Remnants of Some Late Sixteenth-Century Trumpet Ensemble Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Lute Manuscripts and Scribes 1530-1630

ENGLISH LUTE MANUSCRIPTS AND SCRIBES 1530-1630 An examination of the place of the lute in 16th- and 17th-century English Society through a study of the English Lute Manuscripts of the so-called 'Golden Age', including a comprehensive catalogue of the sources. JULIA CRAIG-MCFEELY Oxford, 2000 A major part of this book was originally submitted to the University of Oxford in 1993 as a Doctoral thesis ENGLISH LUTE MANUSCRIPTS AND SCRIBES 1530-1630 All text reproduced under this title is © 2000 JULIA CRAIG-McFEELY The following chapters are available as downloadable pdf files. Click in the link boxes to access the files. README......................................................................................................................i EDITORIAL POLICY.......................................................................................................iii ABBREVIATIONS: ........................................................................................................iv General...................................................................................iv Library sigla.............................................................................v Manuscripts ............................................................................vi Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century printed sources............................ix GLOSSARY OF TERMS: ................................................................................................XII Palaeographical: letters..............................................................xii -

Johann Helmich Roman GOLOVINMUSIKEN Höör Barock & Dan Laurin

Unknown artist: Utsikt från Slottsbacken, vinterbild (‘View from the Castle Slope, Stockholm’). Oil on canvas, 81.5 x 146.5 cm, beginning of the 18th century. The painting must have been made shortly after 1697 when the old Royal Palace was destroyed in a fire – the artist has included the ruins (below). Across the water is the so-called Bååtska Palatset, where the Golovin Music was performed for the first time in 1728. Johann Helmich Roman GOLOVINMUSIKEN Höör Barock & Dan Laurin BIS-2355 Johan Helmich Roman (1694–1758) Golovinmusiken – The Golovin Music Musique satt til en Festin hos Ryska Ministren Gref Gollowin (Music for a banquet held by the Russian envoy Count Golovin) Höör Barock Dan Laurin recorders and direction Performing version by Dan Laurin, based on the composer’s autograph and the score by Ingmar Bengtsson and Lars Frydén published by Edition Reimers. In Roman’s autograph manuscript each movement has a number, but there are no other headings in the form of titles or tempo markings. Those provided here, in square brack- ets, are the performers’ suggestions for how the different pieces may be interpreted in terms of genre or character. first complete recording TT: 81'53 2 1 [Allegro] Violin 1, violin 2, viola, cello, double bass, mandora, harpsichord 2'09 2 [Ouverture] Sixth flute**, oboe, oboe d’amore, bassoon, violin 1, violin 2, 1'51 viola, cello, double bass, mandora, harpsichord 3 [Larghetto] Tenor recorder, voice flute***, bass recorder**, violin 2, 3'06 viola, cello, double bass, mandora 4 [Allegro assai] Violin 1, violin -

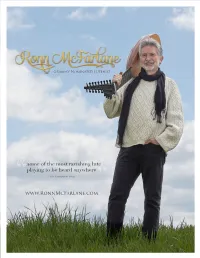

…Some of the Most Ravishing Lute Playing to Be Heard Anywhere

Grammy-Nominated Lutenist …some of the most ravishing lute playing to be heard anywhere “ ~The Washington Times ” www.RonnMcFarlane.com probably the fnest living exponent of his instrument AbeguilingrecordingbytheUSlutenistwhich ~The Times Colonist, Victoria, B.C. beautifully balances traditional Scottish and Irish tunes with works by Turlough O’Carolan “ ~BBC Music Magazine “ ” GRAMMY-nominated lutenist, Ronn McFarlane brings the lute - the most popular instrument of the ” Renaissance - into today’s musical mainstream making it accessible to a wider audience. Since taking up the lute in 1978, Ronn has made his mark in music as the founder of Ayreheart, a founding member of the Baltimore Consort, touring 49 of the 50 United States, Canada, England, Scotland, Netherlands, Germany and Austria, and as a guest artist with Apollo’s Fire, The Bach Sinfonia, The Catacoustic Consort, The Folger Consort, Houston Grand Opera, The Oregon Symphony, The Portland Baroque Orchestra, and The Indianapolis Baroque Orchestra. Born in West Virginia, Ronn grew up in Maryland. At thirteen, upon hearing “Wipeout” by the Surfaris, he fell madly in love with music and The Celtic Lute taught himself to play on a “cranky sixteen-dollar steel string guitar.” Released in 2018, Ronn's newest solo Ronn kept at it, playing blues and rock music on the electric guitar while album features all-new arrangements of traditional Irish and Scottish folk music studying classical guitar. He graduated with honors from Shenandoah Conservatory and continued guitar studies at Peabody Conservatory before turning his full attention and energy to the lute in 1978. McFarlane was a faculty member of the Peabody Conservatory from Solo Discography 1984 to 1995, teaching lute and lute-related subjects. -

Recorder Music Marcello · Vivaldi · Bellinzani

Recorder Music Marcello · Vivaldi · Bellinzani Manuel Staropoli recorder · Gioele Gusberti cello · Paolo Monetti double bass Pietro Prosser archlute, Baroque guitar · Manuel Tomadin harpsichord, organ Recorder Music Benedetto Marcello 1686–1739 Antonio Vivaldi 1678–1741 Paolo Benedetto Bellinzani Sonata No.12 in F Concerto in D minor Sonata No.12 in D minor for flute and b.c. arranged for flute and cembalo obligato for flute and b.c. 1. Adagio 3’03 14. Allegro 3’25 25. Largo 2’02 2. Minuet. Allegro 0’51 15. Largo 3’25 26. (Allegro) 1’59 3. Gavotta. Allegro 0’54 16. Allegro 3’32 27. Cembalo only for breath 4. Largo 1’04 of the Flute 1’16 5. Ciaccona. Allegro 3’51 Paolo Benedetto Bellinzani 28. Follia 8’14 Sonata No.10 in F Paolo Benedetto Bellinzani for flute and b.c. c.1690–1757 17. Adaggio 3’58 Sonata No.7 in G minor 18. Presto 2’12 for flute and b.c. 19. Adaggio 1’08 Manuel Staropoli recorder 6. Largo 1’52 20. (Gavotta) 1’57 Gioele Gusberti cello 7. Presto 1’50 Paolo Monetti double bass 8. Largo 1’43 Benedetto Marcello Pietro Prosser archlute, Baroque guitar 9. Giga (without tempo indication) 1’37 Sonata No.8 in D minor Manuel Tomadin harpsichord, organ for flute and b.c. Benedetto Marcello 21. Adagio 3’09 Sonata No.6 in G 22. Allegro 2’30 for flute and b.c. 23. Largo 1’32 10. Adagio 3’35 24. Allegro 3’59 11. Allegro 3’13 12. Adagio 1’28 13. -

FOMRHI Quarterly

I No. 14 JANUARY 1979 FOMRHI Quarterly BULLETIN 14 AND SUPPLEMENT 2 LIST OF MEMBERS 3rd SUPPLEMENT 14 FoMRHI BOOK NEWS 18 COMMUNICATIONS 171 Review: Will Jansen, The Bassoon, part I. Jeremy Montagu. 19 172 Review: "Divisions", Journal. Jeremy Montagu. 21 173 A Possible Soundboard Finish For Lutes And Guitars. Ian Harwood. 22 174 On The Time Of lnventlon Of Overspun Strings. D.A. & E.S. 24 175 The Identity Of 18th Century 6 Course 'Lutes'. Martyn Hodgson. 25 176 Early 16th Century Lute Reconstructlons. Martyn Hodgson. 28 177 A Table To Convert Plaln Gut (Or Nylon) String Sizes To Equivalent Overwound String Specifications. Martyn Hodgson. 29 178 "Mensur" ? Ugh ! Eph Segerman. 31 179 Fret Distances From The Nut For Every Interval Above The Open String. Djilda Abbott, Eph Segerman and Pete Spencer. 32 180 Making Reamers On A Shoestring. Bob Marvin. 37 181 Blown Resonance Of Baroque Transverse Flute, II Characteristic Frequency. Felix Raudonikas. 39 182 Planning A Workshop. John Rawson. 42 183 On Mersenne's Twisted Data And Metal Strings. Cary Karp. 44 184 Notes On European Harps. Tim Hobrough. 47 185 Peg Taper Finisher / Cutter. Geoff Mather. 57 186 The Viola Pomposa. Mark Mervyn Smith. 59 187 More On The Sizes Of English (And Other) Viols. E.S. & D.A. 63 < Fellowship of Makers and Restorers of Historical Instruments 7 Pickwick Road, Dulwich Village, London SE21 7JN , U.K. FELLOWSHIP of MAKERS and RESTORERS of HISTORICAL INSTRUMENTS Bulletin no.14 January, 1979 A happy new year to rather less than half of our members - to those of you who have remembered to renew your subscriptions so far. -

