The Ionic Friezes of the Hephaisteion in the Athenian Agora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

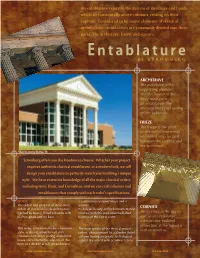

Entablature Refers to the System of Moldings and Bands Which Lie Horizontally Above Columns, Resting on Their Capitals

An entablature refers to the system of moldings and bands which lie horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Considered to be major elements of classical architecture, entablatures are commonly divided into three parts: the architrave, frieze, and cornice. E ntablature by stromberg ARCHITRAVE The architrave is the supporting element, and the lowest of the three main parts of an entablature: the undecorated lintel resting on the columns. FRIEZE The frieze is the plain or decorated horizontal unmolded strip located between the cornice and the architrave. Clay Academy, Dallas, TX Stromberg offers you the freedom to choose. Whether your project requires authentic classical entablature, or a modern look, we will design your entablature to perfectly match your building’s unique style . We have extensive knowledge of all the major classical orders, including Ionic, Doric, and Corinthian, and we can craft columns and entablatures that comply with each order’s specifications. DORIC a continuous sculpted frieze and a The oldest and simplest of these three cornice. CORNICE orders of classical Greek architecture, Its delicate beauty and rich ornamentation typified by heavy, fluted columns with contrast with the stark unembellished The cornice is the upper plain capitals and no base. features of the Doric order. part of an entablature; a decorative molded IONIC CORINTHIAN projection at the top of a This order, considered to be a feminine The most ornate of the three classical wall or window. style, is distinguished by tall slim orders, characterized by a slender fluted columns with flutes resting on molded column having an ornate, bell-shaped bases and crowned by capitals in the capital decorated with acanthus leaves. -

Edukacja Olimpijska Dla Gimnazjum

Michał Bronikowski Małgorzata Bronikowska Edukacja olimpijska dla gimnazjum Poradnik dla nauczycieli materiały i podręczniki Mariana Pietraszewskiego Poznań 2009 Redaktor Anna Kaczmarek Akwarele Wojciech Zabłocki, ze zbioru Muzeum Sportu i Turystyki (MSiT) w Warszawie (s. 11, 17, 18, 20, 23, 27, 31) Zdjęcia: GeoM – Fotolia.com (s. 15), arfo – Fotolia.com (s. 26), Katarzyna Rainka (s. 44), Leszek Fidusie- wicz (s. 47, 68, 69), Szymon Sikora (s. 38, 39, okładka – www.szymonsikora.com), Muzeum Sportu i Turystyki (MSiT) w Warszawie (s. 14, 32, 50), Małgorzata Bronikowska (s. 53, 69), Maurizio Ascione – Fotolia.com (s. 27), Wikipedia (s. 47, 66), Corel Corporation (s. 62), s. 76 od lewej: Stefan Baum – Fotolia.com, Małgorzata Bronikowska, Freefl y – Fotolia.com, Związek Piłki Ręcznej w Polsce, waveworld – Fotolia.com, Jorge Casais – Fotolia.com, Corel Corporation, Sportlibrary – Fotolia.com, Margo Harrison – Fotolia.com, Piotr Sikora – Fotolia.com, Piotr Sikora – Foto- lia.com, Nicholas Piccillo – Fotolia.com, Clarence Alford – Fotolia.com, Friday – Fotolia.com, Galina Barskaya – Fotolia.com, Yury Maryunin – Fotolia.com, Franc Podgoršek – Fotolia.com Konsultacja ikonografi czna Krzysztof Tomczak Łamanie komputerowe Reginaldo Cammarano Autorzy składają wyrazy podziękowania Panu dr. Marcinowi Czechowskiemu i Panu dr. Filipowi Kobieli za cenne uwagi, Panu Wojciechowi Zabłockiemu oraz Muzeum Sportu i Turystyki w Warszawie za udo- stępnienie prac plastycznych – akwarel dla celów edukacyjnych, Polskiemu Komitetowi Olimpijskiemu za możliwość wykorzystania zdjęć ze zbiorów Leszka Fidusiewicza, Katarzyny Rainki, Szymona Sikory. © Copyright by Polski Komitet Olimpijski, Warszawa 2009 ISBN ---- Ofi cyna Edukacyjna Wydawnictwa eMPi2 s.c. ul. św. Wojciech 28, 61-749 Poznań tel. 61 851 76 61, fax 61 853 06 76 www.empi2.pl, e-mail: [email protected] Spis treści Podstawa programowa ........................................................................................ -

