The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract. -

The Romanization of Attic Ritual Space in the Age of Augustus

The Romanization of Attic Ritual Space in the Age of Augustus Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Benavides, Makayla Lorraine Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 14:30:47 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/633170 THE ROMANIZATION OF ATTIC RITUAL SPACE IN THE AGE OF AUGUSTUS by Makayla Benavides ____________________________ Copyright © Makayla Benavides 2019 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES AND CLASSICS In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 1 7 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Master's Committee, we certify that we have read the thesis prepared by Makayla Benavides titled The Romanizationof Attic Ritual Space in the Age ofAugustus and recommend that it be accepted as fulfillingthe dissertation requirement for the Master's Degree. Date: .r- / - :.?CJ/ 5f David Soren Date: S - I - 2..o I � Mary E Voyatzis David Gilman Romano Date: ----- [Committee Member Name} Final approval and acceptance of this thesis is contingent upon the candidate's submission of the final copies of the thesis to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this thesis prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfillingthe Master's requirement. -

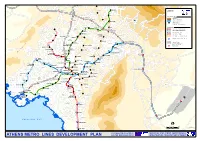

Athens Metro Lines Development Plan and the European Union Transport and Networks

Kifissia M t . P e Zefyrion Lykovrysi KIFISSIA n t LEGEND e l i Metamorfosi KAT METRO LINES NETWORK Operating Lines Pefki Nea Penteli LINE 1 Melissia PEFKI LINE 2 Kamatero MAROUSSI LINE 3 Iraklio Extensions IRAKLIO Penteli LINE 3, UNDER CONSTRUCTION NERANTZIOTISSA OTE AG.NIKOLAOS Nea LINE 2, UNDER DESIGN Filadelfia NEA LINE 4, UNDER DESIGN IONIA Maroussi IRINI PARADISSOS Petroupoli Parking Facility - Attiko Metro Ilion PEFKAKIA Nea Vrilissia Ionia ILION Aghioi OLYMPIAKO "®P Operating Parking Facility STADIO Anargyri "®P Scheduled Parking Facility PERISSOS Nea PALATIANI Halkidona SUBURBAN RAILWAY NETWORK SIDERA Suburban Railway DOUK.PLAKENTIAS Anthousa ANO Gerakas PATISSIA Filothei "®P Suburban Railway Section also used by Metro o Halandri "®P e AGHIOS HALANDRI l P "® ELEFTHERIOS ALSOS VEIKOU Kallitechnoupoli a ANTHOUPOLI Galatsi g FILOTHEI AGHIA E KATO PARASKEVI PERISTERI GALATSI Aghia . PATISSIA Peristeri P Paraskevi t Haidari Psyhiko "® M AGHIOS NOMISMATOKOPIO AGHIOS Pallini ANTONIOS NIKOLAOS Neo PALLINI Pikermi Psihiko HOLARGOS KYPSELI FAROS SEPOLIA ETHNIKI AGHIA AMYNA P ATTIKI "® MARINA "®P Holargos DIKASTIRIA Aghia PANORMOU ®P KATEHAKI Varvara " EGALEO ST.LARISSIS VICTORIA ATHENS ®P AGHIA ALEXANDRAS " VARVARA "®P ELEONAS AMBELOKIPI Papagou Egaleo METAXOURGHIO OMONIA EXARHIA Korydallos Glyka PEANIA-KANTZA AKADEMIA GOUDI Nera "®P PANEPISTIMIO MEGARO MONASTIRAKI KOLONAKI MOUSSIKIS KORYDALLOS KERAMIKOS THISSIO EVANGELISMOS ZOGRAFOU Nikea SYNTAGMA ANO ILISSIA Aghios PAGRATI KESSARIANI Ioannis ACROPOLI NEAR EAST Rentis PETRALONA NIKEA Tavros Keratsini Kessariani SYGROU-FIX KALITHEA TAVROS "®P NEOS VYRONAS MANIATIKA Spata KOSMOS Pireaus AGHIOS Vyronas s MOSCHATO Peania IOANNIS o Dafni t Moschato Ymittos Kallithea ANO t Drapetsona i PIRAEUS DAFNI ILIOUPOLI FALIRO Nea m o Smyrni Y o Î AGHIOS Ilioupoli DIMOTIKO DIMITRIOS . -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials Figure S1. Temperature‐mortality association by sector, using the E‐OBS data. Municipality ES (95% CI) CENTER Athens 2.95 (2.36, 3.54) Subtotal (I-squared = .%, p = .) 2.95 (2.36, 3.54) . EAST Dafni-Ymittos 0.56 (-1.74, 2.91) Ilioupoli 1.42 (-0.23, 3.09) Kessariani 2.91 (0.39, 5.50) Vyronas 1.22 (-0.58, 3.05) Zografos 2.07 (0.24, 3.94) Subtotal (I-squared = 0.0%, p = 0.689) 1.57 (0.69, 2.45) . NORTH Aghia Paraskevi 0.63 (-1.55, 2.87) Chalandri 0.87 (-0.89, 2.67) Galatsi 1.71 (-0.57, 4.05) Gerakas 0.22 (-4.07, 4.70) Iraklio 0.32 (-2.15, 2.86) Kifissia 1.13 (-0.78, 3.08) Lykovrisi-Pefki 0.11 (-3.24, 3.59) Marousi 1.73 (-0.30, 3.81) Metamorfosi -0.07 (-2.97, 2.91) Nea Ionia 2.58 (0.66, 4.54) Papagos-Cholargos 1.72 (-0.36, 3.85) Penteli 1.04 (-1.96, 4.12) Philothei-Psychiko 1.59 (-0.98, 4.22) Vrilissia 0.60 (-2.42, 3.71) Subtotal (I-squared = 0.0%, p = 0.975) 1.20 (0.57, 1.84) . PIRAEUS Aghia Varvara 0.85 (-2.15, 3.94) Keratsini-Drapetsona 3.30 (1.66, 4.97) Korydallos 2.07 (-0.01, 4.20) Moschato-Tavros 1.47 (-1.14, 4.14) Nikea-Aghios Ioannis Rentis 1.88 (0.39, 3.39) Perama 0.48 (-2.43, 3.47) Piraeus 2.60 (1.50, 3.71) Subtotal (I-squared = 0.0%, p = 0.580) 2.25 (1.58, 2.92) . -

