India's Democracy at 70: Toward a Hindu State?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jaffrelothindu Nationalism and the Saffronisation of the Public Sphere

Contemporary South Asia ISSN: 0958-4935 (Print) 1469-364X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccsa20 Hindu nationalism and the ‘saffronisation of the public sphere’: an interview with Christophe Jaffrelot Edward Anderson & Christophe Jaffrelot To cite this article: Edward Anderson & Christophe Jaffrelot (2018) Hindu nationalism and the ‘saffronisation of the public sphere’: an interview with Christophe Jaffrelot, Contemporary South Asia, 26:4, 468-482, DOI: 10.1080/09584935.2018.1545009 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2018.1545009 Published online: 04 Dec 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 600 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ccsa20 CONTEMPORARY SOUTH ASIA 2018, VOL. 26, NO. 4, 468–482 https://doi.org/10.1080/09584935.2018.1545009 VIEWPOINT Hindu nationalism and the ‘saffronisation of the public sphere’:an interview with Christophe Jaffrelot Edward Andersona and Christophe Jaffrelotb aCentre of South Asian Studies, Department of Politics and International Studies, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland; bCentre de Recherches Internationales, Sciences Po, Paris, France ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This in-depth interview with Professor Christophe Jaffrelot – one of the Nationalism; Hindutva; Hindu world’s most distinguished, prolific, and versatile scholars of nationalism; Indian politics; contemporary South Asia – focuses on his first area of expertise: Democracy Hindutva and the Hindu nationalist movement. In conversation with Dr Edward Anderson, Jaffrelot considers the development of Hindutva in India up to the present day, in particular scrutinising ways in which it has evolved over the past three decades. -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction The Invention of an Ethnic Nationalism he Hindu nationalist movement started to monopolize the front pages of Indian newspapers in the 1990s when the political T party that represented it in the political arena, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP—which translates roughly as Indian People’s Party), rose to power. From 2 seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian parliament, the BJP increased its tally to 88 in 1989, 120 in 1991, 161 in 1996—at which time it became the largest party in that assembly—and to 178 in 1998. At that point it was in a position to form a coalition government, an achievement it repeated after the 1999 mid-term elections. For the first time in Indian history, Hindu nationalism had managed to take over power. The BJP and its allies remained in office for five full years, until 2004. The general public discovered Hindu nationalism in operation over these years. But it had of course already been active in Indian politics and society for decades; in fact, this ism is one of the oldest ideological streams in India. It took concrete shape in the 1920s and even harks back to more nascent shapes in the nineteenth century. As a movement, too, Hindu nationalism is heir to a long tradition. Its main incarnation today, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS—or the National Volunteer Corps), was founded in 1925, soon after the first Indian communist party, and before the first Indian socialist party. -

