Shiv Sena, Saamana, and Minorities Without Appendices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anthoney Udel 0060D

INCLUSION WITHOUT MODERATION: POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRATIC PARTICIPATION BY RELIGIOUS GROUPS by Cheryl Mariani Anthoney A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and International Relations Spring 2018 © 2018 Cheryl Anthoney All Rights Reserved INCLUSION WITHOUT MODERATION: POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRATIC PARTICIPATION BY RELIGIOUS GROUPS by Cheryl Mariani Anthoney Approved: __________________________________________________________ David P. Redlawsk, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Political Science and International Relations Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Ann L. Ardis, Ph.D. Senior Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Muqtedar Khan, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Stuart Kaufman, -

The Contest of Indian Secularism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto THE CONTEST OF INDIAN SECULARISM Erja Marjut Hänninen University of Helsinki Faculty of Social Sciences Political History Master’s thesis December 2002 Map of India I INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................1 PRESENTATION OF THE TOPIC ....................................................................................................................3 AIMS ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 SOURCES AND LITERATURE ......................................................................................................................7 CONCEPTS ............................................................................................................................................... 12 SECULARISM..............................................................................................................14 MODERNITY ............................................................................................................................................ 14 SECULARISM ........................................................................................................................................... 16 INDIAN SECULARISM .............................................................................................................................. -

Secrets of RSS

Secrets of RSS DEMYSTIFYING THE SANGH (The Largest Indian NGO in the World) by Ratan Sharda © Ratan Sharda E-book of second edition released May, 2015 Ratan Sharda, Mumbai, India Email:[email protected]; [email protected] License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-soldor given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person,please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and didnot purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to yourfavorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hardwork of this author. About the Book Narendra Modi, the present Prime Minister of India, is a true blue RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteers Organization) swayamsevak or volunteer. More importantly, he is a product of prachaarak system, a unique institution of RSS. More than his election campaigns, his conduct after becoming the Prime Minister really tells us how a responsible RSS worker and prachaarak responds to any responsibility he is entrusted with. His rise is also illustrative example of submission by author in this book that RSS has been able to design a system that can create ‘extraordinary achievers out of ordinary people’. When the first edition of Secrets of RSS was released, air was thick with motivated propaganda about ‘Saffron terror’ and RSS was the favourite whipping boy as the face of ‘Hindu fascism’. Now as the second edition is ready for release, environment has transformed radically. -

India's Democracy at 70: Toward a Hindu State?

India’s Democracy at 70: Toward a Hindu State? Christophe Jaffrelot Journal of Democracy, Volume 28, Number 3, July 2017, pp. 52-63 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2017.0044 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/664166 [ Access provided at 11 Dec 2020 03:02 GMT from Cline Library at Northern Arizona University ] Jaffrelot.NEW saved by RB from author’s email dated 3/30/17; 5,890 words, includ- ing notes. No figures; TXT created from NEW by PJC, 4/14/17 (4,446 words); MP ed- its to TXT by PJC, 4/19/17 (4,631 words). AAS saved by BK on 4/25/17; FIN created from AAS by PJC, 5/26/17 (5,018 words). FIN saved by BK on 5/2/17 (5,027 words); PJC edits as per author’s updates saved as FINtc, 6/8/17, PJC (5,308 words). PGS created by BK on 6/9/17. India’s Democracy at 70 TOWARD A HINDU STATE? Christophe Jaffrelot Christophe Jaffrelot is senior research fellow at the Centre d’études et de recherches internationales (CERI) at Sciences Po in Paris, and director of research at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS). His books include Religion, Caste, and Politics in India (2011). In 1976, India’s Constitution of 1950 was amended to enshrine secular- ism. Several portions of the original constitutional text already reflected this principle. Article 15 bans discrimination on religious grounds, while Article 25 recognizes freedom of conscience as well as “the right freely to profess, practise and propagate religion.” Collective as well as indi- vidual rights receive constitutional recognition. -

