Sunrise Health Service Aboriginal Corporation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driving Holidays in the Northern Territory the Northern Territory Is the Ultimate Drive Holiday Destination

Driving holidays in the Northern Territory The Northern Territory is the ultimate drive holiday destination A driving holiday is one of the best ways to see the Northern Territory. Whether you are a keen adventurer longing for open road or you just want to take your time and tick off some of those bucket list items – the NT has something for everyone. Top things to include on a drive holiday to the NT Discover rich Aboriginal cultural experiences Try tantalizing local produce Contents and bush tucker infused cuisine Swim in outback waterholes and explore incredible waterfalls Short Drives (2 - 5 days) Check out one of the many quirky NT events A Waterfall hopping around Litchfield National Park 6 Follow one of the unique B Kakadu National Park Explorer 8 art trails in the NT C Visit Katherine and Nitmiluk National Park 10 Immerse in the extensive military D Alice Springs Explorer 12 history of the NT E Uluru and Kings Canyon Highlights 14 F Uluru and Kings Canyon – Red Centre Way 16 Long Drives (6+ days) G Victoria River region – Savannah Way 20 H Kakadu and Katherine – Nature’s Way 22 I Katherine and Arnhem – Arnhem Way 24 J Alice Springs, Tennant Creek and Katherine regions – Binns Track 26 K Alice Springs to Darwin – Explorers Way 28 Parks and reserves facilities and activities 32 Festivals and Events 2020 36 2 Sealed road Garig Gunak Barlu Unsealed road National Park 4WD road (Permit required) Tiwi Islands ARAFURA SEA Melville Island Bathurst VAN DIEMEN Cobourg Island Peninsula GULF Maningrida BEAGLE GULF Djukbinj National Park Milingimbi -

A Grammatical Sketch of Ngarla: a Language of Western Australia Torbjörn Westerlund

UPPSALA UNIVERSITY master thesis The department for linguistics and philology spring term 2007 A grammatical sketch of Ngarla: A language of Western Australia Torbjörn Westerlund Supervisor: Anju Saxena Abstract In this thesis the basic grammatical structure of normal speech style of the Western Australian language Ngarla is described using example sentences taken from the Ngarla – English Dictionary (by Geytenbeek; unpublished). No previous description of the language exists, and since there are only five people who still speak it, it is of utmost importance that it is investigated and described. The analysis in this thesis has been made by Torbjörn Westerlund, and the focus lies on the morphology of the nominal word class. The preliminary results show that the language shares many grammatical traits with other Australian languages, e.g. the ergative/absolutive case marking pattern. The language also appears to have an extensive verbal inflectional system, and many verbalisers. 2 Abbreviations 0 zero marked morpheme 1 first person 1DU first person dual 1PL first person plural 1SG first person singular 2 second person 2DU second person dual 2PL second person plural 2SG second person singular 3 third person 3DU third person dual 3PL third person plural 3SG third person singular A the transitive subject ABL ablative ACC accusative ALL/ALL2 allative ASP aspect marker BUFF buffer morpheme C consonant CAUS causative COM comitative DAT dative DEM demonstrative DU dual EMPH emphatic marker ERG ergative EXCL exclusive, excluding addressee FACT factitive FUT future tense HORT hortative ImmPAST immediate past IMP imperative INCHO inchoative INCL inclusive, including addressee INSTR instrumental LOC locative NEG negation NMLISER nominaliser NOM nominative N.SUFF nominal class suffix OBSCRD obscured perception P the transitive object p.c. -

2004 Edition 1 (PDF 2.5MB)

ORIG IN2004 EDITION 1 S Vice Chancellor’s comment Welcome to the first edition of Origins which profiles Australia’s newest university. Established in November 2003, Charles Darwin University is a place for fresh thought, bold vision and renewed focus. The first step has been to develop a new framework for the institution and we have been heartened by the support and input from our stakeholders in making sure we build the right framework to deliver outcomes for the Territory. The energy and enthusiasm that Charles Darwin University is harnessing in finding knowledge solutions is inspirational – and we have only just opened for business. With campuses and study centres located across the Northern Territory, we offer opportunities beyond what is normally expected of a University. We provide pathways into a broad range of courses in traditional areas as well as specialist areas unique to our location including tropical and desert studies and Indigenous research and education. For a place steeped in Aboriginal tradition and culture which enjoys a close interaction with the peoples of Southeast Asia, our location affords boundless research opportunities to create local knowledge with global applications. We are a University that dares to be different. We welcome researchers, teachers and students who are prepared to take on challenges and are committed to making a difference. This first edition of Origins provides a snapshot of the diversity and strengths on which we are building Vice Chancellor Professor Helen Garnett Vice Chancellor Professor the new institution. 1 Northern attraction Some of Australia’s leading academics have joined Charles Darwin University, strengthening the organisation’s role as a leading research and education provider in specialist areas. -

