The Morion: an Introduction to Its Development, Form, & Function

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

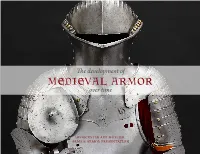

MEDIEVAL ARMOR Over Time

The development of MEDIEVAL ARMOR over time WORCESTER ART MUSEUM ARMS & ARMOR PRESENTATION SLIDE 2 The Arms & Armor Collection Mr. Higgins, 1914.146 In 2014, the Worcester Art Museum acquired the John Woodman Higgins Collection of Arms and Armor, the second largest collection of its kind in the United States. John Woodman Higgins was a Worcester-born industrialist who owned Worcester Pressed Steel. He purchased objects for the collection between the 1920s and 1950s. WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 3 Introduction to Armor 1994.300 This German engraving on paper from the 1500s shows the classic image of a knight fully dressed in a suit of armor. Literature from the Middle Ages (or “Medieval,” i.e., the 5th through 15th centuries) was full of stories featuring knights—like those of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, or the popular tale of Saint George who slayed a dragon to rescue a princess. WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 4 Introduction to Armor However, knights of the early Middle Ages did not wear full suits of armor. Those suits, along with romantic ideas and images of knights, developed over time. The image on the left, painted in the mid 1300s, shows Saint George the dragon slayer wearing only some pieces of armor. The carving on the right, created around 1485, shows Saint George wearing a full suit of armor. 1927.19.4 2014.1 WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 5 Mail Armor 2014.842.2 The first type of armor worn to protect soldiers was mail armor, commonly known as chainmail. -

EVA Checklist

JSC-48023 EVA Checklist Mission Operations Directorate EVA, Robotics, and Crew Systems Operations Division Generic, Rev H March 4, 2005 NOTE For STS-114 and subsequent (chronological) flights per current schedule. National Aeronautics and Space Administration Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas Verify this is the correct version for the pending operation (training, simulation or flight). Electronic copies of FDF books are available. URL: http://mod.jsc.nasa.gov/do3/FDF/index.html Incorporates the following: 482#: EVA-1529 EVA-1555 EVA-1564 MULTI-1693 EVA-1530 EVA-1556 EVA-1565 MULTI-1694 EVA-1543 EVA-1557 EVA-1566 EVA-1544A EVA-1558 EVA-1567 EVA-1546 EVA-1559 EVA-1568 EVA-1551 EVA-1560 EVA-1569 EVA-1552 EVA-1561 EVA-1570(P) EVA-1553 EVA-1562 EVA-1554 EVA-1563 (P) – Partially implemented in this publication AREAS OF TECHNICAL RESPONSIBILITY Book Manager DX35/P. Boehm 281-483-5447 Task Procedures DX32/K. Shook 281-483-4474 ii EVA/ALL/GEN H EVA CHECKLIST LIST OF EFFECTIVE PAGES GENERIC 12/07/87 PCN-6 11/10/06 PCN-13 02/15/08 REV H 03/04/05 PCN-7 02/20/07 PCN-14 04/15/08 PCN-1 04/08/05 PCN-8 05/22/07 PCN-15 08/28/08 PCN-2 06/10/05 PCN-9 06/15/07 PCN-16 01/16/09 PCN-3 08/01/05 PCN-10 07/18/07 PCN-17 04/07/09 PCN-4 06/12/06 PCN-11 09/28/07 PCN-5 08/17/06 PCN-12 12/14/07 Sign Off ...................... -