Villa Karissa

LuxuryVilla Villa inKarissa Zakynthos Greece Welcome Set amongst the olive groves in the tiny village of GERAKAS, to the south of the island of ZAKYNTHOS ZANTE, GREECE, is the three bedroom stone built Villa Karissa. It is available for holiday rental from May to October from just £520 per week. A five five minute walk to local shops, tavernas, the turtle research centre and the delightful Gerakas secluded and sandy beach. The town of Zante and its fishing port is just a 30 minute drive away It is the perfect place for a relaxing & peaceful holiday, exclusively yours for the duration of your stay. We are not a package holiday company, this is our own private villa, so you have to book your own flights from whatever airport you prefer and at times that suit you. Whilst we leave you alone while you're on holiday in our villa you're not totally abandoned as we do have our representatives to sort out any problems should they occur and to advise on excursions, car hire and local amenities should you need them to The villa itself is 148sqm and the surrounding private garden is 1500sqm. The freshwater swimming pool is 8m x 3.5m and because the villa is south facing it captures the sunlight from dawn to dusk. Each room has its own superb view of either olive groves, mountain area or the Ionian Sea with views of surrounding Greek Islands. Boat trips and excursions are available locally to tour the island of Zante and ferry's to take you to Kafelonia or the Peloponnese Islands. -

Athens Metro Lines Development Plan and the European Union Infrastructure, Transport and Networks