Amit Shah at Parivartan Yatra Rally in Mysore

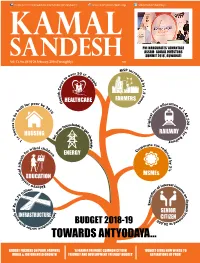

https://www.facebook.com/Kamal.Sandesh/ www.kamalsandesh.org @kamalsandeshbjp PM INAUGURAtes ‘ADVANTAGE ASSAM- GLOBAL INVESTORS SUMMit 2018’, GUWAHATI Vol. 13, No. 04 16-28 February, 2018 (Fortnightly) `20 HEALTHCARE FARMERS HOUSING RAILWAY ENERGY MSMEs EDUCATION SENIOR INFRASTRUCTURE BUDGET 2018-19 CITIZEN TOWARDS ANTYODAYA... BUDGET FOCUSES ON POOR, FARMERS ‘A FARMER FRIENDLY, COMMON CITIZEN ‘BUDGET GIVES NEW WINGS TO RURAL & JOB ORIENTED GROWTH FRIENDLY AND DEVELOPMENT FRIENDLY BUDGEt’ 16-28 FEBRUARY,ASP IRATIONS2018 I KAMAL OF P SANDESHoor’ I 1 Karnataka BJP welcomes BJP National President Shri Amit Shah at Parivartan Yatra Rally in Mysore. BJP National President Shri Amit Shah hoisting the tri-colour on the 69th Republic Day celebration at BJP HQ, New Delhi. BJP National President Shri Amit Shah paying floral tributes Shri Amit Shah addressing the SARBANSDANI to to Sant Ravidas ji on his Jayanti at BJP H.Q. in New Delhi commemorate the 350th birth anniversary of Guru Gobind 2 I KAMAL SANDESH I 16-28 FEBRUARY, 2018 Singh ji at Chandani Chowk, New Delhi. Fortnightly Magazine Editor Prabhat Jha Executive Editor Dr. Shiv Shakti Bakshi Associate Editors Ram Prasad Tripathy Vikash Anand Creative Editors Vikas Saini Mukesh Kumar Phone +91(11) 23381428 FAX +91(11) 23387887 BUDGET FOCUSES ON POOR, FARMERS RURAL & JOB E-mail ORIENTED GROWTH [email protected] Finance Minister Shri Arun Jaitley presented on February 1, 2018 general [email protected] 06 Budget 2018-19 in Parliament. It was second time the budget was Website: www.kamalsandesh.org presented on first of February instead following colonial era practices of... VAICHARIKI 17 C M SIDDARAMAIAH SYNONYMOUS WITH Aspects of Economics 21 CORRUPTION: AMIT SHAH BJP National President Shri SHRADHANJALI Amit Shah said Karnataka CM Siddaramaiah was synonymous Chintaman Vanga / Hukum Singh 23 with corruption and added 15 CONGRESS GOVERNMENT that the state government was ARTICLE IN KARNATAKA IS ON EXIT protecting the killers of Hindu.. -

Mahead-Dec2019.Pdf

MAHAPARINIRVAN DAY 550TH BIRTH ANNIVERSARY: GURU NANAK DEV CLIMATE CHANGE VS AGRICULTURE VOL.8 ISSUE 11 NOVEMBER–DECEMBER 2019 ` 50 PAGES 52 Prosperous Maharashtra Our Vision Pahawa Vitthal A Warkari couple wishes Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray after taking oath as the Chief Minister of Maharashtra. (Pahawa Vitthal is a pictorial book by Uddhav Thackeray depicting the culture and rural life of Maharashtra.) CONTENTS What’s Inside 06 THIS IS THE MOMENT The evening of the 28th November 2019 will be long remem- bered as a special evening in the history of Shivaji Park of Mumbai. The ground had witnessed many historic moments in the past with people thronging to listen to Shiv Sena Pramukh, Late Balasaheb Thackeray, and Udhhav Thackeray. This time, when Uddhav Thackeray took the oath as the Chief Minister of Maharashtra on this very ground, the entire place was once again charged with enthusiasm and emotions, with fulfilment seen in every gleaming eye and ecstasy on every face. Maharashtra Ahead brings you special articles on the new Chief Minister of Maharashtra, his journey as a politi- cian, the new Ministers, the State Government's roadmap to building New Maharashtra, and the newly elected members of the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly. 44 36 MAHARASHTRA TOURISM IMPRESSES THE BEACON OF LONDON KNOWLEDGE Maharashtra Tourism participated in the recent Bharat Ratna World Travel Market exhibition in London. A Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar platform to meet the world, the event helped believed that books the Department reach out to tourists and brought meaning to life. tourism-related professionals and inform them He had to suffer and about the tourism attractions and facilities the overcome acute sorrow State has. -

Written Testimony of Musaddique Thange Communications Director Indian American Muslim Council (IAMC)

