Lao People's Democratic Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ho Chi Minh Trail from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Ho Chi Minh trail From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Hồ Chí Minh trail (also known in Vietnam as the "Trường Sơn trail") was a logistical system that ran from the Hồ Chí Minh Trail Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) to the Southeastern Laos Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) through the neighboring kingdoms of Laos and Cambodia. The system provided support, in the form of manpower and materiel, to the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (called the Vietcong or "VC" by its opponents) and the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN), or North Vietnamese Army, during the Vietnam War. It was named by the Americans after North Vietnamese president Hồ Chí Minh. Although the trail was mostly in Laos, the communists called it the Trường Sơn Strategic Supply Route (Đường Trường Sơn), after the Vietnamese name for the Annamite Range mountains in central Vietnam.[1] According to the United States National Security Agency's official history of the war, the Trail system was "one of the great achievements of military engineering of the 20th century."[2] Contents 1 Origins (1959–1965) Ho Chi Minh Trail, 1967 Type Logistical system 1.1 Base areas Site information 2 Interdiction and expansion (1965–1968) Controlled by National Liberation Front 2.1 Air operations against the trail Site history 2.2 Ground operations against the trail Built 1959–1975 3 Commando Hunt (1968–1970) In use 1959–1975 Battles/wars Operation Barrel Roll 3.1 Fuel pipeline Operation Steel Tiger 3.2 Truck relay system Operation Tiger Hound Operation Commando Hunt 4 Road to PAVN victory (1971–75) Cambodian Incursion Operation Lam Son 719 5 See also Ho Chi Minh Campaign 6 Notes Operation Left Jab Operation Honorable Dragon Operation Diamond Arrow 7 Sources Project Copper Operation Phiboonpol Operation Sayasila Origins (1959–1965) Operation Bedrock Operation Thao La Parts of what became the trail had existed for centuries as Operation Black Lion primitive footpaths that facilitated trade. -

2019 FAO/WFP Crop and Food Security Assessment Mission to the Lao People's Democratic Republic

ISSN 2707-2479 SPECIAL REPORT 2019 FAO/WFP CROP AND FOOD SECURITY ASSESSMENT MISSION (CFSAM) TO THE LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC 9 April 2020 SPECIAL REPORT 2019 FAO/WFP CROP AND FOOD SECURITY ASSESSMENT MISSION (CFSAM) TO THE LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC 9 April 2020 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME Rome, 2020 Required citation: FAO. 2020. Special Report - 2019 FAO/WFP Crop and Food Security Assessment Mission to the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/ca8392en The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISSN 2707-2479 [Print] ISSN 2707-2487 [Online] ISBN 978-92-5-132344-1 [FAO] © FAO, 2020 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode). -

Gender and Social Inclusion Analysis (Gsia) Usaidlaos Legal Aid Support

GENDER AND SOCIAL INCLUSION ANALYSIS (GSIA) USAID LAOS LEGAL AID SUPPORT PROGRAM The Asia Foundation Vientiane, Lao PDR 26 July 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................... i Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................... iii 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Background .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Laos Legal Aid Support Program................................................................................................... 1 1.2 This Report ........................................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Methodology and Coverage ................................................................................................................ 2 1.4 Limitations ........................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Contextual Analysis ........................................................................................................................3 2.1 Gender Equality .................................................................................................................................. -

Balancing the Returns to Catchment Management: the Economic Value of Conserving Natural Forests in Sekong, Lao PDR

Balancing the Returns to Catchment Management: The Economic Value of Conserving Natural Forests in Sekong, Lao PDR Rina Maria P. Rosales, Mikkel F. Kallesoe, Pauline Gerrard, Phokhin Muangchanh, Sombounmy Phomtavong & Somphao Khamsomphou IUCN Water, Nature and Economics Technical Paper No. 5 4 Water and Nature Initiative This document was produced under the project "Integrating Wetland Economic Values into River Basin Management", carried out with financial support from DFID, the UK Department for International Development, as part of the Water and Nature Initiative of IUCN - The World Conservation Union. The designation of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of materials therein, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or DFID concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication also do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, or DFID. Published by: IUCN — The World Conservation Union Copyright: © 2005, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior permission from the copyright holder, providing the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of the publication for resale or for other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. Citation: R. Rosales, M. Kallesoe, P. Gerrard, P. Muangchanh, S. Phomtavong and S. Khamsomphou, 2005, Balancing the Returns to Catchment Management: The Economic Value of Conserving Natural Forests in Sekong, Lao PDR. IUCN Water, Nature and Economics Technical Paper No. -

