In Ngukurr: a Remote Australian Aboriginal Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driving Holidays in the Northern Territory the Northern Territory Is the Ultimate Drive Holiday Destination

Driving holidays in the Northern Territory The Northern Territory is the ultimate drive holiday destination A driving holiday is one of the best ways to see the Northern Territory. Whether you are a keen adventurer longing for open road or you just want to take your time and tick off some of those bucket list items – the NT has something for everyone. Top things to include on a drive holiday to the NT Discover rich Aboriginal cultural experiences Try tantalizing local produce Contents and bush tucker infused cuisine Swim in outback waterholes and explore incredible waterfalls Short Drives (2 - 5 days) Check out one of the many quirky NT events A Waterfall hopping around Litchfield National Park 6 Follow one of the unique B Kakadu National Park Explorer 8 art trails in the NT C Visit Katherine and Nitmiluk National Park 10 Immerse in the extensive military D Alice Springs Explorer 12 history of the NT E Uluru and Kings Canyon Highlights 14 F Uluru and Kings Canyon – Red Centre Way 16 Long Drives (6+ days) G Victoria River region – Savannah Way 20 H Kakadu and Katherine – Nature’s Way 22 I Katherine and Arnhem – Arnhem Way 24 J Alice Springs, Tennant Creek and Katherine regions – Binns Track 26 K Alice Springs to Darwin – Explorers Way 28 Parks and reserves facilities and activities 32 Festivals and Events 2020 36 2 Sealed road Garig Gunak Barlu Unsealed road National Park 4WD road (Permit required) Tiwi Islands ARAFURA SEA Melville Island Bathurst VAN DIEMEN Cobourg Island Peninsula GULF Maningrida BEAGLE GULF Djukbinj National Park Milingimbi -

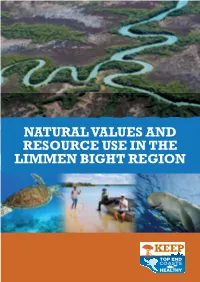

Natural Values and Resource Use in the Limmen Bight

NATURAL VALUES AND RESOURCE USE IN THE LIMMEN BIGHT REGION © Australian Marine Conservation Society, January 2019 Australian Marine Conservation Society Phone: +61 (07) 3846 6777 Freecall: 1800 066 299 Email: [email protected] PO Box 5815 West End QLD 4101 Keep Top End Coasts Healthy Alliance Keep Top End Coasts Healthy is an alliance of environment groups including the Australian Marine Conservation Society, the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Environment Centre of the Northern Territory. Authors: Chris Smyth and Joel Turner, Centre for Conservation Geography Printing: Printed on 100% recycled paper by IMAGE OFFSET, Darwin. Maps: Centre for Conservation Geography This report is an independent research paper prepared by the Centre for Conservation Geography commissioned by, and for the exclusive use of, the Keep Top End Coasts Healthy (KTECH) alliance. The report must only be used by KTECH, or with the explicit permission of KTECH. The matters covered in the report are those agreed to between KTECH and the authors. The report does not purport to consider exhaustively all values of the Limmen Bight region. The authors do not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation, compensatory, direct, indirect, or consequential damages and claims of third parties that may be caused directly or indirectly through the use of, reliance upon or interpretation of the contents of the report. Cover photos: Main - Limmen River. Photo: David Hancock Inset (L-R): Green Turtle, Recreational fishing is an important leisure activity in -