Written Testimony of Musaddique Thange Communications Director Indian American Muslim Council (IAMC) for ‘Challenges & Opportunities: The Advancement of Human Rights in India’ by Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission June 7, 2016 1334 Longworth House Office Building Challenges & Opportunities: The Advancement of Human Rights in India Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission - June 7, 2016 Table of Contents Table of Contents Introduction Religious violence, hate speeches and other forms of persecution The Hindu Nationalist Agenda Religious Violence Hate / Provocative speeches Cow related violence - killing humans to protect cows Ghar Wapsi and the Business of Forced and Fraudulent Conversions Love Jihad Counter-terror Scapegoating of Impoverished Muslim Youth Curbs on Religious Freedoms of Minorities Caste based reservation only for Hindus; Muslims and Christians excluded No distinct identity for Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains Anti-Conversion Laws and the Hindu Nationalist Agenda A Broken and Paralyzed Judiciary Myth of a functioning judiciary Frivolous cases and abuse of judicial process Corruption in the judiciary Destruction of evidence Lack of constitutional protections Recommendations US India Strategic Dialogue Human Rights Workers’ Exchange Program USCIRF’s Assessment of Religious Freedom in India Conclusion Appendix A: Hate / Provocative speeches MP Yogi Adityanath (BJP) MP Sakshi Maharaj (BJP) Sadhvi Prachi Arya Sadhvi Deva Thakur Baba Ramdev MP Sanjay Raut (Shiv Sena) Written Testimony - Musaddique Thange (IAMC) 1 / 26 Challenges & Opportunities: The Advancement of Human Rights in India Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission - June 7, 2016 Introduction India is a multi-religious, multicultural, secular nation of nearly 1.25 billion people, with a long tradition of pluralism. It’s constitution guarantees equality before the law, and gives its citizens the right to profess, practice and propagate their religion. -

Government of India Ministry of External Affairs Rajya

01/06/2019 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS RAJYA SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO-2568 ANSWERED ON-09.08.2018 Permission for State Ministers to visit China 2568 Shri Ritabrata Banerjee . (a) whether it is a fact that Government is not allowing elected Chief Ministers and other Cabinet Ministers of State Governments to go on a visit to China; (b) if so, the details thereof, State-wise and if not, the reasons therefor; and (c) the details of Chief Ministers and other State Ministers visiting China during the last three years? ANSWER (a) to (c) There are no restrictions on the travel of Chief Ministers and Ministers of State Governments to the People’s Republic of China. On the contrary, under an institutional arrangement between Ministry of External Affairs and the International Department of the Communist Party of China, visits of Chief Ministers of Indian States to China are proactively facilitated in order to promote contacts at the level of provincial leaders and with senior functionaries of the Communist Party of China. Among the Chief Ministers and Ministers of our States, who have visited China since 2015, include: Chief Ministers: S. No. State Minister Period of Visit 1. Andhra Pradesh Shri N. Chandrababu Naidu April 2015 2. Gujarat Smt. Anandiben Patel May 2015 3. Maharashtra Shri Devendra Fadnavis May 2015 4. Telangana Shri K. Chandrashekhar Rao September 2015 5. Haryana Shri Manohar Lal Khattar January 2016 6. Chhattisgarh Shri Raman Singh April 2016 7. Andhra Pradesh Shri N. Chandrababu Naidu June 2016 8. Madhya Pradesh Shri Shivraj Singh Chouhan June 2016 Ministers of States: S. -

'Ambedkar's Constitution': a Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Caste

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 2 No. 1 pp. 109–131 brandeis.edu/j-caste April 2021 ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v2i1.282 ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution’: A Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Caste Discourse? Anurag Bhaskar1 Abstract During the last few decades, India has witnessed two interesting phenomena. First, the Indian Constitution has started to be known as ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution’ in popular discourse. Second, the Dalits have been celebrating the Constitution. These two phenomena and the connection between them have been understudied in the anti-caste discourse. However, there are two generalised views on these aspects. One view is that Dalits practice a politics of restraint, and therefore show allegiance to the Constitution which was drafted by the Ambedkar-led Drafting Committee. The other view criticises the constitutional culture of Dalits and invokes Ambedkar’s rhetorical quote of burning the Constitution. This article critiques both these approaches and argues that none of these fully explores and reflects the phenomenon of constitutionalism by Dalits as an anti-caste social justice agenda. It studies the potential of the Indian Constitution and responds to the claim of Ambedkar burning the Constitution. I argue that Dalits showing ownership to the Constitution is directly linked to the anti-caste movement. I further argue that the popular appeal of the Constitution has been used by Dalits to revive Ambedkar’s legacy, reclaim their space and dignity in society, and mobilise radically against the backlash of the so-called upper castes. Keywords Ambedkar, Constitution, anti-caste movement, constitutionalism, Dalit Introduction Dr. -

Muslims in India: Sciences Po, Princeton and Columbia Launch New Research with the Support of the Henry Luce Foundation