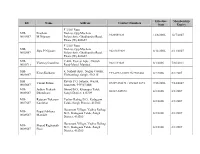

0001S07 Prashant M.Nijasure F 3/302 Rutu Enclave,Opp.Muchal

Effective Membership ID Name Address Contact Numbers from Expiry F 3/302 Rutu MH- Prashant Enclave,Opp.Muchala 9320089329 12/8/2006 12/7/2007 0001S07 M.Nijasure Polytechnic, Ghodbunder Road, Thane (W) 400607 F 3/302 Rutu MH- Enclave,Opp.Muchala Jilpa P.Nijasure 98210 89329 8/12/2006 8/11/2007 0002S07 Polytechnic, Ghodbunder Road, Thane (W) 400607 MH- C-406, Everest Apts., Church Vianney Castelino 9821133029 8/1/2006 7/30/2011 0003C11 Road-Marol, Mumbai MH- 6, Nishant Apts., Nagraj Colony, Kiran Kulkarni +91-0233-2302125/2303460 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0004S07 Vishrambag, Sangli, 416415 MH- Ravala P.O. Satnoor, Warud, Vasant Futane 07229 238171 / 072143 2871 7/15/2006 7/14/2007 0005S07 Amravati, 444907 MH MH- Jadhav Prakash Bhood B.O., Khanapur Taluk, 02347-249672 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0006S07 Dhondiram Sangli District, 415309 MH- Rajaram Tukaram Vadiye Raibag B.O., Kadegaon 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0007S07 Kumbhar Taluk, Sangli District, 415305 Hanamant Village, Vadiye Raibag MH- Popat Subhana B.O., Kadegaon Taluk, Sangli 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0008S07 Mandale District, 415305 Hanumant Village, Vadiye Raibag MH- Sharad Raghunath B.O., Kadegaon Taluk, Sangli 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0009S07 Pisal District, 415305 MH- Omkar Mukund Devrashtra S.O., Palus Taluk, 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0010S07 Vartak Sangli District, 415303 MH MH- Suhas Prabhakar Audumbar B.O., Tasgaon Taluk, 02346-230908, 09960195262 12/11/2007 12/9/2008 0011S07 Patil Sangli District 416303 MH- Vinod Vidyadhar Devrashtra S.O., Palus Taluk, 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0012S07 Gowande Sangli District, 415303 MH MH- Shishir Madhav Devrashtra S.O., Palus Taluk, 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0013S07 Govande Sangli District, 415303 MH Patel Pad, Dahanu Road S.O., MH- Mohammed Shahid Dahanu Taluk, Thane District, 11/24/2005 11/23/2006 0014S07 401602 3/4, 1st floor, Sarda Circle, MH- Yash W. -

Geological and Geomorphological Studies at Khadki Nala Basin, Mangalwedha Taluka, Solapur District, Maharashtra, India

International Journal of Engineering Technology Science and Research IJETSR www.ijetsr.com ISSN 2394 – 3386 Volume 4, Issue 9 September 2017 Geological and Geomorphological studies at Khadki Nala Basin, Mangalwedha Taluka, Solapur District, Maharashtra, India A. S Deshpande1 and A.B Narayanpethkar2 1 Civil Dept. KarmayogiEngineering Collage, Shelve,Pandharpur 2 School of Earth Science, Dept. of Applied Geology, Solapur University, Solapur ABSTRACT The linking of the geomorphological parameters and geology with the hydrological characteristics of the basin provides a simple way to understand the hydrologic behavior of the different basins particularly of the ungauged basin in hard rocks like Deccan basalt.Thetechniques of geomorphometric analysis are useful in the quantitative description of the geometry of the drainage basins and its network which helps in characterizing the drainage network. The geomorphological landforms are important from the hydrological point of view and include the linear, aerial and relief aspects of the drainage basin. It has also been found that hydrogeologicalgeomorphological investigations besides helping in targeting potential zones for groundwater exploration provides inputs towards estimation of the total groundwater resources in an area, the selection of appropriate sites for artificial recharge and the depth of the weathering. In present investigation KhadkiNala basin which falls geographically under Solapur district of Maharashtra, has been taken up for groundwater development. The area falls under the rain shadow zone and frequent drought is a common feature in the area due to adverse climatic conditions. Geologically the area falls under the hard rock terrain consisting of basaltic lava flows. Geology of KhadkiNala basin contain massive basalt, vesicular, weathered or zeolitic basalt and quaternary soil. -