AHARNAE Kifissia M t . P ANO Lykovrysi KIFISSIA e LIOSIA Zefyrion n t LEGEND e l i Metamorfosi KAT OPERATING LINES METAMORFOSI Pefki Nea Penteli LINE 1, ISAP IRAKLIO Melissia LINE 2, ATTIKO METRO LIKOTRIPA LINE 3, ATTIKO METRO Kamatero MAROUSSI METRO STATION Iraklio FUTURE METRO STATION, ISAP Penteli IRAKLIO NERATZIOTISSA OTE EXTENSIONS Nea Filadelfia LINE 2, UNDER CONSTRUCTION KIFISSIAS NEA Maroussi LINE 3, UNDER CONSTRUCTION IRINI PARADISSOS Petroupoli IONIA LINE 3, TENDERED OUT Ilion PEFKAKIA Nea Vrilissia LINE 2, UNDER DESIGN Ionia Aghioi OLYMPIAKO PENTELIS LINE 4, UNDER DESIGN & TENDERING AG.ANARGIRI Anargyri STADIO PERISSOS Nea "®P PARKING FACILITY - ATTIKO METRO Halkidona SIDERA DOUK.PLAKENTIAS Anthousa Suburban Railway Kallitechnoupoli ANO Gerakas PATISSIA Filothei Halandri "®P o ®P Suburban Railway Section " Also Used By Attiko Metro e AGHIOS HALANDRI l "®P ELEFTHERIOS ALSOS VEIKOU Railway Station a ANTHOUPOLI Galatsi g FILOTHEI AGHIA E KATO PARASKEVI PERISTERI . PATISSIA GALATSI Aghia Peristeri THIMARAKIA P Paraskevi t Haidari Psyhiko "® M AGHIOS NOMISMATOKOPIO AGHIOS Pallini NIKOLAOS ANTONIOS Neo PALLINI Pikermi Psihiko HOLARGOS KYPSELI FAROS SEPOLIA ETHNIKI AGHIA AMYNA P ATTIKI "® MARINA "®P Holargos DIKASTIRIA Aghia PANORMOU ®P ATHENS KATEHAKI Varvara " EGALEO ST.LARISSIS VICTORIA ATHENS ®P AGHIA ALEXANDRAS " VARVARA "®P ELEONAS AMBELOKIPI Papagou Egaleo METAXOURGHIO OMONIA EXARHIA Korydallos Glyka PEANIA-KANTZA AKADEMIA GOUDI Nera PANEPISTIMIO KERAMIKOS "®P MEGARO MONASTIRAKI KOLONAKI MOUSSIKIS KORYDALLOS ZOGRAFOU THISSIO EVANGELISMOS Zografou Nikea ROUF SYNTAGMA ANO ILISSIA Aghios KESSARIANI PAGRATI Ioannis ACROPOLI Rentis PETRALONA NIKEA Tavros Keratsini Kessariani RENTIS SYGROU-FIX P KALITHEA TAVROS "® NEOS VYRONAS MANIATIKA Spata KOSMOS LEFKA Pireaus AGHIOS Vyronas s MOSHATO IOANNIS o Peania Dafni t KAMINIA Moshato Ymittos Kallithea t Drapetsona PIRAEUS DAFNI i FALIRO Nea m o Smyrni Y o Î AGHIOS Ilioupoli DIMOTIKO DIMITRIOS . -

Implementation of Noise Barriers in Attiki Odos Motorway Based on the Relevant Strategic Noise Mapping and Noise Action Plan

Implementation of Noise Barriers in Attiki Odos Motorway based on the relevant Strategic Noise Mapping and Noise Action Plan Konstantinos Vogiatzis Associate Professor, Laboratory of Transportation Environmental Acoustics (L.T.E.A.), Faculty of the Civil Engineering, University of Thessaly, Volos, Greece Vassiliki Zafiropoulou Dr. Researcher Laboratory of Transportation Environmental Acoustics (L.T.E.A.), Faculty of the Civil Engineering, University of Thessaly, Volos, Greece Summary Attiki Odos Motorway (the “Athens ring road”) constitutes one of the most important co-financed road projects in Europe, laying the foundations for the execution of a series of successful road concession projects in Greece. As per the Environmental Noise Protection and Monitoring, Attiki Odos has already implemented in 2009-2010 a Strategic Noise Map (SNM) and Noise Action Plan, followed by a full update in 2014 according to the directive 2002/49/EC (END). The updated Noise Action Plan (NAP), foreseen as main actions against road traffic noise, the implementation of reflective transparent noise barriers, partial motorway covers and also urban design tools. In order to validate the results, a comparison of the calculated noise indices Lden & Lnight results with the measured noise levels in more than 150 locations along the motorway - from the annual environmental noise monitoring program - was implemented proving exceptional correlation. According to the most recent results of the noise monitoring program of Attiki Odos during 2017, in the Geographical Section A13 (from K.P.32+600 to K.P.32+980 in both directions), a significant exceedance of levels of the above noise indicators, was documented as well as important residents’ complaints. -

