English Lute Manuscripts and Scribes 1530-1630

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

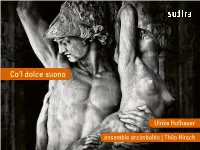

Digibooklet Co'l Dolche Suono

Co‘l dolce suono Ulrike Hofbauer ensemble arcimboldo | Thilo Hirsch JACQUES ARCADELT (~1507-1568) | ANTON FRANCESCO DONI (1513-1574) Il bianco e dolce cigno 2:35 Anton Francesco Doni, Dialogo della musica, Venedig 1544 Text: Cavalier Cassola, Diminutionen*: T. Hirsch FRANCESCO DE LAYOLLE (1492-~1540) Lasciar’ il velo 3:04 Giovanni Camillo Maffei, Delle lettere, [...], Neapel 1562 Text: Francesco Petrarca, Diminutionen: G. C. Maffei 1562 ADRIANO WILLAERT (~1490-1562) Amor mi fa morire 3:06 Il secondo Libro de Madrigali di Verdelotto, Venedig 1537 Text: Bonifacio Dragonetti, Diminutionen*: A. Böhlen SILVESTRO GANASSI (1492-~1565) Recercar Primo 0:52 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda pur della Prattica di Sonare il Violone d’Arco da Tasti, Venedig 1543 Recerchar quarto 1:15 Silvestro Ganassi, Regola Rubertina, Regola che insegna sonar de viola d’archo tastada de Silvestro Ganassi dal fontego, Venedig 1542 GIULIO SEGNI (1498-1561) Ricercare XV 5:58 Musica nova accomodata per cantar et sonar sopra organi; et altri strumenti, Venedig 1540, Diminutionen*: A. Böhlen SILVESTRO GANASSI Madrigal 2:29 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543 GIACOMO FOGLIANO (1468-1548) Io vorrei Dio d’amore 2:09 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543, Diminutionen*: T. Hirsch GIACOMO FOGLIANO Recercada 1:30 Intavolature manuscritte per organo, Archivio della parrochia di Castell’Arquato ADRIANO WILLAERT Ricercar X 5:09 Musica nova [...], Venedig 1540 Diminutionen*: Félix Verry SILVESTRO GANASSI Recercar Secondo 0:47 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543 SILVESTRO GANASSI Recerchar primo 0:47 Silvestro Ganassi, Regola Rubertina, Venedig 1542 JACQUES ARCADELT Quando co’l dolce suono 2:42 Il primo libro di Madrigali d’Arcadelt [...], Venedig 1539 Diminutionen*: T. -

Baroque Ensemble Program 12-6-18.Pdf

Our ensemble uses a set of baroque bows patterned after existing historic examples BYU – IDAHO DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC PRESENTS from the early 18th century. These bows are lighter, shorter, and have a slight outward curve resulting in characteristic baroque articulation -- a strong, quick down bow and a light, softer up bow, meant to emphasize the inequalities of strong and weak beats. Basso continuo refers to the preferred harmonic accompaniment used during the baroque era. From a printed bass line with a few harmonic clues indicated as numerical “figures,” musicians improvised chordal accompaniments which best fit the unique qualities of their instruments and supported the upper solo lines -- similar to the way a modern jazz rhythm section will “comp” behind a vocal or saxophone solo. This single bass line might include a colorful variety of both melodic and chord playing instruments. Tonight’s basso continuo section includes: • Harpsichord, featuring plucked brass strings across a light wood frame, resulting in a delicate, transparent tone which contrasts with the strong iron frame and hammered tone of the modern piano • Baroque style organ, using a mechanical “tracker” mechanism instead of electronics to route air to each pipe This evening’s performance features suites, sinfonia and concerti by prominent composers from the 17th and early 18th century: § The prolific Antonio Vivaldi is known for his development of three- movement concerto form. An extravagant violinist, he carried the nickname “il prete roso” (the red priest) because of his red hair. § Johann Heinrich Schmelzer was recognized in his day as Vienna's foremost violin virtuoso and a leading composer. -

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

High School Madrigals May 13, 2020

Concert Choir Virtual Learning High School Madrigals May 13, 2020 High School Concert Choir Lesson: May 13, 2020 Objective/Learning Target: students will learn about the history of the madrigal and listen to examples Bell Work ● Complete this google form. A Brief History of Madrigals ● 1501- music could be printed ○ This changed the game! ○ Reading music became expected ● The word “Madrigal” was first used in 1530 and was for musical settings of Italian poetry ● The Italian Madrigal became popular because the emphasis was on the meaning of the text through the music ○ It paved the way to opera and staged musical productions A Brief History of Madrigals ● Composers used text from popular poets at the time ● 1520-1540 Madrigals were written for SATB ○ At the time: ■ Cantus ■ Altus ■ Tenor ■ Bassus ○ More voices were added ■ Labeled by their Latin number ● Quintus (fifth voice) ● Sextus (sixth voice) ○ Originally written for 1 voice on a part A Brief History of Madrigals Homophony ● In the sixteenth century, instruments began doubling the voices in madrigals ● Madrigals began appearing in plays and theatre productions ● Terms to know: ○ Homophony: voices moving together with the same Polyphony rhythm ○ Polyphony: voices moving with independent rhythms ● Early madrigals were mostly homophonic and then polyphony became popular with madrigals A Brief History of Madrigals ● Jacques Arcadelt (1507-1568)was an Italian composer who used both homophony and polyphony in his madrigals ○ Il bianco e dolce cigno is a great example ● Cipriano de Rore -