Unclassified Fourteenth- Century Purbeck Marble Incised Slabs

Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London, No. 60 EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS This book is published with the generous assistance of The Francis Coales Charitable Trust. EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS Sally Badham and Malcolm Norris The Society of Antiquaries of London First published 1999 Dedication by In memory of Frank Allen Greenhill MA, FSA, The Society of Antiquaries of London FSA (Scot) (1896 to 1983) Burlington House Piccadilly In carrying out our study of the incised slabs and London WlV OHS related brasses from the thirteenth- and fourteenth- century London marblers' workshops, we have © The Society of Antiquaries of London 1999 drawn very heavily on Greenhill's records. His rubbings of incised slabs, mostly made in the 1920s All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, and 1930s, often show them better preserved than no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval they are now and his unpublished notes provide system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, much invaluable background information. Without transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, access to his material, our study would have been less without the prior permission of the copyright owner. complete. For this reason, we wish to dedicate this volume to Greenhill's memory. ISBN 0 854312722 ISSN 0953-7163 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the -

Spring Flyer 2021

SPRING FLYER 2021 Be Smart. Be Safe. Be Sure.TM ® Third Party MAXVIEW Face Shields Certification • Extra-large stylish crown and wraparound face shield frame • High-impact polycarbonate window (with or without anti-fog) • 370 Speed Dial™ premium ratcheting headgear suspension • All models meet or exceed ANSI Z87.1+ high impact standards The 370 Speed Dial™ • CSA certified to CAN/CSA Z94.3 standards is highlighted by • CE certified Jackson’s famous “Easy Grab-Easy Turn” oversized adjusting dial PROD. NO. Suspension Window Tint Coating List Sale and patented swivel adjuster band— 14200 Ratcheting Clear None $41.95 $34.95 an industry best! 14201 Ratcheting Clear Anti-fog $59.95 $49.95 14200 QUAD 500® Faceshields • Stylish crown and wraparound face shield frame • All models meet or exceed ANSI Z87.1+ • Premium molded polycarbonate AF window high impact standards • 370 Speed Dial™ premium ratcheting • Certified to CAN/CSA Z94.3 standards 14230/14233 headgear suspension on 14220, 14230, 14233 • CE certified 14220 PROD. NO. Description Suspension List Sale 14220 Clear Antifog PC Ratcheting $69.95 $58.50 14225 Clear HHIS Systems Universal Adaptor $68.85 $57.50 14225 14230 Clear Antifog PC-Shade 5 FLIP Ratcheting $89.95 $75.25 Third Party Certification Clear Antifog PC-Shade 8 FLIP Ratcheting $92.95 14233 $77.75 14235 14235 Clear Antifog PC-Shade 5 FLIP w/HHIS Universal Adaptor $88.95 $74.25 MAXVIEW® Replacement Visors QUAD 500® Replacement Visors • Extra-large polycarbonate • For added protection, the molded 14250 window for superior optics and window can be completely framed industry-leading panoramic on the sides and chin and features views and anti-fog coating an extra-large crown • The Quad 500® offers exceptional panoramic views with virtually no distortion 14255 14214 PROD. -

Cr3v05 Maquetación 1

CAMINO REAL 2:3 (2010): 11-33 Celluloid Conquistadors: Images of the Conquest of Mexico in Captain from Castile (1947) STEPHEN A. COLSTON ABSTRACT The Spanish Conquest of Aztec Mexico (1519-21) forever transformed greater North America, Europe, and regions beyond. In spite of this significance, there is only one extant motion picture that has attempted to portray features of this epic event. Re- leased in 1947 by Twentieth Century-Fox, Captain from Castile was based on a novel of the same title and offers images of the Conquest that are intertwined with fact and fic- tion. Drawing upon the novel and elements of the Conquest story itself, this study se- parates and examines the threads of fact and fantasy that form the fundamental fabric of this film’s recounting of the Spanish Conquest. This analysis is enhanced by infor- mation found in unpublished documents from several collections of motion picture pro- duction materials. Ultimately, the images of the Spanish Conquest that emerge in Captain from Castile reveal some elements of genuine historicity but they more often reflect, in typical Hollywood fashion, the aspirations of a studio more concerned with achieving box office success than historical accuracy. Keywords: film, Hollywood, Conquest, Mexico, Cortés, Aztecs. Stephen A. Colston is an Associate Professor of History at San Diego State University. Colston, S. “Celluloid Conquistadors: Images of the Conquest of Mexico in Captain from Castile (1947).” Camino Real. Estudios de las Hispanidades Norteamericanas. Alcalá de Henares: Instituto Franklin - UAH, 2:3 (2010): 11- 33. Print. Recibido: 27/10/2010; 2ª versión: 26/11/2010 11 CAMINO REAL RESUMEN La conquista española del México azteca (1519 - 1521) transformó para siempre América del Norte, Europa y más allá. -