The University of Chicago How to Move a God: Shifting

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO HOW TO MOVE A GOD: SHIFTING RELIGION AND IMPERIAL IDENTITIES IN ROMAN ATHENS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY JOSHUA RAMON VERA CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2018 Copyright © 2018 Joshua Ramon Vera All rights reserved. For Katharyn, άγκυρα µου Contents List of Illustrations vi Acknowledgements vii Abstract xi Introduction: Shifting Landscapes, Shifting Identities 1 Between Tradition and Transition 12 Religious Buildings or Building Religions? 22 Peeling back the Palimpsest 27 Chapter I: A Reputation for Piety 32 The Most God-fearing, as They Say: Classical Athenian Piety 33 The Possession of the Gods: The City as a Sacred Landscape 37 Shrines Made by Human Hands: The Early Christian View 41 Greater than Others in Piety: The Second-Century Perspective 47 The Glory of Your Ancestors: Imagining a Landscape 51 Equal or Opposite Reactions? 56 Whose Landscape Is It Anyway? 65 Chapter II: Memorials to Ancient Virtue 72 Imaging Athens 73 The Emergence of a Core 79 The Classical Image 84 The Heart of the City 95 The Hellenistic Image 103 The Roman Image 107 The Emergence of a Double Core 113 The Hadrianic Image 118 The Mark of the City 123 iv Chapter III: By the People, For the People? 132 Reduced, Reused, or Upcycled? 134 The Road to Recovery 137 Old Money, New Men 140 Roman Plans, Roman Hands? 145 Let Slide the Gods of War 149 A Tale of Two Staircases 161 A Tale of Two Streets 166 Office Space 180 By the -

Αthens and Attica in Prehistory Proceedings of the International Conference Athens, 27-31 May 2015

Αthens and Attica in Prehistory Proceedings of the International Conference Athens, 27-31 May 2015 edited by Nikolas Papadimitriou James C. Wright Sylvian Fachard Naya Polychronakou-Sgouritsa Eleni Andrikou Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-671-4 ISBN 978-1-78969-672-1 (ePdf) © 2020 Archaeopress Publishing, Oxford, UK Language editing: Anastasia Lampropoulou Layout: Nasi Anagnostopoulou/Grafi & Chroma Cover: Bend, Nasi Anagnostopoulou/Grafi & Chroma (layout) Maps I-IV, GIS and Layout: Sylvian Fachard & Evan Levine (with the collaboration of Elli Konstantina Portelanou, Ephorate of Antiquities of East Attica) Cover image: Detail of a relief ivory plaque from the large Mycenaean chamber tomb of Spata. National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Department of Collection of Prehistoric, Egyptian, Cypriot and Near Eastern Antiquities, no. Π 2046. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports, Archaeological Receipts Fund All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Printed in the Netherlands by Printforce This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Publication Sponsors Institute for Aegean Prehistory The American School of Classical Studies at Athens The J.F. Costopoulos Foundation Conference Organized by The American School of Classical Studies at Athens National and Kapodistrian University of Athens - Department of Archaeology and History of Art Museum of Cycladic Art – N.P. Goulandris Foundation Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports - Ephorate of Antiquities of East Attica Conference venues National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (opening ceremony) Cotsen Hall, American School of Classical Studies at Athens (presentations) Museum of Cycladic Art (poster session) Organizing Committee* Professor James C. -