NLC Strategic Plan 2016-2020

NORTHERN LAND COUNCIL STRATEGIC PLAN 2016 – 2020 Strategic Plan 2016 – 2020 1. NORTHERN LAND COUNCIL STRATEGIC PLAN 2016 – 2020 About this strategic plan This Strategic Plan reflects the Northern Land Council’s strategic direction for the period 2016 – 2020. It builds on our achievements and describes the way we intend to carry out our statutory responsibilities, the goals we set out to achieve and our vision for the future. The Plan provides the framework for the continuing strategic management of our work. It is dynamic – reflecting the complex and changing environment in which we operate. We will revisit our strategies and projects regularly and continue to develop new initiatives, to ensure that we are able to respond to challenges and take advantage of opportunities as they arise. Contents Who we are .............................................................................................................. 1 What we do .............................................................................................................. 2 Welcome from the Chairman ................................................................................. 3 Introduction to the NLC from the CEO .................................................................. 4 Map of the NLC Region........................................................................................... 5 Communities in the NLC Region ........................................................................... 6 Our Vision ............................................................................................................... -

Inquiry Into Petrol Sniffing in Remote Aboriginal Communities

John Taylor is a Senior Fellow and Deputy Director at the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, The Australian National University. C entre for John Bern is a Professor and Director of the A boriginal South East Arnhem Land Collaborative E conomic Research Project (SEALCP) at the University of Wollongong. P olicy Kate Senior is an Honorary Fellow at SEALCP The Australian National University R esearch and a doctoral candidate at The Australian National University. Ngukurr at the Millennium at Ngukurr Rapid change arising from large-scale development projects can place severe strain on the physical infrastructure and Ngukurr at the social fabric of affected communities, as well as providing opportunities for betterment. The remote Aboriginal town of Ngukurr, together with its satellite outstations in the south- Millennium: A Baseline east Arnhem Land region of the Northern Territory, faces the J. Taylor, J. Bern, and K.A. Senior and K.A. Bern, J. Taylor, J. prospect of such change as a result of mineral exploration Profile for Social Impact activity currently underway, instigated by Rio Tinto. This study, which is comprehensive in its scope, provides a synchronistic baseline statistical analysis of social and Planning in South-East economic conditions in Ngukurr. It emphasises several key areas of policy interest and intervention, including the Arnhem Land demographic structure and residence patterns of the regional population, and their labour force status, education and training, income, welfare, housing, and health status. J. Taylor, J. Bern, and K.A. Senior The result is an appraisal of Ngukurr’s social and economic life after a generation of self management and land rights, immediatly prior to a possible period of major introduced economic development based on mineral exploitation. -

Guide to Sound Recordings Collected by Margaret C. Sharpe, 1966-1967

Finding aid SHARPE_M02 Sound recordings collected by Margaret C. Sharpe, 1966-1967 Prepared June 2011 by SL Last updated 19 December 2016 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by completing an online enquiry form or phone (02) 6261 4212 to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening This collection is open for listening. Restrictions on use Copies of this collection may be made for private research. Permission must be sought from the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1966-1967 Extent: 55 sound tapes : analogue, mono. Production history These recordings were collected between November 1965 and October 1967 by linguist Margaret Sharpe, an AIAS (now AIATSIS) grantee, while on fieldwork at Woodenbong in New South Wales, Woorabinda, Emerald and Brisbane in Queensland, and Ngukurr, Nutwood and Minyerri in the Northern Territory. The purpose of the field trips was to document the languages, stories and songs of the Indigenous peoples of these areas. The cultures which were investigated are Yugambeh and Bundjalung of northern NSW; Gangulu, Gooreng Gooreng, Mamu (Malanda dialect), Guugu Yimidhirr, Wakaya, Wangkumara, Kuungkari, Biri and Galali from Queensland; and Alawa, Mara, Ritharrngu, Warndarrang, Ngalakan, Yanyuwa, Mangarrayi and Gurdanji from the Northern Territory. The interviewees and performers include Joe Culham, Adrian [Eddie] Conway, Johnson Mate Mate, Willie Toolban, Henry Bloomfield, Victor Reid, Willie Healy, Fred Grogan, Nugget Swan, Ted Maranoa, Willie Rookwood, Rosie Williams, Barnabas Roberts, Bill Turnbull, Dan Cot, Bessie Farrell, Isaac Joshua, Norman, Ivy, Matthew, Caleb Roberts, Limmen Harry, Kellie, Kittie, Clancy Roberts, Francis, Viola Tiers and unidentified contributors. -

