The Causes and Consequences of an Unprecedented Political Rise Birgit Holzer1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

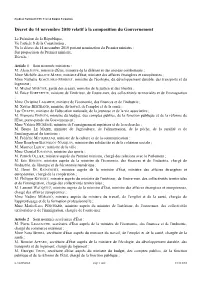

Décret Du 14 Novembre 2010 Relatif À La Composition Du Gouvernement

Syndicat National CFTC Travail Emploi Formation Décret du 14 novembre 2010 relatif à la composition du Gouvernement Le Président de la République, Vu l'article 8 de la Constitution ; Vu le décret du 14 novembre 2010 portant nomination du Premier ministre ; Sur proposition du Premier ministre, Décrète : Article 1 Sont nommés ministres : M. Alain JUPPÉ , ministre d'État, ministre de la défense et des anciens combattants ; Mme Michèle ALLIOT -MARIE , ministre d'État, ministre des affaires étrangères et européennes ; Mme Nathalie KOSCIUSKO -MORIZET , ministre de l'écologie, du développement durable, des transports et du logement ; M. Michel MERCIER , garde des sceaux, ministre de la justice et des libertés ; M. Brice HORTEFEUX , ministre de l'intérieur, de l'outre-mer, des collectivités territoriales et de l'immigration ; Mme Christine LAGARDE , ministre de l'économie, des finances et de l'industrie ; M. Xavier BERTRAND , ministre du travail, de l'emploi et de la santé ; Luc CHATEL , ministre de l'éducation nationale, de la jeunesse et de la vie associative ; M. François BAROIN , ministre du budget, des comptes publics, de la fonction publique et de la réforme de l'État, porte-parole du Gouvernement ; Mme Valérie PÉCRESSE , ministre de l'enseignement supérieur et de la recherche ; M. Bruno LE MAIRE , ministre de l'agriculture, de l'alimentation, de la pêche, de la ruralité et de l'aménagement du territoire ; M. Frédéric MITTERRAND , ministre de la culture et de la communication ; Mme Roselyne BACHELOT -NARQUIN , ministre des solidarités et de la cohésion sociale ; M. Maurice LEROY , ministre de la ville ; Mme Chantal JOUANNO , ministre des sports ; M. -

Une Brève Histoire De L'avenir

Master en Sciences de Gestion, mention Management, Spécialité Prospective, Stratégie et Organisation. 2006-2007 FICHE DE LECTURE Une brève histoire de l’avenir Auteur : J. ATTALI Gonzague MARTIN Une brève histoire de l'avenir Une brève histoire de l'avenir..................................................................................................... 1 1. Biographie .............................................................................................................................. 3 2. Les hypothèses ....................................................................................................................... 5 3. Postulats ................................................................................................................................. 6 4. Résumé................................................................................................................................... 8 5. Critiques ............................................................................................................................... 19 6. Discussion ............................................................................................................................ 28 7. Conclusions .......................................................................................................................... 34 8. Bibliographie........................................................................................................................ 36 2 1. Biographie En 1943 le 1er novembre , il naît avec son frère -

European Movement International 04/12/2020, 09:17

European Movement International 04/12/2020, 09:17 Valéry Giscard d'Estaing: Mourning a European giant Following the passing of former French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, former president of the European Movement International and passionate defender of the European project, we share perspectives on his life from France, Belgium, Germany and Malta. European Headlines is a weekly newsletter from the European Movement International highlighting media perspectives from across Europe. Click here to subscribe. Tweet about this Remembering VGE Le Monde provides a brief biography of the former French president, who passed away on Wednesday as a result of a Covid-19 infection. At the age of 36, Giscard was appointed Minister of Finance and Economic Affairs under Georges Pompidou. In 1974, he ran in the 1974 presidential elections, defeating Jacques Chaban-Delmas and François Mitterrand and thus becoming the youngest President of the Republic since 1848. During the campaign, he established himself as a modern, dynamic politician, embodying renewal in the face of his rivals. His “advanced liberal society” entailed new laws such as the decriminalisation of abortion and the right of referral to the Constitutional Council. His international policies are marked by his strengthening of European unity. Together with German Chancellor, Helmut Schmidt, Giscard influenced the creation of the European Council in December 1974. Following the 1989 European elections, Giscard entered the European Parliament. During his years in Brussels, he served as President of the European Movement International until 1997. On May 29, 2003, he received the ‘Charlemagne Prize’ for having "advanced the unification process" in Europe. Read the full article Modern man L’Echo reports on what the former President has meant for Europe. -

