Land Covenants in Auckland and Their Effect on Urban Development Craig Fredrickson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of Howick Local Board

Howick Local Board OPEN MINUTES Minutes of a meeting of the Howick Local Board held in the Howick Local Board Meeting Room, Pakuranga Library Complex, 7 Aylesbury Street, Pakuranga on Monday, 16 August 2021 at 6.00pm. PRESENT Chairperson Adele White Deputy Chairperson John Spiller Members Katrina Bungard David Collings Bruce Kendall Mike Turinsky Bob Wichman Peter Young, JP ABSENT Member Bo Burns With apology Howick Local Board 16 August 2021 1 Welcome The Chair opened the meeting and welcomed those present. 2 Apologies Resolution number HW/2021/119 MOVED by Member B Wichman, seconded by Deputy Chairperson J Spiller: That the Howick Local Board: a) accept the apology from Member B Burns for absence. CARRIED 3 Declaration of Interest There were no declarations of interest. 4 Confirmation of Minutes Resolution number HW/2021/120 MOVED by Chairperson A White, seconded by Member B Wichman: That the Howick Local Board: a) confirm the ordinary minutes of its meeting, held on Monday, 19 July 2021, as a true and correct record. CARRIED 5 Leave of Absence There were no leaves of absence. 6 Acknowledgements The Chair acknowledged the Howick Youth Council and read the following acknowledgement: I wish to acknowledge the ongoing success of the Howick Youth Council as they celebrate their ten year anniversary. These multi-talented young people work on a voluntary basis, to bring together, mentor, inform and support the youth of the Howick ward whilst growing themselves to be confident and capable leaders. I congratulate Howick Youth Council – past and present. We know our community will be in great hands in the years to come. -

Auckland Progress Results

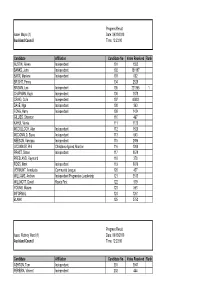

Progress Result Issue: Mayor (1) Date: 09/10/2010 Auckland Council Time: 12:23:00 Candidate Affiliation Candidate No Votes Received Rank AUSTIN, Aileen Independent 101 1552 BANKS, John Independent 102 161167 BARR, Marlene Independent 103 692 BRIGHT, Penny 104 2529 BROWN, Len Independent 105 2213651 CHAPMAN, Hugh Independent 106 1878 CRAIG, Colin Independent 107 40483 DAVE, Nga Independent 108 840 FONG, Harry Independent 109 1434 GILLIES, Shannon 110 467 KAHUI, Vinnie 111 1120 MCCULLOCH, Alan Independent 112 1520 MCDONALD, Steve Independent 113 643 NEESON, Vanessa Independent 115 2885 O'CONNOR, Phil Christians Against Abortion 116 1209 PRAST, Simon Independent 117 3578 PRESLAND, Raymond 118 278 ROSS, Mark Independent 119 3076 VERMUNT, Annalucia Communist League 120 427 WILLIAMS, Andrew Independent Progressive Leadership 121 3813 WILLMOTT, David Roads First 122 519 YOUNG, Wayne 123 553 INFORMAL 124 1261 BLANK 125 3752 Progress Result Issue: Rodney Ward (1) Date: 09/10/2010 Auckland Council Time: 12:23:00 Candidate Affiliation Candidate No Votes Received Rank ASHTON, Tom Independent 201 3941 PEREIRA, Vincent Independent 202 444 ROSE, Christine 203 5553 WEBSTER, Penny Independent 204 8063 1 INFORMAL 205 21 BLANK 206 701 Progress Result Issue: Albany Ward (2) Date: 09/10/2010 Auckland Council Time: 12:23:00 Candidate Affiliation Candidate No Votes Received Rank BALOUCH, Uzra Independent 221 736 BELL, Rodney Independent 222 3151 BRADLEY, Ian Independent 223 5273 CONDER, Laurie Independent 224 1419 COOPER, David Independent 225 2821 COOPER, -

