIN “The Only Defense is Excess: Translating and Surpassing Hollywood’s Conventions to Establish a Relevant Mexican Cinema”* Paula Barreiro Posada** Recibido: 27 de enero de 2011 Aprobado: 4 de marzo de 2011 Abstract Mexico is one of the countries which has adapted American cinematographic genres with success and productivity. This country has seen in Hollywood an effective structure for approaching the audience. With the purpose of approaching national and international audiences, Meximo has not only adopted some of Hollywood cinematographic genres, but it has also combined them with Mexican genres such as “Cabaretera” in order to reflect its social context and national identity. The Melodrama and the Film Noir were two of the Hollywood genres which exercised a stronger influence on the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema. Influence of these genres is specifically evident in style and narrative of the film Aventurera (1949). This film shows the links between Hollywood and Mexican cinema, displaying how some Hollywood conventions were translated and reformed in order to create its own Mexican Cinema. Most countries intending to create their own cinema have to face Hollywood influence. This industry has always been seen as a leading industry in technology, innovation, and economic capacity, and as the Nemesis of local cinema. This case study on Aventurera shows that Mexican cinema reached progress until exceeding conventions of cinematographic genres taken from Hollywood, creating stories which went beyond the local interest. Key words: cinematographic genres, melodrama, film noir, Mexican cinema, cabaretera. * La presente investigación fue desarrollada como tesis de grado para la maestría en Media Arts que completé en el 2010 en la Universidad de Arizona, Estados Unidos. -

Pilot Season

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College Spring 2014 Pilot Season Kelly Cousineau Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cousineau, Kelly, "Pilot Season" (2014). University Honors Theses. Paper 43. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.77 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Pilot Season by Kelly Cousineau An undergraduate honorsrequirements thesis submitted for the degree in partial of fulfillment of the Bachelor of Arts in University Honors and Film Thesis Adviser William Tate Portland State University 2014 Abstract In the 1930s, two historical figures pioneered the cinematic movement into color technology and theory: Technicolor CEO Herbert Kalmus and Color Director Natalie Kalmus. Through strict licensing policies and creative branding, the husband-and-wife duo led Technicolor in the aesthetic revolution of colorizing Hollywood. However, Technicolor's enormous success, beginning in 1938 with The Wizard of Oz, followed decades of duress on the company. Studios had been reluctant to adopt color due to its high costs and Natalie's commanding presence on set represented a threat to those within the industry who demanded creative license. The discrimination that Natalie faced, while undoubtedly linked to her gender, was more systemically linked to her symbolic representation of Technicolor itself and its transformation of the industry from one based on black-and-white photography to a highly sanctioned world of color photography. -

Nostalgia for El Indio

FILMS NOSTALGIA FOR EL INDIO Fernando Fuentes This biography of Emilio Fernández, pacity creates a clear photographic Origins, Revolutions, Emigration one of Mexico's most famous film di- identity whether he portrays the Me- rectors of the so-called Golden Age of xican countryside or the urban scene. Emilio Fernández, known in the film Mexican film, was written with the All the solemn moments in his world as El Indio, was born in what is analytic professionalism and historic films are impregnated by a nostalgia now a ghost town but was part of a vision characteristic of Emilio García for the Revolution on the nationalist mining zone called Mineral de Hon- Riera. level, and by nostalgia for virginity do, in the municipality of Sabinas, In his detailed revision of El Indio on an emotional level, whether the Coahuila. He was the only child of Fernández' cinematographic work, film is set in the violence of the pro- Sara Romo, a Kikapoo Indian, and the author provides a critical evalu- vinces or in urban cabarets or bur- of Emilio Fernández Garza. ation of the film maker's produc- dels. The rhythm of his stories is He participated in the Revolution tion, and generally refers exactly to marked by impulses of a energetic as a boy, or at least, he dedicated his sources, be these material from sensibility and an admirable artistic himself to taking mental photos: "I newspapers, magazines or books, or capacity. had what all boys dream about: a pis- testimonies of those who lived or El Indio Fernández is a poet of tol, a horse and a battleground. -

"El Indio" Fernández: Myth, Mestizaje, and Modern Mexico

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2009-08-10 The Indigenismo of Emilio "El Indio" Fernández: Myth, Mestizaje, and Modern Mexico Mathew J. K. HILL Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation HILL, Mathew J. K., "The Indigenismo of Emilio "El Indio" Fernández: Myth, Mestizaje, and Modern Mexico" (2009). Theses and Dissertations. 1915. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1915 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE INDIGENISMO OF EMILIO “EL INDIO” FERNÁNDEZ: MYTH, MESTIZAJE, AND MODERN MEXICO by Matthew JK Hill A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Spanish and Portuguese Brigham Young University December 2009 Copyright © 2009 Matthew JK Hill All Rights Reserved BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Matthew JK Hill This thesis has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. Date Douglas J. Weatherford, Chair Date Russell M. Cluff Date David Laraway BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY As chair of the candidate’s graduate committee, I have read the thesis of Matthew JK Hill in its final form and have found that (1) its format, citations, and bibliographical style are consistent and acceptable and fulfill university and department style requirements; (2) its illustrative materials including figures, tables, and charts are in place; and (3) the final manuscript is satisfactory to the graduate committee and is ready for submission to the university library. -