The Christianization of the Peloponnese

THE CHRISTIANIZATION OF THE Antique churches in the Peloponnese PELOPONNESE: THE CASE FOR STRATEGIC undertaken in 2012, allows a synthetic CHANGE interpretation of all the material within the surrounding landscape to be possible.i While ABSTRACT the precise chronologies may remain elusive, The issue of the persistence of paganism is this present study shows how sociological now quite well considered; however, it is only theories of conversion processes can be in recent times that the same concern, applied to the topographic analysis of the late approached from another perspective, the antique churches of the Peloponnese to help multifaceted nature of the Christianization of determine the nature of Christianization the Peloponnese, has become the topic of across the diachronic range. In this work I will detailed discussion. It is likely that present some new theories regarding Christianization in Achaia took place processes and phases of conversion, and the incrementally and with a variety of effects implications of these in terms of according to the location (Sweetman 2010). understanding networks and society in the The processes of how this took place and Late Antique Peloponnese. under what circumstances remain to be discussed in detail. As a considered and active INTRODUCTIONii process, understanding methods of Epigraphic evidence indicates a steady growth conversion should provide insights into the οf a Christian presence in the Peloponnese nature of society at the time, particularly in throughout the 4th century (Foschia 2009, terms of communications. Church location 209-33), but the monumentalization of reflects a range of choices made in terms of Christianity here is comparatively late. -

The Ionic Friezes of the Hephaisteion in the Athenian Agora

The Ionic Friezes of the Hephaisteion in the Athenian Agora Katerina Velentza King’s College London Classical Archaeology Class of 2015 Abstract: This paper examines in depth all the features of the Ionic friezes of the Hephaisteion, their architectural position, their visibility, their iconography, their audience, their function and the intention of their construction. In contrast to the existing scholarship that examines separately single aspects of these architectural sculptures, in this research I have tried to investigate the Hephaisteion Ionic friezes as a whole and incorporate them in the ensemble of the other preserved Ionic friezes of fifth-century BC Attic Doric temples. My research started during the summer 2014 when I was working in the excavations of the Athenian Agora conducted by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. During this time I had the opportunity to familiarise myself in detail with the topography, the monuments of the site of the Agora and the excavation reports of the American School and carry out an autopsy in the Hephaisteion. Additionally, I was granted permission from the First Ephorate of Classical Antiquities, to enter the interior of the Parthenon in order to investigate in detail the architectural position and the visibility of the copies of the Ionic frieze still standing at the Western side of the temple. I also visited the temple of Poseidon at Sounion and the Archaeological Museum of Lavrion to examine the Ionic frieze surviving from this temple. Through the autopsy of these three temples and their Ionic friezes and after the detailed study of modern scholarship, I tried to understand and interpret the function and the purpose of the Ionic friezes within Athenian Doric temples as well as their broader cultural and historical context. -

Notes on Three Athenian Cult Places

NOTES ON THREE ATHENIAN CULT PLACES The· name of the late Professor Ant. D. Kbramopouwos is closely linked to the study of early Athens. The follow ing article is dedicated to his memory. PYTHION AND OLYMPION A crucial problem in the topography of early Athens has to do with the two primitive sanctuaries of Pythian Apollo and Olympian Zeus, which Thucydides (II 15) cites as proof of the location and extent of the early city. Near these two cult places was an altar of Zeus Astrapaios from which, as Strabo informs us1, the Py- thaistai watched for the lightning to flash over Harma, before they set out for their sacred mission to Delphi. Were these the shrines located on the North Slope of the Acropolis, a little above the Klepsydra (Fig. l), or are they the sanctuaries of the same name, in the southeastern section of the ancient city2 ? The arguments for the former view were set forth by A. D. KeramopoulloS in I92913, 2so convincingly that some scholars regard the problem as definitely settled 4 . * It is not necessary to discuss here all the factors that have a bearing on the question, since this has been done many times in the past, and especially in the art icle by KeramopoulloS. But there are still scholars who hold to the view that there was no cult of Zeus on the North Slope of the Acropolis and that the Pythion par excel lence was that near the Temple of Zeus southeast of the Acropolis. In an article pub lished in 1959 R.