2 Sociohistorical Context

2 Sociohistorical context 2.1 Introduction This chapter presents sociohistorical data from the Roper River region from the 1840s to the 1960s. The aim of this chapter is to determine when and how a creole language evolved in the Roper River region and what role the pastoral industry may have played. Chapter 2 expands on Harris (1986), which is to date the most comprehensive sociohistorical study of pidgin and creole emergence in the Northern Territory. This work complemented Sandefur (1986) and provided background to other studies such as Munro (2000). Harris (1986) uses sociohistorical data from the 1840s-1900s from the early settlements in the vicinity of present day Darwin and the coastal regions in contact with the Macassans to describe the development and stabilisation of Northern Territory Pidgin (NT Pidgin) by the 1900s. Harris (1986) also describes the cattle industry invasion, as well as the establishment of the Roper River Mission (RRM), which led to the suggestion that abrupt creole genesis occurred in the RRM from 1908. The information in this chapter will contribute to the application of the Transfer Constraints approach to substrate transfer in Kriol in three ways. Firstly, it will provide evidence of which substrate languages had most potential for input in the process of transfer to the NT Pidgin, and ultimately then Kriol. Secondly, the sociohistorical data should suggest how much access to English, as the superstrate language, the substrate language speakers had. And finally, the description of each phase will allow for accurate identification of the timeframes within which transfer and levelling (as discussed in chapter 1) occurred. -

In Ngukurr: a Remote Australian Aboriginal Community

Understanding ‘Work’ in Ngukurr: A Remote Australian Aboriginal Community Eva McRae-Williams (BA, BBH, MA) September 2008 Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for: Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) Charles Darwin University Statement of Authorship Except where referenced in the text of the research project, this dissertation contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or part from a thesis or report by me for another degree or diploma. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the dissertation. The dissertation has not been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. Eva McRae-Williams Date: ……………… ii Abstract This thesis is an ethnographic study of the ‘work’ ideologies inherent in a remote Australian Aboriginal community; Ngukurr in South East Arnhem Land of the Northern Territory. Formerly known as the Roper River Mission and established in 1908, it is today home to approximately 1000 Aboriginal inhabitants. Fieldwork for this project was conducted in three phases between 2006 and 2007 totalling seven months. The aim of this research was to gain an insight into the meaning and value of ‘work’ for Aboriginal people in Ngukurr. First, this involved acknowledging the centrality of paid employment to mainstream western ‘work’ ideology and its influence on my own, and other non-Aboriginal peoples, understandings and ways of being in the world. Through this recognition the historical and contemporary relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in the northern part of Australia, specifically the Roper River region, was found to be fundamentally shaped by labour relations and dominant western ‘work’ ideology. -

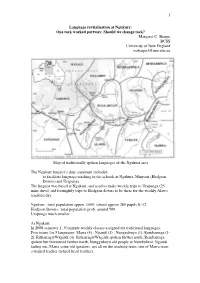

1 Language Revitalisation at Ngukurr: One Tack Worked Partway

1 Language revitalisation at Ngukurr: One tack worked partway: Should we change tack? Margaret C. Sharpe BCSS University of New England [email protected] Map of traditionally spoken languages of the Ngukurr area The Ngukurr linguist’s duty statement included: to facilitate language teaching in the schools at Ngukurr, Minyerri (Hodgson Downs) and Urapunga The linguist was based at Ngukurr, and used to make weekly trips to Urapunga (25 mins drive) and fortnightly trips to Hodgson downs to be there for the weekly Alawa teaching day. Ngukurr: total population appox. 1500; school approx 280 pupils K-12. Hodgson Downs: total population prob. around 500. Urapunga much smaller. At Ngukurr: In 2008 semester 1, 30 minute weekly classes assigned for traditional languages. Five teams for 5 languages: Marra (4) , Ngandi (1) , Nunggubuyu (1), Rembarrnga (1- 2), Ritharrngu/Wägilak (4). Ritharrngu/Wägilak spoken further north, Rembarrnga spoken but threatened further north, Nunggubuyu old people at Numbulwar, Ngandi fading out, Marra some old speakers, not all on the teaching team, one of Marra team a trained teacher (retired head teacher). 2 School language teaching for some years has been words in a chosen domain, and some songs: e.g. in Marra: Nga-jurra na-balba-yurr , na-balba-yurr, na-balba-yurr Nga-jurra na-balba-yurr, Jurr-nga-ju na-warlanyan-i I-went masc-river-to catch-I-did masc-fish-for Minyerri School: a trained local teacher in charge, not an Alawa speaker, 1-2 Alawa speakers, two non-speaking Alawa helpers. 30 minute lessons, but better organised than at Ngukurr because co-ordinated by a trained teacher. -