New Network for East Auckland Consultation and Decisions Report

New Network for East Auckland Consultation and Decisions Report Contents 1. Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 2. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Background and Strategic Context ................................................................................................. 3 4. The Decision-Making Process ......................................................................................................... 4 5. Consultation Overview ..................................................................................................................... 5 5.1 Pre-Consultation ......................................................................................................................... 5 5.2 Consultation Period .................................................................................................................... 5 5.3 Post-Consultation Activity ......................................................................................................... 6 6. Public Engagement .......................................................................................................................... 6 6.1 Stakeholder Engagement ........................................................................................................... 6 6.2 Consultation Brochure .............................................................................................................. -

Howick Ethnic Affairs Consultative Committee Application Form

POSITION DESCRIPTION FOR MEMBERS OF THE HOWICK ETHNIC CONSULTATIVE COMMITTEE This document outlines: the background to the proposed Howick Ethnic Consultative Committee the expected role and responsibilities of committee members the skills and community relationships expected of committee members the nomination and selection process 1. Background The Howick Ward includes Botany, East Tamaki, Flat Bush, Howick and Pakuranga. Our area is home to one of the highest proportion of migrants in the Auckland Region with 48% of our residents born overseas and just under half this group, 22%, relatively recent migrants having settled in New Zealand in the last 10 years. (Census 2006 data). Our migrant community is very diverse. In addition to settlers from European countries Howick is home to large numbers of people from China, India and Korea and smaller numbers from the Pacific Islands, other east, south east and south Asian countries, the Middle East, Africa and Latin America. The Howick Local Board wants to create strong, connected, flourishing communities where everyone feels welcome and able to participate. The Board recognises the challenges faced by new settlers, in particular those: for whom English is a second language, and who come from cultures very different from New Zealand, and who lack strong support systems here In response the Board has established the Ethnic Affairs Portfolio to be responsible for developing relationships with the many ethnic communities in Howick. The Board has set two key objectives for its Ethnic Affairs Portfolio: 1. In Howick we want to ensure that different peoples and cultures are respected, celebrated and woven together to create a strong and unique identity. -

Open 1 Business Report August 2021

Board Meeting | 26 August 2021 Open Session Business Report – August 2021 This business report summarises activities undertaken in this reporting period by Auckland Transport (AT) which contribute to the six outcome areas of the Auckland Plan. The six outcome areas of the Auckland Plan are: Auckland Plan Description Outcome Focussed on Aucklanders being able to contribute to their city and its direction for the future. It aims to improve Belonging and accessibility to the resources and opportunities that Aucklanders need to grow and reach their full potential and is about participation working towards an inclusive and equitable region, focused on improving the health and wellbeing of all Aucklanders. This outcome also covers wellbeing and health, a thriving and prosperous Auckland is a safe and healthy Auckland. Māori identity and Seeks to advance Māori wellbeing at all levels from whānau, hapū and iwi and across all areas of life: housing, wellbeing employment, education and health. Homes and places Focussed on accessibility to healthy and affordable homes as well as inclusive public places. Transport and Providing easy, safe and sustainable transport modes across an integrated network, in alignment with the Auckland access Transport Alignment Project (ATAP). Environment and Preserving and protecting the natural environment and significant land marks and cultural heritage unique to Auckland. cultural heritage Opportunity and Ensuring adaptability in the face of a rapidly changing economy and taking advantage of technological developments prosperity through collaboration and participation. Recommendation That the Chief Executive’s report be received. Prepared by: Shane Ellison, Chief Executive Page 1 of 25 Board Meeting | 26 August 2021 Open Session Belonging and participation For AT, this outcome area is focussed on improving accessibility, inclusivity and the well-being and safety of Aucklanders. -