2008 Things to Do

2013: Low or No Cost Things to Do With Children under 9 You can attend the following activities on a drop-in basis unless stated otherwise: Please note that there is a list at the end of this document showing the passes available at area libraries which are referenced under the “cost” column. In addition to the chronological listings here, there are daily or every- weekend bargains at the end of the August listings. Date Activity Details _______________________________Cost July 1 Magician Mike Bent at the J.V. Fletcher Library in Westford, 7:00 pm, for Ages 5 & Up $2 Tickets available at the Children’s Desk or by phone: 978-692-5555. 50 Main Street. July 1 “Oz the Great & Powerful” at Gleason Library, Carlisle, 4:00, For Grades 1-8, Rated PG Free July 1 Storytime for Walkers Age 12-30 Months at Chelmsford Library, 25 Boston Rd., 10-10:30 Free Mostly rhymes and songs – this is an in-between group for children who are walking independently but not quite ready to sit for a traditional storytime. www.chelmsfordlibrary.org July 1 Special Themed Storytime for Toddlers at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 10:30-11:15 $10 Includes storytime, looking activities in the galleries, and art project. Geared to ages 4 and Adult under with an adult. Visitors meet at Sharf Visitor Center. www.mfa.org. Ages 6 & under free. w/ lib. pass July 2 Art & Stories for 4’s & 5’s, 10:30, at Harvard Public Library, 4 Pond Rd., 978-456-2381 Free Longer picture book stories combined with a process art project to enable children to explore art materials in an open-ended creative manner. -

What's the Use of Wondering If He's Good Or Bad?: Carousel and The

What’s the Use of Wondering if He’s Good or Bad?: Carousel and the Presentation of Domestic Violence in Musicals. Patricia ÁLVAREZ CALDAS Universidad de Santiago de Compostela [email protected] Recibido: 15.09.2012 Aceptado: 30.09.2012 ABSTRACT The analysis of the 1956 film Carousel (Dir. Henry King), which was based on the 1945 play by Rodgers and Hammerstein, provides a suitable example of a musical with explicit allusions to male physical aggression over two women: the wife and the daughter. The issue of domestic violence appears, thus, in a film genre in which serious topics such as these are rarely present. The film provide an opportunity to study how the expectations and the conventions brought up by this genre are capable of shaping and transforming the presentation of Domestic Violence. Because the audience had to sympathise with the protagonists, the plot was arranged to fulfil the conventional pattern of a romantic story inducing audiences forget about the dark themes that are being portrayed on screen. Key words: Domestic violence, film, musical, cultural studies. ¿De qué sirve preocuparse por si es bueno o malo?: Carrusel y la presentación de la violencia doméstica en los musicales. RESUMEN La película Carrusel (dirigida por Henry King en 1956 y basada en la obra de Rodgers y Hammerstein de 1945), nos ofrece un gran ejemplo de un musical que realiza alusiones explícitas a las agresiones que ejerce el protagonista masculino sobre su esposa y su hija. El tema de la violencia doméstica aparece así en un género fílmico en el que este tipo de tratamientos rara vez están presentes. -