The Implications of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study*

Performance Practice Review Volume 5 Article 2 Number 2 Fall The mplicI ations of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study Desmond Hunter Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Hunter, Desmond (1992) "The mpI lications of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 5: No. 2, Article 2. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199205.02.02 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol5/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Renaissance Keyboard Fingering The Implications of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study* Desmond Hunter The fingering of virginalist music has been discussed at length by various scholars.1 The topic has not been exhausted however; indeed, the views expressed and the conclusions drawn have all too frequently been based on limited evidence. I would like to offer some observations based on both a knowledge of the sources and the experience gained from applying the source fingerings in performances of the music. I propose to focus on two related aspects: the fingering of linear figuration and the fingering of graced notes. Our knowledge of English keyboard fingering is drawn from the information contained in virginalist sources. Fingerings scattered Revised version of a paper presented at the 25th Annual Conference of the Royal Musical Association in Cambridge University, April 1990. -

APPENDIX 1 Inventories of Sources of English Solo Lute Music

408/2 APPENDIX 1 Inventories of sources of English solo lute music Editorial Policy................................................................279 408/2.............................................................................282 2764(2) ..........................................................................290 4900..............................................................................294 6402..............................................................................296 31392 ............................................................................298 41498 ............................................................................305 60577 ............................................................................306 Andrea............................................................................308 Ballet.............................................................................310 Barley 1596.....................................................................318 Board .............................................................................321 Brogyntyn.......................................................................337 Cosens...........................................................................342 Dallis.............................................................................349 Danyel 1606....................................................................364 Dd.2.11..........................................................................365 Dd.3.18..........................................................................385 -

Some Products in This Line Do Not Bear the AP Seal. Product Categories Manufacturer/Company Name Brand Name Seal

# Some products in this line do not bear the AP Seal. Product Categories Manufacturer/Company Name Brand Name Seal Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Extra Strength School AP Glue Stick Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Gold Liner AP Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Silver Liner AP Adhesives, Glue New Port Sales, Inc. All Gloo CL Adhesives, Glue Leeho Co., Ltd. Leeho Window Paint Sparkler AP Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Xtreme School Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Newell Brands Elmer's Craftbond All-Temp Hot AP Glue Sticks Adhesives, Glue Daler-Rowney Limited Rowney Rabbit Skin AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Decoupage Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2 Way Glue AP Squeeze & Roll Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. Kuretake Oyatto-Nori AP Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2Way Glue AP Chisel Tip Adhesives, Glue Kuretake Co., Ltd. ZIG Memory System 2Way Glue AP Jumbo Tip Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts Fine-Tip AP Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts Wide-Tip AP Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue EK Success Martha Stewart Crafts AP Ballpoint-Tip Glue Pen Adhesives, Glue STAMPIN' UP Stampin' Up 2 Way Glue AP Adhesives, Glue Creative Memories Creative Memories Precision AP Point Adhesive Adhesives, Glue Rich Art Color Co., Inc. Rich Art Washable Bits & Pieces AP Glitter Glue Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. Best-Test One-Coat Cement CL Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. Best-Test Rubber Cement CL Adhesives, Glue Speedball Art Products Co. -

New Summary Report - 26 June 2015

New Summary Report - 26 June 2015 1. How did you find out about this survey? Other 17% Email from Renaissance Art 83.1% Email from Renaissance Art 83.1% 539 Other 17.0% 110 Total 649 1 2. Where are you from? Australia/New Zealand 3.2% Asia 3.7% Europe 7.9% North America 85.2% North America 85.2% 553 Europe 7.9% 51 Asia 3.7% 24 Australia/New Zealand 3.2% 21 Total 649 2 3. What is your age range? old fart like me 15.4% 21-30 22% 51-60 23.3% 31-40 16.8% 41-50 22.5% Statistics 21-30 22.0% 143 Sum 20,069.0 31-40 16.8% 109 Average 36.6 41-50 22.5% 146 StdDev 11.5 51-60 23.3% 151 Max 51.0 old fart like me 15.4% 100 Total 649 3 4. How many fountain pens are in your collection? 1-5 23.3% over 20 35.8% 6-10 23.9% 11-20 17.1% Statistics 1-5 23.3% 151 Sum 2,302.0 6-10 23.9% 155 Average 5.5 11-20 17.1% 111 StdDev 3.9 over 20 35.8% 232 Max 11.0 Total 649 4 5. How many pens do you usually keep inked? over 10 10.3% 7-10 12.6% 1-3 40.7% 4-6 36.4% Statistics 1-3 40.7% 264 Sum 1,782.0 4-6 36.4% 236 Average 3.1 7-10 12.6% 82 StdDev 2.1 over 10 10.3% 67 Max 7.0 Total 649 5 6. -