Annexure a to Procedural Minute 6

Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan Appendix 3.1 Schedule for the Outstanding Natural Features Overlay Owner/ Approral/ Sub#/ Point Name Theme Topic Subtopic Summary Submission Type Support Evidence Comentary Investigate 81 Mt Royal Rd, Mt Albert, and all other lava cave Appendix 3.1 - Schedule for the entrances, for inclusion in the SEA schedule [Note - relates to Outstanding Natural Outstanding Natural Features ONFs. Refer to Albert-Eden Local Board Views, Volume 26, page 5716-3481 Auckland Council Features (ONF) Rules Overlay Add 30/103]. Local Government no iv Investigate the 'Spring', located under Crystal Motors at 11 Ruru Appendix 3.1 - Schedule for the St, Eden Terrace, for inclusion in the SEA schedule [Note - Outstanding Natural Outstanding Natural Features relates to ONFs. Refer to Albert-Eden Local Board Views, Volume 5716-3482 Auckland Council Features (ONF) Rules Overlay Add 26, page 30/103]. Local Government no iv Auckland Volcanic Appendix 3.1 - Schedule for the Include volcanic features in former outlying district such as Cones Society Outstanding Natural Outstanding Natural Features Franklin within the PAUP including Pukekohe Hill, Puni Mountain, 4485-11 Incorporated Features (ONF) Rules Overlay Add Pukekohe East crater. Key Stakeholder no iv Auckland Volcanic Appendix 3.1 - Schedule for the Cones Society Outstanding Natural Outstanding Natural Features Include Pukekohe Hill and Puni Mountain as outstanding natural 4485-13 Incorporated Features (ONF) Rules Overlay Add features. Key Stakeholder no iv Auckland Volcanic Appendix 3.1 - Schedule for the Cones Society Outstanding Natural Outstanding Natural Features Apply V1 and V2 overlays to volcanic reserves and surrounding 4485-21 Incorporated Features (ONF) Rules Overlay Add Includeareas. -

Auckland Council ALUPIS Mario

ID Council Issue Last Name First Names Affiliation 3764 AC Mayor - Auckland Council ALUPIS Mario <none> 1537 AC Mayor - Auckland Council AUSTIN Aileen Independent 6141 AC Mayor - Auckland Council BRIGHT Penny Independent 6156 AC Mayor - Auckland Council BROWN Patrick Communist League 1385 AC Mayor - Auckland Council CHEEL Tricia STOP 211 AC Mayor - Auckland Council CRONE Vic Independent 2597 AC Mayor - Auckland Council GOFF Phil Independent 420 AC Mayor - Auckland Council HAY David Independent 6131 AC Mayor - Auckland Council HENETI Alezix <none> 663 AC Mayor - Auckland Council HOLLAND Adam John Auckland Legalise Cannabis 1416 AC Mayor - Auckland Council MARTIN Stan Independent 6181 AC Mayor - Auckland Council NGUYEN Binh Thanh Independent 703 AC Mayor - Auckland Council O'CONNOR Phil Christians Against Abortion 1622 AC Mayor - Auckland Council PALINO John Independent 398 AC Mayor - Auckland Council SWARBRICK Chloe Independent 1370 AC Mayor - Auckland Council THOMAS Mark Independent 1239 AC Mayor - Auckland Council YOUNG Wayne <none> 1618 AC Albany Ward BENSCH John Independent 6130 AC Albany Ward HENETI Alezix <none> 6214 AC Albany Ward LOWE Graham Auckland Future 1389 AC Albany Ward WALKER Wayne Putting People First 688 AC Albany Ward WATSON John Putting People First 6213 AC Albany Ward WHYTE Lisa Auckland Future 1629 AC Albert-Eden-Roskill Ward CASEY Cathy City Vision 432 AC Albert-Eden-Roskill Ward FLETCHER Christine C&R - Communities & Residents 1433 AC Albert-Eden-Roskill Ward HARRIS Rob Auckland Future 2579 AC Albert-Eden-Roskill -