Gallery Text That Accompanies This Exhibition In

Steeped in the classical training of an English gentleman, Edward Dodwell (1777/78– 1832) first traveled through Greece in 1801. He returned in 1805 in the company of an Italian artist, Simone Pomardi (1757–1830), and together they toured the country for fourteen months, drawing and documenting the landscape with exacting detail. They produced around a thousand illustrations, most of which are now in the collection of the Packard Humanities Institute in Los Altos, California. A selection from this rich archive is presented here for the first time in the United States. Dodwell and Pomardi frequently used a camera obscura, an optical device that made it easier to create accurate images. Beyond providing evidence for the appearance of monuments and vistas, their illustrations manifest the ideal of the picturesque that enraptured so many European travelers. The sight of ancient temples lying in ruin, or of the Greek people under Turkish rule as part of the Ottoman Empire, prompted meditation on the transience of human accomplishments. As Dodwell himself wrote: “When we contemplated the scene around us, and beheld the sites of ruined states, and kingdoms, and cities, which were once elevated to a high pitch of prosperity and renown, but which have now vanished like a dream . we could not but forcibly feel that nations perish as well as individuals.” Dodwell’s own words accompany the majority of images in this exhibition. His descriptions are drawn from his Classical and Topographical Tour through Greece, during the Years 1801, 1805, and 1806 (London, 1819). The author’s original spelling, capitalization, and punctuation have been retained. -

Athenians and Eleusinians in the West Pediment of the Parthenon

ATHENIANS AND ELEUSINIANS IN THE WEST PEDIMENT OF THE PARTHENON (PLATE 95) T HE IDENTIFICATION of the figuresin the west pedimentof the Parthenonhas long been problematic.I The evidencereadily enables us to reconstructthe composition of the pedimentand to identify its central figures.The subsidiaryfigures, however, are rath- er more difficult to interpret. I propose that those on the left side of the pediment may be identifiedas membersof the Athenian royal family, associatedwith the goddessAthena, and those on the right as membersof the Eleusinian royal family, associatedwith the god Posei- don. This alignment reflects the strife of the two gods on a heroic level, by referringto the legendary war between Athens and Eleusis. The recognition of the disjunctionbetween Athenians and Eleusinians and of parallelism and contrastbetween individualsand groups of figures on the pedimentpermits the identificationof each figure. The referenceto Eleusis in the pediment,moreover, indicates the importanceof that city and its majorcult, the Eleu- sinian Mysteries, to the Athenians. The referencereflects the developmentand exploitation of Athenian control of the Mysteries during the Archaic and Classical periods. This new proposalfor the identificationof the subsidiaryfigures of the west pedimentthus has critical I This article has its origins in a paper I wrote in a graduateseminar directedby ProfessorJohn Pollini at The Johns Hopkins University in 1979. I returned to this paper to revise and expand its ideas during 1986/1987, when I held the Jacob Hirsch Fellowship at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. In the summer of 1988, I was given a grant by the Committeeon Research of Tulane University to conduct furtherresearch for the article. -

Herakles Iconography on Tyrrhenian Amphorae

HERAKLES ICONOGRAPHY ON TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE _____________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia _____________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ______________________________________________ by MEGAN LYNNE THOMSEN Dr. Susan Langdon, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Susan Langdon, and the other members of my committee, Dr. Marcus Rautman and Dr. David Schenker, for their help during this process. Also, thanks must be given to my family and friends who were a constant support and listening ear this past year. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS……………………………………………………………..v Chapter 1. TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE—A BRIEF STUDY…..……………………....1 Early Studies Characteristics of Decoration on Tyrrhenian Amphorae Attribution Studies: Identifying Painters and Workshops Market Considerations Recent Scholarship The Present Study 2. HERAKLES ON TYRRHENIAN AMPHORAE………………………….…30 Herakles in Vase-Painting Herakles and the Amazons Herakles, Nessos and Deianeira Other Myths of Herakles Etruscan Imitators and Contemporary Vase-Painting 3. HERAKLES AND THE FUNERARY CONTEXT………………………..…48 Herakles in Etruria Etruscan Concepts of Death and the Underworld Etruscan Funerary Banquets and Games 4. CONCLUSION………………………………………………………………..67 iii APPENDIX: Herakles Myths on Tyrrhenian Amphorae……………………………...…72 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………..77 ILLUSTRATIONS………………………………………………………………………82 iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Tyrrhenian Amphora by Guglielmi Painter. Bloomington, IUAM 73.6. Herakles fights Nessos (Side A), Four youths on horseback (Side B). Photos taken by Megan Thomsen 82 2. Tyrrhenian Amphora (Beazley #310039) by Fallow Deer Painter. Munich, Antikensammlungen 1428. Photo CVA, MUNICH, MUSEUM ANTIKER KLEINKUNST 7, PL. 322.3 83 3. Tyrrhenian Amphora (Beazley #310045) by Timiades Painter (name vase). -