Springs of the Mataranka Area 4

THE BIG PICTURE SPRINGS OF THE MATARANKA AREA 4. THE SWAMP Timor Sea A cavernous limestone aquifer extends The large swampy area located on the south side of across a large part of the Northern Territory the Roper River also owes it’s existence to a and into Queensland. The springs at The Mataranka area is notable for its many springs. geological structure that has caused the aquifer to DARWIN Mataranka are one of several outlet points for become shallower and to thin out towards the Roper the aquifer. Other big springs are found on 295000mE This map shows the location of the main springs and other groundwater discharge features. River (see the cross-section). This has resulted in a the Flora, Katherine and Daly Rivers and in broad area underlain by a shallow watertable and Queensland on the Lawn Hill Creek and It explains why the springs are there and describes some of their characteristics. zones of seepage. Extensive tufa deposits formed there because a ridge of bedrock located downstream Daly River Springs KATHERINE Gulf Gregory River. At Mataranka the water of originates from areas to the southeast as far of the seepage zone, ponded the water in a similar Flora River Springs MATARANKA Carpentaria away as the Barkly Tablelands and from the manner to the rock bars in streams as described in 300000mE northwest as far as the King River. Qa1 the note on tufa formation. The ridge formed a base for tufa to accumulate. Tufa dams merged and grew - Waterhouse Cmt over older ones, eventually forming a continuous sheet of limestone. -

Testudines: Chelidae) of Australia, New Guinea and Indonesia

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2002, 134, 401–421. With 7 figures Electrophoretic delineation of species boundaries within the genus Chelodina (Testudines: Chelidae) of Australia, New Guinea and Indonesia ARTHUR GEORGES1*, MARK ADAMS2 and WILLIAM McCORD3 1Applied Ecology Research Group, University of Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia 2Evolutionary Biology Unit, South Australian Museum, North Terrace, Adelaide, SA 5001, Australia 3East Fishkill Animal Hospital, 285 Rt 82, Hopewell Junction NY 12533, USA Received February 2001; revised and accepted for publication June 2001 A total of 281 specimens of long-necked chelid turtles (Chelodina) were obtained from drainages of Australia, Papua New Guinea and the island of Roti in Indonesia. Ten diagnosable taxa were identified using allozyme profiles at 45 presumptive loci. Chelodina expansa, C. parkeri, C. rugosa and C. burrungandjii are in a Group A clade, C. longi- collis, C. novaeguineae, C. steindachneri, C. pritchardi and C. mccordi are in a Group B clade, and C. oblonga is in a monotypic Group C clade, with each clade thought to represent a distinct subgenus. Chelodina siebenrocki is syn- onymised with C. rugosa. An eleventh taxon, C. reimanni, could not be distinguished from C. novaeguineae on the basis of allozyme profiles, but it is morphologically distinct. Its status is therefore worthy of further investigation. Three instances of natural hybridization were detected. Chelodina rugosa and C. novaeguineae hybridize in the Gulf country of Queensland, with evidence of backcrossing to C. novaeguineae. Chelodina longicollis and C. novaeguineae hybridize in central coastal Queensland, and C. rugosa and C. burrungandjii hybridize along their zone of contact in the plateau escarpment streams and pools. -

2004 Edition 1 (PDF 2.5MB)

ORIG IN2004 EDITION 1 S Vice Chancellor’s comment Welcome to the first edition of Origins which profiles Australia’s newest university. Established in November 2003, Charles Darwin University is a place for fresh thought, bold vision and renewed focus. The first step has been to develop a new framework for the institution and we have been heartened by the support and input from our stakeholders in making sure we build the right framework to deliver outcomes for the Territory. The energy and enthusiasm that Charles Darwin University is harnessing in finding knowledge solutions is inspirational – and we have only just opened for business. With campuses and study centres located across the Northern Territory, we offer opportunities beyond what is normally expected of a University. We provide pathways into a broad range of courses in traditional areas as well as specialist areas unique to our location including tropical and desert studies and Indigenous research and education. For a place steeped in Aboriginal tradition and culture which enjoys a close interaction with the peoples of Southeast Asia, our location affords boundless research opportunities to create local knowledge with global applications. We are a University that dares to be different. We welcome researchers, teachers and students who are prepared to take on challenges and are committed to making a difference. This first edition of Origins provides a snapshot of the diversity and strengths on which we are building Vice Chancellor Professor Helen Garnett Vice Chancellor Professor the new institution. 1 Northern attraction Some of Australia’s leading academics have joined Charles Darwin University, strengthening the organisation’s role as a leading research and education provider in specialist areas. -