2018 Transport Costs and Prices in Lao

Transport Costs and Prices in Lao PDR Unlocking the Potential of an Idle Fleet 2018 Transport Costs and Prices in Lao PDR Unlocking the Potential of an Idle Fleet Transport Costs and Prices in Lao PDR: Unlocking the Potential of an Idle Fleet Final report September 2018 Report No: AUS0000443 iii Table of Contents Table of Contents Acknowledgements vi Acronyms and Abbreviations vii Exchange rates vii Executive Summary 1 1 Background 4 2 Scope and methodology 6 Scope 6 Methodology 6 Limitations 8 3 Findings and Results 10 Transport market 10 Vehicle utilization in comparison 16 Contracts and price setting 34 4 Policy options and regional trade 36 Annex I Technical notes on the variables used in the models 40 Annex II Axle load limits in Lao PDR 44 References 45 iv Transport Costs and Prices in Lao PDR Unlocking the Potential of an Idle Fleet List of Boxes Box 1 Common trucks used in Lao PDR 13 Box 2 Using bus services for freight transportation 14 Box 3 Comparing transport costs with the findings of other studies 21 Box 4 Overstated profits 31 Box 5 The transshipment model 38 List of Figures Figure 1 Topographical map of Lao PDR 15 Figure 2 Average truck mileage in selected developing countries in 2007 17 Figure 3 Total cost per ton-km by cargo carried per wheel per year (all observations) 17 Figure 4 Breakdown of variable costs 19 Figure 5 Variable and total costs for selected routes (LAK per ton-km) 20 Figure 6 Operating costs (LAK per ton-km) by vehicle size 25 Figure 7 Variable costs (LAK per ton-km) by vehicle size and route direction 25 Figure 8 Volume vs. -

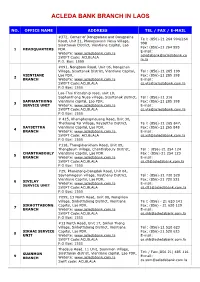

Acleda Bank Branch in Laos

ACLEDA BANK BRANCH IN LAOS NO. OFFICE NAME ADDRESS TEL / FAX / E-MAIL #372, Corner of Dongpalane and Dongpaina Te l: (856)-21 264 994/264 Road, Unit 21, Phonesavanh Neua Village, 998 Sisattanak District, Vientiane Capital, Lao Fax: (856)-21 264 995 1 HEADQUARTERS PDR. E-mail: Website: www.acledabank.com.la [email protected] SWIFT Code: ACLBLALA m.la P.O. Box: 1555 #091, Nongborn Road, Unit 06, Nongchan Village, Sisattanak District, Vientiane Capital, Tel : (856)-21 285 199 VIENTIANE Lao PDR. Fax: (856)-21 285 198 2 BRANCH Website: www.acledabank.com.la E-mail: SWIFT Code:ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 Lao-Thai friendship road, unit 10, Saphanthong Nuea village, Sisattanak district, Tel : (856)-21 316 SAPHANTHONG Vientiane capital, Lao PDR. Fax: (856)-21 285 198 3 SERVICE UNIT Website: www.acledabank.com.la E-mail: SWIFT Code:ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 # 415, Khamphengmeuang Road, Unit 30, Thatluang Tai Village, Xaysettha District, Te l: (856)-21 265 847, XAYSETTHA Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR. Fax: (856)-21 265 848 4 BRANCH Website: www.acledabank.com.la, E-mail: SWIFT Code: ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 #118, Thongkhankham Road, Unit 09, Thongtoum Village, Chanthabouly District, Tel : (856)-21 254 124 CHANTHABOULY Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR Fax : (856)-21 254 123 5 BRANCH Website: www.acledabank.com.la E-mail: SWIFT Code:ACLBLALA [email protected] P.O Box: 1555 #29, Phonetong-Dongdok Road, Unit 04, Saynamngeun village, Xaythany District, Tel : (856)-21 720 520 Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR. -