The Athenian Agora

Excavations of the Athenian Agora Picture Book No. 12 Prepared by Dorothy Burr Thompson Produced by The Stinehour Press, Lunenburg, Vermont American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1993 ISBN 87661-635-x EXCAVATIONS OF THE ATHENIAN AGORA PICTURE BOOKS I. Pots and Pans of Classical Athens (1959) 2. The Stoa ofAttalos II in Athens (revised 1992) 3. Miniature Sculpturefrom the Athenian Agora (1959) 4. The Athenian Citizen (revised 1987) 5. Ancient Portraitsfrom the Athenian Agora (1963) 6. Amphoras and the Ancient Wine Trade (revised 1979) 7. The Middle Ages in the Athenian Agora (1961) 8. Garden Lore of Ancient Athens (1963) 9. Lampsfrom the Athenian Agora (1964) 10. Inscriptionsfrom the Athenian Agora (1966) I I. Waterworks in the Athenian Agora (1968) 12. An Ancient Shopping Center: The Athenian Agora (revised 1993) I 3. Early Burialsfrom the Agora Cemeteries (I 973) 14. Graffiti in the Athenian Agora (revised 1988) I 5. Greek and Roman Coins in the Athenian Agora (1975) 16. The Athenian Agora: A Short Guide (revised 1986) French, German, and Greek editions 17. Socrates in the Agora (1978) 18. Mediaeval and Modern Coins in the Athenian Agora (1978) 19. Gods and Heroes in the Athenian Agora (1980) 20. Bronzeworkers in the Athenian Agora (1982) 21. Ancient Athenian Building Methods (1984) 22. Birds ofthe Athenian Agora (1985) These booklets are obtainable from the American School of Classical Studies at Athens c/o Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, N.J. 08540, U.S.A They are also available in the Agora Museum, Stoa of Attalos, Athens Cover: Slaves carrying a Spitted Cake from Market. -

The Gibbs Range of Classical Porches • the Gibbs Range of Classical Porches •

THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Andrew Smith – Senior Buyer C G Fry & Son Ltd. HADDONSTONE is a well-known reputable company and C G Fry & Son, award- winning house builder, has used their cast stone architectural detailing at a number of our South West developments over the last ten years. We erected the GIBBS Classical Porch at Tregunnel Hill in Newquay and use HADDONSTONE because of the consistency, product, price and service. Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, USA As an advocate of architectural literacy, it is gratifying to have Haddonstone’s informative brochure defining the basic components of literate classical porches. Hugh Petter’s cogent illustrations and analysis of the porches’ proportional systems make a complex subject easily grasped. A porch celebrates an entrance; it should be well mannered. James Gibbs’s versions of the classical orders are the appropriate choice. They are subtlety beautiful, quintessentially English, and fitting for America. Jeremy Musson, English author, editor and presenter Haddonstone’s new Gibbs range is the result of an imaginative collaboration with architect Hugh Petter and draws on the elegant models provided by James Gibbs, one of the most enterprising design heroes of the Georgian age. The result is a series of Doric and Ionic porches with a subtle variety of treatments which can be carefully adapted to bring elegance and dignity to houses old and new. www.haddonstone.com www.adamarchitecture.com 2 • THE GIBBS RANGE OF CLASSICAL PORCHES • Introduction The GIBBS Range of Classical Porches is designed The GIBBS Range is conceived around the two by Hugh Petter, Director of ADAM Architecture oldest and most widely used Orders - the Doric and and inspired by the Georgian architect James Ionic. -