Local Board Information and Agreements Draft Long-Term Plan 2012-2022

DRAFT LONG-TERM PLAN 2012-2022_ VOLUME FOUR LOCAL BOARD INFORMATION AND AGREEMENTS DRAFT LONG-TERM PLAN 2012-2022_ VOLUME FOUR LOCAL BOARD INFORMATION AND AGREEMENTS About this volume About this volume This is Volume Four of the four volumes that make up the draft LTP. It is set out in two parts, one which provides background on the role of local boards, their decision-making responsibilities and some general information about local board plans and physical boundaries. The second part contains the individual local board agreements for all 21 local boards, which contain detailed information about local activities, services, projects and programmes and the corresponding budgets for the period 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2013. Here we have also included additional information like ten-year budgets for each board and a capital projects list. What this volume covers: the status of draft local board agreements how to have your say during the public consultation period an overview of the local boards local board activities information on the development of local board plans and agreements local board financial information including a consolidated statement of expenditure on local activities about each local board, with an overview of the local board including their strategic priorities and a message from the chairperson draft local board agreements for each local board covering scope of activities levels of service and performance measures local activities including key initiatives and projects expenditure and funding notes to the local board agreements contact details, how to contact your local board, including individual contact details for each local board member an appendix to each Local Board information section which includes their expenditure statements and capital projects for the ten-year period 2012 to 2022. -

2019 Local Elections Preliminary Results – Mayor, Local Board

Result: LGE 2019 - Preliminary Result Type: Preliminary Candidates sorted by: Votes Generated on: Sunday 13 October 2019 Elections: Auckland Council Election: 01 - Auckland Council Issue: Mayor - Auckland Council Number of vacancies: 1 Candidate Voting ID Candidate Name Affiliation Votes Received Rank 105 GOFF, Phil Independent 176599 1 118 TAMIHERE, John JT for Mayor.co.nz 79551 111 LORD, Craig Independent 29032 108 HONG, John Independent 15965 109 JOHNSTON, Ted 15401 119 VAUGHAN, Peter 6127 102 COOTE, Michael Independent 5530 101 CHEEL, Tricia STOP Trashing Our Planet 4013 114 O'CONNOR, Phil Christians Against Abortion 3917 110 KRUGER, Susanna Justice for Families 2840 104 FORDE, Genevieve 2824 115 SAINSBURY, Tom Independent 2804 116 SNELGAR, Glen Old Skool 2576 117 STOPFORD, Tadhg Tim The Hemp Foundation 2380 107 HENRY, Jannaha 2356 103 FEIST, David John LiftNZ 2259 112 MADDERN, Brendan Bruce Independent 1430 121 YOUNG, Wayne Virtual Homeless Community 1388 120 VERMUNT, Annalucia Communist League 1030 113 NGUYEN, Thanh Binh Independent 941 106 HENETI, Alezix 507 122 Informal 1558 123 Blank 6982 Election: 01 - Auckland Council Issue: Albany Ward Number of vacancies: 2 Candidate Voting ID Candidate Name Affiliation Votes Received Rank 224 WATSON, John Putting People First 28073 1 223 WALKER, Wayne Putting People First 24371 2 222 PARFITT, Julia Independent 19884 221 HENETI, Alezix 3167 225 Informal 23 226 Blank 2989 Election: 01 - Auckland Council Issue: Albert-Eden-Puketāpapa Ward Number of vacancies: 2 Candidate Voting ID Candidate -