Download Booklet

572433bk Byrd EU_572433bk Byrd 21/07/2011 12:10 Page 4 notes, sometimes in two strands at once, against arrangement in Nevell. The noble final theme – the same counterpoints that seem a throwback to an earlier as that of the finest fugue in The Well-Tempered Clavier William generation. For that reason, most authorities consider – appears in doubled note values, wrought in Byrd’s this a youthful effort, but there is mastery here that goes most mature style. Here is what I think: this is Byrd’s far beyond Byrd’s early cantus firmus exercises in the memorial for Mary, Queen of Scots, and the BYRD style of Tallis and Blitheman. The notation in quarter- augmentation at the end is the prolongation of her line note (crotchet) beats, the division into clearly separated with her son James I, the ancestor of all subsequent variations, and the unique late source all point to this British monarchs.! Complete Fantasias for Harpsichord being the last of the fantasias!– Byrd, perhaps on a Byrd addressed a plea for careful execution of his winter’s night at Stondon Place, indulging in nostalgia works to “all true lovers of Musicke”, which closes thus: for the improvisational ecstasies of times past. “As I have done my best endeavor to give you content, so Glen Wilson The other hexachord piece # is the most modest I beseech you satisfie my desire in hearing them well and playful of the set. The theme in long single notes is expressed: and then I doubt not, for Art and Ayre both of to be played from beginning to end in the treble by a skillful and ignorant they will deserve liking. -

An Historical and Analytical Study of Renaissance Music for the Recorder and Its Influence on the Later Repertoire Vanessa Woodhill University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1986 An historical and analytical study of Renaissance music for the recorder and its influence on the later repertoire Vanessa Woodhill University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Woodhill, Vanessa, An historical and analytical study of Renaissance music for the recorder and its influence on the later repertoire, Master of Arts thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1986. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2179 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] AN HISTORICAL AND ANALYTICAL STUDY OF RENAISSANCE MUSIC FOR THE RECORDER AND ITS INFLUENCE ON THE LATER REPERTOIRE by VANESSA WOODHILL. B.Sc. L.T.C.L (Teachers). F.T.C.L A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the School of Creative Arts in the University of Wollongong. "u»«viRsmr •*"! This thesis is submitted in accordance with the regulations of the University of Wotlongong in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. I hereby certify that the work embodied in this thesis is the result of original research and has not been submitted for a higher degree at any other University or similar institution. Copyright for the extracts of musical works contained in this thesis subsists with a variety of publishers and individuals. Further copying or publishing of this thesis may require the permission of copyright owners. Signed SUMMARY The material in this thesis approaches Renaissance music in relation to the recorder player in three ways. -

Agnieszka Leszczyńska Uniwersytet Warszawski ————

ARTYKUŁY agnieszka leszczyńska uniwersytet warszawski ———— EMANUEL WURSTISEN, HIS TABLATURE AND LINKS TO POLAND LUTE MUSIC WITH MEDICINE IN THE BACKGROUND he lute tablature CH-Bu F IX 70, known as the Emanuel Wurstisen Lute T Book, has been kept at Basel University Library (Öffentliche Bibliothek der Universität Basel) since the early nineteenth century, but only became familiar to musicians and musicologists a little more than three decades ago, thanks to John Kmetz’s catalogue.1 A slightly modified and supplemented description of the tab- lature’s contents was soon presented by Christian Meyer.2 In 2012 Andreas Schlegel created a catalogue compiling data from both Kmetz and Meyer, and made it avail- able online, along with black and white reproductions of the manuscript, in eight volumes corresponding to the internal divisions found in the tablature.3 Later the entire digitalised source was made available online by Basel University Library.4 The repertoire contained in the tablature gradually attracted the interest of a growing number of musicologists and lutenists.5 One of the researchers who began to explore 1 John Kmetz, Die Handschriften der Universitätsbibliothek Basel: Katalog der Musikhandschriften des 16. Jahrhunderts: quellenkritische und historische Untersuchung, Basel 1988, pp. 206–229. 2 François-Pierre Goy, Christian Meyer and Monique Rollin (eds.), Sources manuscrites en tablature, luth et theorbe (c.1500–c.1800): Catalogue descriptif, vol. 1, Confoederatio Helvetica (CH), France (F), Baden-Baden 1991, pp. 1–27. 3 Andreas Schlegel (ed.), Basel, Öffentliche Bibliothek der Universität Basel, Musiksammlung (CH-Bu), Ms. F IX 70. Lautentabulatur, 1591 bis ca. 1594 in Basel geschrieben von Emanuel Wurstisen (1572–1619?) Bildteil.