Records Ofearfv~ English Drama

:I'M! - 1982 :1 r P" A newsletter published by University of Toronto Press in association with Erindale College, University of Toronto and Manchester University Press . JoAnna Dutka, editor Records ofEarfv~ English Drama The biennial bibliography of books and articles on records of drama and minstrelsy contributed by Ian Lancashire (Erindale College, University of Toronto) begins this issue ; John Coldewey (University of Washington) discusses records of waits in Nottinghamshire and what the activities of the waits there suggest to historians of drama ; David Mills (University of Liverpool) presents new information on the iden- tity of Edward Gregory, believed to be the scribe of the Huntington manuscript of the Chester cycle. IAN LANCASHIRE Annotated bibliography of printed records of early British drama and minstrelsy for 1980-81 This list, covering publications up to 1982 that concern documentary or material records of performers and performance, is based on a wide search of recent books, periodicals, and record series publishing evidence of pre-18th-century British history, literature, and archaeology . Some remarkable achievements have appeared in these years. Let me mention seven, in the areas of material remains, civic and town records, household papers, and biography . Brian Hope-Taylor's long-awaited report on the excavations at Yeavering, Northumberland, establishes the existence of a 7th-century theatre modelled on Roman structures . R.W. Ingram has turned out an edition of the Coventry records for REED that discovers rich evidence from both original and antiquarian papers, more than we dared hope from a city so damaged by fire and war. The Malone Society edition of the Norfolk and Suffolk records by David Galloway and John Wasson is an achievement of a different sort : the collection of evidence from 41 towns has presented them unusual editorial problems, in the solv- ing of which both editors and General Editor Richard Proudfoot have earned our gratitude . -

The Early Mandolin: the Mandolino and the Neapolitan Mandoline

Performance Practice Review Volume 4 Article 6 Number 2 Fall "The aE rly Mandolin: The aM ndolino and the Neapolitan Mandoline." By James Tyler and Paul Sparks Donald Gill Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Gill, Donald (1991) ""The Early Mandolin: The aM ndolino and the Neapolitan Mandoline." By James Tyler and Paul Sparks," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 4: No. 2, Article 6. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199104.02.06 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol4/iss2/6 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 202 Reviews of Books James Tyler and Paul Sparks. The Early Mandolin: the Mandolino and the Neapolitan mandoline. Early Music Series, 9. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989. x. 186p. When I acquired a 1734 mandolino in the nineteen-thirties, having somehow raised fifteen shillings (about $1.85) for it, I was thrilled to have my first historical instrument, but had no idea that such a tiny, frail thing could have been used for real music making. Nor did I suspect that I would eventually develop such an interst in, and enjoyment of, the whole family of "little lutes," of which the mandolino is such a prominent member. Consideration of these instruments is bedevilled by names, as is so often the case: mandore, mandora, mandola, bandurria, bandola, pandurina, Milanese mandolin, mandolino, mandoline, even soprano lute — how can some semblance of order and reason be brought to the subject. -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

For Mandora the Harmony of Contrasts

95869 forMusic Mandora Gábor Tokodi mandora Music for Mandora The Harmony of Contrasts Viva fui in sylvis Alive I was in the woods, Giuseppe Antonio Brescianello Anonym, Budapest tandem percussa securi Finally, though, the axe struck me. (1690-1757) Suite in C Viva nihil dixi Alive I spoke nothing, Sonata in G minor Egyetemi könyvtár, Ms. F 36 mortua dulce cano Dead I now sing sweetly. 1. I. Allegro 2’18 12. I. Capricio 1’41 2. II. Menuet – Trio 4’47 13. II. Alamand 1’57 This Latin distich, describing the transformation of a tree into a resonating body, was 3. III. Bourée 2’05 14. III. Allegro 1’41 commonplace from the 16th until the 18th century. Usually it was associated with the 4. IV. Menuet 1’19 15. IV. Aria 2’30 lute and related instruments. Here two examples. On the endpaper of an 18th century 5. V. Gigue 1’56 16. V. Menuet – Trio 2’37 lute manuscript now in the Bavarian State Library (Mus. Ms. 5362), the distich appears 17. VI. Gavotta 3’23 with the following introduction: Olim locuta Testudo – Once spoke the Lute. The same Anonym, Bratislava 18. VII. Menuet 3’34 distich appears as the motto of a book of tablature from the Hungarian monastery Suite in G 19. VIII. Finale 1’20 Marienthal; the introduction there, however, is different: Mandora olim locuta. Universitna Kniznica, Ms 1092 It almost seems like a competition, when two instruments of the lute family, the 6. I. Allegro 1’32 so-called Baroque lute and the mandora, both lay claim to an especially sweet sound. -

Die Laute in Europa 2 the Lute in Europe 2

Andreas Schlegel & Joachim Lüdtke Die Laute in Europa 2 Lauten, Gitarren, Mandolinen und Cistern The Lute in Europe 2 Lutes, Guitars, Mandolins, and Citterns Mitarbeiter: Pedro Caldeira Cabral: Guitarra Portuguesa Peter Forrester: Cittern Carlos Gonzalez: Vihuela de mano Lorenz Mühlemann: Schweizer Halszithern Pepe Rey: Bandurria Renzo Salvador: Baroque guitar Kenneth Sparr: Swedish lute Michael Treder: Lautenmusik der Habsburger Lande Roman Turovsky: Torban Contents A gallery of instruments 8 Which Instrument do you mean? 24 SYSTEMATIC SECTION Howdoes the lute work? 30 The hard work of redaiming old, lost knowledge 34 Lute building as the expression of an epoch's values 36 An example: The so-called "Presbyter lute" 38 Music and proportion 42 Commata- The System's bugs 46 Pythagorean and meantone tuning 48 Meantone and equal temperament 54 The crunch: The System offretting 58 Tablature - The notation of lute, guitar, and cittern 66 The interdependency of string material, string length and pitch 76 Developments in string making 80 ... and their consequences for lute building 86 The specification oftunings 92 HISTORICAL SECTION How to deal with history 94 Individual Instrument types The descant instruments ofthe lute familyand the mandolin 98 Colascione, Gallichon, Mandora 7 72 The Vihuela de mano (Carlos Gonzalez) 7 76 Renaissance and Baroque guitar (Renzo Salvador) 128 TheBandurria (Pepe Rey) 736 The Cittern family to 1700 (Peter Forrester) 744 The Cittern from the 18th Century to our days (Lorenz Mühlemann & Andreas Schlegel) .... 158 The fluorishing ofthe Halszither in Switzerland 764 Halszithers in Germany 764 The history of the Guitarra Portuguesa (Pedro Caldeira Cabral) 7 66 The Svenskiuta (Swedish lute or Swedish theorbo) (Kenneth Sparr) 7 76 The Torban (Roman Turovsky) 782 The History C. -

For Mandora the Harmony of Contrasts

forMusic Mandora Gábor Tokodi mandora Music for Mandora The Harmony of Contrasts Viva fui in sylvis Alive I was in the woods, Giuseppe Antonio Brescianello Anonym, Budapest tandem percussa securi Finally, though, the axe struck me. (1690-1757) Suite in C Viva nihil dixi Alive I spoke nothing, Sonata in G minor Egyetemi könyvtár, Ms. F 36 mortua dulce cano Dead I now sing sweetly. 1. I. Allegro 2’18 12. I. Capricio 1’41 2. II. Menuet – Trio 4’47 13. II. Alamand 1’57 This Latin distich, describing the transformation of a tree into a resonating body, was 3. III. Bourée 2’05 14. III. Allegro 1’41 commonplace from the 16th until the 18th century. Usually it was associated with the 4. IV. Menuet 1’19 15. IV. Aria 2’30 lute and related instruments. Here two examples. On the endpaper of an 18th century 5. V. Gigue 1’56 16. V. Menuet – Trio 2’37 lute manuscript now in the Bavarian State Library (Mus. Ms. 5362), the distich appears 17. VI. Gavotta 3’23 with the following introduction: Olim locuta Testudo – Once spoke the Lute. The same Anonym, Bratislava 18. VII. Menuet 3’34 distich appears as the motto of a book of tablature from the Hungarian monastery Suite in G 19. VIII. Finale 1’20 Marienthal; the introduction there, however, is different: Mandora olim locuta. Universitna Kniznica, Ms 1092 It almost seems like a competition, when two instruments of the lute family, the 6. I. Allegro 1’32 so-called Baroque lute and the mandora, both lay claim to an especially sweet sound. -

Library of Congress Medium of Performance Terms for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue anzhad USE clarinet BT double reed instrument USE imzad a-jaeng alghōzā Appalachian dulcimer USE ajaeng USE algōjā UF American dulcimer accordeon alg̲hozah Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE accordion USE algōjā dulcimer, American accordion algōjā dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, dulcimer, Kentucky garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. dulcimer, lap piano accordion UF alghōzā dulcimer, mountain BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah dulcimer, plucked NT button-key accordion algōzā Kentucky dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn mountain dulcimer accordion band do nally lap dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi plucked dulcimer with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī BT plucked string instrument UF accordion orchestra ngoze zither BT instrumental ensemble pāvā Appalachian mountain dulcimer accordion orchestra pāwā USE Appalachian dulcimer USE accordion band satāra arame, viola da acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute USE viola d'arame UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā arará folk bass guitar USE algōjā A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT guitar alpenhorn BT drum acoustic guitar USE alphorn arched-top guitar USE guitar alphorn USE guitar acoustic guitar, electric UF alpenhorn archicembalo USE electric guitar alpine horn USE arcicembalo actor BT natural horn archiluth An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE archlute required for the performance of a musical USE alphorn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic archiphone form. alto (singer) A microtonal electronic organ first built in 1970 in the Netherlands. BT performer USE alto voice adufo alto clarinet BT electronic organ An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE tambourine archlute associated with Western art music and is normally An extended-neck lute with two peg boxes that aenas pitched in E♭.