Acta Periodica Duellatorum, Conference Proceedings 7

Acta Periodica Duellatorum, Conference Proceedings 7 DOI 10.1515/apd-2017-0006 The armour of the common soldier in the late middle ages. Harnischrödel as sources for the history of urban martial culture Regula Schmid, University of Berne, [email protected] Abstract – The designation Harnischrödel (rolls of armour) lumps together different kinds of urban inventories. They list the names of citizens and inhabitants together with the armour they owned, were compelled to acquire within their civic obligations, or were obliged to lend to able-bodied men. This contribution systematically introduces Harnischrödel of the 14th and 15th c. as important sources for the history of urban martial culture. On the basis of lists preserved in the archives of Swiss towns, it concentrates on information pertaining to the type and quality of an average urban soldier’s gear. Although the results of this analysis are only preliminary – at this point, it is not possible to produce methodologically sound statistics –, the value of the lists as sources is readily evident, as only a smattering of the once massive quantity of actual objects has survived down to the present time. Keywords – armour, common soldier, source, methodology, urban martial culture, town, middle ages. I. INTRODUCTION The designation Harnischrödel (“rolls1 of armour”) lumps together different kinds of urban inventories. They list the names of citizens and inhabitants together with the armour they owned, were compelled to acquire within their civic obligations, or were obliged to lend to able-bodied men. Harnischrödel resulted from the need to assess the military resources of the town and its territory available in times of acute military danger. -

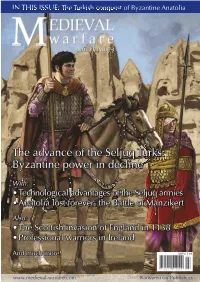

The Advance of the Seljuq Turks: Byzantine Power in Decline

IN THIS ISSUE: The Turkish conquest of Byzantine Anatolia VOL lll, ISSUE 3 The advance of the Seljuq Turks: Byzantine power in decline With: • Technological advantages of the Seljuq armies • Anatolia lost forever: the Battle of Manzikert Also: • The Scottish invasion of England in 1138 • Professional warriors in Ireland And much more! GBP £ 5.99 www.medieval-warfare.com Karwansaray Publishers Medieval Warfare III-3.indd 1 07-05-13 14:02 Medieval Warfare III-3.indd 2 07-05-13 14:02 CONTENTS 4 NEWS AND LETTERS 28 The Battle of Manzikert Publisher: Rolof van Hövell tot Westerflier When Anatolia was lost forever Editor in chief: Jasper Oorthuys Editorial staff: Dirk van Gorp (editor Medieval Warfare), Duncan B. Campbell (copy-editor) THEME Marketing & media manager: Christianne C. Beall The advance of the Seljuq Turks: Byzantine power in decline Contributors: Raffaele D’Amato, Stephen Bennett, Arnold Blumberg, Kenneth Cline, Sidney Dean, Ronald A gathering storm Delval, Joshua Gilbert, James Gilmer, Peter Konieczny, 6 Sean McGlynn, Konstantin Nossov, Murat Özveri, Łukasz Historical introduction Różycki, Patryk Skupniewicz, William Stroock, Nils Visser. 35 The Komnenian response Illustrators: Giorgio Albertini, Carlos Garcia, Vladimir to seljuq victories Golubev, Marc Grunert, Milek Jakubiec, Jason Juta, Julia The development of the Lillo, Jose Antonio Gutierrez Lopez, ªRU-MOR, Graham Byzantine army Sumner. Special thanks goes to Raffaele D’Amato for providing additional pictures. The art of Byzantine Design & layout: MeSa Design (www.mesadesign.nl) -

