Baseline Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acleda Bank Branch in Laos

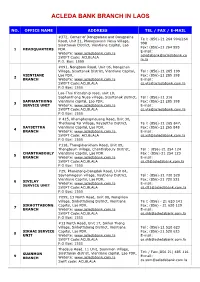

ACLEDA BANK BRANCH IN LAOS NO. OFFICE NAME ADDRESS TEL / FAX / E-MAIL #372, Corner of Dongpalane and Dongpaina Te l: (856)-21 264 994/264 Road, Unit 21, Phonesavanh Neua Village, 998 Sisattanak District, Vientiane Capital, Lao Fax: (856)-21 264 995 1 HEADQUARTERS PDR. E-mail: Website: www.acledabank.com.la [email protected] SWIFT Code: ACLBLALA m.la P.O. Box: 1555 #091, Nongborn Road, Unit 06, Nongchan Village, Sisattanak District, Vientiane Capital, Tel : (856)-21 285 199 VIENTIANE Lao PDR. Fax: (856)-21 285 198 2 BRANCH Website: www.acledabank.com.la E-mail: SWIFT Code:ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 Lao-Thai friendship road, unit 10, Saphanthong Nuea village, Sisattanak district, Tel : (856)-21 316 SAPHANTHONG Vientiane capital, Lao PDR. Fax: (856)-21 285 198 3 SERVICE UNIT Website: www.acledabank.com.la E-mail: SWIFT Code:ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 # 415, Khamphengmeuang Road, Unit 30, Thatluang Tai Village, Xaysettha District, Te l: (856)-21 265 847, XAYSETTHA Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR. Fax: (856)-21 265 848 4 BRANCH Website: www.acledabank.com.la, E-mail: SWIFT Code: ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 #118, Thongkhankham Road, Unit 09, Thongtoum Village, Chanthabouly District, Tel : (856)-21 254 124 CHANTHABOULY Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR Fax : (856)-21 254 123 5 BRANCH Website: www.acledabank.com.la E-mail: SWIFT Code:ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 #29, Phonetong-Dongdok Road, Unit 04, Saynamngeun village, Xaythany District, Tel : (856)-21 720 520 Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR. -

Rra Report Attapeu Watershed Attapeu

Page 1 of 9 ADB RETA 5771 Poverty Reduction & Environmental Management in Remote Greater Mekong Subregion Watersheds Project (Phase I) RRA REPORT ATTAPEU WATERSHED ATTAPEU & CHAMPASSACK PROVINCE, LAO PDR Special Report By Latsamay Sylavong 1. General Background Attapeu watershed is located in the Southern part of Lao PDR. This watershed is covered in 2 provinces as the whole of Attapeu province and a small part of Champassack provinces (the Plateau Boloven). There are about 900 Kilometres from Vientiane Municipality and 180 kilometres from Pakse. Access to those 4 villages differs from one to another village due to the selection criteria for the RRA survey in order to cover the main ethnic minorities in the watershed area. It is found easy access to 2 villages of Champassack province (Boloven Plateau) for both seasons and very difficult to get to other 2 villages of Attapeu province, especially during raining season. The purpose of this survey is to describe the existing agroecosystems within the watershed area as the relationship to the use of forest resource by human population. In addition, Attapeu watershed is one of the shortlist watersheds priorities in Lao PDR. In the Attapeu watershed 4 villages were studied and detailed information of demographic survey in different ethnic villages as Nha Heune, Alak, Laven and Chung. The number of villages depends on the time available for this survey and the difficulty in access within this area, and the time spending at each village also depends on the size of the village. All 4 villages were selected by the survey team together with the local authorities of both provinces as Champassack and Attapeu. -

8Th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO- ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN

Lao People’s Democratic Republic Peace Independence Unity Prosperity 8th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO- ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2016–2020) (Officially approved at the VIIIth National Assembly’s Inaugural Session, 20–23 April 2016, Vientiane) Ministry of Planning and Investment June 2016 8th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2016–2020) (Officially approved at the VIIIth National Assembly’s Inaugural Session, 20–23 April 2016, Vientiane) Ministry of Planning and Investment June 2016 FOREWORD The 8th Five-Year National Socio-economic Development Plan (2016–2020) “8th NSEDP” is a mean to implement the resolutions of the 10th Party Conference that also emphasizes the areas from the previous plan implementation that still need to be achieved. The Plan also reflects the Socio-economic Development Strategy until 2025 and Vision 2030 with an aim to build a new foundation for graduating from LDC status by 2020 to become an upper-middle-income country by 2030. Therefore, the 8th NSEDP is an important tool central to the assurance of the national defence and development of the party’s new directions. Furthermore, the 8th NSEDP is a result of the Government’s breakthrough in mindset. It is an outcome- based plan that resulted from close research and, thus, it is constructed with the clear development outcomes and outputs corresponding to the sector and provincial development plans that should be able to ensure harmonization in the Plan performance within provided sources of funding, including a government budget, grants and loans, -

