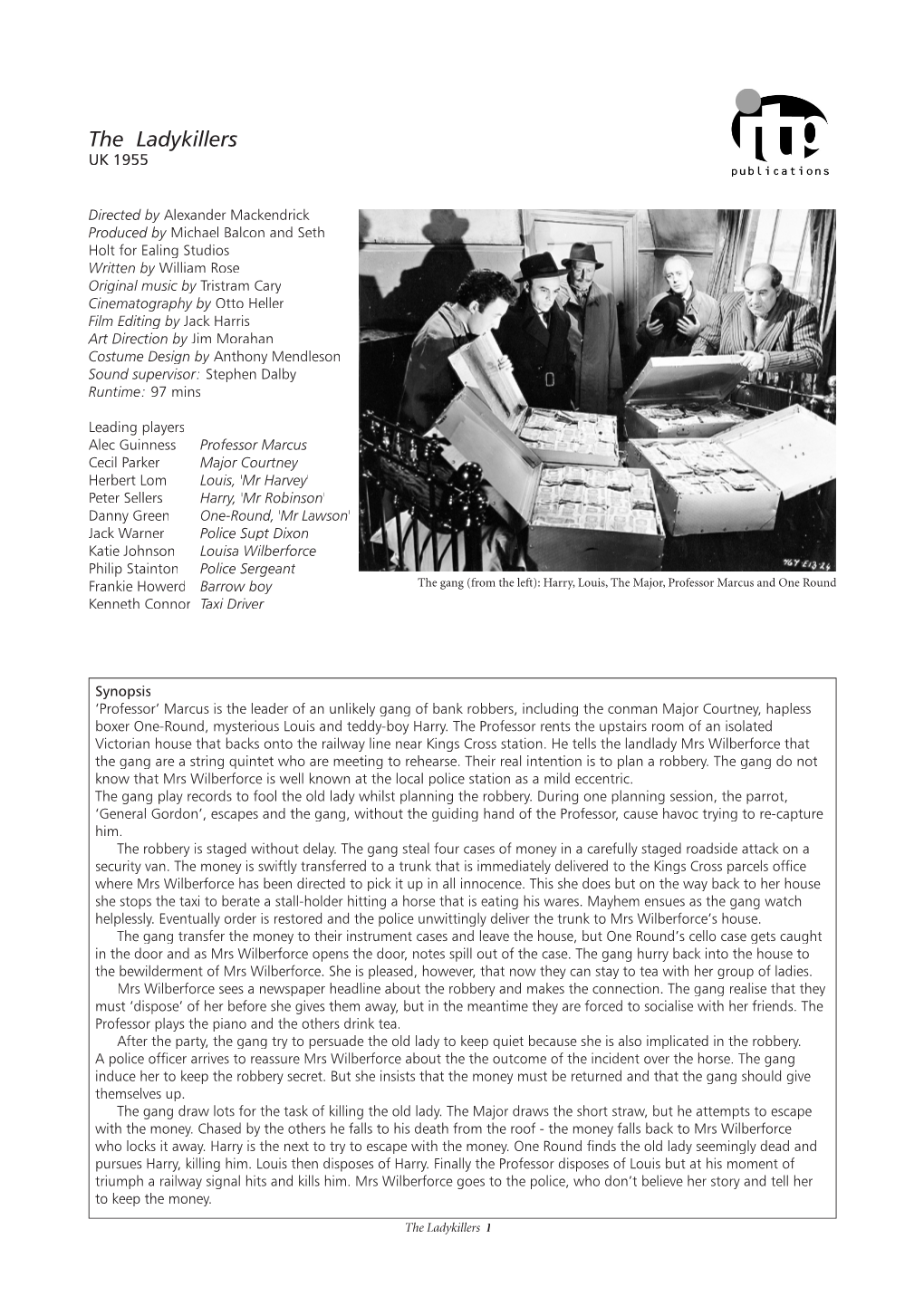

The Ladykillers UK 1955

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mini Brochure

filmworks is designed with star quality – inspired by the past, celebrating the future Ealing’s Thrilling New Lifestyle Quarter Computer-generated images are indicative only. Page 01 picture this IN TUNE WITH EALING’S HISTORY, THE STAR OF FILMWORKS WILL BE THE EIGHT-SCREEN PICTUREHOUSE CINEMA, TOGETHER WITH PLANET ORGANIC’S FRESH AND NATURAL PRODUCE. Eat well, live better, thanks to Planet Organic before heading to the movies. Filmworks offers an adventurous mix of shops, restaurants and bars; all perfectly located around a central and open piazza. PagePage 02 18 Lifestyle images are indicative only. Page 04 Computer-generated image is indicative only. Hollywood stars Audrey Hepburn, Humphrey Bogart and William Holden were a few of the big dazzling names to step foot in Ealing Studios. history THE FORUM CINEMA OPENED IN 1934 WITH ‘LIFE, LOVE AND LAUGHTER’. A COMEDY FILMED METRES AWAY, AT THE WORLD- FAMOUS EALING STUDIOS. The old cinema façade in 1963. Designed by John Stanley Beard, the old cinema’s classical colonnades create a grand entrance to the Filmworks quarter. Remarkably, the cinema building was relatively new compared to Ealing Studios, built in 1902. The first of its kind, with classics like The Ladykillers and recent successes The Theory of Everything and Downton Abbey, it is synonymous with the British film industry. Passport to Pimlico A 1949 British comedy starring Stanley Holloway in which a South London Street declares its independence. The Ladykillers A classic Ealing comedy starring Alec Guinness who becomes part of a ragtag criminal gang that runs into trouble when their landlady discovers there’s more to their string quartet than meets the eye. -

Maggie-Dp.Pdf

STUDIOCANAL et TAMASA présentent un film de Alexander Mackendrick ç Version restaurée UK - Durée 1h32 ç Sortie le 16 décembre 2015 ç Presse Frédérique Giezendanner [email protected] T. 06 10 37 16 00 Distribution TAMASA [email protected] T. 01 43 59 01 01 Visuels téléchargeables sur www.tamasadiffusion.com SYNOPSIS Le Capitaine de la « Maggie », Mac Taggart, ne possède pas suffisamment d’argent pour faire réparer son bateau qui tient la mer par miracle, malgré les réticences des autorités portuaires. Par suite d’un malentendu, Pusey, représentant un riche Américain, Marshall, lui confie le transport d’un matériel couteux destiné à la modernisation d’un château. Découvrant la supercherie, Marshall, atterré, essaye de récupérer son précieux chargement. Mais après bien des incidents, bien des événements inattendus avec ce curieux équipage, le chargement finira au fond de la mer. Mais Mac Taggart conserve l’argent que lui a remis Marshall pour faire réparer son vieux bateau. ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK Alexander Mackendrick est né à Boston, dans l’État du Massachusetts. À 6 ans, son père meurt emporté par la grippe « espagnole ». Sa mère, qui devait trouver du travail pour survivre, décide de devenir couturière. Elle céda la garde de son fils au grand-père qui vivait en Écosse. C’est ainsi qu’à l’âge de sept ans, Mackendrick revient sur la terre de ses aïeux. Il vit une enfance très solitaire et difficile. Après des études d’art, il part s’installer à Londres dans les années 30 pour travailler comme directeur artistique. Entre 1936 et 1938, Mackendrick est l’auteur du script de publicités cinématographiques. -

Darrol Blake Transcript

Interview with Darrol Blake by Dave Welsh on Tuesday the 21st of September 2010 Dave Welsh: Okay, this is an interview with Darrol Blake on Tuesday the 21st of September 2010, for the Britain at Work Project, West London, West Middlesex. Darrol, I wonder if you'd mind starting by saying how you got into this whole business. Darrol Blake: Well, I'd always wanted to be the man who made the shows, be it for theatre or film or whatever, and this I decided about the age of eleven or twelve I suppose, and at that time I happened to win a scholarship to grammar school, in West London, in Hanwell, and formed my own company within the school, I was in school plays and all that sort of thing, so my life revolved around putting on shows. Nobody in my family had ever been to university, so I assumed that when I got to sixteen I was going out to work. I didn't even assume I would go into the sixth form or anything. So when I did get to sixteen I wrote around to all the various places that I thought might employ me. Ealing Studios were going strong at that time, Harrow Coliseum had a rep. The theatre at home in Hayes closed on me. I applied for a job at Windsor Rep, and quite by the way applied to the BBC, and the only people who replied were the BBC, and they said we have vacancies for postroom boys, office messengers, and Radio Times clerks. -

MAESTROS DEL CINE CLÁSICO (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (En El 105 Aniversario De Su Nacimiento)