E-Digest on Ambedkar's Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology

Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology An E-Digest Compiled by Ram Puniyani (For Private Circulation) Center for Study of Society and Secularism & All India Secular Forum 602 & 603, New Silver Star, Behind BEST Bus Depot, Santacruz (E), Mumbai: - 400 055. E-mail: [email protected], www.csss-isla.com Page | 1 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Preface Many a debates are raging in various circles related to Ambedkar’s ideology. On one hand the RSS combine has been very active to prove that RSS ideology is close to Ambedkar’s ideology. In this direction RSS mouth pieces Organizer (English) and Panchjanya (Hindi) brought out special supplements on the occasion of anniversary of Ambedkar, praising him. This is very surprising as RSS is for Hindu nation while Ambedkar has pointed out that Hindu Raj will be the biggest calamity for dalits. The second debate is about Ambedkar-Gandhi. This came to forefront with Arundhati Roy’s introduction to Ambedkar’s ‘Annihilation of Caste’ published by Navayana. In her introduction ‘Doctor and the Saint’ Roy is critical of Gandhi’s various ideas. This digest brings together some of the essays and articles by various scholars-activists on the theme. Hope this will help us clarify the underlying issues. Ram Puniyani (All India Secular Forum) Mumbai June 2015 Page | 2 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Contents Page No. Section A Ambedkar’s Legacy and RSS Combine 1. Idolatry versus Ideology 05 By Divya Trivedi 2. Top RSS leader misquotes Ambedkar on Untouchability 09 By Vikas Pathak 3. -

DEPARTMENT of MARATHI Faculty's of Marathi Department

DEPARTMENT OF MARATHI Faculty’s of Marathi Department Prof. Kalawati B. Mohod Dr. Prashant W. Dhanvij M.A.,B.Ed. M.A., M.Phil., Ph.D.(NET) Associate Professor Assistant Professor Date of Joining: 01 October 1992 Date of Joining: 14 January 2009 About Marathi Language Introduction Marathi is an Indo-Aryan language spoken predominantly by Marathi people of Maharashtra. It is the official language and co-official language in Maharashtra and Goa states of Western India respectively, and it is among the 23 official Languages of India. There were 73 million speakers in 2001; Marathi ranks 19th in the list of most spoken languages in the world. Marathi has the fourth largest number of native speakers in India. Marathi has some of the oldest literature of all modern Indo-Aryan languages, dating from about 900 AD. The major dialects of Marathi are Standard Marathi and the Varhadi dialect. There are other related languages such as Khandeshi, Dangi, Vadavali and Samavedi. Malvani Konkani has been heavily influenced by Marathi varieties. Geographic Distribution Marathi is primarily spoken in Maharashtra and parts of neighbouring states of Gujrat, Madhya Pradesh, Goa, Karnataka, Chhattisgarh and Andhra Pradesh, union-territories of Daman and Div and Dadra and Nagar Haveli. The cities of Baroda, Surat and Ahmedabad (Gujrat), Belgaum (Karnataka), Indore, Gwalior (Madhya Pradesh), Hydrabad and Tanjore (Tamil Nadu) each have sizable Marathi-speaking communities. Marathi is also spoken by Maharashtrian emigrants worldwide, especially in the United States, United Kingdom, Israel, Mauritius and Canada. Official Status Marathi is the official language of Maharashtra and co-official language in the union territories of Daman and Diu and Dadra and Nagar Haveli. -

Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2010 Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010) Elaisha Nandrajog Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Nandrajog, Elaisha, "Hindutva and Anti-Muslim Communal Violence in India Under the Bharatiya Janata Party (1990-2010)" (2010). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 219. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/219 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE HINDUTVA AND ANTI-MUSLIM COMMUNAL VIOLENCE IN INDIA UNDER THE BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY (1990-2010) SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR RODERIC CAMP AND PROFESSOR GASTÓN ESPINOSA AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY ELAISHA NANDRAJOG FOR SENIOR THESIS (Spring 2010) APRIL 26, 2010 2 CONTENTS Preface 02 List of Abbreviations 03 Timeline 04 Introduction 07 Chapter 1 13 Origins of Hindutva Chapter 2 41 Setting the Stage: Precursors to the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 3 60 Bharat : The India of the Bharatiya Janata Party Chapter 4 97 Mosque or Temple? The Babri Masjid-Ramjanmabhoomi Dispute Chapter 5 122 Modi and his Muslims: The Gujarat Carnage Chapter 6 151 Legalizing Communalism: Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (2002) Conclusion 166 Appendix 180 Glossary 185 Bibliography 188 3 PREFACE This thesis assesses the manner in which India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has emerged as the political face of Hindutva, or Hindu ethno-cultural nationalism. The insights of scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot, Ashish Nandy, Thomas Blom Hansen, Ram Puniyani, Badri Narayan, and Chetan Bhatt have been instrumental in furthering my understanding of the manifold elements of Hindutva ideology. -