Mapping Context of Land Use for a Non-Traditional Agricultural Export

Land grabbing, conflict and agrarian‐environmental transformations: perspectives from East and Southeast Asia An international academic conference 5‐6 June 2015, Chiang Mai University Conference Paper No. 75 Mapping context of land use for a non-traditional agricultural export (NTAE) product: case study of land use for coffee plantation in Pakxong district, Champasak province, Lao PDR Saithong Phommavong, Kiengkai Ounmany and Keophouthone Hathalong June 2015 BICAS www.plaas.org.za/bicas www.iss.nl/bicas In collaboration with: Demeter (Droits et Egalite pour une Meilleure Economie de la Terre), Geneva Graduate Institute University of Amsterdam WOTRO/AISSR Project on Land Investments (Indonesia/Philippines) Université de Montréal – REINVENTERRA (Asia) Project Mekong Research Group, University of Sydney (AMRC) University of Wisconsin-Madison With funding support from: Mapping context of land use for a non‐traditional agricultural export (NTAE) product: case study of land use for coffee plantation in Pakxong district, Champasak province, Lao PDR by Saithong Phommavong, Kiengkai Ounmany and Keophouthone Hathalong Published by: BRICS Initiatives for Critical Agrarian Studies (BICAS) Email: [email protected] Websites: www.plaas.org.za/bicas | www.iss.nl/bicas MOSAIC Research Project Website: www.iss.nl/mosaic Land Deal Politics Initiative (LDPI) Email: [email protected] Website: www.iss.nl/ldpi RCSD Chiang Mai University Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University Chiang Mai 50200 THAILAND Tel. 6653943595/6 | Fax. 6653893279 Email : [email protected] | Website : http://rcsd.soc.cmu.ac.th Transnational Institute PO Box 14656, 1001 LD Amsterdam, The Netherlands Tel: +31 20 662 66 08 | Fax: +31 20 675 71 76 Email: [email protected] | Website: www.tni.org June 2015 Published with financial support from Ford Foundation, Transnational Institute, NWO and DFID. -

Travel Time and Distance

TRAVEL TIME AND DISTANCE Location Distance Time needed Remarks International Pakse – Bangkok 720 kms By air: 2 hrs 30 5 flights a week Pakse – Siem Reap 530 kms By air: 1 hr 3 flights a week Pakse – Hochiminh Ville 587 kms By air:1 hr 35 3 flights a week Daily flights via Nok Bangkok – Ubon Ratchathani 637 kms By air: 1 hr 15 Air, Lion Air, Air Asia Pakse – Vang Tao (Thailand) 53 kms By road: 1 hr 5 flights a week Vang Tao - Pakse 94 kms By road: 1 hr Pakse – Ubon Ratchathani (Thailand) 147 kms By road: 2 hrs Pakse – Nong Nok Khien (Cambodia) 168 kms By road: 3 hrs 20 Attapeu – Phou Keua (Vietnam) 113 kms By road: 1 hr 30 National By air: 1 hr 15 Pakse – Vientiane Capital 680 kms Daily flights By road: 8 hrs 30 3 direct flights a By air: 1 hr 40 Pakse – Luang Phabang 1,082 kms week or daily flights By road: 13 hrs via Vientiane By air: 30 min Pakse – Savannakhet 251 kms 5 flights a week By road: 3 hrs Pakse – Saravan (via Paksong) 152 kms By road: 2 hrs Pakse – Saravan (via Road 13) 112 kms By road: 1 hr 15 Pakse – Tad Lo (Saravan) 85 kms By road: 1 hr 15 Pakse – Ban Houay Houn 50 kms By road: 1 hr Pakse – Sekong 140 kms By road: 2 hrs 30 Sekong – Ban Kan Done 25 kms By road: 30 min Not possible during Sekong – Dakcheung district 130 kms By road: 6 to 8 hrs rainy season Pakse – Attapeu 212 kms By road: 4 hrs 30 Attapeu – Tha Hine village 3 kms By road: 10 min Pakse – Champasak district 38 kms By road: 40 min Pakse – Vat Phou 43 kms By road: 50 min Pakse – Paksong district 51 kms By road: 1 h Pakse – Tad Fan 38 kms By road: 45 min Pakse -