Cineclub Universitario / Aula de Cine P r o g r a m a c i ó n d e febrero 2 0 1 7 MAESTROS DEL CINE CLÁSICO (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (en el 105 aniversario de su nacimiento) Fotografía: Proyector “Marín” de 35mm (ca.1970). Cineclub Universitario Foto:Jacar [indiscreetlens.blogspot.com] (2015). El CINECLUB UNIVERSITARIO se crea en 1949 con el nombre de “Cineclub de Granada”. Será en 1953 cuando pase a llamarse con su actual denominación. Así pues en este curso 2016-2017, cumplimos 63 (67) años. FEBRERO 2017 MAESTROS DEL CINE CLÁSICO (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (en el 105 aniversario de su nacimiento) FEBRUARY 2017 MASTERS OF CLASSIC CINEMA (X): ALEXANDER MACKENDRICK (105 years since his birth) Viernes 3 / Friday 3th • 21 h. WHISKY A GOGÓ (1949) (WHISKY GALORE!) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 7 / Tuesday 7th • 21 h. EL HOMBRE VESTIDO DE BLANCO (1951) (THE MAN IN THE WHITE SUIT) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Viernes 10 / Friday 10th • 21 h. MANDY (1952) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 14 / Tuesday 14th • 21 h. EL QUINTETO DE LA MUERTE (1955) (THE LADYKILLERS) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Viernes 17 / Friday 17th • 21 h. CHANTAJE EN BROADWAY / EL DULCE SABOR DEL ÉXITO (1957) (SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Martes 21 / Tuesday 21th • 21 h. SAMMY, HUIDA HACIA EL SUR (1963) (SAMMY GOING SOUTH) v.o.s.e. / OV film with Spanish subtitles Todas las proyecciones en la Sala Máxima de la ANTIGUA FACULTAD DE MEDICINA (Av. -

A Dangerous Method

A David Cronenberg Film A DANGEROUS METHOD Starring Keira Knightley Viggo Mortensen Michael Fassbender Sarah Gadon and Vincent Cassel Directed by David Cronenberg Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Official Selection 2011 Venice Film Festival 2011 Toronto International Film Festival, Gala Presentation 2011 New York Film Festival, Gala Presentation www.adangerousmethodfilm.com 99min | Rated R | Release Date (NY & LA): 11/23/11 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Donna Daniels PR Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Donna Daniels Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone 77 Park Ave, #12A Jennifer Malone Lindsay Macik New York, NY 10016 Rebecca Fisher 550 Madison Ave 347-254-7054, ext 101 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 New York, NY 10022 Los Angeles, CA 90036 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 323-634-7030 fax A DANGEROUS METHOD Directed by David Cronenberg Produced by Jeremy Thomas Co-Produced by Marco Mehlitz Martin Katz Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Executive Producers Thomas Sterchi Matthias Zimmermann Karl Spoerri Stephan Mallmann Peter Watson Associate Producer Richard Mansell Tiana Alexandra-Silliphant Director of Photography Peter Suschitzky, ASC Edited by Ronald Sanders, CCE, ACE Production Designer James McAteer Costume Designer Denise Cronenberg Music Composed and Adapted by Howard Shore Supervising Sound Editors Wayne Griffin Michael O’Farrell Casting by Deirdre Bowen 2 CAST Sabina Spielrein Keira Knightley Sigmund Freud Viggo Mortensen Carl Jung Michael Fassbender Otto Gross Vincent Cassel Emma Jung Sarah Gadon Professor Eugen Bleuler André M. -

The Finance and Production of Independent Film and Television in the UK: a Critical Introduction

The Finance and Production of Independent Film and Television in the UK: A Critical Introduction Vital Statistics General Population: 64.1m Size: 241.9 km sq GDP: £1.9tr (€2.1tr) Film1 Market share of UK independent films in 2015: 10.5% Number of feature films produced: 201 Average visits to cinema per person per year: 2.7 Production spend per year: £1.4m (€1.6) TV2 Audience share of the main publicly-funded PSB (BBC): 72% Production spend by PSBs: £2.5bn (€3.2bn) Production spend by commercial channels (excluding sport): £350m (€387m) Time spent watching television per day: 193 minutes (3hrs 13 minutes) Introduction This chapter provides an overview of independent film and television production in the UK. Despite the unprecedented levels of convergence that characterise the digital era, the UK film and television industries remain distinct for several reasons. The film industry is small and fragmented, divided across the two opposing sources of support on which it depends: large but uncontrollable levels of ‘inward-investment’ – money invested in the UK from overseas – mainly from the US, and low levels of public subsidy. By comparison, the television industry is large and diverse, its relative stability underpinned by a long-standing infrastructure of 1 Sources: BFI 2016: 10; ‘The Box Office 2015’ [market share of UK indie films] ; BFI 2016: 6; ‘Exhibition’ [cinema visits per per person]; BFI 2016: 6; ‘Exhibition’ [average visits per person]; BFI 2016: 3; ‘Screen Sector Production’ [production spend per year]. 2 Sources: Oliver & Ohlbaum 2016: 68 [PSB audience share]; Ofcom 2015a: 3 [PSB production spend]; Ofcom 2015a: 8. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

Register of Entertainers, Actors and Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa

Register of Entertainers, Actors And Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1988_10 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Register of Entertainers, Actors And Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 11/88 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid Publisher United Nations, New York Date 1988-08-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1981 - 1988 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description INTRODUCTION. REGISTER OF ENTERTAINERS, ACTORS AND OTHERS WHO HAVE PERFORMED IN APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA SINCE JANUARY 1981. -

Goodnight Sweetheart" on BBC TV, Feb 5Th

THENORTH- WEST GEORGE FORMBY Newsletter 9 Volume 1, No.9 March 1996 Specially Produced for the North- West Branches of The George Formby Society by Stap Evans, The Hollies, 19 Hall Nook, Penketh, Warringtou Cheshire W A5 2HN Tel or Fax 01925 727102 2 \Velcome to Newsletter N-o.9 and what have we got this month? Well it's been hectic during February and some days the telephone has been Red-Hot! (Well not quite) In the centre pages we report the sale of George's family home in Warrington, "Hillcrest." The agents told the Newspapers that George was born there but, as we know, he wasn't. He was born at No.3 Westminster St, Wigan in 1904. He moved to Warrington around 1917. Although the roads have been blocked with .snow I am pleased that this hasn't prevented the members getting to the meetings. The highlight in February was the showing of "Goodnight Sweetheart" on BBC TV, Feb 5th. Leading up to the showing the phom ~ was busy again with members ringing to tell me that it was "all about George & Beryl." What a disappointment! It was an insult to George & Beryl and all Formby fans. After the showing, no less than 20 faxes went out to Newspapers and Radio Stations. Now Read All About It In TheN. West George Formby Newsletter. ***************** "Goodnight Sweetheart" BBC 1 TV 5th Feb. What a load of old RUBBISH. The BBC must be shoti of material to produce such tripe. Usually it is a good entertaining programme and each week the hero "has a go" at our George - which is acceptable as we don't expect everybody to be a Formby fan. -

The North of England in British Wartime Film, 1941 to 1946. Alan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CLoK The North of England in British Wartime Film, 1941 to 1946. Alan Hughes, University of Central Lancashire The North of England is a place-myth as much as a material reality. Conceptually it exists as the location where the economic, political, sociological, as well as climatological and geomorphological, phenomena particular to the region are reified into a set of socio-cultural qualities that serve to define it as different to conceptualisations of England and ‘Englishness’. Whilst the abstract nature of such a construction means that the geographical boundaries of the North are implicitly ill-defined, for ease of reference, and to maintain objectivity in defining individual texts as Northern films, this paper will adhere to the notion of a ‘seven county North’ (i.e. the pre-1974 counties of Cumberland, Westmorland, Northumberland, County Durham, Lancashire, Yorkshire, and Cheshire) that is increasingly being used as the geographical template for the North of England within social and cultural history.1 The British film industry in 1941 As 1940 drew to a close in Britain any memories of the phoney war of the spring of that year were likely to seem but distant recollections of a bygone age long dispersed by the brutal realities of the conflict. Outside of the immediate theatres of conflict the domestic industries that had catered for the demands of an increasingly affluent and consuming population were orientated towards the needs of a war economy as plant, machinery, and labour shifted into war production. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

Newsletter 55 Vol

THENORTH- WEST GEORGE FORMBY Newsletter 55 Vol. 5, No.7 January 2000 uuuuu~uuuuuuuu~uu rr · u u u u u _A_ 1-l u u u u u u u u u u u uuuuuuu~uuuuuuuuu Specially Produced for George Formby Fans by Stan Evans, The Hollies, 19 Hall Nook, Penketh, Warrington, Cheshire W A5 2HN Tel or Fax 01925 727102 -2- Welcome to Newsletter No.55 Well it's been a sad month with the loss of two dear members: Bill Pope of Liverpool and Denis Gale of the Sale branch Bill was a very keen Broad green player and a regular coach trip member. He enjoyed entertaining with his guitar and telling a few anecdotes or scouse jokes. He delighted the British Legion veterans in Caen last year and for the year 2000 he was ready to pay his deposit for the Eastbourne Trip before going into hospital with stomach cancer. Bill, who has organised many Music Hall Charity Shows over the years, had a lot of friends and relations and they aU turned up to show their respect at the St Pauls Church, West Derby, Liverpool on Thursday the 2nd of December. Bill was cremated. The large church was filled to capacity and later the huge band of Bill's admirers moved to the St Pauls Social Club where a buffet was laid on, followed by - at Maureen Pope's request - Cyril Palmer and Stan Evans singing Bill's favourite "Goodbye Dolly Gray." Denis Gale- A few days after Bill Pope's death I received deposits from Olwen and Denis Gale for the East bourne Trip, closely followed by a desperate phone call from · Olwen on Saturday morning the 27th December.