Muslims in India: Sciences Po, Princeton and Columbia launch new research with the support of the Henry Luce Foundation The Universities of Sciences Po, Princeton and Columbia are launching a major three-year research project on Muslim communities in India thanks to the generous support of the Henry Luce Foundation. This project was jointly developed by Christophe Jaffrelot, Professor at Sciences Po and CERI- CNRS Senior Research Fellow and a leading scholar of India, along with Bernard Haykel, Professor of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University and a scholar of Islam and the Middle East. The resulting research will offer new analysis and insights into the challenges faced by Muslim communities in India today. Bringing together a community of over 30 scholars and researchers in India, the United States, France and the UK, the project will provide a detailed examination of the multiple factors impacting Indian Muslim communities and shaping their future. Manan Ahmed, Associate Professor in the Department of History at Columbia University, and a specialist in the history of South Asia, will lead the development of visualization and spatial mapping highlighting the results of the research. The US Sciences Po Foundation and the Alliance Program are also key partners of this project. Christophe Jaffrelot said: “India has inherited a rich civilization to which the Muslim community has contributed in many different ways. Indian Muslims are facing the same challenges as many other minorities in the world. In order to analyze their condition in cultural, educational, sociological, economic and political terms, our team will systematically promote a mixed research method combining ethnographic fieldwork and survey-based data collection, at all levels – local, regional and national – and in urban as well as rural contexts. -

Seats (Won by BJP in 2014 LS Elections) Winner BJP Candidate (2014 LS Election UP) Votes for BJP Combined Votes of SP and BSP Vo

Combined Seats (Won By BJP in Winner BJP Candidate (2014 LS Election Votes for Votes of SP Vote 2014 LS Elections) UP) BJP and BSP Difference Saharanpur RAGHAV LAKHANPAL 472999 287798 185201 Kairana HUKUM SINGH 565909 489495 76414 Muzaffarnagar (DR.) SANJEEV KUMAR BALYAN 653391 413051 240340 Bijnor KUNWAR BHARTENDRA 486913 511263 -24350 Nagina YASHWANT SINGH 367825 521120 -153295 Moradabad KUNWER SARVESH KUMAR 485224 558665 -73441 Rampur DR. NEPAL SINGH 358616 491647 -133031 Sambhal SATYAPAL SINGH 360242 607708 -247466 Amroha KANWAR SINGH TANWAR 528880 533653 -4773 Meerut RAJENDRA AGARWAL 532981 512414 20567 Baghpat DR. SATYA PAL SINGH 423475 355352 68123 Ghaziabad VIJAY KUMAR SINGH 758482 280069 478413 Gautam Buddha 517727 81975 Nagar DR.MAHESH SHARMA 599702 Bulandshahr BHOLA SINGH 604449 311213 293236 Aligarh SATISH KUMAR 514622 454170 60452 Hathras RAJESH KUMAR DIWAKER 544277 398782 145495 Mathura HEMA MALINI 574633 210245 364388 Agra DR. RAM SHANKAR KATHERIA 583716 418161 165555 Fatehpur Sikri BABULAL 426589 466880 -40291 Etah RAJVEER SINGH (RAJU BHAIYA) 474978 411104 63874 Aonla DHARMENDRA KUMAR 409907 461678 -51771 Bareilly SANTOSH KUMAR GANGWAR 518258 383622 134636 Pilibhit MANEKA SANJAY GANDHI 546934 436176 110758 Shahjahanpur KRISHNA RAJ 525132 532516 -7384 Kheri AJAY KUMAR 398578 448416 -49838 Dhaurahra REKHA 360357 468714 -108357 Sitapur RAJESH VERMA 417546 522689 -105143 Hardoi ANSHUL VERMA 360501 555701 -195200 Misrikh ANJU BALA 412575 519971 -107396 Unnao SWAMI SACHCHIDANAND HARI SAKSHI 518834 408837 109997 Mohanlalganj -