Schofield Barracks

ARMY ✭✭ AIR FORCE ✭✭ NAVY ✭✭ MARINES ONLINE PORTAL Want an overview of everything military life has to offer in Hawaii? This site consolidates all your benefits and priveleges and serves all branches of the military. ON BASE OFF BASE DISCOUNTS • Events Calendar • Attractions • Coupons & Special Offers • Beaches • Recreation • Contests & Giveaways • Attractions • Lodging WANT MORE? • Commissaries • Adult & Youth Go online to Hawaii • Exchanges Education Military Guide’s • Golf • Trustworthy digital edition. • Lodging Businesses Full of tips on arrival, • Recreation base maps, phone • MWR numbers, and websites. HawaiiMilitaryGuide.com 4 Map of Oahu . 10 Honolulu International Airport . 14 Arrival . 22 Military Websites . 46 Pets in Paradise . 50 Transportation . 56 Youth Education . 64 Adult Education . 92 Health Care . 106 Recreation & Activities . 122 Beauty & Spa . 134 Weddings. 138 Dining . 140 Waikiki . 148 Downtown & Chinatown . 154 Ala Moana & Kakaako . 158 Aiea/West Honolulu . 162 Pearl City & Waipahu . 166 Kapolei & Ko Olina Resort . 176 Mililani & Wahiawa . 182 North Shore . 186 Windward – Kaneohe . 202 Windward – Kailua Town . 206 Neighbor Islands . 214 6 PMFR Barking Sands,Kauai . 214 Aliamanu Military Reservation . 218 Bellows Air Force Station . 220 Coast Guard Base Honolulu . 222 Fort DeRussy/Hale Koa . 224 Fort Shafter . 226 Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam . 234 MCBH Camp Smith . 254 MCBH Kaneohe Bay . 258 NCTAMS PAC (JBPHH Wahiawa Annex) . 266 Schofield Barracks . 268 Tripler Army Medical Center . 278 Wheeler Army Airfield . 282 COVID-19 DISCLAIMER Some information in the Guide may be compromised due to changing circumstances. It is advisable to confirm any details by checking websites or calling Military Information at 449-7110. HAWAII MILITARY GUIDE Publisher ............................Charles H. -

Armour As a Symbolic Form

Originalveröffentlichung in: Waffen-und Kostümkunde 26 (1984), Nr. 2, S. 77-96 Armour As a Symbolic Form By Zdzislaw Zygulski Jr. „It is perfectly possible to argue that some distinctive objects are made by the mind, and that these objects, while appearing to exist objectively, have only a fictional reality." E. W. Said, Orientalism, New York 1979 Somewhere in the remote past of mankind armour was born, its basic purpose being to protect the soft and vulnerable human body in combat. It is somewhat surprising that in the course of Darwinian evolution man lost his natural protective attributes, above all hair, and slowly became what is called, with some malice, ,,the naked ape". Very soon man the hunter adopted animal skins as his first dress and also as armour. The tradition of an armour of leather is very ancient and still lingers in the word ,,cuirass". Various natural substances such as hard wood, plant fibres, bones, hoofs, or even tusks were used to make the body protection more resistant, but as soon as metallurgy had been mastered metal became the supreme material for all kinds of weaponry, both offensive and defensive. Since a blow to the head was often lethal, special attention was paid to the pro tection of that principal part of the body: early bronze helmets of conical shape are represented in the Sume rian art as early as the third millennium B. C.l. The shield, a prehistoric invention, although detached from the body and movable, may also be considered as a kind of armour. In the course of centuries a great number of types of armour and innumerable actual specimens were crea ted. -

Knights at the Museum Interactive Qualifying Project Submitted to the Faculty of the Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation

Knights! At the Museum Knights at the Museum Interactive Qualifying Project Submitted to the faculty of the Worcester Polytechnic Institute in fulfillment of the requirements for graduation. By: Jonathan Blythe, Thomas Cieslewski, Derek Johnson, Erich Weltsek Faculty Advisor: Jeffrey Forgeng JLS IQP 0073 March 6, 2015 1 Knights! At the Museum Contents Knights at the Museum .............................................................................................................................. 1 Authorship: .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Abstract: ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Introduction to Metallurgy ...................................................................................................................... 12 “Bloomeries” ......................................................................................................................................... 13 The Blast Furnace ................................................................................................................................. 14 Techniques: Pattern-welding, Piling, and Quenching ......................................................................