NLC Strategic Plan 2016-2020

NORTHERN LAND COUNCIL STRATEGIC PLAN 2016 – 2020 Strategic Plan 2016 – 2020 1. NORTHERN LAND COUNCIL STRATEGIC PLAN 2016 – 2020 About this strategic plan This Strategic Plan reflects the Northern Land Council’s strategic direction for the period 2016 – 2020. It builds on our achievements and describes the way we intend to carry out our statutory responsibilities, the goals we set out to achieve and our vision for the future. The Plan provides the framework for the continuing strategic management of our work. It is dynamic – reflecting the complex and changing environment in which we operate. We will revisit our strategies and projects regularly and continue to develop new initiatives, to ensure that we are able to respond to challenges and take advantage of opportunities as they arise. Contents Who we are .............................................................................................................. 1 What we do .............................................................................................................. 2 Welcome from the Chairman ................................................................................. 3 Introduction to the NLC from the CEO .................................................................. 4 Map of the NLC Region........................................................................................... 5 Communities in the NLC Region ........................................................................... 6 Our Vision ............................................................................................................... -

Inquiry Into Petrol Sniffing in Remote Aboriginal Communities

John Taylor is a Senior Fellow and Deputy Director at the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, The Australian National University. C entre for John Bern is a Professor and Director of the A boriginal South East Arnhem Land Collaborative E conomic Research Project (SEALCP) at the University of Wollongong. P olicy Kate Senior is an Honorary Fellow at SEALCP The Australian National University R esearch and a doctoral candidate at The Australian National University. Ngukurr at the Millennium at Ngukurr Rapid change arising from large-scale development projects can place severe strain on the physical infrastructure and Ngukurr at the social fabric of affected communities, as well as providing opportunities for betterment. The remote Aboriginal town of Ngukurr, together with its satellite outstations in the south- Millennium: A Baseline east Arnhem Land region of the Northern Territory, faces the J. Taylor, J. Bern, and K.A. Senior and K.A. Bern, J. Taylor, J. prospect of such change as a result of mineral exploration Profile for Social Impact activity currently underway, instigated by Rio Tinto. This study, which is comprehensive in its scope, provides a synchronistic baseline statistical analysis of social and Planning in South-East economic conditions in Ngukurr. It emphasises several key areas of policy interest and intervention, including the Arnhem Land demographic structure and residence patterns of the regional population, and their labour force status, education and training, income, welfare, housing, and health status. J. Taylor, J. Bern, and K.A. Senior The result is an appraisal of Ngukurr’s social and economic life after a generation of self management and land rights, immediatly prior to a possible period of major introduced economic development based on mineral exploitation. -

Guide to Sound Recordings Collected by Margaret C. Sharpe, 1966-1967

Finding aid SHARPE_M02 Sound recordings collected by Margaret C. Sharpe, 1966-1967 Prepared June 2011 by SL Last updated 19 December 2016 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by completing an online enquiry form or phone (02) 6261 4212 to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening This collection is open for listening. Restrictions on use Copies of this collection may be made for private research. Permission must be sought from the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1966-1967 Extent: 55 sound tapes : analogue, mono. Production history These recordings were collected between November 1965 and October 1967 by linguist Margaret Sharpe, an AIAS (now AIATSIS) grantee, while on fieldwork at Woodenbong in New South Wales, Woorabinda, Emerald and Brisbane in Queensland, and Ngukurr, Nutwood and Minyerri in the Northern Territory. The purpose of the field trips was to document the languages, stories and songs of the Indigenous peoples of these areas. The cultures which were investigated are Yugambeh and Bundjalung of northern NSW; Gangulu, Gooreng Gooreng, Mamu (Malanda dialect), Guugu Yimidhirr, Wakaya, Wangkumara, Kuungkari, Biri and Galali from Queensland; and Alawa, Mara, Ritharrngu, Warndarrang, Ngalakan, Yanyuwa, Mangarrayi and Gurdanji from the Northern Territory. The interviewees and performers include Joe Culham, Adrian [Eddie] Conway, Johnson Mate Mate, Willie Toolban, Henry Bloomfield, Victor Reid, Willie Healy, Fred Grogan, Nugget Swan, Ted Maranoa, Willie Rookwood, Rosie Williams, Barnabas Roberts, Bill Turnbull, Dan Cot, Bessie Farrell, Isaac Joshua, Norman, Ivy, Matthew, Caleb Roberts, Limmen Harry, Kellie, Kittie, Clancy Roberts, Francis, Viola Tiers and unidentified contributors. -

