TIPA: a System for Processing Phonetic Symbols in LATEX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hebrew Alphabet

BBH2 Textbook Supplement Chapter 1 – The Hebrew Alphabet 1 The following comments explain, provide mnemonics for, answer questions that students have raised about, and otherwise supplement the second edition of Basics of Biblical Hebrew by Pratico and Van Pelt. Chapter 1 – The Hebrew Alphabet 1.1 The consonants For begadkephat letters (§1.5), the pronunciation in §1.1 is the pronunciation with the Dagesh Lene (§1.5), even though the Dagesh Lene is not shown in §1.1. .Kaf” has an “off” sound“ כ The name It looks like open mouth coughing or a cup of coffee on its side. .Qof” is pronounced with either an “oh” sound or an “oo” sound“ ק The name It has a circle (like the letter “o” inside it). Also, it is transliterated with the letter q, and it looks like a backwards q. here are different wa s of spellin the na es of letters. lef leph leˉ There are many different ways to write the consonants. See below (page 3) for a table of examples. See my chapter 1 overheads for suggested letter shapes, stroke order, and the keys to distinguishing similar-looking letters. ”.having its dot on the left: “Sin is never ri ht ׂש Mnemonic for Sin ׁש and Shin ׂש Order of Sin ׁש before Shin ׂש Our textbook and Biblical Hebrew lexicons put Sin Some alphabet songs on YouTube reverse the order of Sin and Shin. Modern Hebrew dictionaries, the acrostic poems in the Bible, and ancient abecedaries (inscriptions in which someone wrote the alphabet) all treat Sin and Shin as the same letter. -

The Origin of the Peculiarities of the Vietnamese Alphabet André-Georges Haudricourt

The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet André-Georges Haudricourt To cite this version: André-Georges Haudricourt. The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet. Mon-Khmer Studies, 2010, 39, pp.89-104. halshs-00918824v2 HAL Id: halshs-00918824 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00918824v2 Submitted on 17 Dec 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Published in Mon-Khmer Studies 39. 89–104 (2010). The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet by André-Georges Haudricourt Translated by Alexis Michaud, LACITO-CNRS, France Originally published as: L’origine des particularités de l’alphabet vietnamien, Dân Việt Nam 3:61-68, 1949. Translator’s foreword André-Georges Haudricourt’s contribution to Southeast Asian studies is internationally acknowledged, witness the Haudricourt Festschrift (Suriya, Thomas and Suwilai 1985). However, many of Haudricourt’s works are not yet available to the English-reading public. A volume of the most important papers by André-Georges Haudricourt, translated by an international team of specialists, is currently in preparation. Its aim is to share with the English- speaking academic community Haudricourt’s seminal publications, many of which address issues in Southeast Asian languages, linguistics and social anthropology. -

ENG ME 566 Advanced Engineering Mathematics Instructor: M

Fall 2011 ME 566 Advanced Engineering Mathematics ENG ME 566 Advanced Engineering Mathematics Instructor: M. S. Howe EMA 218 (730 Commonwealth Ave) [email protected] Prerequisites: Multivariate Calculus; Ordinary Differential Equations; or instructor permission. It is expected that you can already: • solve simple first and second order linear ordinary differential equations • differentiate and integrate elementary functions, including trigonometric, exponential and hyperbolic functions • integrate by parts; evaluate simple surface and volume integrals • use the binomial theorem and the series expansions of elementary functions (sine, cosine, exponential, logarithmic and hyperbolic functions) • do all the problems in the prerequisites self test at the end of these notes. Course Outcomes: • consolidate understanding of vector calculus and applications to graduate level engi- neering • introductory understanding of complex variable theory with applications to engineering problems • ability to solve standard partial differential equations of engineering science using eigen- function expansions, Fourier transforms and generalised functions • become proficient in documenting calculations Textbook: Lectures are based on Mathematical Methods for Mechanical Sciences (M. S. Howe; 6th edition). It can be downloaded in pdf form from the ME 566 BlackBoard web site. You are expected to ‘read around’ the subject, and are recommended to consult other textbooks such as those listed on page 5. Course grading: • 4 take-home examinations (12.5% each) • final closed book examination (50%) Fall 2011 1 ME 566 Advanced Engineering Mathematics Fall 2011 ME 566 Advanced Engineering Mathematics Homework: Four ungraded homework assignments provide practice in applying techniques taught in class – model answers will be posted on BlackBoard. In addition there are four take home exams each consisting of a short essay and 5 problems. -

Agreement Between the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan, The

AGREEMENT Between the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan, the Government of the Kyrgyz Republic and the Government of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Cooperation in the Area of Environment and Rational Nature Use The Governments of the participating countries of the Agreement hereinafter referred to as the Parties, Guided by the Treaty on Eternal Friendship between the Republic of Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic and the Republic of Uzbekistan, signed in Bishkek, January 10, 1997; Attaching great significance to environmental protection and rational use of the natural resources and desiring to obtain practical results in this field by means of effective cooperation; Realistically estimating potentialities of ecological dangers in the context of unfavorable natural climatic and hydrometeorological conditions, and acknowledging these problems as the common tasks; Recognizing the great importance of protection and improvement of the environmental situation, prudent and zealous use of natural resources for effectuation of economic and social development with due regard to the interests of the living and future generations; Expressing confidence that cooperation while solving common problems in the environmental protection in each of the countries meets their mutual advantage; and Desiring thereafter to promote the international efforts through this cooperation, aimed at protection and improvement of the environment and rational use of natural resources as the basis of the sound development on the global and regional levels; Have agreed as follows: Article I The Parties shall develop cooperation in the area of environmental protection and rational use of natural resources on the basis of equality of rights, mutual benefit pursuant to the Laws of the respective Countries. -

PARK JIN HYOK, Also Known As ("Aka") "Jin Hyok Park," Aka "Pak Jin Hek," Case Fl·J 18 - 1 4 79

AO 91 (Rev. 11/11) Criminal Complaint UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the RLED Central District of California CLERK U.S. DIS RICT United States ofAmerica JUN - 8 ?018 [ --- .. ~- ·~".... ~-~,..,. v. CENT\:y'\ l i\:,: ffl1G1 OF__ CAUFORN! BY .·-. ....-~- - ____D=E--..... PARK JIN HYOK, also known as ("aka") "Jin Hyok Park," aka "Pak Jin Hek," Case fl·J 18 - 1 4 79 Defendant. CRIMINAL COMPLAINT I, the complainant in this case, state that the following is true to the best ofmy knowledge and belief. Beginning no later than September 2, 2014 and continuing through at least August 3, 2017, in the county ofLos Angeles in the Central District of California, the defendant violated: Code Section Offense Description 18 U.S.C. § 371 Conspiracy 18 u.s.c. § 1349 Conspiracy to Commit Wire Fraud This criminal complaint is based on these facts: Please see attached affidavit. IBJ Continued on the attached sheet. Isl Complainant's signature Nathan P. Shields, Special Agent, FBI Printed name and title Sworn to before ~e and signed in my presence. Date: ROZELLA A OLIVER Judge's signature City and state: Los Angeles, California Hon. Rozella A. Oliver, U.S. Magistrate Judge Printed name and title -:"'~~ ,4G'L--- A-SA AUSAs: Stephanie S. Christensen, x3756; Anthony J. Lewis, x1786; & Anil J. Antony, x6579 REC: Detention Contents I. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................1 II. PURPOSE OF AFFIDAVIT ......................................................................1 III. SUMMARY................................................................................................3 -

Frequently Asked Questions Coins and Notes July 2020

Frequently Asked Questions Coins and Notes July 2020 A. Currency Issuance 1. Under what authority does the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) issue currency? The BSP is the sole government institution mandated by law to issue notes and coins for circulation in the Philippines. In Particular, Section 50 of Republic Act (R.A) No. 7653, otherwise known as The New Central Bank Act, as amended by Republic Act No. 11211, stipulates that the BSP shall have the sole power and authority to issue currency within the territory of the Philippines. It also issues legal tender commemorative notes and coins. 2. How does the BSP determine the volume/value of notes and coins to be issued annually? The annual volume/value of currency to be issue is projected based on currency demand that is estimated from a set of economic indicators which generally measure the country’s economic activity. Other variables considered in estimating currency order include: required currency reserves, unfit notes for replacement, and beginning inventory balance. The total amount of banknotes and coins that the BSP may issue should not exceed the total assets of the BSP. 3. How is currency issued to the public? Based on forecast of currency demand, denominational order of banknotes and coins is submitted to the Currency Production Sub-Sector (CPSS) for production of banknotes and coins. The CPSS delivers new BSP banknotes and coins to the Cash Department (CD) and the Regional Operations Sub-Sector (ROSS). In turn, CD services withdrawals of notes and coins of banks in the regions through its 22 Regional Offices/Branches. -

Ffontiau Cymraeg

This publication is available in other languages and formats on request. Mae'r cyhoeddiad hwn ar gael mewn ieithoedd a fformatau eraill ar gais. [email protected] www.caerphilly.gov.uk/equalities How to type Accented Characters This guidance document has been produced to provide practical help when typing letters or circulars, or when designing posters or flyers so that getting accents on various letters when typing is made easier. The guide should be used alongside the Council’s Guidance on Equalities in Designing and Printing. Please note this is for PCs only and will not work on Macs. Firstly, on your keyboard make sure the Num Lock is switched on, or the codes shown in this document won’t work (this button is found above the numeric keypad on the right of your keyboard). By pressing the ALT key (to the left of the space bar), holding it down and then entering a certain sequence of numbers on the numeric keypad, it's very easy to get almost any accented character you want. For example, to get the letter “ô”, press and hold the ALT key, type in the code 0 2 4 4, then release the ALT key. The number sequences shown from page 3 onwards work in most fonts in order to get an accent over “a, e, i, o, u”, the vowels in the English alphabet. In other languages, for example in French, the letter "c" can be accented and in Spanish, "n" can be accented too. Many other languages have accents on consonants as well as vowels. -

Combining Diacritical Marks Range: 0300–036F the Unicode Standard

Combining Diacritical Marks Range: 0300–036F The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0 This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0. Characters in this chart that are new for The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0 are shown in conjunction with any existing characters. For ease of reference, the new characters have been highlighted in the chart grid and in the names list. This file will not be updated with errata, or when additional characters are assigned to the Unicode Standard. See http://www.unicode.org/charts for access to a complete list of the latest character charts. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the on-line reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 4.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this excerpt file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0 (ISBN 0-321-18578-1), as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24 and #29, the other Unicode Technical Reports and the Unicode Character Database, which are available on-line. See http://www.unicode.org/Public/UNIDATA/UCD.html and http://www.unicode.org/unicode/reports A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. Fonts The shapes of the reference glyphs used in these code charts are not prescriptive. Considerable variation is to be expected in actual fonts. -

Pulley / Descender / Belay Device

Multi-Purpose Device 11 mm EN FR NO SE Model No. 333010-CE Pulley / Descender / Belay Device EN 12278:2007 EN 341:2011/2A 1019 EN 12841:2006/C Patented WARNING Activities involving the use of this device are potentially dangerous. You are responsible for your own actions and decisions. Before using this device, you must: • Read and understand these user instructions and • Familiarize yourself with its capabilities warnings; and limitations; • Get specific training in its proper use; • Understand and accept the risks involved. FAILURE TO HEED ANY OF THESE WARNINGS MAY RESULT IN SEVERE INJURY OR DEATH. 0 Traceability and Markings D E B F A G C 1019 A. Body controlling production of this PPE E. Individual........................... number No. 1019 00 000 M 0000 VVUÚ, a.s. Unit serial number Pikartská 1337/7 716 07 Ostrava - Radvanice Control Czech Republic Day of manufacture Year of manufacture B. Standards F. Anchor/load end of rope C. Carefully read the instructions for use G. Free end of rope D. Model identification 2 1 Field of Application 4 Inspection, Points to Verify See Text See Text 2 Breaking Strength 5 Compatibility 44 kN O 11 mm (EN) Rope (core + sheath) static, semi-static (EN 1891) type A 22 kN 22 kN 3 Nomenclature of Parts See Text 2 7 8 1 6 10 9 3 5 4 3 6 Installing the Rope LOAD SIDE 2 4 1 3 7 Function Test 8 Securing Function Test STOP! 4 9a EN 341:2011/2A Rescue Descender Lowering From Anchor— Maximum Descent Height: 200 m One Person Minimum/Maximum Working Load: 30–240 kg Maximum Descent Rate: 2 m/s Descent—Two People -

Gerard Manley Hopkins' Diacritics: a Corpus Based Study

Gerard Manley Hopkins’ Diacritics: A Corpus Based Study by Claire Moore-Cantwell This is my difficulty, what marks to use and when to use them: they are so much needed, and yet so objectionable.1 ~Hopkins 1. Introduction In a letter to his friend Robert Bridges, Hopkins once wrote: “... my apparent licences are counterbalanced, and more, by my strictness. In fact all English verse, except Milton’s, almost, offends me as ‘licentious’. Remember this.”2 The typical view held by modern critics can be seen in James Wimsatt’s 2006 volume, as he begins his discussion of sprung rhythm by saying, “For Hopkins the chief advantage of sprung rhythm lies in its bringing verse rhythms closer to natural speech rhythms than traditional verse systems usually allow.”3 In a later chapter, he also states that “[Hopkins’] stress indicators mark ‘actual stress’ which is both metrical and sense stress, part of linguistic meaning broadly understood to include feeling.” In his 1989 article, Sprung Rhythm, Kiparsky asks the question “Wherein lies [sprung rhythm’s] unique strictness?” In answer to this question, he proposes a system of syllable quantity coupled with a set of metrical rules by which, he claims, all of Hopkins’ verse is metrical, but other conceivable lines are not. This paper is an outgrowth of a larger project (Hayes & Moore-Cantwell in progress) in which Kiparsky’s claims are being analyzed in greater detail. In particular, we believe that Kiparsky’s system overgenerates, allowing too many different possible scansions for each line for it to be entirely falsifiable. The goal of the project is to tighten Kiparsky’s system by taking into account the gradience that can be found in metrical well-formedness, so that while many different scansion of a line may be 1 Letter to Bridges dated 1 April 1885. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

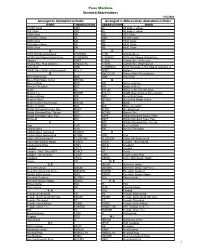

Arranged in Abbreviation Alphabetical Order Arranged in Alphabetical Order Penn Machine Standard Abbreviations

Penn Machine Standard Abbreviations 1/25/2008 Arranged in Alphabetical Order Arranged in Abbreviation Alphabetical Order WORD ABBREVIATION ABBREVIATION WORD 10,000 Class 10M 45 45 degree elbow 150 Class 150 90 90 degree elbow 3000 Class 3M 150 150 Class 45 degree elbow 45 10M 10,000 Class 6000 Class 6M 3M 3000 Class 90 degree elbow 90 6M 6000 Class 9000 Class 9M 9M 9000 Class A A A105 Hot Dip Galvanized A105HDG A105 Carbon Steel A105N Hot Dipped Galvanized A105NHDG A105HDG A105 Hot Dipped Galvanized Adapter ADPT A105A Carbon Steel Annealed Amoco Pipe Plug w/groove AMOCO PL A105N Carbon Steel Normalized Annealed ANN A105NHDG A105 Normalized Hot Dipped Galvanized ASME Spec Defines Dimensions* B16.11 ADPT Adapter B AMOCO PL Amoco Pipe Plug w/groove Bevel Both Ends BBE ANN Annealed Bevel End Nipple Outlet BE NOL B Bevel x Plain BXP B/B Brass to Brass Bevel x Threaded BXT B/S Brass to Steel Blank BL B/S UN Brass to Steel Seat Union Branch Tee BRTEE B16.11 ASME Spec Defines Dimensions* Brass to Brass B/B BBE Bevel Both Ends Brass to Steel B/S BE NOL Bevel End Nipple Outlet Brass to Steel Seat Union B/S UN BL Blank Braze-on Outlet BOL BOL Braze-on Outlet British Standard Parallel Pipe BSPP BOSS Welding Boss British Standard Pipe Thread BST BRTEE Branch Tee British Standard Taper Pipe BSPT BSPP British Standard Parallel Pipe Buttweld BW BSPT British Standard Taper Pipe C BST British Standard Pipe Thread Cap CAP BXP Bevel x Plain Carbon Steel A105 BXT Bevel x Threaded Carbon Steel Annealed A105HT C Carbon Steel Normalized A105N CAP Cap Class 200