The Study on Power Network System Plan in Lao People's Democratic

Department of Electricity, Ministry of Energy and Mines Electricité du Laos Lao People’s Democratic Republic The Study on Power Network System Plan in Lao People’s Democratic Republic Final Report January 2010 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY Tokyo Electric Power Company, Inc. Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. IDD JR 09-090 PREFACE In response to a request from the Government of Lao People’s Democratic Republic, the Government of Japan decided to conduct “The Study on Power Network System Plan in Lao People’s Democratic Republic” which was entrusted to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA selected and dispatched between October 2008 and January 2010 a study team headed by Mr. Masaharu YOGO of Tokyo Electric Power Company, Inc. (TEPCO) comprised of TEPCO and Nippon Koei Co., Ltd.. The team held discussions with concerned officials from the Government of Lao People’s Democratic Republic and conducted field surveys. Upon returning to Japan, further studies were conducted and a final report was prepared. The power network system plan up to 2030 has been formulated taking into consideration the situations of both the power sector and LAO PDR’s existing power facilities in this study. An evaluation of the prioritization of the projects for power network development has been conducted. The highest prioritized project’s, facility design and validity was confirmed and a cost estimation was conducted. I hope that this report will contribute to power network system planning in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic as well as enhancing the friendly relationship between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials representing the Government of Lao People’s Democratic Republic for their unwavering cooperation in support of this study. -

Lao Coffee Development/Promotion Strategy to 2025, Page 1

Lao Coffee Development/promotion Strategy to 2025, Page 1 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 3 Part I. Evaluation of the Lao Coffee Production Status in the Past ....................................... 4 1.1 Previous Lao Coffee Development Policy ..................................................................................... 4 1.2 Previous Lao PDR Coffee Production Conditions ............................................................................. 4 1.3. Reasons for Success ..................................................................................................................... 6 1.4. Major issues and constraints to be addressed ............................................................................. 7 1.5. Lessons Learned ........................................................................................................................... 8 1.6. Environmental Expectation and Future Challenges ..................................................................... 9 Part II: Sector’s Objectives and strategic vision ....................................................................... 11 2.1. Vision .......................................................................................................................................... 11 2.2. Objectives ................................................................................................................................... 12 2.3. Improvement -

Champasak Province

- 2 0 1 0 2 0 0 9 Investment Opportunities in LAOS CHAMPASAK PROVINCE Champasak Province Sky-rocketing FDIs since 2000 Untapped business potentials Strategic Location “The emerging Resource rich – low cost investment destina- Attractive Incentives tion in South East One Stop Shop Service Unit Asia” Conducive Investment Climate TABLE of CONTENTS Welcoming Address by the Governor 3 Champasak Province: Dynamism and Profile of the Local Economy 4 Geographic Location & Economic Data 5 Investment Climate 6 Foreign Direct Investment 7 Economic Map of Champasak Province 8 Foreign and Domestic Investment Calling List 9 Priority Investment Areas: Tourism, Agri-Business, Industry 12 Investment Incentives 16 Overview of Facilities and Costs 17 Human Resources 19 Financial Services 21 22 Quality of Life Official Agencies in Champasak Province 23 Welcoming Address by the Governor of Champasak Province s a result of the implementation of the socio-economic development A plan in the fiscal year 2007/2008, Champasak Province has seen an over- all increasing trend: Estimated income per capita rose from US$ 606 in 2006/2007 to US$ 730 in 2007/2008. At provincial level, poverty rate remains at 5% of a total of 107,092 families. In addition the GDP growth rate over the last ten years is very promising. Macro-economic indicators, embracing government‘s policies and objectives - have accomplished a considerable satisfactory level. Governor of Champasak Province Champasak Province authority in particular works hard to reduce poverty and to improve livelihood in rural areas. Provincial leaders together with departments, committees and relevant sectors, as well as the central government bodies, have put all their efforts in seeking additional funds for the provincial budget and utilizing all means for in- vestments into some fundamental infrastructures. -

Remote Village Education Support Project, Pathoumphone District

Remote Village Education Support Project Pathoumphone District, Champasak Province, Lao PDR Village Survey Report May 10 - 20, 2001 Prepared by Monty Sly Global Association for People and the Environment P.O. Box 860, Pakse, Lao PDR e-mail: [email protected] 2 Introduction This report was prepared after completion of a survey of ten remote villages in Pathoumphone district, Champasak province, Lao PDR, between May 10th and 20th, 2001. During consultations between representatives of the Canadian non- government organization the Global Association for People and the Environment (GAPE) and Champasak provincial education officials, Pathoumphone district was identified as one of the two districts of Champasak province with the most pressing education problems. These include a low percentage of students in school, irregular attendance, teachers who are too often absent, lack of education materials, and poor condition of schools. Villages located in other districts of Champasak province, such as those along the Mekong river, including Khong district, Pakse district and Phonthong district are not as cut-off and isolated as many of the villages in Pathoumphone district, and thus have higher numbers of students in school, better access to educational materials, and more regular teachers. We expressed our interest in providing educational support, especially to remote villages which do not have year round road access, and thus likely have more than their share of education problems. Ten remote villages in Pathoumphone district were selected to be -