The Sarkozy Effect France’S New Presidential Dynamic J.G

Politics & Diplomacy The Sarkozy Effect France’s New Presidential Dynamic J.G. Shields Nicolas Sarkozy’s presidential campaign was predicated on the J.G. Shields is an associate professor of need for change in France, for a break—“une rupture”—with the French Studies at the past. His election as president of the French Republic on 6 University of Warwick in England. He is the first May 2007 ushered in the promise of a new era. Sarkozy’s pres- holder of the American idency follows those of the Socialist François Mitterrand Political Science Associ- ation's Stanley Hoff- (1981-95) and the neo-Gaullist Jacques Chirac (1995-2007), mann Award (2007) for who together occupied France’s highest political office for his writing on French more than a quarter-century. Whereas Mitterrand and Chirac politics. bowed out in their seventies, Sarkozy comes to office aged only fifty-two. For the first time, the French Fifth Republic has a president born after the Second World War, as well as a presi- dent of direct immigrant descent.1 Sarkozy’s emphatic victory, with 53 percent of the run-off vote against the Socialist Ségolène Royal, gave him a clear mandate for reform. The near-record turnout of 84 percent for both rounds of the election reflected the public demand for change. The legislative elections of June 2007, which assured a strong majority in the National Assembly for Sarkozy’s centre-right Union pour un Mouvement Populaire (UMP), cleared the way for implementing his agenda over the next five years.2 This article examines the political context within which Sarkozy was elected to power, the main proposals of his presidential program, the challenges before him, and his prospects for bringing real change to a France that is all too evidently in need of reform. -

Why Emmanuel Macron Is the Most Gaullist of All Candidates for the French Presidential Elections of 2017

Policy Paper Centre international Note de recherche de formation européenne Matthias Waechter*, April 18th , 2017* CIFE Policy Paper N°53 Nothing new in French politics? Why Emmanuel Macron is the most Gaullist of all candidates for the French presidential elections of 2017 The French presidential campaign of 2017 turns soon as he exercised power from 1958 onwards, his very much around the buzzword of renewal: assertion lost its credibility and he was quickly Renewal of the political elites, the morals and perceived as the overarching figure of the French habits of political leaders, the party system. Some Right, triggering by the same token the consolida- of the candidates, most prominently far-left politi- tion of a leftist opposition. cian Jean-Luc Mélenchon, even fight for a constitu- tional turnover and the creation of a "Sixth Repu- The claim to pave a third way between left and blic". Among the five leading candidates, one right, to transcend the allegedly unproductive presents himself not only as an innovator, but also conflict between those political currents is at the as a revolutionary: It is Emmanuel Macron with his core of Emmanuel Macron's political stance. He movement "En Marche!" The campaign book by the doesn't deny his origins from the political left, but former minister of the economy appeared under the asserts that this cleavage is nowadays obsolete title "Revolution" and traces the way towards a and that good ideas should be taken from all profoundly changed France beyond the cleavage of camps. His movement "En Marche!" posts on its Left and Right. -

Murder in Aubagne: Lynching, Law, and Justice During the French

This page intentionally left blank Murder in Aubagne Lynching, Law, and Justice during the French Revolution This is a study of factions, lynching, murder, terror, and counterterror during the French Revolution. It examines factionalism in small towns like Aubagne near Marseille, and how this produced the murders and prison massacres of 1795–1798. Another major theme is the conver- gence of lynching from below with official terror from above. Although the Terror may have been designed to solve a national emergency in the spring of 1793, in southern France it permitted one faction to con- tinue a struggle against its enemies, a struggle that had begun earlier over local issues like taxation and governance. This study uses the tech- niques of microhistory to tell the story of the small town of Aubagne. It then extends the scope to places nearby like Marseille, Arles, and Aix-en-Provence. Along the way, it illuminates familiar topics like the activity of clubs and revolutionary tribunals and then explores largely unexamined areas like lynching, the sociology of factions, the emer- gence of theories of violent fraternal democracy, and the nature of the White Terror. D. M. G. Sutherland received his M.A. from the University of Sussex and his Ph.D. from the University of London. He is currently professor of history at the University of Maryland, College Park. He is the author of The Chouans: The Social Origins of Popular Counterrevolution in Upper Brittany, 1770–1796 (1982), France, 1789–1815: Revolution and Counterrevolution (1985), and The French Revolution, 1770– 1815: The Quest for a Civic Order (2003) as well as numerous scholarly articles. -

En Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, La Région Éreintée Par La Méthode Wauquiez