Gulf Water Study Roper River Region

Gulf Water Study Roper River Region Front cover: Painting of the Rainbow Serpent by Rex Wilfred. (see Appendix A for the story of the painting) Satellite image of the Roper River. Yawurrwarda Lagoon. GULF WATER STUDY Early morning at Roper Bar, Roper River WATER RESOURCES OF THE ROPER RIVER REGION REPORT 16/2009D U. ZAAR DARWIN NT © Northern Territory of Australia, 2009 ISBN 978-1-921519-64-2 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was co -funded through the Australian Government Water Smart Australia Program and the Northern Territory Government Department of Natural Resources, Environment the Arts and Sport. I would like to thank my colleagues who provided help on this project: Peter Jolly (now retired) who instigated this project; Des Yin Foo for his generous support as our team manager; Anthony Knapton, my co-worker on this project who provided technical and field assistance; Steve Tickell, Danuta Karp and Jon Sumner for their technical advice; Lynton Fritz for his outstanding cartographic skills in drawing up the maps; Renee Ramsay for the production of the GIS and collation of the DVD and our experienced technical team – Rodney Metcalfe, Steve Hester, Roger Farrow and Rob Chaffer for all their efficient fieldwork. A special thanks also to Phil O’Brien who not only provided enthusiastic field assistance but wise advice. I take pleasure in also thanking members of our technical working group; Max Gorringe - the manager of Elsey Station, Frank Shadforth – the manager of Seven Emu Station and Glenn Wightman – ethnobiologist who all kindly took the time to provide advice at our meetings. All were always ready to help. -

Guide to Sound Recordings Collected by David C. Biernoff, 1971-1972

Finding aid BIERNOFF_D01 Sound recordings collected by David C. Biernoff, 1971-1972 Prepared March 2010 by SL Last updated 9 November 2016 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by email to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening This collection is restricted and may only be listened to by those who have obtained written permission from the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community. Refer to audition sheets below for more details. Restrictions on use This collection is restricted and may only be copied by those who have obtained permission from David Biernoff. Permission must be sought from the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1971-1972 Extent: 19 sound cassettes (ca. 60 min. each) : analogue, mono + field tape report sheets. Production history These recordings were collected between 10 November 1971 and 7 September 1972 by David C. Biernoff during field work at Numbulwar in Eastern Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia. The purpose of the field trips was to research circumcision ceremonies, men's song cycles, the dhambul corroboree; Dreaming stories, relationship to country, sites, law, traditions, skin groups and traditional medical practices of the Nunggubuyu, Manggurra, Nargala, Madarrpa, Dhalwangu, Mara and Warndarrang peoples of the region about Numbulwar. Interviewees and performers include Lalbich, Larranggana, Tommy Reuben, Wurramarbi, Galiliwa, Rimili, Nambadj, Mongoana, Peter Yarrawu, Rex, Tommy, Homer, Wiyulwi, Don, Rruyilnga, Djima, Gumuk, Dunggi, Waguti Marawilli, Ken, Bob, Mac Riley, Lindsay Joshua and Alex. -

Our Land, Our Sea, Our Life

Our Land, Our Sea, Our Life ANNUAL REPORT 2017/18 Our Land, Our Sea, Our Life © Commonwealth of Australia 2018 ISSN 1030-522X With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms and where otherwise noted, all material presented in this document, the Northern Land Council Annual Report 2017/18, is provided under a Creative Commons Licence. The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website at creativecommons.org/licences/ by/3.0/au/, as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3 AU licence Red Flag Dancers perform at Ngukurr. NORTHERN LAND COUNCIL ANNUAL REPORT 2017/18 OUR VALUES ... OUR VISION … We will: is to have the land and sea rights of • Consult with and act with the informed Traditional Owners and affected Aboriginal consent of Traditional Owners in accordance people in the Top End of the Northern with the Aboriginal Land Rights Act. Territory recognised and to ensure that Aboriginal people benefit socially, • Communicate clearly with Aboriginal culturally and economically from the secure people, taking into account the possession of our land, waters and seas. linguistic diversity of the region. • Respect Aboriginal law and tradition. WE AIM TO… • Be responsive to Aboriginal peoples’ needs achieve enhanced social, political and and effectively advocate for their interests. economic participation and equity for Aboriginal people through the promotion, • Be accountable to the people we represent protection and advancement of our land • Behave in a manner that is appropriate rights and other rights and interests. and sensitive to cultural differences. • Act with integrity, honesty and fairness.