Lao People's Democratic Republic

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC: SUSTAINABLE COMMERCIALISATION IN THE COFFEE VALUE CHAIN FOSTERING THE DEVELOPMENT OF GREEN EXPORTS THROUGH VOLUNTARY SUSTAINABILITY STANDARDS © 2020, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development This work is available open access by complying with the Creative Commons licence created for intergovernmental organizations, available at http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/3.0/igo/. In line with this license, material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint to be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or its officials or Member States. The designation employed and the presentation of material on any map in this work do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This publication has not been formally edited. UNCTAD/DITC/TAB/INF/2020/2 I ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study is part of UNCTAD’s efforts to tackle vulnerabilities and build resilience in small and vulnerable economies, while prompting structural diversification and upgrading. It strengthens national capacities to design and implement complementary trade and agricultural policies supportive of small scale and subsistence-oriented farmers, including female farmers and vulnerable groups, and supportive of local food security. It provides evidence-based analysis that feeds national, regional and international policies with the aim of generating inclusive sustainable development. -

The World Bank

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized ReportNo. 2842-LA LAO PEOPLE'S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC Public Disclosure Authorized AGRICULTURALREHABILITATION AND DEVELOPMENTPROJECT III STAFF APPRAISAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized April 18, 1980 Public Disclosure Authorized Projects Department East Asia and Pacific Regional Office This documenthas a restricteddistribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit = New Kip (NK1) NK 1.00 = $0.10 $1.00 = NK 10 NK 1.0 million = $100,000 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES Metric System 1 kilogram (kg) = 2.20 lb 1 metric ton (1,000 kg) = 0.98 long tons 1 kilometer (km) = 0.62 miles 1 hectare (ha) = 2.47 acres ABBREVIATIONS AN» ACRONYMS DIC - Department of Industry and Commerce (Province? DLI - Department of Light Industry (MIC) DOA - Department of Agriculture (MOA and Province) DOC - Department of Cooperatives and State Farms (MDA and Province) DOE - Department of Equipment (MPW) DOI - Department of Irrigation (MOA) DPW - Department of Public Works (Province) EDL - Electricity Department of Laos (MIC) MIC - Ministry of Industry and Commerce MOA - Ministry of Agriculture lIPW - Ministry of Public Works PEC - Provincial Executive Committee ADB - Asian Development Bank FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization SIDA - Swedish International Development Authority UNCDF - United Nations Capital Development Fund UNDP - United Nations Development Program LAO DESIGNATIONS Khoueng - Province Muong - District Tasseng - Subdistrict Ban - Village Houei - River GOVERNMENT OF LAO PDR FISCAL YFAR January 1 - December 31 FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY LAO PEOPLE'S DEMOCRATICREPUBLIC AGRICULTURALREHABILITATION AND DEVELOPMENTPROJECT III STAFF APPRAISAL REPORT Table of Contents Page No. -

Agriculture Development Strategy to 2025 and Vision to 2030

Agriculture Development Strategy to 2025 and Vision to the year 2030 Sectoral Vision and Aims “Ensuring food security, producing comparative and competitive agricultural commodities, developing clean, safe and sustainable agriculture and shift gradually to the modernization of a resilient and productive agriculture economy linking with rural development contributing to the national economic basis” Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry May 2015 Lao People’s Democratic Republic Peace Independence Democracy Unity Prosperity Government No. 53/GoV Vientiane Capital, dated 20-2-2015 Decree on Endorsement and Declaration of the Agriculture Development Strategy to the year 2025 and Vision to the year 2030 Pursuant to the Law of the Government of the Lao PDR No. 02/NA, dated 6 May 2003. Pursuant to the Decision of the Lao Government regular monthly Conference of May 2015 No. 06/GoL, dated 02 July 2014. With reference to the proposal of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry No. 1258/MAF, dated 26 August 2014. The Government issues Decree: Article 1: To officially endorse and declare the “Agriculture Development Strategy to the year 2025 and Vision to the year 2030”. Article 2: To authorize the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry in collaboration with concerned ministries-equivalent organizations and local authorities to effectively study, enhance and implement the Agriculture Development Strategy to the year 2025 and Vision to the year 2030. Article 3: The concerned Ministries, Ministerial equivalent Organizations, Vientiane Capital, Provinces and other concerned organizations to aware, accept and implement this Decree strictly and effectively. Article 4: This Decree shall enter into force from the date it is signed.