YEARS of India Rebuilding

PM NAGPUR VISIT n DIALOGUE: CHIEF MINISTER n NITI AAYOG MEETING n ASIATIC SOCIETY VOL.6 ISSUE 05 n M AY 2017 n `50 n PAGES 52 YEARS OF REBUILDING INDIA PRIORITY Maharashtra A TRUSTED DESTINATION Prime Minister Narendra Modi has made all efforts to focus on the development of Maharashtra. The State has not just got support from him, but has also been a platform to launch and celebrate his initiatives 1 2 3 4 5 1. Prime Minister Narendra Modi performing jalpoojan of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj memorial; 2. The Prime Minister with Pune girl Vaishali Yadav; 3. The Prime Minister at the Make in India Week; 4. The Prime Minister with Governor Ch. Vidyasagar Rao, Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis and other dignitaries at the Smart Cities function in Pune; 5. The Prime Minister inaugurates GE facility at Chakan; 6. The Prime Minister at the signing of MIDC and TwinStar Display Technologies MoU; 7. The Prime Minister performing bhoomipujan of Dr 6 Ambedkar memorial at Indu Mill 7 CONTENTS What’s Inside 05 Column DEVENDRA FADNAVIS The Chief Minister of Maharashtra writes on the three years of the Union Government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. In these three years, the country has steadily transformed into a nation that is competent, enabled and fully geared to face challenges confidently and emerge as a global power. The time was also good for States like Maharashtra that recieved immense support, guidance, global opportunities and welfare programmes dedicated to various sections to build an inclusive society 09 COLUMN 12 COLUMN 14 COLUMN -

Violence and Discrimination Against India's Religious Minorities

briefing A Narrowing Space: Violence and discrimination against India's religious minorities Center for Study of Society and Secularism & Minority Rights Group International Friday prayer at the Jama Masjid, New Delhi. Mays Al-Juboori. Acknowledgements events. Through these interventions we seek to shape public This report has been produced with the assistance of the opinion and influence policies in favor of stigmatized groups. Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. In recognition of its contribution to communal harmony, CSSS The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of was awarded the Communal Harmony award given by the Minority Rights Group International and the Center for Study Ministry of Home Affairs in 2015. of Society and Secularism, and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Swedish International Development Minority Rights Group International Cooperation Agency. Minority Rights Group International (MRG) is a non-governmental organization (NGO) working to secure the rights of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and indigenous peoples worldwide, and to promote cooperation and understanding between communities. Our activities are focused on international advocacy, training, publishing and outreach. We are guided by the needs expressed by our worldwide partner network of organizations, which represent Center for Study of Society and Secularism minority and indigenous peoples. The Centre for Study of Society and Secularism (CSSS) is a non profit organization founded in 1993 by the celebrated MRG works with over 150 organizations in nearly 50 Islamic scholar Dr. Asghar Ali Engineer. CSSS works in countries. Our governing Council, which meets twice a different states of India. CSSS works for the rights of the year, has members from 10 different countries. -

Assimilation in a Postcolonial Context: the Hindu Nationalist Discourse on Westernization

Sylvie Guichard Assimilation in a Postcolonial Context: the Hindu Nationalist Discourse on Westernization Just a few days after the brutal rape of a 23 year-old woman in Delhi in December 2012, Mohan Bhagwat, chief of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the Hindu nationalist outfit at the heart of the Hindu nationalist move- ment declared: „Crimes against women happening in urban India are shame- ful. It is a dangerous trend. But such crimes won’t happen in Bharat or the rural areas of the country. You go to villages and forests of the country and there will be no such incidents of gangrape or sex crimes […]. Where ‚Bharat‘ becomes ‚India‘ with the influence of western culture, these types of incidents happen. The actual Indian values and culture should be established at every stratum of society where women are treated as ‚mother‘.“1 We see here a central theme of the Hindu nationalist discourse: a traditional Bharat (the Sanskrit name for the Indian subcontinent), a Hindu India, en- dangered by westernization and opposed to an already westernized India. This chapter explores this discourse on westernization: What does it mean for the Hindu nationalist movement? How does this movement speaks about west- ernization? And how has this discourse developed over time? The argument put forth has three parts (corresponding to the three sections of this chapter). We will see first that westernization can be considered as a form of feared or felt assimilation to a dominant, hegemonic, non-national cul- ture, or maybe, rather, to an imagined Western way of life (what some authors have called Occidentalism2); second that a form of chosen westernization is practiced in the Hindu nationalist movement as a strategy of „resistance by imitation“ in parallel with a discourse of „feared assimilation“; and third that when this discourse is applied to women and sexuality, it offers a meeting 1 Hindustan Times, „Rapes occur in ‚India‘, not in ‚Bharat‘: RSS chief“, 4 January 2013.