ASC History Timeline 1919-2019

American Society of Cinematographers Historical Timeline DRAFT 8/31/2018 Compiled by David E. Williams February, 1913 — The Cinema Camera Club of New York and the Static Camera Club of America in Hollywood are organized. Each consists of cinematographers who shared ideas about advancing the art and craft of moviemaking. By 1916, the two organizations exchange membership reciprocity. They both disband in February of 1918, after five years of struggle. January 8, 1919 — The American Society of Cinematographers is chartered by the state of California. Founded by 15 members, it is dedicated to “advancing the art through artistry and technological progress … to help perpetuate what has become the most important medium the world has known.” Members of the ASC subsequently play a seminal role in virtually every technological advance that has affects the art of telling stories with moving images. June 20, 1920 — The first documented appearance of the “ASC” credential for a cinematographer in a theatrical film’s titles is the silent western Sand, produced by and starring William S. Hart and shot by Joe August, ASC. November 1, 1920 — The first issue of American Cinematographer magazine is published. Volume One, #1, consists of four pages and mostly reports news and assignments of ASC members. It is published twice monthly. 1922 — Guided by ASC members, Kodak introduced panchromatic film, which “sees” all of the colors of the rainbow, and recorded images’ subtly nuanced shades of gray, ranging from the darkest black to the purest white. The Headless Horseman is the first motion picture shot with the new negative. The cinematographer is Ned Van Buren, ASC. -

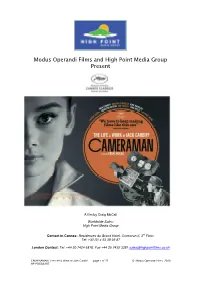

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present A film by Craig McCall Worldwide Sales: High Point Media Group Contact in Cannes: Residences du Grand Hotel, Cormoran II, 3 rd Floor: Tel: +33 (0) 4 93 38 05 87 London Contact: Tel: +44 20 7424 6870. Fax +44 20 7435 3281 [email protected] CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 1 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff www.jackcardiff.com Contents: - Film Synopsis p 3 - 10 Facts About Jack p 4 - Jack Cardiff Filmography p 5 - Quotes about Jack p 6 - Director’s Notes p 7 - Interviewee’s p 8 - Bio’s of Key Crew p10 - Director's Q&A p14 - Credits p 19 CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 2 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN : The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff A Documentary Feature Film Logline: Celebrating the remarkable nine decade career of legendary cinematographer, Jack Cardiff, who provided the canvas for classics like The Red Shoes and The African Queen . Short Synopsis: Jack Cardiff’s career spanned an incredible nine of moving picture’s first ten decades and his work behind the camera altered the look of films forever through his use of Technicolor photography. Craig McCall’s passionate film about the legendary cinematographer reveals a unique figure in British and international cinema. Long Synopsis: Cameraman illuminates a unique figure in British and international cinema, Jack Cardiff, a man whose life and career are inextricably interwoven with the history of cinema spanning nine decades of moving pictures' ten. -

Filmkatalog IAI Stand Februar 2015 Alph.Indd

KATALOG DER FILMSAMMLUNG Erwerbungen 2006 - 2014 CATÁLOGO DE LA COLECCIÓN DE CINE Adquisiciones 2006 - 2014 Inhalt Argentinien............................................................................. 4 Bolivien....................................................................................18 Brasilien...................................................................................18 Chile.........................................................................................31 Costa Rica................................................................................36 Cuba.........................................................................................36 Ecuador....................................................................................43 Guatemala...............................................................................46 Haiti.........................................................................................46 Kolumbien...............................................................................47 Mexiko.....................................................................................50 Nicaragua.................................................................................61 Peru.........................................................................................61 Spanien....................................................................................62 Uruguay...................................................................................63 Venezuela................................................................................69 -