MYTHOLOGY MAY 2018 Detail of Copy After Arpino's Perseus and Andromeda

HOMESCHOOL THIRD THURSDAYS MYTHOLOGY MAY 2018 Detail of Copy after Arpino's Perseus and Andromeda Workshop of Giuseppe Cesari (Italian), 1602-03. Oil on canvas. Bequest of John Ringling, 1936. Creature Creation Today, we challenge you to create your own mythological creature out of Crayola’s Model Magic! Open your packet of Model Magic and begin creating. If you need inspiration, take a look at the back of this sheet. MYTHOLOGICAL Try to incorporate basic features of animals – eyes, mouths, legs, etc.- while also combining part of CREATURES different creatures. Some works of art that we are featuring for Once you’ve finished sculpting, today’s Homeschool Third Thursday include come up with a unique name for creatures like the sea monster. Many of these your creature. Does your creature mythological creatures consist of various human have any special powers or and animal parts combined into a single creature- abilities? for example, a centaur has the body of a horse and the torso of a man. Other times the creatures come entirely from the imagination, like the sea monster shown above. Some of these creatures also have supernatural powers, some good and some evil. Mythological Creatures: Continued Greco-Roman mythology features many types of mythological creatures. Here are some ideas to get your project started! Sphinxes are wise, riddle- loving creatures with bodies of lions and heads of women. Greek hero Perseus rides a flying horse named Pegasus. Sphinx Centaurs are Greco- Pegasus Roman mythological creatures with torsos of men and legs of horses. Satyrs are creatures with the torsos of men and the legs of goats. -

The Acropolis

November 2010 The Acropolis Acropolis is actually a generic Greek term referring to citadel on high ground originally designed for defense, and a number of Ancient Greek cities could boast such, such as Argos, Thebes, and Corinth. It was Athen’s acropolis, though that has become the Acropolis to the modern world. The Acropolis was formally proclaimed as the pre-eminent monument on the European Cultural Heritage list of monuments in 2007. The Acropolis is a flat-topped rock which rises 490 ft above sea level in the city of Athens, with a surface area of about 3 hectares. By the time of Pericles, during the Golden Age of Athens (460–430 BC), a number of temples had already been build and destroyed on the Acropolis, but most of the major temples were rebuilt under Pericles, Phidias (a great Athenian sculptor) and Ictinus and Callicrates (two famous architects) . During the 5th century BC, the Acropolis gained its final shape. After winning at Eurymedon in 468 BC, Cimon and Themistocles ordered the reconstruction of southern and northern walls, and Pericles entrusted the building of the Parthenon to Ictinus and Phidias. The Parthenon is the dominant building one sees standing atop the Acropolis today. It has been judged by architects as the most perfect building ever built by Man, and it undoubtedly is one of the major reasons why the Acropolis is so famous. The entrance to the Acropolis was a monumental gateway called the Propylaea. To the south is the tiny Temple of Athena Nike. A bronze statue of Athena, by Phidias, originally stood at its centre. -

21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION Tel.: 2103202049, Fax: 2103226371

LIST OF BANK BRANCHES (BY HEBIC) 30/06/2015 BANK OF GREECE HEBIC BRANCH NAME AREA ADDRESS TELEPHONE NUMBER / FAX 0100001 HEAD OFFICE SECRETARIAT ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202049, fax: 2103226371 0100002 HEAD OFFICE TENDER AND ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS PROCUREMENT SECTION tel.: 2103203473, fax: 2103231691 0100003 HEAD OFFICE HUMAN ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS RESOURCES SECTION tel.: 2103202090, fax: 2103203961 0100004 HEAD OFFICE DOCUMENT ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202198, fax: 2103236954 0100005 HEAD OFFICE PAYROLL ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202096, fax: 2103236930 0100007 HEAD OFFICE SECURITY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202101, fax: 210 3204059 0100008 HEAD OFFICE SYSTEMIC CREDIT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS INSTITUTIONS SUPERVISION SECTION A tel.: 2103205154, fax: …… 0100009 HEAD OFFICE BOOK ENTRY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECURITIES MANAGEMENT SECTION tel.: 2103202620, fax: 2103235747 0100010 HEAD OFFICE ARCHIVES ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS SECTION tel.: 2103202206, fax: 2103203950 0100012 HEAD OFFICE RESERVES ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS MANAGEMENT BACK UP SECTION tel.: 2103203766, fax: 2103220140 0100013 HEAD OFFICE FOREIGN ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. Venizelou Ave., 102 50 ATHENS EXCHANGE TRANSACTIONS SECTION tel.: 2103202895, fax: 2103236746 0100014 HEAD OFFICE SYSTEMIC CREDIT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS INSTITUTIONS SUPERVISION SECTION B tel.: 2103205041, fax: …… 0100015 HEAD OFFICE PAYMENT ATHENS CENTRE 3, Amerikis, 102 50 ATHENS SYSTEMS OVERSIGHT SECTION tel.: 2103205073, fax: …… 0100016 HEAD OFFICE ESCB PROJECTS CHALANDRI 341, Mesogeion Ave., 152 31 CHALANDRI AUDIT SECTION tel.: 2106799743, fax: 2106799713 0100017 HEAD OFFICE DOCUMENTARY ATHENS CENTRE 21, El. -

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract. -

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter.