Challenges for Large‐Scale Land Concessions in Laos And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ho Chi Minh Trail Sec�Ons: the Ho Chi Minh Trail Was the Route from North Vietnam to South

JULY 2019 SUPPLEMENT VOL 82.5 Chapter 16 Newsleer Organizaon and Responsibilies: Editor: Glen Craig The Ho Chi Minh Trail Secons: The Ho Chi Minh Trail was the route from North Vietnam to South Message from the President: Stephen Durfee Vietnam thru Laos and Cambodia that North Vietnam used to Treasurers Report: Willi Lindner supply the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army in South Vietnam with Weapons, Ammuni on and other supplies. Sec. Rpt (Staff Meeng Minutes): Mike Barkstrom Sick Call/Obituary: Chaplain Butch Hall Blast from the Past: Glen Craig Special Recognion: Mike Barkstrom Upcoming Events: Mike Barkstrom Calendar: Stephen Durfee Human Interest Story: Chapter at large SFA Naonal HQ Update: Stephen Durfee Aer Acon Report: Jim Lessler Membership Info: Roy Sayer Adversements: Glen Craig Suspense: Newsleer published (Web): 1st of each odd numbered month Input due to editor: 20th of each even numbered month Dra due to President: 27th of each even numbered month Final Dra due 29th of each even numbered month I thought this was interesng and wanted to share it with everyone. I hope you enjoy it. Legend of the Ho Chi Minh Trail Ho Chi Minh Trail Aug14, 2012 Please ask, about our Ho Chi Minh Trail tours! Page 1 Ho Chi Minh trail, painng by Veteran Larry Chambers The Legend of the Ho Chi Minh trail, there are few brand names to match that of the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the secret, shiing, network of deep jungle tracks that led to the Victory for Vietnam war. SA 2 Surface to Air missile, Ho Chi Minh trail Southern Laos, Ho Chi Minh trail Huey helicopter used in the Lamson bale at the Ban Dong war museum Well here I sit in Laos again, I have been pung around the place on and off for 10 years now. -

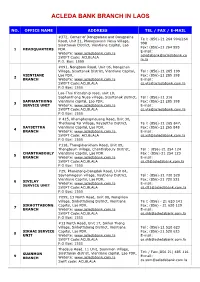

Acleda Bank Branch in Laos

ACLEDA BANK BRANCH IN LAOS NO. OFFICE NAME ADDRESS TEL / FAX / E-MAIL #372, Corner of Dongpalane and Dongpaina Te l: (856)-21 264 994/264 Road, Unit 21, Phonesavanh Neua Village, 998 Sisattanak District, Vientiane Capital, Lao Fax: (856)-21 264 995 1 HEADQUARTERS PDR. E-mail: Website: www.acledabank.com.la [email protected] SWIFT Code: ACLBLALA m.la P.O. Box: 1555 #091, Nongborn Road, Unit 06, Nongchan Village, Sisattanak District, Vientiane Capital, Tel : (856)-21 285 199 VIENTIANE Lao PDR. Fax: (856)-21 285 198 2 BRANCH Website: www.acledabank.com.la E-mail: SWIFT Code:ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 Lao-Thai friendship road, unit 10, Saphanthong Nuea village, Sisattanak district, Tel : (856)-21 316 SAPHANTHONG Vientiane capital, Lao PDR. Fax: (856)-21 285 198 3 SERVICE UNIT Website: www.acledabank.com.la E-mail: SWIFT Code:ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 # 415, Khamphengmeuang Road, Unit 30, Thatluang Tai Village, Xaysettha District, Te l: (856)-21 265 847, XAYSETTHA Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR. Fax: (856)-21 265 848 4 BRANCH Website: www.acledabank.com.la, E-mail: SWIFT Code: ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 #118, Thongkhankham Road, Unit 09, Thongtoum Village, Chanthabouly District, Tel : (856)-21 254 124 CHANTHABOULY Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR Fax : (856)-21 254 123 5 BRANCH Website: www.acledabank.com.la E-mail: SWIFT Code:ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 #29, Phonetong-Dongdok Road, Unit 04, Saynamngeun village, Xaythany District, Tel : (856)-21 720 520 Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR. -

Rra Report Attapeu Watershed Attapeu

Page 1 of 9 ADB RETA 5771 Poverty Reduction & Environmental Management in Remote Greater Mekong Subregion Watersheds Project (Phase I) RRA REPORT ATTAPEU WATERSHED ATTAPEU & CHAMPASSACK PROVINCE, LAO PDR Special Report By Latsamay Sylavong 1. General Background Attapeu watershed is located in the Southern part of Lao PDR. This watershed is covered in 2 provinces as the whole of Attapeu province and a small part of Champassack provinces (the Plateau Boloven). There are about 900 Kilometres from Vientiane Municipality and 180 kilometres from Pakse. Access to those 4 villages differs from one to another village due to the selection criteria for the RRA survey in order to cover the main ethnic minorities in the watershed area. It is found easy access to 2 villages of Champassack province (Boloven Plateau) for both seasons and very difficult to get to other 2 villages of Attapeu province, especially during raining season. The purpose of this survey is to describe the existing agroecosystems within the watershed area as the relationship to the use of forest resource by human population. In addition, Attapeu watershed is one of the shortlist watersheds priorities in Lao PDR. In the Attapeu watershed 4 villages were studied and detailed information of demographic survey in different ethnic villages as Nha Heune, Alak, Laven and Chung. The number of villages depends on the time available for this survey and the difficulty in access within this area, and the time spending at each village also depends on the size of the village. All 4 villages were selected by the survey team together with the local authorities of both provinces as Champassack and Attapeu. -

8Th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO- ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN

Lao People’s Democratic Republic Peace Independence Unity Prosperity 8th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO- ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2016–2020) (Officially approved at the VIIIth National Assembly’s Inaugural Session, 20–23 April 2016, Vientiane) Ministry of Planning and Investment June 2016 8th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2016–2020) (Officially approved at the VIIIth National Assembly’s Inaugural Session, 20–23 April 2016, Vientiane) Ministry of Planning and Investment June 2016 FOREWORD The 8th Five-Year National Socio-economic Development Plan (2016–2020) “8th NSEDP” is a mean to implement the resolutions of the 10th Party Conference that also emphasizes the areas from the previous plan implementation that still need to be achieved. The Plan also reflects the Socio-economic Development Strategy until 2025 and Vision 2030 with an aim to build a new foundation for graduating from LDC status by 2020 to become an upper-middle-income country by 2030. Therefore, the 8th NSEDP is an important tool central to the assurance of the national defence and development of the party’s new directions. Furthermore, the 8th NSEDP is a result of the Government’s breakthrough in mindset. It is an outcome- based plan that resulted from close research and, thus, it is constructed with the clear development outcomes and outputs corresponding to the sector and provincial development plans that should be able to ensure harmonization in the Plan performance within provided sources of funding, including a government budget, grants and loans, -

Mapping Context of Land Use for a Non-Traditional Agricultural Export

Land grabbing, conflict and agrarian‐environmental transformations: perspectives from East and Southeast Asia An international academic conference 5‐6 June 2015, Chiang Mai University Conference Paper No. 75 Mapping context of land use for a non-traditional agricultural export (NTAE) product: case study of land use for coffee plantation in Pakxong district, Champasak province, Lao PDR Saithong Phommavong, Kiengkai Ounmany and Keophouthone Hathalong June 2015 BICAS www.plaas.org.za/bicas www.iss.nl/bicas In collaboration with: Demeter (Droits et Egalite pour une Meilleure Economie de la Terre), Geneva Graduate Institute University of Amsterdam WOTRO/AISSR Project on Land Investments (Indonesia/Philippines) Université de Montréal – REINVENTERRA (Asia) Project Mekong Research Group, University of Sydney (AMRC) University of Wisconsin-Madison With funding support from: Mapping context of land use for a non‐traditional agricultural export (NTAE) product: case study of land use for coffee plantation in Pakxong district, Champasak province, Lao PDR by Saithong Phommavong, Kiengkai Ounmany and Keophouthone Hathalong Published by: BRICS Initiatives for Critical Agrarian Studies (BICAS) Email: [email protected] Websites: www.plaas.org.za/bicas | www.iss.nl/bicas MOSAIC Research Project Website: www.iss.nl/mosaic Land Deal Politics Initiative (LDPI) Email: [email protected] Website: www.iss.nl/ldpi RCSD Chiang Mai University Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University Chiang Mai 50200 THAILAND Tel. 6653943595/6 | Fax. 6653893279 Email : [email protected] | Website : http://rcsd.soc.cmu.ac.th Transnational Institute PO Box 14656, 1001 LD Amsterdam, The Netherlands Tel: +31 20 662 66 08 | Fax: +31 20 675 71 76 Email: [email protected] | Website: www.tni.org June 2015 Published with financial support from Ford Foundation, Transnational Institute, NWO and DFID. -

UXO/Mine Action in Lao PDR

2014 ANNUAL REPORT This document acts as Annual Report of the National Regulatory Authority for UXO/Mine Action in Lao PDR. For further information, please contact the: National Regulatory Authority for UXO/Mine Action Sector in Lao PDR (NRA) Sisangvone Village, P.O. Box 7621, Unit 19, Saysettha District, Vientiane, Lao PDR Website: www.nra.gov.la Telephone: (856-21) 262386 Donation for UXO victims: your support can make a difference. Your contribution to the National Regulatory Authority for UXO/Mine Action in Lao PDR can support for families and children whose lives have been suffered by the UXO from the Indo-China War. For how to give, please contact Victim Assistance Unit of the National Regulatory Authority for UXO/Mine Action in Lao PDR, Mr. Bountao Chanthavongsa via email: [email protected] Compiled and designed by: Vilavong SYSAVATH and Olivier BAUDUIN Photos: Photos that appear in the Operator Reports, unless individually credited, were taken by and are the property of that Operator. All other photos in this report, unless individually creditied, have been taken by the following people - Vilavong SYSAVATH Acknowledgements: The NRA would like to thank all UXO/Mine Action Sector Operators who provided images and information on their projects and activities in 2014 for this report. The NRA Programme and Public Relations Unit would also like to acknowledge the support and effort put in by all Members of the NRA team in helping to compile the UXO Sector Annual Report 2014. This report may be subject to change after publication. To find out more about changes, errors, or omissions please visit the website: www.nra.gov.la. -

Potential Economic Corridors Between Vietnam and Lao PDR: Roles Played by Vietnam

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Potential economic corridors between Vietnam and Lao PDR: Roles played by Vietnam Nguyen, Binh Giang IDE-JETRO 2012 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/40502/ MPRA Paper No. 40502, posted 06 Aug 2012 12:14 UTC CHAPTER 3 Potential Economic Corridors between Vietnam and Lao PDR: Roles Played by Vietnam Nguyen Binh Giang This chapter should be cited as: NGUYEN, Bing Giang 2012. “Potential Economic Corridors between Vietnam and Lao PDR: Roles Played by Vietnam” in Emerging Economic Corridors in The Mekong Region, edited by Masami Ishida, BRC Research Report No.8, Bangkok Research Center, IDE-JETRO, Bangkok, Thailand. CHAPTER 3 POTENTIAL ECONOMIC CORRIDORS BETWEEN VIETNAM AND LAO PDR: ROLES PLAYED BY VIETNAM Nguyen Binh Giang INTRODUCTION The Third Thai-Lao Friendship Bridge over the Mekong River officially opened on November 11, 2011, facilitating cross-border trade along Asian Highway (AH) 15 (Route No. 8) and AH 131 (Route No. 12) between northeast Thailand, central Lao PDR and North Central Vietnam. Since the establishment of the East-West Economic Corridor (EWEC) which is based on AH 16 (Route No. 9), the cross-border trade among countries in the Greater Mekong Sub-region has been much facilitated. The success of EWEC encourages local governments in the region to establish other economic corridors. Currently, it seems that there are ambitions to establish parallel corridors with EWEC. The basic criteria for these corridors is the connectivity of the Thailand-Lao PDR or Lao PDR-Vietnam border gates, major cities in northeast Thailand, south and central Lao PDR, and North Central and Middle Central Vietnam, and ports in Vietnam by utilizing some existing Asian Highways (AHs) or national highways. -

CARE Lao PDR Women Organized for Rural Development

CARE Lao PDR Women Organized for Rural Development Australian NGO Cooperation Program Endline Evaluation Report May-June 2017 Dr. Antonella Diana 1 Table of Contents Abbreviations 1 Executive Summary 4 Acknowledgments 10 Introduction 11 Scope and Context of the Project 11 Methodology 15 Findings and Analysis 18 Objective 1: To promote remote ethnic women’s collective actions through income-generating activities 18 Objective 2: To strengthen CBOs and NPAs to enable them to support and represent remote ethnic women 45 Objective 3: To enhance linkages between learning, programming and policy influencing 59 Lessons learned 61 Recommendations 65 List of references 69 Annexes 70 2 Abbreviations ANCP Australian NGO Cooperation Program CBOs community based organizations CPG Coffee Production/Processing Groups DAFO District Agriculture and Forestry Office DHO District Health Office FC Farming Cooperative FG Farmer Groups FGD focus group discussions FPG Farmers’ Production Groups GoL Government of Laos GBV Gender Based Violence IGA Income Generating Activities LDPA Lao Disabled People Association (Sekong) LTP long-term program LWU Lao Women Union NPAs Non Profit Associations PAFO Provincial Agriculture and Forestry Office POFA Provincial Foreign Affairs Office PPCA Partner’s Participatory Capacity Assessment PWED Partnership for Poverty Reduction and Women’s Empowerment REW Remote Ethnic Women SAEDA Sustainable Agriculture and Environment Development Association (Phongsaly) VSLA Village Savings and Loan Associations WINGs Women Interests and Nutrition Groups 3 Executive Summary The 3-year (2014 – 2017) Women Organised for Rural development (WORD) project aimed to ensure benefits to remote ethnic women (REW) and their communities through strengthening community-led farmers and women’s groups (community based organisations - CBOs) in order to strengthen REW livelihoods and foster demand driven service delivery that would sustain beyond the project duration. -

Basic Education (Girls) Project

Completion Report Project Number: 29288 Loan Number: 1621 July 2008 Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Basic Education (Girls) Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit – kip (KN) At Appraisal At Project Completion 30 April 1998 31 July 2007 KN1.00 = $0.000419 $0.000104 $1.00 = KN2,383.50 KN9,550 ABBREVIATIONS CCED – committee for community education and development DEB – district education bureau DNFE – Department of Non-Formal Education EA – executing agency EMIS – education management information system EQIP – Education Quality Improvement Project GDP – gross domestic product GEMEU – Gender and Ethnic Minorities Education Unit Lao PDR – Lao People’s Democratic Republic MOE – Ministry of Education NGO – nongovernment organization NRIES – National Research Institute for Educational Science PES – provincial education service PWG – project working group RRP – report and recommendation of the President TA – technical assistance TTC – teacher training center NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government ends on 30 September. FY before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends, e.g., FY2008 ends on 30 September 2008. (ii) In this report, “$” refers to US dollars Vice President C. Lawrence Greenwood, Jr. Operations 2 Director General A. Thapan, Southeast Asia Department (SERD) Director G.H. Kim, Lao Resident Mission (LRM), SERD Team leader K. Chanthy, Senior Project Implementation Officer, LRM, SERD Team member S. Souannavong, Assistant Project Analyst, LRM, SERD iii CONTENTS Page BASIC DATA i I. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 1 II. EVALUATION OF DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION 2 A. Relevance of Design and Formulation 2 B. Project Outputs 4 C. Project Costs 7 D. Disbursements 7 E. Project Schedule 7 F. -

Travel Time and Distance

TRAVEL TIME AND DISTANCE Location Distance Time needed Remarks International Pakse – Bangkok 720 kms By air: 2 hrs 30 5 flights a week Pakse – Siem Reap 530 kms By air: 1 hr 3 flights a week Pakse – Hochiminh Ville 587 kms By air:1 hr 35 3 flights a week Daily flights via Nok Bangkok – Ubon Ratchathani 637 kms By air: 1 hr 15 Air, Lion Air, Air Asia Pakse – Vang Tao (Thailand) 53 kms By road: 1 hr 5 flights a week Vang Tao - Pakse 94 kms By road: 1 hr Pakse – Ubon Ratchathani (Thailand) 147 kms By road: 2 hrs Pakse – Nong Nok Khien (Cambodia) 168 kms By road: 3 hrs 20 Attapeu – Phou Keua (Vietnam) 113 kms By road: 1 hr 30 National By air: 1 hr 15 Pakse – Vientiane Capital 680 kms Daily flights By road: 8 hrs 30 3 direct flights a By air: 1 hr 40 Pakse – Luang Phabang 1,082 kms week or daily flights By road: 13 hrs via Vientiane By air: 30 min Pakse – Savannakhet 251 kms 5 flights a week By road: 3 hrs Pakse – Saravan (via Paksong) 152 kms By road: 2 hrs Pakse – Saravan (via Road 13) 112 kms By road: 1 hr 15 Pakse – Tad Lo (Saravan) 85 kms By road: 1 hr 15 Pakse – Ban Houay Houn 50 kms By road: 1 hr Pakse – Sekong 140 kms By road: 2 hrs 30 Sekong – Ban Kan Done 25 kms By road: 30 min Not possible during Sekong – Dakcheung district 130 kms By road: 6 to 8 hrs rainy season Pakse – Attapeu 212 kms By road: 4 hrs 30 Attapeu – Tha Hine village 3 kms By road: 10 min Pakse – Champasak district 38 kms By road: 40 min Pakse – Vat Phou 43 kms By road: 50 min Pakse – Paksong district 51 kms By road: 1 h Pakse – Tad Fan 38 kms By road: 45 min Pakse -

Laos, Thailand and Myanmar (Burma)

Explosive Remnants of War: A Case Study of Explosive Ordnance Disposal in Laos, 1974-2013 Anna F. Kemp A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Greenwich for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2014 i DECLARATION I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised another’s work. ___________________________ ___________________ Anna Kemp Date Student ___________________________ ___________________ Professor Christopher Bellamy Date First Supervisor ___________________________ __________________ Dr Christopher Ware Date Second Supervisor ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis has greatly profited by the influence and support of many individuals. First and foremost, I wish to express my gratitude to Cranfield University at Shrivenham U.K. I am profoundly grateful to Professor Christopher Bellamy, both at Cranfield and Greenwich, for his contribution to my intellectual growth and unstinting inspiration in tackling a thesis on UXO, plus the encouraging discussions about the problems which have been treated in this work, and answering constant and probably banal questions from a student, who never served in the armed forces. After Professor Bellamy moved to Greenwich, no-one suitably qualified to supervise my research remained at Cranfield and I, too, transferred. I am also grateful to Professor Alan Reed, Chair of the University of Greenwich Research Degrees Committee for easing that process. -

Ngos in the GMS Involvement Related to Poverty Alleviation and Watershed Management Lao PDR

Page 1 of 9 Regional Environmental Technical Assistance 5771 Poverty Reduction & Environmental Management in Remote Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Watersheds Project (Phase I) NGOs IN THE GMS Involvement Related to Poverty Alleviation and Watershed Management Lao PDR By Gunilla Riska CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 3 2 GENERAL 3 3 LEGAL FRAMEWORK 3 4 COORDINATION 4 4.1 Government-NGOs 4 4.2 Networking among the NGOs 4 5 ROLE OF NGOs 6 5.1 International NGOs 6 5.2 International NGOs at selected watersheds 7 5.3 Local organisations 10 6 CONCLUSIONS 11 6.1 General Conclusions 11 6.2 Co-operation with RETA 5771 12 REFERENCES 14 Page 2 of 9 1 INTRODUCTION The review of NGOs working with poverty alleviation and watershed management in some selected watershed areas, has been done within the limited time of a short -term consultancy. The aim is to get an understanding of the development of NGOs in Lao PDR to-day, with an aim to find organisations of interest for the project in its second planning phase and during implementation. 2 GENERAL The main increase in international NGO assistance occurred after the adoption of the New Economic Mechanism (NEM) by the Government of Lao PDR in 1986. Although the Constitution of 1991 approves of the establishment of associations and organisations local NGOs are not officially recognised. The Government officially acknowledges the importance of international NGOs and their possibilities in reaching vulnerable populations with efficient interventions, however, some mistrust still exist. The number of international NGOs in Lao PDR is growing slowly compared to the situation in e.g.