Flood Watch Areas Arnhem Coastal Rivers Northern Territory River Basin No

Flood Watch Areas Arnhem Coastal Rivers Northern Territory River Basin No. Blyth River 15 Buckingham River 17 East Alligator River 12 Goomadeer River 13 A r a f u r a S e a Goyder River 16 North West Coastal Rivers Liverpool River 14 T i m o r S e a River Basin No. Adelaide River 4 below Adelaide River Town Arnhem Croker Coastal Daly River above Douglas River 10 Melville Island Rivers Finniss River 2 Island Marchinbar Katherine River 11 Milikapiti ! Island Lower Daly River 9 1 Elcho ! Carpentaria Coastal Rivers Mary River 5 1 Island Bathurst Nguiu Maningrida Galiwinku River Basin No. Island 12 ! ! Moyle River 8 ! Nhulunbuy 13 Milingimbi ! Yirrkala ! Calvert River 31 South Alligator River 7 DARWIN ! ! Howard " Oenpelli Ramingining Groote Eylandt 23 Tiwi Islands 1 2 Island 17 North West 6 ! 14 Koolatong River 21 Jabiru Upper Adelaide River 3 Coastal 15 Batchelor 4 Limmen Bight River 27 Wildman River 6 Rivers ! 16 7 21 McArthur River 29 3 5 ! Bickerton Robinson River 30 Island Daly River ! Groote Roper River 25 ! ! Bonaparte Coastal Rivers Bonaparte 22 Alyangula Eylandt Rosie River 28 Pine 11 ! 9 Creek Angurugu River Basin No. Coastal 8 Towns River 26 ! ! Kalumburu Rivers Numbulwar Fitzmaurice River 18 ! Walker River 22 Katherine 25 Upper Victoria River 20 24 Ngukurr 23 Waterhouse River 24 18 ! Victoria River below Kalkarindji 19 10 Carpentaria G u l f 26 Coastal Rivers ! o f ! Wyndham Vanderlin C a r p e n t a r i a ! 28 Kununurra West Island Island 27 ! Borroloola 41 Mount 19 Barnett Mornington ! ! Dunmarra Island Warmun 30 (Turkey 32 Creek) ! 29 Bentinck 39 Island Kalkarindji 31 ! Elliott ! ! Karumba ! 20 ! Normanton Doomadgee Burketown Fitzroy ! Crossing Renner ! Halls Creek ! Springs ! ! Lajamanu 41 Larrawa ! Warrego Barkly ! 40 33 Homestead QLD ! Roadhouse Tennant ! Balgo Creek WA ! Hill Camooweal ! 34 Mount Isa Cloncurry ! ! ! Flood Watch Area No. -