Rra Report Attapeu Watershed Attapeu

Page 1 of 9 ADB RETA 5771 Poverty Reduction & Environmental Management in Remote Greater Mekong Subregion Watersheds Project (Phase I) RRA REPORT ATTAPEU WATERSHED ATTAPEU & CHAMPASSACK PROVINCE, LAO PDR Special Report By Latsamay Sylavong 1. General Background Attapeu watershed is located in the Southern part of Lao PDR. This watershed is covered in 2 provinces as the whole of Attapeu province and a small part of Champassack provinces (the Plateau Boloven). There are about 900 Kilometres from Vientiane Municipality and 180 kilometres from Pakse. Access to those 4 villages differs from one to another village due to the selection criteria for the RRA survey in order to cover the main ethnic minorities in the watershed area. It is found easy access to 2 villages of Champassack province (Boloven Plateau) for both seasons and very difficult to get to other 2 villages of Attapeu province, especially during raining season. The purpose of this survey is to describe the existing agroecosystems within the watershed area as the relationship to the use of forest resource by human population. In addition, Attapeu watershed is one of the shortlist watersheds priorities in Lao PDR. In the Attapeu watershed 4 villages were studied and detailed information of demographic survey in different ethnic villages as Nha Heune, Alak, Laven and Chung. The number of villages depends on the time available for this survey and the difficulty in access within this area, and the time spending at each village also depends on the size of the village. All 4 villages were selected by the survey team together with the local authorities of both provinces as Champassack and Attapeu. -

8Th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO- ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN

Lao People’s Democratic Republic Peace Independence Unity Prosperity 8th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO- ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2016–2020) (Officially approved at the VIIIth National Assembly’s Inaugural Session, 20–23 April 2016, Vientiane) Ministry of Planning and Investment June 2016 8th FIVE-YEAR NATIONAL SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2016–2020) (Officially approved at the VIIIth National Assembly’s Inaugural Session, 20–23 April 2016, Vientiane) Ministry of Planning and Investment June 2016 FOREWORD The 8th Five-Year National Socio-economic Development Plan (2016–2020) “8th NSEDP” is a mean to implement the resolutions of the 10th Party Conference that also emphasizes the areas from the previous plan implementation that still need to be achieved. The Plan also reflects the Socio-economic Development Strategy until 2025 and Vision 2030 with an aim to build a new foundation for graduating from LDC status by 2020 to become an upper-middle-income country by 2030. Therefore, the 8th NSEDP is an important tool central to the assurance of the national defence and development of the party’s new directions. Furthermore, the 8th NSEDP is a result of the Government’s breakthrough in mindset. It is an outcome- based plan that resulted from close research and, thus, it is constructed with the clear development outcomes and outputs corresponding to the sector and provincial development plans that should be able to ensure harmonization in the Plan performance within provided sources of funding, including a government budget, grants and loans, -

Laos Tax Profile

Laos Tax Profile Produced in conjunction with the KPMG Asia Pacific Tax Centre Updated: May 2016 Contents 1 Corporate Income Tax 1 2 Income Tax Treaties for the Avoidance of Double Taxation 5 3 Indirect Tax 6 4 Personal Taxation 7 5 Other Taxes 9 6 Free Trade Agreements 10 7 Tax Authority 11 © 2016 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated. All rights reserved 1 Corporate Income Tax Corporate income tax Profit tax Small and medium enterprises that are not registered under the Value Added Tax (VAT) system are subject to lump-sum tax instead of profit tax. This applies to enterprises which have annual revenue of less than LAK12 million. Tax rate A 24 percent profit tax rate applies to both domestic and foreign businesses, except for companies registered in the Lao Stock Exchange, which benefit from a five percent reduction of the normal rate for a period of four years from the date of registration in the Stock Exchange. After this period, the normal profit tax rate applies. A 26 percent profit tax rate applies to companies whose business is to produce, import, and supply tobacco products. Two percent of the tax paid by tobacco companies shall contribute to the Cigarette Control Fund (Article 46 of the Law on Tobacco Control). Small and medium enterprises that are not registered under the VAT system pay lump-sum tax at progressive rates between three percent and seven percent, depending on the nature of the business and its revenue. -