Directeur de la publication : Edwy Plenel www.mediapart.fr 1 percute vite », reconnaît François-Xavier Pénicaud, En Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, la région élu régional du MoDem, qui a pourtant quitté sa majorité en 2019. Isabelle Surply, du Rassemblement éreintée par la méthode Wauquiez national (RN), salue « l’animal politique », l’homme PAR ILYES RAMDANI ARTICLE PUBLIÉ LE MARDI 22 DÉCEMBRE 2020 « brillant » qui « cite Sophocle et Aristote » en assemblée plénière. À la tête de la deuxième région de France, Laurent Wauquiez cultive depuis cinq ans une pratique autoritaire, centralisée et verticale du pouvoir. Dans l’administration régionale, dans l’opposition et au sein même de sa majorité, son hyperprésidence a cristallisé les contestations. Laurent Wauquiez en avril 2020, à Lyon. © Nicolas Liponne / Hans Lucas via AFP Avec les fonctionnaires de la région, Laurent Wauquiez sait jouer la carte du bon père de famille. « Si vous le croisez devant un ascenseur, il vous demandera dans quel service vous bossez, si vous avez Laurent Wauquiez en avril 2020, à Lyon. © Nicolas Liponne / Hans Lucas via AFP un souci », raconte Christian Darpheuille, de l’Unsa. Lyon (Rhône). – Lorsqu’on l’interroge à ce Chez lui, en Haute-Loire, on évoque sa mémoire sujet, notre interlocuteur balaie rapidement du « incroyable », cette faculté à se souvenir du prénom regard le couloir qu’il nous fait traverser. Dans de gens rencontrés un an auparavant, « et même du les couloirs de l’hôtel de région, parler de prénom des enfants ». Laurent Wauquiez n’est pas chose aisée. « C’est Côté face, les mêmes interlocuteurs décrivent par l’omerta, personne n’ose rien dire », soupire Éric le menu la gouvernance verticale et autoritaire d’un Faussemagne, représentant syndical de la FSU. -

![Annales Historiques De La Révolution Française, 371 | Janvier-Mars 2013, « Robespierre » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Mars 2016, Consulté Le 01 Juillet 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1461/annales-historiques-de-la-r%C3%A9volution-fran%C3%A7aise-371-janvier-mars-2013-%C2%AB-robespierre-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-01-mars-2016-consult%C3%A9-le-01-juillet-2021-181461.webp)

Annales Historiques De La Révolution Française, 371 | Janvier-Mars 2013, « Robespierre » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 01 Mars 2016, Consulté Le 01 Juillet 2021

Annales historiques de la Révolution française 371 | janvier-mars 2013 Robespierre Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ahrf/12668 DOI : 10.4000/ahrf.12668 ISSN : 1952-403X Éditeur : Armand Colin, Société des études robespierristes Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 mars 2013 ISBN : 978-2-200-92824-7 ISSN : 0003-4436 Référence électronique Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 371 | janvier-mars 2013, « Robespierre » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 mars 2016, consulté le 01 juillet 2021. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ahrf/12668 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ahrf.12668 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 1 juillet 2021. Tous droits réservés 1 SOMMAIRE Introduction « Je vous laisse ma mémoire […] » Michel Biard Articles La souscription nationale pour sauvegarder les manuscrits de Robespierre : introspection historique d’une initiative citoyenne et militante Serge Aberdam et Cyril Triolaire Les manuscrits de Robespierre Annie Geffroy Les factums de l’avocat Robespierre. Les choix d’une défense par l’imprimé Hervé Leuwers Robespierre dans les publications françaises et anglophones depuis l’an 2000 Marc Belissa et Julien Louvrier Robespierre libéral Yannick Bosc Robespierre et la guerre, une question posée dès 1789 ? Thibaut Poirot « Mes forces et ma santé ne peuvent suffire ». crises politiques, crises médicales dans la vie de Maximilien Robespierre, 1790-1794 Peter McPhee Robespierre et l’authenticité révolutionnaire Marisa Linton Sources Maximilien de Robespierre, élève à Louis-le-Grand (1769-1781). Les apports de la comptabilité du « collège d’Arras » Hervé Leuwers Nouvelles pièces sur Robespierre et les colonies en 1791 Jean-Daniel Piquet Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 371 | janvier-mars 2013 2 Comptes rendus Lia van der HEIJDEN et Jan SANDERS (éds.), De Levensloop van Adriaan van der Willingen (1766-1841). -

Luxembourg Resistance to the German Occupation of the Second World War, 1940-1945

LUXEMBOURG RESISTANCE TO THE GERMAN OCCUPATION OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR, 1940-1945 by Maureen Hubbart A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Major Subject: History West Texas A&M University Canyon, TX December 2015 ABSTRACT The history of Luxembourg’s resistance against the German occupation of World War II has rarely been addressed in English-language scholarship. Perhaps because of the country’s small size, it is often overlooked in accounts of Western European History. However, Luxembourgers experienced the German occupation in a unique manner, in large part because the Germans considered Luxembourgers to be ethnically and culturally German. The Germans sought to completely Germanize and Nazify the Luxembourg population, giving Luxembourgers many opportunities to resist their oppressors. A study of French, German, and Luxembourgian sources about this topic reveals a people that resisted in active and passive, private and public ways. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Clark for her guidance in helping me write my thesis and for sharing my passion about the topic of underground resistance. My gratitude also goes to Dr. Brasington for all of his encouragement and his suggestions to improve my writing process. My thanks to the entire faculty in the History Department for their support and encouragement. This thesis is dedicated to my family: Pete and Linda Hubbart who played with and took care of my children for countless hours so that I could finish my degree; my husband who encouraged me and always had a joke ready to help me relax; and my parents and those members of my family living in Europe, whose history kindled my interest in the Luxembourgian resistance. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Remarks Prior to a Meeting

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Remarks Prior to a Meeting With President Emmanuel Macron of France and an Exchange With Reporters in Caen, France June 6, 2019 [President Macron began his remarks in French, and no translation was provided.] President Macron. I will say a few words in English, and I will repeat them exactly what I say. And I wanted first to thank you, President Donald Trump, for your presence here in this place. And thanks to your country, your nation, and your veterans. This morning we paid this tribute to their courage. And I think it was a great moment to celebrate and celebrate these people. President Trump. It was. President Macron. And I think your presence here to celebrate them, and their presence, is for me the best evidence of this unbreakable links between our two nations. From the very beginning of the American nation and all over the different centenaries, I think this message they conveyed to us, and our main tribute, is precisely to protect freedom and democracy everywhere. And this is why I'm always extremely happy to discuss with you in Washington, in Paris, or everywhere, in Caen today, is because we work very closely together. Our soldiers work very closely together—— President Trump. It's true, it's true. President Macron. ——in Sahel, in Iraq, in Syria. Each time freedom and democracy is at stake, we work closely together, and we will follow up. So thanks for this friendship. President Trump. Thank you very much. President Macron. Thanks for what your country did for my country. -

Language Planning and Textbooks in French Primary Education During the Third Republic

Rewriting the Nation: Language Planning and Textbooks in French Primary Education During the Third Republic By Celine L Maillard A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Douglas P Collins, Chair Maya A Smith Susan Gaylard Ana Fernandez Dobao Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of French and Italian Studies College of Arts and Sciences ©Copyright 2019 Céline L Maillard University of Washington Abstract Rewriting the Nation: Language Planning and Textbooks in French Primary Education During the Third Republic Celine L Maillard Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Douglas P Collins Department of French and Italian Studies This research investigates the rewriting of the nation in France during the Third Republic and the role played by primary schools in the process of identity formation. Le Tour de la France par deux enfants, a textbook written in 1877 by Augustine Fouillée, is our entry point to illustrate the strategies used in manufacturing French identity. We also analyze other texts: political speeches from the revolutionary era and from the Third Republic, as well as testimonies from both students and teachers written during the twentieth century. Bringing together close readings and research from various fields – history, linguistics, sociology, and philosophy – we use an interdisciplinary approach to shed light on language and national identity formation. Our findings underscore the connections between French primary education and national identity. Our analysis also contends that national identity in France during the Third Republic was an artificial construction and demonstrates how otherness was put in the service of populism. -

MEDIA POLARIZATION “À LA FRANÇAISE”? Comparing the French and American Ecosystems

institut montaigne MEDIA POLARIZATION “À LA FRANÇAISE”? Comparing the French and American Ecosystems REPORT MAY 2019 MEDIA POLARIZATION “À LA FRANÇAISE” MEDIA POLARIZATION There is no desire more natural than the desire for knowledge MEDIA POLARIZATION “À LA FRANÇAISE”? Comparing the French and American Ecosystems MAY 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In France, representative democracy is experiencing a growing mistrust that also affects the media. The latter are facing major simultaneous challenges: • a disruption of their business model in the digital age; • a dependence on social networks and search engines to gain visibility; • increased competition due to the convergence of content on digital media (competition between text, video and audio on the Internet); • increased competition due to the emergence of actors exercising their influence independently from the media (politicians, bloggers, comedians, etc.). In the United States, these developments have contributed to the polarization of the public square, characterized by the radicalization of the conservative press, with significant impact on electoral processes. Institut Montaigne investigated whether a similar phenomenon was at work in France. To this end, it led an in-depth study in partnership with the Sciences Po Médialab, the Sciences Po School of Journalism as well as the MIT Center for Civic Media. It also benefited from data collected and analyzed by the Pew Research Center*, in their report “News Media Attitudes in France”. Going beyond “fake news” 1 The changes affecting the media space are often reduced to the study of their most visible symp- toms. For instance, the concept of “fake news”, which has been amply commented on, falls short of encompassing the complexity of the transformations at work.