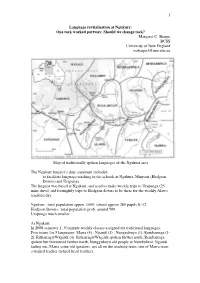

1 Language Revitalisation at Ngukurr: One Tack Worked Partway

1 Language revitalisation at Ngukurr: One tack worked partway: Should we change tack? Margaret C. Sharpe BCSS University of New England [email protected] Map of traditionally spoken languages of the Ngukurr area The Ngukurr linguist’s duty statement included: to facilitate language teaching in the schools at Ngukurr, Minyerri (Hodgson Downs) and Urapunga The linguist was based at Ngukurr, and used to make weekly trips to Urapunga (25 mins drive) and fortnightly trips to Hodgson downs to be there for the weekly Alawa teaching day. Ngukurr: total population appox. 1500; school approx 280 pupils K-12. Hodgson Downs: total population prob. around 500. Urapunga much smaller. At Ngukurr: In 2008 semester 1, 30 minute weekly classes assigned for traditional languages. Five teams for 5 languages: Marra (4) , Ngandi (1) , Nunggubuyu (1), Rembarrnga (1- 2), Ritharrngu/Wägilak (4). Ritharrngu/Wägilak spoken further north, Rembarrnga spoken but threatened further north, Nunggubuyu old people at Numbulwar, Ngandi fading out, Marra some old speakers, not all on the teaching team, one of Marra team a trained teacher (retired head teacher). 2 School language teaching for some years has been words in a chosen domain, and some songs: e.g. in Marra: Nga-jurra na-balba-yurr , na-balba-yurr, na-balba-yurr Nga-jurra na-balba-yurr, Jurr-nga-ju na-warlanyan-i I-went masc-river-to catch-I-did masc-fish-for Minyerri School: a trained local teacher in charge, not an Alawa speaker, 1-2 Alawa speakers, two non-speaking Alawa helpers. 30 minute lessons, but better organised than at Ngukurr because co-ordinated by a trained teacher. -

Flood Risk Management in Australia Building Flood Resilience in a Changing Climate

Flood Risk Management in Australia Building flood resilience in a changing climate December 2020 Flood Risk Management in Australia Building flood resilience in a changing climate Neil Dufty, Molino Stewart Pty Ltd Andrew Dyer, IAG Maryam Golnaraghi (lead investigator of the flood risk management report series and coordinating author), The Geneva Association Flood Risk Management in Australia 1 The Geneva Association The Geneva Association was created in 1973 and is the only global association of insurance companies; our members are insurance and reinsurance Chief Executive Officers (CEOs). Based on rigorous research conducted in collaboration with our members, academic institutions and multilateral organisations, our mission is to identify and investigate key trends that are likely to shape or impact the insurance industry in the future, highlighting what is at stake for the industry; develop recommendations for the industry and for policymakers; provide a platform to our members, policymakers, academics, multilateral and non-governmental organisations to discuss these trends and recommendations; reach out to global opinion leaders and influential organisations to highlight the positive contributions of insurance to better understanding risks and to building resilient and prosperous economies and societies, and thus a more sustainable world. The Geneva Association—International Association for the Study of Insurance Economics Talstrasse 70, CH-8001 Zurich Email: [email protected] | Tel: +41 44 200 49 00 | Fax: +41 44 200 49 99 Photo credits: Cover page—Markus Gebauer / Shutterstock.com December 2020 Flood Risk Management in Australia © The Geneva Association Published by The Geneva Association—International Association for the Study of Insurance Economics, Zurich. 2 www.genevaassociation.org Contents 1. -

Gulf Water Study Roper River Region

Gulf Water Study Roper River Region Front cover: Painting of the Rainbow Serpent by Rex Wilfred. (see Appendix A for the story of the painting) Satellite image of the Roper River. Yawurrwarda Lagoon. GULF WATER STUDY Early morning at Roper Bar, Roper River WATER RESOURCES OF THE ROPER RIVER REGION REPORT 16/2009D U. ZAAR DARWIN NT © Northern Territory of Australia, 2009 ISBN 978-1-921519-64-2 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was co -funded through the Australian Government Water Smart Australia Program and the Northern Territory Government Department of Natural Resources, Environment the Arts and Sport. I would like to thank my colleagues who provided help on this project: Peter Jolly (now retired) who instigated this project; Des Yin Foo for his generous support as our team manager; Anthony Knapton, my co-worker on this project who provided technical and field assistance; Steve Tickell, Danuta Karp and Jon Sumner for their technical advice; Lynton Fritz for his outstanding cartographic skills in drawing up the maps; Renee Ramsay for the production of the GIS and collation of the DVD and our experienced technical team – Rodney Metcalfe, Steve Hester, Roger Farrow and Rob Chaffer for all their efficient fieldwork. A special thanks also to Phil O’Brien who not only provided enthusiastic field assistance but wise advice. I take pleasure in also thanking members of our technical working group; Max Gorringe - the manager of Elsey Station, Frank Shadforth – the manager of Seven Emu Station and Glenn Wightman – ethnobiologist who all kindly took the time to provide advice at our meetings. All were always ready to help.