Mapping Context of Land Use for a Non-Traditional Agricultural Export

Land grabbing, conflict and agrarian‐environmental transformations: perspectives from East and Southeast Asia An international academic conference 5‐6 June 2015, Chiang Mai University Conference Paper No. 75 Mapping context of land use for a non-traditional agricultural export (NTAE) product: case study of land use for coffee plantation in Pakxong district, Champasak province, Lao PDR Saithong Phommavong, Kiengkai Ounmany and Keophouthone Hathalong June 2015 BICAS www.plaas.org.za/bicas www.iss.nl/bicas In collaboration with: Demeter (Droits et Egalite pour une Meilleure Economie de la Terre), Geneva Graduate Institute University of Amsterdam WOTRO/AISSR Project on Land Investments (Indonesia/Philippines) Université de Montréal – REINVENTERRA (Asia) Project Mekong Research Group, University of Sydney (AMRC) University of Wisconsin-Madison With funding support from: Mapping context of land use for a non‐traditional agricultural export (NTAE) product: case study of land use for coffee plantation in Pakxong district, Champasak province, Lao PDR by Saithong Phommavong, Kiengkai Ounmany and Keophouthone Hathalong Published by: BRICS Initiatives for Critical Agrarian Studies (BICAS) Email: [email protected] Websites: www.plaas.org.za/bicas | www.iss.nl/bicas MOSAIC Research Project Website: www.iss.nl/mosaic Land Deal Politics Initiative (LDPI) Email: [email protected] Website: www.iss.nl/ldpi RCSD Chiang Mai University Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University Chiang Mai 50200 THAILAND Tel. 6653943595/6 | Fax. 6653893279 Email : [email protected] | Website : http://rcsd.soc.cmu.ac.th Transnational Institute PO Box 14656, 1001 LD Amsterdam, The Netherlands Tel: +31 20 662 66 08 | Fax: +31 20 675 71 76 Email: [email protected] | Website: www.tni.org June 2015 Published with financial support from Ford Foundation, Transnational Institute, NWO and DFID. -

Laos Tax Profile

Laos Tax Profile Produced in conjunction with the KPMG Asia Pacific Tax Centre August 2018 Table of Contents 1 Corporate Income Tax 3 1.1 General Information 3 1.2 Determination of taxable income and deductible expenses 6 1.2.1 Income 6 1.2.2 Expenses 6 1.3 Tax Compliance 8 1.4 Financial Statements/Accounting 10 1.5 Incentives 12 1.6 International Taxation 13 2 Transfer Pricing 16 3 Indirect Tax 16 4 Personal Taxation 18 5 Other Taxes 20 6 Trade & Customs 21 6.1 Customs 21 6.2 Free Trade Agreements (FTA) 21 7 Tax Authority 22 1 Corporate Income Tax 1.1 General Information Tax Rate Profit tax is levied on income. Small and medium enterprises that are not registered under the Value Added Tax (VAT) system are subject to lump-sum tax instead of profit tax. This applies to enterprises which have annual revenue of less than LAK 12 million. A 24% profit tax rate applies to both domestic and foreign businesses, except for companies registered on the Lao Stock Exchange, which benefit from a 5% reduction of the normal rate for a period of 4 years from the date of registration on the Stock Exchange. After this period, the normal profit tax rate applies. A 26% profit tax rate applies to companies whose business is to produce, import, and supply tobacco products. 2% of the tax paid by tobacco companies shall be contributed to the Cigarette Control Fund (Article 46 of the Law on Tobacco Control). Small and medium enterprises that are not registered under the VAT system pay lump-sum tax at progressive rates between 3%-7%, depending on the nature of the business and its revenue. -

Doing Business in Lao PDR: 2014 Country Commercial Guide for US

Doing Business in Lao PDR: 2014 Country Commercial Guide for U.S. Companies INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT, U.S. & FOREIGN COMMERCIAL SERVICE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE, 2010. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED STATES. • Chapter 1: Doing Business In Lao PDR • Chapter 2: Political and Economic Environment • Chapter 3: Selling U.S. Products and Services • Chapter 4: Leading Sectors for U.S. Export and Investment • Chapter 5: Trade Regulations, Customs and Standards • Chapter 6: Investment Climate • Chapter 7: Trade and Project Financing • Chapter 8: Business Travel • Chapter 9: Contacts, Market Research and Trade Events • Chapter 10: Guide to Our Services Return to table of contents Chapter 1: Doing Business in Lao PDR • Market Overview • Market Challenges • Market Opportunities • Market Entry Strategy • Market Fact Sheet link Market Overview Return to top • The Lao market economy has grown at a nearly 7% clip for the last decade and is heading into a new phase of regional and global integration. After acceding to the World Trade Organization in 2013, Laos looks to the ASEAN Economic Community as a marker for its next set of economic policy and trade development goals. • The Lao government suffered through a fiscal and monetary crisis in 2013 and into 2014, brought about by poor budgetary processes, uncontrolled investment in infrastructure, and a large raise for civil servants. Government fiscal and budgetary policy formulation and implementation remain weak but the government is taking steps to address some deficiencies. • Laos is one of five remaining communist countries in the world and this legacy continues to weigh on both governance and the economy.