Written Submissions Written Submissions

ATTACHMENT 3 ATTACHMENTWRITTEN 3 - WRITTEN SUBMISSIONS SUBMISSIONS WRITTEN SUBMISSIONS Individuals Submissions Contents Page Sub# Individual Page 4 Dr Adriana Gunder QSM JP 2 6 Dr Grant Gillon 2-3 7 Kevin Fox 3-4 3 Nick Muir 4 6 Owen Thompson 4-5 *Submission number relates to the order the submission was received and used here for cross reference purposes. 1 Sub# Individual Submission 4 Dr Adriana Gunder QSM JP I agree with option 4 but I would like no signs at all on private land on specific public places as per the list you propose. 1. My comments are that because they are on private land there is no uniformity and it look very messy, plus the sign of one party (council election or political election) can upset neighbors and they might be cause for vandals to came into a private property to damage the sign. We can see damage of the signs into public land and it is no different if they are on private property. 2. In some European countries when there is an election (council or general) the council provide some large board in very public places and a part of the board is given to every political parties and they can put on it what they want, but no in other places. 6 Dr Grant Gillon 1. I question the right of Auckland Transport to promulgate such a bylaw. I don‟t question the right of Auckland Transport to promulgate bylaws within its jurisdiction but argue that Election matters are not matters for Auckland Transport. -

UXBRIDGE COMMUNITY PROJECTS INCORPORATED NOMINATIONS for BOARD MEMBERS for 2019 / 2020 Angela Campbell Cliff Halsey (Current

UXBRIDGE COMMUNITY PROJECTS INCORPORATED NOMINATIONS FOR BOARD MEMBERS FOR 2019 / 2020 Angela Campbell Having grown up in Howick, I (like many) first visited Uxbridge as a school child. I’ve since taken classes, attended events and volunteered at the new centre, and I appreciate the part that UXBRIDGE plays in fostering an engaged, diverse arts community in the Howick Ward. Previously having volunteered with numerous not-for-profit organisations (including the Cancer Society, PCOS Foundation and Howick Hornets Rugby League Football Club) I bring with me a working knowledge of professional fundraising and engagement, a ‘hands on’ approach, and a focus on youth, sustainability and inclusion. Cliff Halsey (current Deputy Chair) I have lived in Howick for 40 years, widowed now with 2 adult children and 6 grandchildren. I have served locally many years in voluntary positions including Owairoa Primary PTA, Howick Squash, Pakuranga Golf Club, Auckland Golf Association and Howick Community Board. I have been involved at UXBRIDGE for 11 years serving as Deputy Chair and now Chair. We have been in our grand new premises for nearly 2 years now and are still dealing with various teething issues. We are currently processing a number of items with the Howick Local Board and Auckland Council and having established a good working relationship with them I am keen to see these issues finalised. Jan Hollway (current Chair) I’ve lived in Howick for 16 years, though my working life has been all over NZ, mainly in running a private training business. I’ve been a director for many years, both in business and the community, and am a Chartered Member of Institute of Directors. -

Howick Local Economic Overview 2019

20 MARCH 20 AUCKLAND ECONOMIC OVERVIEWS HOWICK ── LOCAL BOARD ECONOMIC OVERVIEW aucklandnz.com/business a 2 | Howick Local Economic Overview 2019 2 | Document Title – even page header Contents 1 Introduction 2 People and Households 3 Skills 4 Local Economy 5 Employment Zones 6 Development trends 7 Economic Development Opportunities 8 Glossary aucklandnz.com/business 3 3 | Document Title – even page header Introduction What is local economic development ATEED’s goal is to support the creation of quality jobs for all Aucklanders and while Auckland’s economy has grown in recent years, the benefits of that growth are not distributed evenly. Local economic development brings together a range of players to build up the economic capacity of a local area and improve its economic future and quality of life for individuals, families and communities. Auckland’s economic development Auckland has a diverse economy. While central Auckland is dominated by financial, insurance and other professional services, parts of south and west Auckland have strengths in a range of manufacturing industries. In other areas, tourism is a key driver and provides a lot of local employment while there are also areas that are primarily residential where residents commute to the city centre or one of the industrial precincts for employment. The Auckland region also has a significant primary sector in the large rural areas to the north and south of the region. The Auckland Growth Monitor1 and Auckland Index2 tell the story behind Auckland’s recent economic growth. While annual GDP growth of 4.3 per cent per year over the last five years is encouraging, we want our economy to be more heavily weighted towards industries that create better quality jobs and generate export earnings.