Mahead-Dec2019.Pdf

MAHAPARINIRVAN DAY 550TH BIRTH ANNIVERSARY: GURU NANAK DEV CLIMATE CHANGE VS AGRICULTURE VOL.8 ISSUE 11 NOVEMBER–DECEMBER 2019 ` 50 PAGES 52 Prosperous Maharashtra Our Vision Pahawa Vitthal A Warkari couple wishes Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray after taking oath as the Chief Minister of Maharashtra. (Pahawa Vitthal is a pictorial book by Uddhav Thackeray depicting the culture and rural life of Maharashtra.) CONTENTS What’s Inside 06 THIS IS THE MOMENT The evening of the 28th November 2019 will be long remem- bered as a special evening in the history of Shivaji Park of Mumbai. The ground had witnessed many historic moments in the past with people thronging to listen to Shiv Sena Pramukh, Late Balasaheb Thackeray, and Udhhav Thackeray. This time, when Uddhav Thackeray took the oath as the Chief Minister of Maharashtra on this very ground, the entire place was once again charged with enthusiasm and emotions, with fulfilment seen in every gleaming eye and ecstasy on every face. Maharashtra Ahead brings you special articles on the new Chief Minister of Maharashtra, his journey as a politi- cian, the new Ministers, the State Government's roadmap to building New Maharashtra, and the newly elected members of the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly. 44 36 MAHARASHTRA TOURISM IMPRESSES THE BEACON OF LONDON KNOWLEDGE Maharashtra Tourism participated in the recent Bharat Ratna World Travel Market exhibition in London. A Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar platform to meet the world, the event helped believed that books the Department reach out to tourists and brought meaning to life. tourism-related professionals and inform them He had to suffer and about the tourism attractions and facilities the overcome acute sorrow State has. -

Narendra Modi Tops, Yogi Adityanath Enters List

Vol: 23 | No. 4 | April 2017 | R20 www.opinionexpress.in A MONTHLY NEWS MAGAZINE Hindu-Americans divided on Trump’s immigration policy COVER STORY SOARING HIGH The ties between India and Israel were never better The Pioneer Most Powerful Indians in 2017: Narendra Modi tops,OPINI YogiON EXPR AdityanathESS enters list 1 2 OPINION EXPRESS editorial Modi, Yogi & beyond RNI UP–ENG 70032/92, Volume 23, No 4 EDITOR Prashant Tewari – BJP is all set for the ASSOCiate EDITOR Dr Rahul Misra POLITICAL EDITOR second term in 2019 Prakhar Misra he surprise appointment of Yogi Adityanath as Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister post BUREAU CHIEF party’s massive victory in the recently concluded assembly elections indicates that Gopal Chopra (DELHI), Diwakar Shetty BJP/RSS are in mission mode for General Election 2019. The new UP CM will (MUMBAI), Sidhartha Sharma (KOLKATA), T ensure strict saffron legislation, compliance and governance to Lakshmi Devi (BANGALORE ) DIvyash Bajpai (USA), KAPIL DUDAKIA (UNITED KINGDOM) consolidate Hindutva forces. The eighty seats are vital to BJP’s re- Rajiv Agnihotri (MAURITIUS), Romil Raj election in the next parliament. PM Narendra Modi is world class Bhagat (DUBAI), Herman Silochan (CANADA), leader and he is having no parallel leader to challenge his suprem- Dr Shiv Kumar (AUS/NZ) acy in the country. In UP, poor Akhilesh and Rahul were just swept CONTENT partner aside-not by polarization, not by Hindu consolidation but simply by The Pioneer Modi’s far higher voltage personality. Pratham Pravakta However the elections in five states have proved that BJP is not LegaL AdviSORS unbeatable. -

Sindhi Community – Shiv Sena

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IND30284 Country: India Date: 4 July 2006 Keywords: India – Maharashtra – Sindhi Community – Shiv Sena This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Is there any independent information about any current ill-treatment of Sindhi people in Maharashtra state? 2. Is there any information about the authorities’ position on any ill-treatment of Sindhi people? RESPONSE 1. Is there any independent information about any current ill-treatment of Sindhi people in Maharashtra state? Executive Summary Information available on Sindhi websites, in press reports and in academic studies suggests that, generally speaking, the Sindhi community in Maharashtra state are not ill-treated. Most writers who address the situation of Sindhis in Maharashtra generally concern themselves with the social and commercial success which the Sindhis have achieved in Mumbai (where the greater part of the Sindh’s Hindu populace relocated after the partition of India and Pakistan). One news article was located which reported that the Sindhi community had been targeted for extortion, along with other “mercantile communities”, by criminal networks affiliated with Maharashtra state’s Sihiv Sena organisation.