Soco News 2018 09 V1

Institute of Amateur Cinematographers News and Views From Around The Region Nov - Dec 2018 Solent & Weymouth Anne Vincent has stepped down from Feel free to contact myself or other Laurie Joyce the position of the Southern Counties members of our committee. Region Chairman due to poor health but The new committee contacts are on will remain as a Honorary Member of the the last page of this magazine. Committee along with Phil Marshman who It brings me to say to you all in the also becomes an Honorary Member of the Region and further away A Very Happy Committee. Alan Christmas and a Happy New Year to you Wallbank I have been asked to stand as and your family Chairman which I duly accept and, along David Martin with my fellow Committee members, will help our region rise to the challenges of [email protected] Ian Simpson today! Frome Hello and welcome to another edition I have been a judge many times and Masha & of SoCo News. never had this hard a decision to make. Dasha The results of two competitions are Eventually, we placed Solent’s drama featured in this edition. There are a few “Someone To Watch Over Me” in second films that seem to be topping many of the place. This is a very well crafted Drama competitions. with exceptionally high standard of SoCo Comp It’s hardly surprising really, as they cinematography and direction. The main Results have been produced to a very high characters were well acted; to a standard standard. rarely seen in non professional films. -

Mayo 2017 Cine Dia a Dia

I PROGRAMACION MENSUAL MAYO 2017 CINE DIA A DIA LUNES 1 10:45 FZN Bandidas ACC 19:53 TNT La estafa maestra AVEN 06:00 SPC RPG: el juego más real 16:05 SPC Thor: un mundo oscuro 10:55 CNL Lluvia de hamburguesas INF 19:55 HBP Revancha DRA AVEN AVEN 00:00 WAR Si tuviera 30 COM 11:05 STU El lado oscuro de la justicia 20:00 STU Amor eterno DRA 06:09 TNT El plan B COM STU Soñando con el amor DRA 00:05 HBO La jefa COM SUS 20:10 CNL El último cazador de brujas 06:25 FZN Días de gloria DRA 16:30 HBO Sólo para parejas COM 00:11 TNT Thor: un mundo oscuro 11:38 CXO El mayordomo de la Casa CFICC 07:15 HBO Analízate COM 16:45 ISA Nena DRA AVEN Blanca BIO 20:25 FZN Con la frente en alto ACC 07:30 SPC Hulk CFIC 16:55 FZN Diez años después COM 00:25 STU Martes 13: parte II TERR 11:44 TNT 30 minutos ó menos ACC 21:45 CXO Quiero matar a mi jefe 2 07:40 CXO Oliver Twist DRA 17:35 HBP Un novato en apuros 2 COM 01:10 FZN FX II: Ilusiones mortales 11:55 SPC Hulk CFIC COM ISA The City of Your Final 17:39 CXO Línea de emergencia SUS CFIC 11:58 HBO Ant-Man: el hombre 22:00 CNL El redentor SUS Destination DRA TNT Los rompebodas COM HBP Escalofríos AVEN hormiga ACC FOX Proyecto almanaque CFIC 08:02 TNT La perla del dragón AVEN 17:45 WAR Los rompebodas COM 01:18 FOX Siete años en el Tíbet DRA 12:25 HBP La noche anterior COM FZN Karate Kid ACC 08:05 HBP Punto de quiebre ACC 18:00 FOX El Diablo viste a la moda 01:37 CXO Terror en Silent Hill SUS 12:30 CNL Bee Movie: la historia de HBO Ant-Man: el hombre 08:45 FOX Bob Esponja, la película INF COM STU Amor eterno DRA -

• ASC Archival Photos

ASC Archival Photos – All Captions Draft 8/31/2018 Affair in Trinidad - R. Hayworth (1952).jpg The film noir crime drama Affair in Trinidad (1952) — directed by Vincent Sherman and photographed by Joseph B. Walker, ASC — stars Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford and was promoted as a re-teaming of the stars of the prior hit Gilda (1946). Considered a “comeback” effort following Hayworth’s difficult marriage to Prince Aly Khan, Trinidad was the star's first picture in four years and Columbia Pictures wanted one of their finest cinematographers to shoot it. Here, Walker (on right, wearing fedora) and his crew set a shot on Hayworth over Ford’s shoulder. Dick Tracy – W. Beatty (1990).jpg Directed by and starring Warren Beatty, Dick Tracy (1990) was a faithful ode to the timeless detective comic strip. To that end, Beatty and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC — seen here setting a shot during production — rendered the film almost entirely in reds, yellows and blues to replicate the look of the comic. Storaro earned an Oscar nomination for his efforts. The two filmmakers had previously collaborated on the period drama Reds and later on the political comedy Bullworth. Cries and Whispers - L. Ullman (1974).jpg Swedish cinematographer Sven Nykvist, ASC operates the camera while executing a dolly shot on actress Liv Ullman, capturing an iconic moment in Cries and Whispers (1974), directed by friend and frequent collaborator Ingmar Bergman. “Motion picture photography doesn't have to look absolutely realistic,” Nykvist told American Cinematographer. “It can be beautiful and realistic at the same time.